Implications for the Environment, China's Smallholder Farmers And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antiques & Collectors

Antiques & Collectors Tuesday 28 June 2011 10:00 Gildings 64 Roman Way Market Harborough Leicestershire LE16 7PQ Gildings (Antiques & Collectors) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 German" box iron (3)." The Norwood Goffering Machine, labelled - T. Bradford & Co. Estimate: £0.00 - £0.00 London & Manchester"." Estimate: £0.00 - £0.00 Lot: 13 Jobson 00 flat iron and a collection of other 00 and small size Lot: 2 flat irons, (16). Victorian rosewood press, with a petit point needle work panel. Estimate: £0.00 - £0.00 Estimate: £0.00 - £0.00 Lot: 14 Lot: 3 Stained pine display cabinet, the drawers fitted with vintage hair Cast iron silk leaf mould, wooden handle, brass stand, three and beauty items, many in original packaging. others with brass stands and others without stands. Estimate: £0.00 - £0.00 Estimate: £0.00 - £0.00 Lot: 15 Lot: 4 Continental carved hardwood bat-shaped laundry board, A No. 2 GEM model mangle, marked - American Wringer probably 18th century. Company New York" and two other small mangles (3)." Estimate: £0.00 - £0.00 Estimate: £0.00 - £0.00 Lot: 16 Lot: 5 Continental hardwood bat-shaped laundry board, probably 19th Crown cast iron crimping machine, the platform with registration century. mark for 1880. Estimate: £0.00 - £0.00 Estimate: £0.00 - £0.00 Lot: 17 Lot: 6 Continental carved wood bat-shaped laundry board. Cast iron rocking trivet, supporting two French type" irons cast Estimate: £0.00 - £0.00 decoration." Estimate: £0.00 - £0.00 Lot: 18 Cast brass cinquefoil rosette silk flower mould with stand, Lot: 7 another, smaller and two cast brass block-shaped moulds, (4). -

Southern Planter: Devoted to Practical and Progressive Agriculture

: : : : Established 1840. THE Sixty-Fourth Year. Southern Planter A MONTHLY JOURNAL DEVOTED TO Practical and Progressive Agriculture, Horticulture, Trucking, Live Stock and the Fireside. OFFICE: 28 NORTH NINTH STREET, RICHMOND, VIRGINIA. THE SOUTHERN PLANTER PUBLISHING COMPANY, Proprietors. J. F. JACKSON, Editor sad General Manager. Vol. 64. MARCH, 1903. No. 3. CONTENTS. FARM MANAGEMENT LIVE STOCK AND DAIRY : Editorial— for the 153 Work Month Herefords at Anneneld, Clarke Co., Va 177 "All Flesh is Grass." 156 HerefordB'at Castalia, Albemarle Co., Va 177 High Culture or the Intensive System, as Applied Confining CowsiContinuously During Winter. 178 to the Culture of Corn. ...^ 157 A Green Crop All Summer—Corn and Cow-Peas.. 159 Bacon, and a " Bacon Breed." - 179 Grasses and Live Stock Husbandry—Bermuda Biltmore Berkshire Sale « ~ 180 160 GraBS The Brood Sow 181 The Difference in Resalts from Using a Balanced and an Unbalanced Fertilizer 161 Artichokes ^--•"MtABD: My Experience with SO 2, gif x Italian Grass Rye -«-JL ** ,. \aying Competition of Breeds 182 Improving Mountain! Land 163 Nitrate of Soda as.a Fertilizer for Tobacco Plant- Cost cf Producing a Broiler 182 Beds '. 164 Humus ~ 164 THE HORSE Enquirer's Column (Detail {Index, page 185)....'.... 166 Notes 183 TRUCKING, GARDEN 'ANDIORCHARD Editorial—Work for the Month 171 Notes on Varieties of Apples at the Agricultural MISCELLANEOUS Experiment Station, Blacksburg, Va „ 174 Brownlow's Good Roads Bill—A Practical and Garden and Orchard Notes _ 175 Conservative Measure „ 184 Work in the Strawberry.Patch 176 Editorial—Spraying Fruit Trees and Vegetable Publisher's Notes - 185 Crops 176 Editorial—San Jose Scale ~. -

What the Pig Ate: a Microbotanical Study of Pig Dental Calculus from 10Th–3Rd Millennium BC Northern Mesopotamia

JASREP-00256; No of Pages 9 Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports xxx (2015) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep What the pig ate: A microbotanical study of pig dental calculus from 10th–3rd millennium BC northern Mesopotamia Sadie Weber ⁎, Max D. Price Harvard University, Department of Anthropology, 11 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138, United States article info abstract Article history: One of the main questions that zooarcheologists have attempted to answer in their studies of ancient Received 15 February 2015 agropastoral economies relates to animal diet. Starch granules and phytoliths, which derive from the plant Received in revised form 3 November 2015 foods consumed over the course of an animal's life, become imbedded in dental calculus and thus offer direct Accepted 12 November 2015 clues about diet. In this paper, we investigate pig diet with an eye toward understanding husbandry strategies Available online xxxx in northern Mesopotamia, the region in which pigs were first domesticated, from the Epipaleolithic though the Keywords: Early Bronze Age. Our data reveal that pigs consumed an assortment of plant foods, including grasses, wild tubers, fi Microbotanical analysis acorns, and domestic cereals. Although poor preservation plagued the identi cation of plant microremains at Dental calculus Epipaleolithic (10th millennium cal. BC) Hallan Çemi, the identification of a diet based on tubers and grasses Pig husbandry matches models of wild boar diet. Pigs at 6th millennium Domuztepe, 5th millennium Ziyadeh, and 4th millen- nium Hacinebi consumed cereals, particularly oats (Avena sp.) and barley (Hordeum sp.), as well as wild plant food resources. -

1Waste Paper Couection

S A l-U B D A T , O C T O B E R 8» I M f nui Wskthir iOatuIffBter lEttrathg lifrraUii Avwags Daily Hit < PetMaal e« S. E. WaaMmr 1 tWtteMMOM ^ ISIS Fair and eeaUnwed warm tUa Cloeka have Inspired all sorts tS poetry and many a tock has been Takes Leading Role HoUister PTA afteraeoat fair tonight; eooi$r »ntTown ticked o ff about them. 9,676 than laat jdght; Tnmday M r. Heard Along Main Street Winding the parlor clock used to VERNON SERVICENTER eeeler aleag neaat. ________; »N tlii» •< th* *p- be something of a regular - rittuU. lists Program There were two keys, one for the F orm erly **JaekU** M an ekesterr^^U y o f Village Charm Otroto win u And on Somo of Maneho$tor^$ Side StriM$, Too [ at T:48 at tha Boufh Maffa* time and one for the bell. It wasn’t ROUTE 83; VERNON _____ with Mlaa Martanna a hard job but a compelling one. Original Operetta to Be (SIX'TEEN PAGES) PRICE POUB CFNT3 ,:^iWktaga aid Mlpa Kartan Jeaae- If you didn’t wind, you didn’t dine ^ GAS OIL ACCESSORIES If severe bumps on the head In-foThe Her^d. Thwefota it was on time. VOL. LXDU NO. i - man aaTwatiwaa early childhood can result in a^ no vahie to lu .. Wa wondered that ^Presented oli Next tha “Postage Due" charge was so Probably-the biggest clock wind GENERAL REPAIRS race of mantaUy deficient adults, ing job ever to rear up la Man' Tuesday Evening ' th a B aitfw d County RapubUcaa Manchester can look forward to high seven cents being far more DOUBLE S & H GREEN STAMPS weewn'a Aaaoelation will combine than usual1 unless It { heav Chester is the one that has been ■—i.ii.iVi w H d n j o r>r Cotton' Pickers the bright prospects of harboring taken over by Policeman Winfield New with tha Mbnehaatar Rapublloan a bunch of Idiots in tha near future. -

Strategic Use of Straw at Farrowing

Strategic Use of Straw at Farrowing Effects on Behaviour, Health and Production in Sows and Piglets Rebecka Westin Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science Department of Animal Environment and Health Skara Doctoral Thesis Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Skara 2014 Acta Universitatis agriculturae Sueciae 2014:69 ISSN 1652-6880 ISBN (print version) 978-91-576-8086-0 ISBN (electronic version) 978-91-576-8087-7 © 2014 Rebecka Westin, Skara Print: SLU Service/Repro, Uppsala 2014 Strategic Use of Straw at Farrowing. Effects on Behaviour, Health and Production in Sows and Piglets Abstract According to EU-regulations, sows should be provided with suitable manipulable material, this in order to meet their behavioural needs. “Strategic use of straw at farrowing” means that loose housed sows are provided with 15-20 kg of chopped straw once at 2 days prior to the calculated date of farrowing. This gives them increased access to nesting material and creates a more suitable environment with an improved micro-climate and increased comfort during farrowing and early lactation, compared to a limited use of straw. After farrowing, the straw is left to gradually drain through the slatted floor and is then replaced by a daily supply of 0.5–1 kg straw in accordance with common Swedish management routines. The overall aim of this thesis was to evaluate if strategic use of straw at farrowing is technically feasible and to investigate its effect on behaviour, health and production in farrowing sows and suckling piglets by studying the sow’s nest-building behaviour and farrowing duration, the prevalence of bruising, piglet weight gain and pre-weaning mortality. -

Parma (Parma Ham) Protected Designation of Origin Specifications

Prosciutto di Parma (Parma Ham) Protected Designation of Origin Specifications PROSCIUTTO DI PARMA (PARMA HAM) PROTECTED DESIGNATION OF ORIGIN (Specifications and Dossier pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation EEC no. 2081/92 dated 14 July 1992) ANNEXES SECTION A REFERENCE DOCUMENTS Law No. 506 dated 04 July 1970 Law No. 26 dated 13 February 1990 Presidential Decree No. 83 dated 03 January 1978 Ministerial Decree No. 253 dated 15 February 1993 SECTION B REFERENCE DOCUMENTS Measure defining analytical qualitative parameters. Directive on the slicing and packaging of Parma Ham. Blank sample pack of pre-sliced Parma Ham. SECTION C REFERENCE DOCUMENTS Definition of processing area Definition of area of origin of raw materials Excerpt of law No. 142 dated 19 February 1992 Exemplifying digest of relevant articles: - the use of whey and grains in the diet of "heavy pigs"; - breeds that are fit and unfit for the production of "heavy pigs"; - research studies on the characteristics of subcutaneous fat in "heavy pigs" Bibliographic material on the production of Italian heavy pigs Specimen of the breeder's certificate Directive on the procedures for filling in and handling breeder's certificates Specimens of application forms for breeding farms and abattoirs Specimen of numbered abattoir firebrand ("PP") Specimens of the seal 1 Specimen of the seal application report Specimen of the certification brand (fire-branding) report Partial copy of the producer's report Imprint of the Ducal Crown trademark SECTION D REFERENCE DOCUMENTS Bibliography of publications containing historical references to various aspects of Parma Ham, in particular pig breeding in the Po Valley and in Parma, production and marketing of Parma Ham. -

Rhyming Dictionary

Merriam-Webster's Rhyming Dictionary Merriam-Webster, Incorporated Springfield, Massachusetts A GENUINE MERRIAM-WEBSTER The name Webster alone is no guarantee of excellence. It is used by a number of publishers and may serve mainly to mislead an unwary buyer. Merriam-Webster™ is the name you should look for when you consider the purchase of dictionaries or other fine reference books. It carries the reputation of a company that has been publishing since 1831 and is your assurance of quality and authority. Copyright © 2002 by Merriam-Webster, Incorporated Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Merriam-Webster's rhyming dictionary, p. cm. ISBN 0-87779-632-7 1. English language-Rhyme-Dictionaries. I. Title: Rhyming dictionary. II. Merriam-Webster, Inc. PE1519 .M47 2002 423'.l-dc21 2001052192 All rights reserved. No part of this book covered by the copyrights hereon may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems—without written permission of the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America 234RRD/H05040302 Explanatory Notes MERRIAM-WEBSTER's RHYMING DICTIONARY is a listing of words grouped according to the way they rhyme. The words are drawn from Merriam- Webster's Collegiate Dictionary. Though many uncommon words can be found here, many highly technical or obscure words have been omitted, as have words whose only meanings are vulgar or offensive. Rhyming sound Words in this book are gathered into entries on the basis of their rhyming sound. The rhyming sound is the last part of the word, from the vowel sound in the last stressed syllable to the end of the word. -

China's Pork Miracle?

Global Meat Complex: The China Series China’s Pork Miracle? Agribusiness and Development in China’s Pork Industry By: Mindi Schneider with Shefali Sharma Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy February 2014 Global Meat Complex: The China Series China’s Pork Miracle? Agribusiness and Development in China’s Pork Industry By Mindi Schneider with Shefali Sharma Published February 2014 The author is an Assistant Professor of Agrarian, Food and Environmental Studies at the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in The Hague, Netherlands. Shefali Sharma is is based in Washington DC as the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy’s (IATP) Director ofAgricultural Commodities and Globalization Program. Some of the research presented in this report was supported by Oxfam Hong Kong. The Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy works locally and globally at the intersection of policy and practice to ensure fair and sustainable food, farm and trade systems. More at iatp.org 2 INSTITUTE FOR AGRICULTURE AND TRADE POLICY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When we embarked on this project to examine China’s role in the Global Industrial Meat Complex, we had intended to produce only one report. Fairly quickly into the research, we realized—given the complexity of China, the scale and scope of production and the rapid rate at which different meat segments in China are evolving—individual sectors such as feed, pork, dairy and poultry merited their own stories. This large endeavor could not have been achieved without the help of numerous people that were involved from the conception, research, drafting. translation and editing phases of the project. First, we’d like to thank Jim Harkness, IATP’s president for 7 years (2006–2013) as the person who conceived this project as a critical contribution to the debate on the expansion of industrial meat production, its increasing concentration and its implications for social and environmental justice. -

![Congressional Record-House. 391]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9175/congressional-record-house-391-2069175.webp)

Congressional Record-House. 391]

1913. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. 391] J. B. Phillips to be postmaster at Howe, Tex., in place of KANSAS. Laban B. Ruth. Incumbent's commission expired April 13, Jefferson Dunham, Little River. 1912. • "W1.lliam A. Matteson, Abilene. R. S. Rike to be postmaster at Farmersville, Tex., in place of Edward W. Morton, deceased. KENTUCKY. Sam D. Seale to be postmaster at Floresville, Tex., in place of Mary .Alice Sweet~, Bardstown. William Reese. Incumbent's commission &pired February 11, NEW JERSEY• . 1913. W. H. Cottrell, Princeton. J. W. White to be postmaster at Uvalde, Tex., in place of Guido R. Goldbeck, resigned. OKLAHOMA. VIRGINIA. 0. H. P. Brewer, Muskogee. William C. Johnston to be postmaster at Williamsburg, Va., OREGON. in place of 'rI:Hnnas C. Peachy. Incumbent's commission. ex Frank S. Myers, Portland. pired. February 9, 1913. Johti E. Rogers to be postmaster at Strasburg, Va., in place of Asbmy Redfern. Incumbent's commission expired January • HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. 11, 1913. .Arthur W. Sinclair to be postmaster at Manassas, Va., in TmmsDAY, Ap1il S84, 1913• place of Howard P. Dodge. Incumbent's commission expired The House met at 11 o'clock a. m. January 14, 1913. The Chaplain, Rev. Henry N. Couden, D. D., offered the fol- WASHINGTON. lowing prayer : · F. A. Kennett to be postmaRter at Prosser, Wash., in place Father in heaven, so move upon our hearts that the Godlike of Thomas N. Henry. Incumbent's commission expired January may be Jn the ascendency as we pass along life's rugged way; 16, 1911. that we may leave in our wake a record of which we may justly W. -

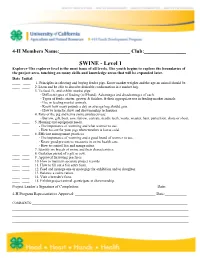

SWINE - Level 1 Explorer-The Explorer Level Is the Most Basic of All Levels

4-H Members Name:___________________________ Club:________________ SWINE - Level 1 Explorer-The explorer level is the most basic of all levels. The youth begins to explore the boundaries of the project area, touching on many skills and knowledge areas that will be expanded later. Date Initial ____ ____ 1. Principles in selecting and buying feeder pigs. Know market weights and the age an animal should be. ____ ____ 2. Learn and be able to describe desirable conformation in a market hog. ____ ____ 3. To feed, fit, and exhibit market pigs: - Different types of feeding (self-hand). Advantages and disadvantages of each. - Types of feeds: starter, grower & finisher, & their appropriate use in feeding market animals. - Use in feeding market animals. - Know how many pounds a day an average hog should gain. - How to train for show and showmanship techniques. ____ ____ 4. Parts of the pig and terms swine producers use: - Barrow, gilt, boar, sow, farrow, castrate, needle teeth, wasty, weaner, ham, parturition, shote or shoat. ____ ____ 5. Housing and equipment needs. - The importance of worming and what wormer to use. - How to care for your pigs when weather is hot or cold. ____ ____ 6. Efficient management practices. - The importance of worming and a good brand of wormer to use. - Know good preventive measures in swine health care. - How to control lice and mange mites. ____ ____ 7. Identify six breeds of swine and their characteristics. ____ ____ 8. Gestation period of a gilt or sow. ____ ____ 9. Approved farrowing practices. ____ ____ 10. How to maintain accurate project records. -

Ordinary Supplement to the ''Official Gazette” No

Ordinary supplement to the ‘‘Official Gazette” no. 77 of 2 April 2007 – General series Postal subscription 45% - art. 2, para. 20/b Law 23-12-1996, no. 662 - Rome branch OFFICIAL GAZETTE OF THE ITALIAN REPUBLIC PUBLISHED EVERY DAY FIRST PART Rome - Monday, 2 April 2007 EXCEPT HOLIDAYS DIRECTION AND EDITION BY MINISTRY OF JUSTICE – OFFICE FOR PUBLICATION OF LAWS AND DECREES - VIA ARENULA 70 - 00186 ROME ADMINISTRATION BY THE STATE PRINTING OFFICE AND MINT – STATE LIBRARY - PIAZZA G. VERDI 10 - 00198 ROME - SWITCHBOARD 06 85081 No. 92 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND FORESTRY POLICIES PROVISION of 21 March 2007. Production specification for the protected designation of origin “Prosciutto di San Daniele” [San Daniele ham] 2-4-2007 Ordinary supplement to the OFFICIAL GAZETTE General series – no. 77 SUMMARY __________ MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND FORESTRY POLICIES PROVISION of 21 March 2007. – Production specification for the protected designation of origin “Prosciutto di San Daniele” .................................................... P. 5 GENERAL SPECIFICATION .............................................................................................................. P. 7 3 ― ― 2-4-2007 Ordinary supplement to the OFFICIAL GAZETTE General series – no. 77 MINISTERIAL DECREES, RESOLUTIONS AND ORDINANCES MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND FORESTRY POLICIES PROVISION of 21 March 2007. Production specification for the protected designation of origin “Prosciutto di San Daniele” THE GENERAL DIRECTOR FOR THE QUALITY OF AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD PRODUCTS Considering that with (EC) Regulation no. 1107/1996 of the Commission of 12 June 1996, the designation “Prosciutto di San Daniele” with reference to the meat preparation category was registered as Protected Designation of Origin in the register of protected designations of origin (P.D.O.) and protected geographical indications (P.G.I.) specified by art. -

An Investigation Into the Swine of Ancient Egypt

Institutionen för arkeologi och antik historia An Investigation into the Swine of Ancient Egypt Philip Eriksson Fig. 1. A Modern pig in El-Bayadiya. Kandidatuppsats 15 hp I Egyptologi VT 2019 Handledare: Sami Uljas 1 Abstract Eriksson P. 2019. En Undersökning av Grisen i Antika Egypten Grisen var en viktig del av kosten för delar av befolkningen i Egypten från den för- Dynastiska perioden och framåt. Trots omfattande benfynd är grisen sällan avbildad eller noterad i egyptisk ikonografi eller litteratur. Den här studien har som mål att beskriva varför grisen sällan var avbildad eller nedtecknad under den Dynastiska perioden från det Gamla Riket fram till det Nya Riket. Det finns flera teorier som beskriver varför grisen är sällan förekommande i bild och skrift från tidsperioden, främst ekonomiska, sociala och kulturella. Dessa teorier beskrivs och analyseras i uppsatsen. Källorna består av tidigare forskning och utgrävningsrapporter: Fynden är i huvudsak gjorda i bosättningar för arbetarklassen. Ett fåtal egyptiska texter och avbildningar med relevans för grisar kommer också att analyseras. Fynd från bosättningar indikerar att grisen var en viktig källa till protein i de byar som dominerades av hantverkare och bönder. Teorier som bygger på att det fanns religiösa eller kulturella tabun mot grisen har knappast stöd av fynd eller andra ursprungliga källor. Istället indikerar frånvaron av grisen i tidens litteratur och andra avbildningar att den hade ett begränsat ekonomiskt värde för den styrande klassen. Det torde vara det huvudsakliga skälet till varför man inte ansåg grisen vara värdig eller relevant att avbilda. Nyckelord: Grisar, Svin, Socio-Ekonomiska Faktorer, Antika Egypten, Mat, Bosättningar, Arbetarnas By, Tabu Eriksson P.