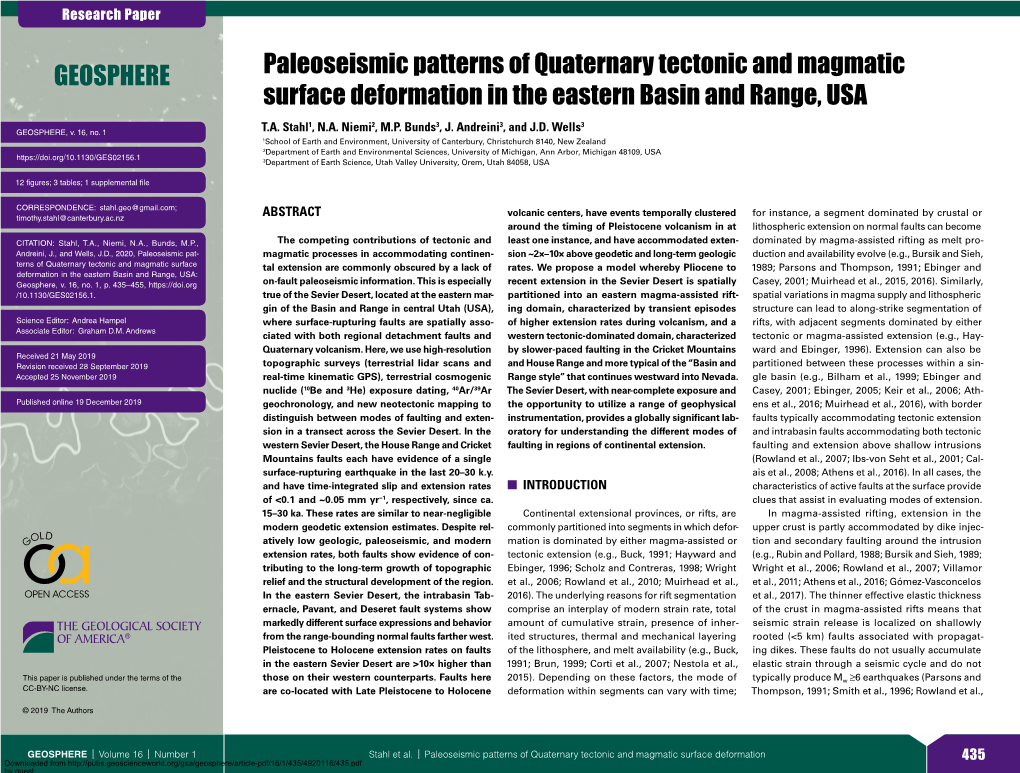

Paleoseismic Patterns of Quaternary Tectonic and Magmatic Surface Deformation in the Eastern Basin and Range, USA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Arctic Nation a U.S

Connecting the United States to the Arctic OUR ARCTIC NATION A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative Cover Photo: Cover Photo: Hosting Arctic Council meetings during the U.S. Chairmanship gave the United States an opportunity to share the beauty of America’s Arctic state, Alaska—including this glacier ice cave near Juneau—with thousands of international visitors. Photo: David Lienemann, www. davidlienemann.com OUR ARCTIC NATION Connecting the United States to the Arctic A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 Alabama . .2 14 Illinois . 32 02 Alaska . .4 15 Indiana . 34 03 Arizona. 10 16 Iowa . 36 04 Arkansas . 12 17 Kansas . 38 05 California. 14 18 Kentucky . 40 06 Colorado . 16 19 Louisiana. 42 07 Connecticut. 18 20 Maine . 44 08 Delaware . 20 21 Maryland. 46 09 District of Columbia . 22 22 Massachusetts . 48 10 Florida . 24 23 Michigan . 50 11 Georgia. 26 24 Minnesota . 52 12 Hawai‘i. 28 25 Mississippi . 54 Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska. Photo: iStock.com 13 Idaho . 30 26 Missouri . 56 27 Montana . 58 40 Rhode Island . 84 28 Nebraska . 60 41 South Carolina . 86 29 Nevada. 62 42 South Dakota . 88 30 New Hampshire . 64 43 Tennessee . 90 31 New Jersey . 66 44 Texas. 92 32 New Mexico . 68 45 Utah . 94 33 New York . 70 46 Vermont . 96 34 North Carolina . 72 47 Virginia . 98 35 North Dakota . 74 48 Washington. .100 36 Ohio . 76 49 West Virginia . .102 37 Oklahoma . 78 50 Wisconsin . .104 38 Oregon. 80 51 Wyoming. .106 39 Pennsylvania . 82 WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE AN ARCTIC NATION? oday, the Arctic region commands the world’s attention as never before. -

A Comprehensive Ecological Land Classification for Utah's West Desert

Western North American Naturalist Volume 65 Number 3 Article 1 7-28-2005 A comprehensive ecological land classification for Utah's West Desert Neil E. West Utah State University Frank L. Dougher Utah State University and Montana State University, Bozeman Gerald S. Manis Utah State University R. Douglas Ramsey Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation West, Neil E.; Dougher, Frank L.; Manis, Gerald S.; and Ramsey, R. Douglas (2005) "A comprehensive ecological land classification for Utah's West Desert," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 65 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol65/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 65(3), © 2005, pp. 281–309 A COMPREHENSIVE ECOLOGICAL LAND CLASSIFICATION FOR UTAH’S WEST DESERT Neil E. West1, Frank L. Dougher1,2, Gerald S. Manis1,3, and R. Douglas Ramsey1 ABSTRACT.—Land managers and scientists need context in which to interpolate between or extrapolate beyond discrete field points in space and time. Ecological classification of land (ECL) is one way by which these relationships can be made. Until regional issues emerged and calls were made for ecosystem management (EM), each land management institution chose its own ECLs. The need for economic efficiency and the increasing availability of geographic informa- tion systems (GIS) compel the creation of a national ECL so that communication across ownership boundaries can occur. -

Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 Is a Mountainous, Deeply Dissected, and Westerly Tilting Fault Block

5 . S i e r r a N e v a d a Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 is a mountainous, deeply dissected, and westerly tilting fault block. It is largely composed of granitic rocks that are lithologically distinct from the sedimentary rocks of the Klamath Mountains (78) and the volcanic rocks of the Cascades (4). A Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, Vegas, Reno, and Carson City areas. Most of the state is internally drained and lies Literature Cited: high fault scarp divides the Sierra Nevada (5) from the Northern Basin and Range (80) and Central Basin and Range (13) to the 2 2 . A r i z o n a / N e w M e x i c o P l a t e a u east. Near this eastern fault scarp, the Sierra Nevada (5) reaches its highest elevations. Here, moraines, cirques, and small lakes and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial within the Great Basin; rivers in the southeast are part of the Colorado River system Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the Ecoregion 22 is a high dissected plateau underlain by horizontal beds of limestone, sandstone, and shale, cut by canyons, and United States (map): Washington, D.C., USFS, scale 1:7,500,000. are especially common and are products of Pleistocene alpine glaciation. Large areas are above timberline, including Mt. Whitney framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and those in the northeast drain to the Snake River. -

The Confusion Range, West-Central Utah: Fold-Thrust Deformation and a Western Utah Thrust Belt in the Sevier Hinterland

The Confusion Range, west-central Utah: Fold-thrust deformation and a western Utah thrust belt in the Sevier hinterland David C. Greene* Department of Geosciences, Denison University, Granville, Ohio 43023, USA ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION tions together while delineating the lateral and oblique thrust ramps that form a signifi cant The Confusion Range in west-central Utah The Confusion Range is a collection of ridges complicating factor in the structure of the fold- has been considered a broad structural trough and small ranges that together form a low moun- thrust system. Together, these fi ve cross sections or synclinorium with little overall shorten- tain range in western Utah, between the more total almost 300 km in map length. Enlarged ing. However, new structural studies indicate imposing Snake Range on the west and House versions of the cross sections at a scale of that the Confusion Range is more accurately Range on the east (Figs. 1 and 2). The range is 1:50,000, along with a discussion of the petro- characterized as an east-vergent, fold-thrust named for its “rugged isolation and confusing leum potential of the region, may be found in system with ~10 km of horizontal shortening topography” (Van Cott, 1990). The Confusion Greene and Herring (2013). during Late Jurassic to Eocene Cordilleran Range exposes ~5000 m of Ordovician through Similar structural style and fold-thrust struc- contractional deformation. For this study, Triassic strata in what has been considered a tures are continuous southward throughout the four balanced and retrodeformable cross broad structural trough or synclinorium (e.g., length of the originally proposed synclinorium, sections across the Confusion Range and Hose, 1977; Anderson, 1983; Hintze and Davis, forming a fold-thrust belt more than 130 km in adjacent Tule Valley were constructed using 2003; Rowley et al., 2009). -

Quaternary Tectonics of Utah with Emphasis on Earthquake-Hazard Characterization

QUATERNARY TECTONICS OF UTAH WITH EMPHASIS ON EARTHQUAKE-HAZARD CHARACTERIZATION by Suzanne Hecker Utah Geologiral Survey BULLETIN 127 1993 UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY a division of UTAH DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 0 STATE OF UTAH Michael 0. Leavitt, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Ted Stewart, Executive Director UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY M. Lee Allison, Director UGSBoard Member Representing Lynnelle G. Eckels ................................................................................................... Mineral Industry Richard R. Kennedy ................................................................................................. Civil Engineering Jo Brandt .................................................................................................................. Public-at-Large C. Williatn Berge ...................................................................................................... Mineral Industry Russell C. Babcock, Jr.............................................................................................. Mineral Industry Jerry Golden ............................................................................................................. Mineral Industry Milton E. Wadsworth ............................................................................................... Economics-Business/Scientific Scott Hirschi, Director, Division of State Lands and Forestry .................................... Ex officio member UGS Editorial Staff J. Stringfellow ......................................................................................................... -

Burning Man Geology Black Rock Desert.Pdf

GEOLOGY OF THE BLACK ROCK DESERT By Cathy Busby Professor of Geology University of California Santa Barbara http://www.geol.ucsb.edu/faculty/busby BURNING MAN EARTH GUARDIANS PAVILION 2012 LEAVE NO TRACE Please come find me and Iʼll give you a personal tour of the posters! You are here! In one of the most amazing geologic wonderlands in the world! Fantastic rock exposure, spectacular geomorphic features, and a long history, including: 1. PreCambrian loss of our Australian neighbors by continental rifting, * 2. Paleozoic accretion of island volcanic chains like Japan (twice!), 3. Mesozoic compression and emplacement of a batholith, 4. Cenozoic stretching and volcanism, plus a mantle plume torching the base of the continent! Let’s start with what you can see on the playa and from the playa: the Neogene to Recent geology, which is the past ~23 million years (= Ma). Note: Recent = past 15,000 years http://www.terragalleria.com Then we’ll “build” the terrane you are standing on, beginning with a BILLION years ago, moving through the Paleozoic (old life, ~540-253 Ma), Mesozoic (age of dinosaurs, ~253-65 Ma)) and Cenozoic (age of mammals, ~65 -0 Ma). Neogene to Recent geology Black Rock Playa extends 100 miles, from Gerlach to the Jackson Mountains. The Black Rock Desert is divided into two arms by the Black Rock Range, and covers 1,000 square miles. Empire (south of Gerlach)has the U.S. Gypsum mine and drywall factory (brand name “Sheetrock”), and thereʼs an opal mine at base of Calico Mtns. Neogene to Recent geology BRP = The largest playa in North America “Playa” = a flat-bottomed depression, usually a dry lake bed 3,500ʼ asl in SW, 4,000ʼ asl in N Land speed record: 1997 - supersonic car, 766 MPH Runoff mainly from the Quinn River, which heads in Oregon ~150 miles north. -

North American Deserts Chihuahuan - Great Basin Desert - Sonoran – Mojave

North American Deserts Chihuahuan - Great Basin Desert - Sonoran – Mojave http://www.desertusa.com/desert.html In most modern classifications, the deserts of the United States and northern Mexico are grouped into four distinct categories. These distinctions are made on the basis of floristic composition and distribution -- the species of plants growing in a particular desert region. Plant communities, in turn, are determined by the geologic history of a region, the soil and mineral conditions, the elevation and the patterns of precipitation. Three of these deserts -- the Chihuahuan, the Sonoran and the Mojave -- are called "hot deserts," because of their high temperatures during the long summer and because the evolutionary affinities of their plant life are largely with the subtropical plant communities to the south. The Great Basin Desert is called a "cold desert" because it is generally cooler and its dominant plant life is not subtropical in origin. Chihuahuan Desert: A small area of southeastern New Mexico and extreme western Texas, extending south into a vast area of Mexico. Great Basin Desert: The northern three-quarters of Nevada, western and southern Utah, to the southern third of Idaho and the southeastern corner of Oregon. According to some, it also includes small portions of western Colorado and southwestern Wyoming. Bordered on the south by the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts. Mojave Desert: A portion of southern Nevada, extreme southwestern Utah and of eastern California, north of the Sonoran Desert. Sonoran Desert: A relatively small region of extreme south-central California and most of the southern half of Arizona, east to almost the New Mexico line. -

Controls on Geothermal Activity in the Sevier Thermal Belt, Southwestern

PROCEEDINGS, 44th Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering Stanford University, Stanford, California, February 11-13, 2019 SGP-TR-214 Controls of Geothermal Resources and Hydrothermal Activity in the Sevier Thermal Belt Based on Fluid Geochemistry Stuart F. Simmons1,2, Stefan Kirby3, Rick Allis3, Phil Wannamaker1 and Joe Moore1 1EGI, University of Utah, 423 Wakara Way, suite 300, Salt Lake City, UT 2Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Utah, 50 S. Central Campus Dr., Salt Lake City, UT 84112 3Utah Geological Survey, 1594 W. North Temple St., Salt Lake City, UT 84114 [email protected] Keywords: Sevier Thermal Belt, hydrothermal systems, heat flow, geochemistry, helium isotopes, stable isotopes. ABSTRACT The Sevier Thermal Belt, southwestern Utah, covers 20,000 km2, and it is located along the eastern edge of the Basin and Range, extending east into the transition zone of the Colorado Plateau. The belt encompasses the geothermal production fields at Cove Fort, Roosevelt Hot Springs, and Thermo, scattered hot spring activity, and the Covenant & Providence hydrocarbon fields. Regionally, it is characterized by elevated heat flow, modest seismicity, and Quaternary basalt-rhyolite magmatism. There are at least five large discrete domains (50 to >500 km2) with anomalous heat flow, including ones associated with Roosevelt Hot Springs, Cove Fort, Thermo and the Black Rock desert. Helium isotope data indicate connections to the upper mantle are developed over the region of strongest and most concentrated hydrothermal activity. By contrast, stable isotope data demonstrate that most of the convective heat transfer is associated with shallow to deep circulation of local meteoric water. Quartz-silica geothermometry suggests that convective heat transfer is compartmentalized by stratigraphic horizons and sub-vertical faults. -

Rose-Marcella-Thesis-2020.Pdf

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Nebkha Morphology, Distribution and Stability Black Rock Playa, Nevada A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Geography By Marcella Rose December 2019 The thesis of Marcella Rose is approved: _______________________________________ _____________ Dr. Julie Laity Date _______________________________________ _____________ Dr. Thomas Farr Date _______________________________________ _____________ Dr. Amalie Orme, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Acknowledgements Dr. Orme, I really don’t think that there is a sufficient combination of words that exist to properly express the immense amount of gratitude I feel for everything that you have done for me. This college education changed my life for the better and I hope you realize what a significant role you were within that experience. I am thankful that not only did I get a great professor, but also a friend. Dr. Laity, thank you so much for having faith in me and for taking me on as one of your last students to advise. But most of all, thank you for pushing me to be better – I needed that. Dr. Farr, I was so excited during DEVELOP that you accepted to be a part of my committee. It was a pleasure to work with you within the Black Rock Playa research team but then to also take our research a step further for this graduate thesis. I would also like to thank the staff at the Bureau of Land Management, Winnemucca: Dr. Mark E. Hall, Field Manager of the Black Rock Field Office; Shane Garside, Black Rock Station Manager/ Outdoor Recreation Planner; Brian McMillan, Rangeland Management Technician; and Braydon Gaard, Interim Outdoor Recreation Planner. -

Ground-Water Resources-Reconnaissance Series Report 20

- STATE OF NEVADA ~~~..._.....,.,.~.:RVA=rl~ AND NA.I...U~ a:~~::~...... _ __,_ Carson City_ GROUND-WATER RESOURCES-RECONNAISSANCE SERIES REPORT 20 GROUND- WATER APPRAISAL OF THE BLACK ROCK DESERT AREA NORTHWESTERN NEVADA By WILLIAM C. SINCLAIR Geologist Price $1.00 PLEASE DO NOT REMO V~ f ROM T. ':'I S OFFICE ;:: '· '. ~- GROUND-WATER RESOURCES--RECONNAISSANCE SERIES .... Report 20 =· ... GROUND-WATER APPRAISAL OF THE BLACK ROCK OESER T AREA NORTHWESTERN NEVADA by William C. Sinclair Geologist ~··· ··. Prepared cooperatively by the Geological SUrvey, U. S. Department of Interior October, 1963 FOREWORD This reconnaissance apprais;;l of the ground~water resources of the Black Rock Desert area in northwestern Nevada is the ZOth in this series of reports. Under this program, which was initiated following legislative action • in 1960, reports on the ground-water resources of some 23 Nevada valleys have been made. The present report, entitled, "Ground-Water Appraisal of the Black Rock Desert Area, Northwe$tern Nevada", was prepared by William C. Sinclair, Geologist, U. s. Geological Survey. The Black Rock Desert area, as defined in this report, differs some~ what from the valleys discussed in previous reports. The area is very large with some 9 tributary basins adjoining the extensive playa of Black Rock Desert. The estimated combined annual recharge of all the tributary basins amounts to nearly 44,000 acre-feet, but recovery of much of this total may be difficult. Water which enters into the ground water under the central playa probably will be of poor quality for irrigation. The development of good produci1>g wells in the old lake sediments underlying the central playa appears doubtful. -

Water Resources of Millard County, Utah

WATER RESOURCES OF MILLARD COUNTY, UTAH by Fitzhugh D. Davis Utah Geological Survey, retired OPEN-FILE REPORT 447 May 2005 UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY a division of UTAH DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Although this product represents the work of professional scientists, the Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, makes no warranty, stated or implied, regarding its suitability for a particular use. The Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, shall not be liable under any circumstances for any direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages with respect to claims by users of this product. This Open-File Report makes information available to the public in a timely manner. It may not conform to policy and editorial standards of the Utah Geological Survey. Thus it may be premature for an individual or group to take action based on its contents. WATER RESOURCES OF MILLARD COUNTY, UTAH by Fitzhugh D. Davis Utah Geological Survey, retired 2005 This open-file release makes information available to the public in a timely manner. It may not conform to policy and editorial standards of the Utah Geological Survey. Thus it may be premature for an individual or group to take action based on its contents. Although this product is the work of professional scientists, the Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, makes no warranty, expressed or implied, regarding its suitability for a particular use. The Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, shall not be liable under any circumstances for any direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages with respect to claims by users of this product. -

Management Plan for the Great Basin National Heritage Area Approved April 30, 2013

Management Plan for the Great Basin National Heritage Area Approved April 30, 2013 Prepared by the Great Basin Heritage Area Partnership Baker, Nevada i ii Great Basin National Heritage Area Management Plan September 23, 2011 Plans prepared previously by several National Heritage Areas provided inspiration for the framework and format for the Great Basin National Heritage Area Management Plan. National Park Service staff and documents provided guidance. We gratefully acknowledge these contributions. This Management Plan was made possible through funding provided by the National Park Service, the State of Nevada, the State of Utah and the generosity of local citizens. 2011 Great Basin National Heritage Area Disclaimer Restriction of Liability The Great Basin Heritage Area Partnership (GBHAP) and the authors of this document have made every reasonable effort to insur e accuracy and objectivity in preparing this plan. However, based on limitations of time, funding and references available, the parties involved make no claims, promises or guarantees about the absolute accuracy, completeness, or adequacy of the contents of this document and expressly disclaim liability for errors and omissions in the contents of this plan. No warranty of any kind, implied, expressed or statutory, including but not limited to the warranties of non-infringement of third party rights, title, merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, is given with respect to the contents of this document or its references. Reference in this document to any specific commercial products, processes, or services, or the use of any trade, firm or corporation name is for the inf ormation and convenience of the public, and does not constitute endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the GBHAP or the authors.