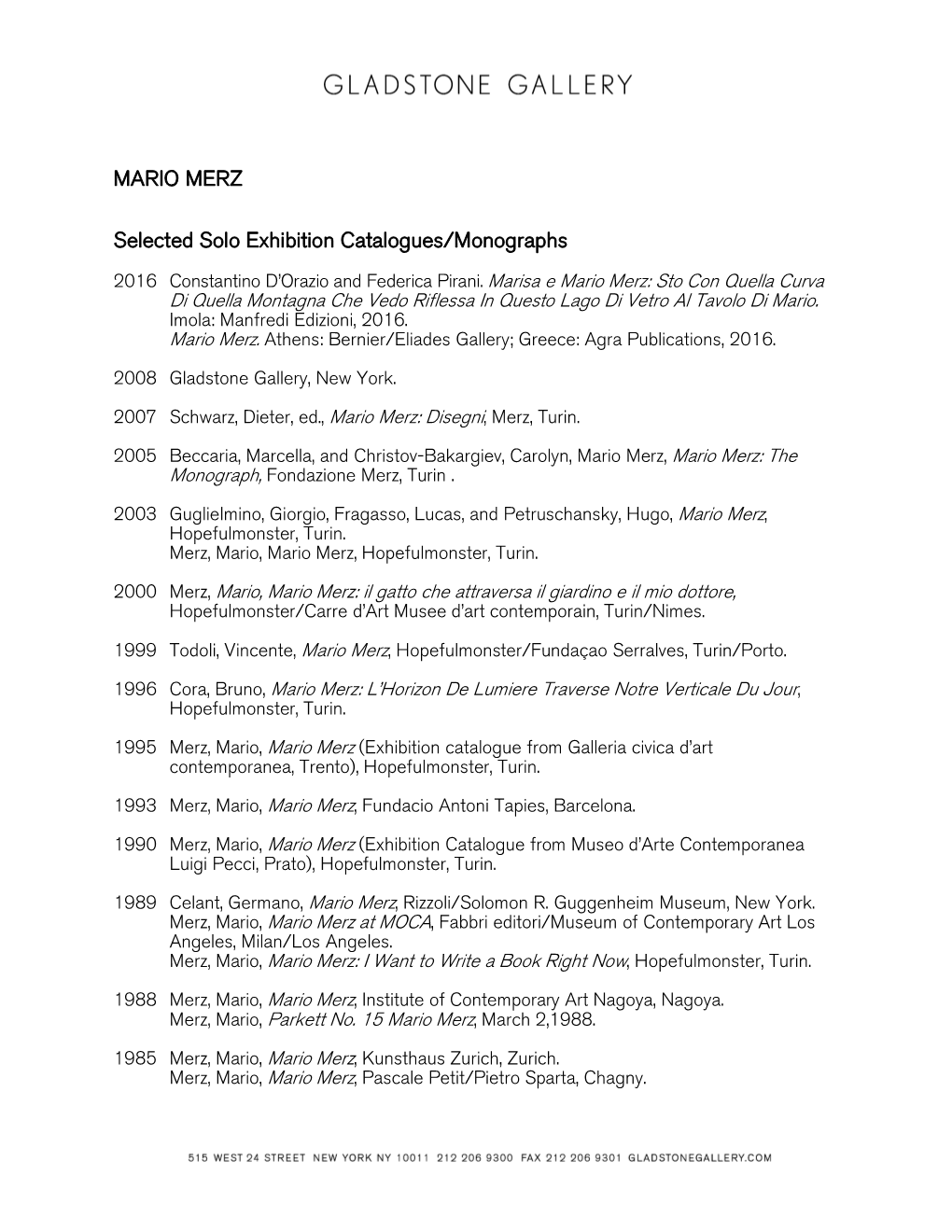

MARIO MERZ Selected Solo Exhibition Catalogues/Monographs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibition of Italian Avant-Garde Art on View at Columbia's Wallach

6 C olumbia U niversity RECORD October 5, 2001 Exhibition of Italian Avant-Garde Art on View at Columbia’s Wallach Gallery An exhibition of Italian 63—a peculiar combination of avant-garde art will be on photography, painting and col- view at Columbia’s Wallach lage in which a life-sized Art Gallery from Oct. 3 to image of the artist, traced from Dec. 8. The exhibition, “Arte a photograph onto thin, Povera: Selections from the translucent paper, is glued on Sonnabend Collection,” will an otherwise empty mirrored draw together major works by panel. Giovanni Anselmo, Pier Paolo The exhibition is drawn Calzolari, Jannis Kounellis, from the rich holdings of the Mario Merz, Giulio Paolini, gallerist Illeana Sonnabend. Michelangelo Pistoletto, Sonnabend has long been rec- Mario Schifano and Gilbert ognized as one of the foremost Zorio, most of which have collectors and promoters of rarely been exhibited in the American art from the 1950s, United States '60s, and '70s. Lesser-known In the late 1960s, a number is her devotion to an entirely of artists working in Italy pro- different artistic phenome- duced one of the most authen- non—the Italian neo-avant- tic and independent artistic garde—which is equally interventions in Europe. impressive. Striking in its Grouped together under the comprehensiveness, the col- term "Arte Povera" in 1967 by lection was assembled by the critic Germano Celant in ref- Sonnabend and her husband, erence to the use of materials— Michael. natural and elemental—the Claire Gilman, a Ph.D. can- artists delivered a powerful and didate in Columbia's depart- timely critique of late mod- ment of art history and arche- ernism, specifically minimalism. -

Download Download

1 Histories of PostWar Architecture 2 | 2018 | 1 1968: It’s Just a Beginning Ester Coen Università degli Studi dell’Aquila [email protected] An expert on Futurism, Metaphysical art and Italian and International avant-gardes in the first half of the twentieth century, her research also extends to the sixties and seventies and the contemporary scene, with numerous essays and other publications. In collaboration with Giuliano Briganti she curated the exhibition Pittura Metafisica (Palazzo Grassi, Venice 1979) and edited the catalogue, while with Maurizio Calvesi she edited the Catalogue Raisonné of Umberto Boccioni’s works (1983). She curated with Bill Lieberman the Boccioni retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of New York in 1988 and has since been involved in many international exhibitions. She organised Richard Serra’s show at the Trajan’s Markets (Rome 1999), planned the Gary Hill show at the Coliseum (Rome 2005) and was one of the three committee members of the Futurism centenary exhibition (Pompidou Paris, Scuderie del Quirinale Rome and Tate Modern London) celebrating in the same year (2009) with Futurism 100: Illuminations. Avant-gardes Compared. Italy-Germany-Russia the anniversary at MART in Rovereto. In 2015 she focused on Matisse’s fascination for decorative arts (Arabesque, Scuderie del Quirinale Rome) and at the end of 2017 a show organized at La Galleria Nazionale in Rome anticipated the fifty years of the 1968 “revolution”. Full professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History at the University of Aquila, she lives in Rome. ABSTRACT 1968 marks the beginning of a social, political and cultural revolution, with all of its internal contradictions. -

The Politics of Arte Povera

Living Spaces: the Politics of Arte Povera Against a background of new modernities emerging as alternatives to centres of tradition in the Italy of the so-called “economic miracle”, a group formed around the critic Germano Celant (1940) that encapsulated the poetry of arte povera. The chosen name (“poor art”) makes sense in the Italy of 1967, which in a few decades had gone from a development so slow it approached underdevelopment to becoming one of the economic dri- ving forces of Europe. This period saw a number of approaches, both nostalgic and ideological, towards the po- pular, archaic and timeless world associated with the sub-proletariat in the South by, among others, the writer Carlo Levi (1902-1975) and the poet and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975). the numbers relate to the workers who join a mensa operaia (workers’ table), a place as much to do with alienation as unionist conspiracy. Arte povera has been seen as “a meeting point between returning and progressing, between memory and anti- cipation”, a dynamic that can be clearly understood given the ambiguity of Italy, caught between the weight of a legendary past and the alienation of industrial develo- pment; between history and the future. New acquisitions Alighiero Boetti. Uno, Nove, Sette, Nove, 1979 It was an intellectual setting in which the povera artists embarked on an anti-modern ap- proach to the arts, criticising technology and industrialization, and opposed to minimalism. Michelangelo Pistoletto. It was no coincidence that most of the movement’s members came from cities within the Le trombe del Guidizio, 1968 so-called industrial triangle: Luciano Fabro (1936-2007), Michelangelo Pistoletto (1933) and Alighiero Boetti (1940-1994) from Turin; Mario Merz (1925-2003) from Milan; Giu- lio Paolini (1940) from Genoa. -

Mario Merz Igloos

Pirelli HangarBicocca presents Mario Merz Igloos Press Preview October 23, 2018, 11.30 AM Opening October 24, 2018, 7 PM From October 25, 2018 to February 24, 2019 Unprecedented gathering of more than 30 ‘igloos’ by Arte Povera pioneer to be displayed over Pirelli HangarBicocca’s 5,500-m2 site Exhibition curated by Vicente Todolí and realised in collaboration with the Fondazione Merz Mario Merz, exhibition view, Kunsthaus Zürich, 1985. Courtesy Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2011.M.30). Photo: Balthasar Burkhardt Pirelli HangarBicocca presents “Igloos” (25 October 2018 – 24 February 2019), a show by Mario Merz (Milan, 1925–2003), bringing together his most iconic group of works: the Igloos, dating from 1968 until the end of his life. Curated by Vicente Todolí, Artistic Director of Pirelli HangarBicocca and realised in collaboration with Fondazione Merz, the exhibition spans the whole 5,500 square metres of the Navate and the Cubo of Pirelli HangarBicocca, placing the visitor at the heart of a constellation of over 30 large-scale works in the shape of an igloo: an unprecedented landscape of great visual impact. Fifty years since the creation of the first igloo, the exhibition provides an overview of Mario Merz’s work, of its historical importance and great innovative reach. Gathered from numerous private collections and international museums, including the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, the Tate Modern in London, the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin and the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, the ‘igloos’ will be displayed together in such a large number for the first time. Vicente Todolí said, “As its starting point, the exhibition ‘Igloos’ takes Mario Merz’s solo show curated by Harald Szeemann in 1985 at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, where all the types of igloos produced up until that point were brought together to be arranged ‘as a village, a town, a ‘Città irreale’ in the large exhibition hall,’ as Szeemann states. -

Introduction*

Introduction* CLAIRE GILMAN If Francesco Vezzoli’s recent star-studded Pirandello extravaganza at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Senso Unico exhibition that ran con- currently at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center are any indication, contemporary Italian art has finally arrived.1 It is ironic if not entirely surprising, however, that this moment occurs at a time when the most prominent trend in Italian art reflects no discernible concern for things Italian. Rather, the media-obsessed antics of Vezzoli or Vanessa Beecroft (featured alongside Vezzoli in Senso Unico) are better understood as exemplifying the precise eradication of national and cultural boundaries that is characteristic of today’s global media culture. Perhaps it is all the more fitting, then, that this issue of October returns to a rather different moment in Italian art history, one in which the key practition- ers acknowledged the invasion of consumer society while nonetheless striving to keep their distance; and in which artists responded to specific national condi- tions rooted in real historical imperatives. The purpose of this issue is twofold: first, to give focused scholarly attention to an area of post–World War II art history that has gained increasing curatorial exposure but still receives inadequate academic consideration. Second, in doing so, it aims to dismantle some of the misconceptions about the period, which is tra- ditionally divided into two distinct moments: the assault on painting of the 1950s and early ’60s by the triumverate Alberto Burri, Lucio Fontana, and Piero Manzoni, followed by Arte Povera’s retreat into natural materials and processes. -

Mario Merz Biography

Mario Merz Milan, 1925-2003 Mario Merz was born on 1 January 1925 in Milan and moved with his family, of Swiss origin, to Turin as a child. During the Second World War, he abandoned his university studies in medicine and played an active part in the partisan struggle against the fascists. Arrested in 1945 while distributing leaflets, he began to draw in prison. After his release from jail, encouraged by his friend Luciano Pistoi, he decided to devote himself entirely to painting and in 1954 he opened his first solo exhibition at the Galleria La Bussola in Turin, where he presented a series of works painted in an expressionist style. In the mid-1960s, Merz’s work evolved towards a form of experimentation that led him to create his so- called “volumetric paintings” (Mila Pistoi): constructions of canvases incorporating objets trouvés and organic or industrial materials, whose incorporation into the work helped position the artist among the new exponents of Arte Povera. Everyday objects and consumables – a basket, a saucepan, a mackintosh – organic items – a bundle of twigs, beeswax, clay – technical materials – metal rods, wire mesh, glass, neon – and quotations of literary and other origin, manifested themselves as energies hitherto neglected by artists and which Merz unleashed in “a sum of interior projections onto objects”, sometimes translating them “directly in the objects” (Germano Celant), reinterpreting them by repositioning them in a panorama of new forms and statements. The igloo (1969) and the table (1973) made their appearance as regular items: one is an “ideal organic form, at once a world and a small house” that the artist claimed could be lived in, an absolute space that is not modelled but is “a hemisphere resting on the ground”; the other is “the first thing to determine space, a piece of raised earth, like a rock in the landscape”. -

The Politics of Arte Povera

Living Spaces: the Politics of Arte Povera Against a background of new modernities emerging as alternatives to centres of tradition in the Italy of the so- called “economic miracle”, a group formed around the critic Germano Celant (1940) that encapsulated the po- etry of arte povera. The chosen name (“poor art”) makes sense in the Italy of 1967, which in a few decades had gone from a development so slow it approached underdevelopment to becoming one of the economic driving forces of Europe. This period saw a number of approaches, both nostalgic and ideological, towards the popular, archaic and timeless world associated with the sub-proletariat in the South by, among others, the writer Carlo Levi (1902-1975) and the poet and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975). Fibonacci Napoli (Fabricca a San Giovan- ni a Teduccio), 1971, a work which pre- sents a numerical sequence that com- plicates and humanizes the simplistic logic of minimalist artists, while adding a political component: the numbers relate to the workers who join a mensa operaia (workers’ table), a place as much to do with alienation as unionist conspiracy. Arte povera has been seen as “a meeting point between returning and progressing, between memory and anticipation”, a dynamic that can be clearly understood given the ambiguity of Italy, caught be- tween the weight of a legendary past and the alienation of industrial development; between history and the future. It was an intellectual setting in which the povera artists embarked on an anti-modern approach to the arts, criticising technology and industrialization, and opposed to min- imalism. -

Moma EXHIBITION SPANS the ENTIRE CAREER of ALIGHIERO BOETTI, ONE of the MOST IMPORTANT and INFLUENTIAL ARTISTS of HIS GENERATION

MoMA EXHIBITION SPANS THE ENTIRE CAREER OF ALIGHIERO BOETTI, ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT AND INFLUENTIAL ARTISTS OF HIS GENERATION Alighiero Boetti: Game Plan July 1–October 1, 2012 The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Gallery, sixth floor The Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium, second floor NEW YORK, June 26, 2012—Alighiero Boetti: Game Plan marks the largest presentation of works by Alighiero Boetti (Italian, 1940–1994) in the United States to date. A full retrospective spanning the artist’s entire career, the exhibition will be on view in two locations in the Museum from July 1 to October 1, 2012. Celebrating the material diversity, conceptual complexity, and visual beauty of Boetti’s work, the exhibition brings together approximately 100 works across many mediums that address Boetti’s ideas about order and disorder, non-invention, and the way in which the work is concerned with the whole world, travel, and time. Proving him to be one of the most important and influential international artists of his generation, the exhibition focuses on several thematic threads, demonstrating the artist’s interest in exploring recurring motifs in his work instead of a linear development. In The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Gallery on the sixth floor, the exhibition will feature works from the first 15 years of the artist’s career, while works in the Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium on the second floor are drawn from the latter part of his career, focused on Boetti’s embroidered pieces and woven rugs. -

Mimmo Paladino. Biography 1948 Born in Paduli (Benevento) On

Mimmo Paladino. Biography 1948 Born in Paduli (Benevento) on December 18th. 1964 He visits the Venice Biennial where Robert Rauschemberg’s work in the American Pavilion make a strong impression on him, revealing to him the reality of art. 1968 He graduates from the arts secondary school of Benevento. He holds an exhibition presented by Achille Bonito Oliva, at the Portici Gallery (Naples). 1969 Enzo Cannaviello’s Lo Studio Oggetto in Caserta organizes his solo exhibition. 1973 He begins to combine images in mixed technique, creating a complex iconography that takes into account an extraordinary mix of messages, strangely opposed and divergent, yet blended together. 1977 He moves to Milan. 1978 First trip to New York. 1980 He is invited by Achille Bonito Olivo to participate in the Aperto ’80 at the Venice Biennial along with Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente, Enzo Cucchi and Nicola De Maria. He publishes the book EN-DE-RE with Emilio Mazzoli in Modena. 1981 He participates in A New Spirit in Painting at the London Royal Academy of Art. The Kunstmuseum of Basel and the Kestner-Gesellshaft of Hannover organize a large exhibitions of drawings made from 1976 to 1981. The exhibition moves from the Kestner-Gesellshaft in Hannover to the Mannheimer Kunstverein in Mannheim and the Groninger Museum in Groningen, launching Paladino as an international artist. 1982 He participates in Documenta 7 in Kassel and the Sydney Biennial. He makes his first bronze sculpture, Giardino Chiuso. First trip to Brazil, where his father lives. 1984 He builds a house and studio in Paduli near Benevento and from this point on divides his time between Paduli and his Milan apartment. -

Press Release Prize Inglese

Mario Merz Prize International Art and Music Prize Finalists Exhibition and Opening Call for Entries for the Second Edition Exhibition dates: 29 January – 12 April 2015 (opening 29 January at 6pm) Fondazione Merz (Via Limone 24 – Torino) Application period: 29 January – 31 May 2015 The Fondazione Merz is pleased to present the exhibition of the 5 finalists selected for the Art Section in this first edition of the Mario Merz Prize. Artists Lida Abdul (Kabul 1973), Glenn Ligon (New York 1960), Naeem Mohaiemen (London 1969), Anri Sala (Tirana 1974) and Wael Shawky (Alexandria 1971) were shortlisted—among over 500 nominees—by members of the pre-selection judging panel, Marisa Merz, Beatrix Ruf (director Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam) and Claudia Gioia (independent curator). Curated by Beatrice Merz, the exhibition project showcases two or more pieces by each of the finalists, selected among their most significant works. The public is invited to vote for their favorite artist by visiting the exhibition or logging onto the website (mariomerzprize.org) to view and judge the artwork online. The public vote will be added to the votes cast by Jury, whose members are: Manuel Borja-Villel (Director Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid), Massimiliano Gioni (Head Curator New Museum, New York – Art Director Fondazione Trussardi, Milan), Lawrence Weiner (artist), and Beatrice Merz. Free entrance for both exhibition and concert. “The Prize—which is not state-funded, but relies solely on private funding—originates from an idea of openness and participation”—say Beatrice and Willy Merz. “For this reason, and as we ask the public to actively participate by Fondazione Merz via limone 24 10141 turin italy [email protected] casting their vote, we chose, together with the Organizing Committee, not to charge an admission fee for the exhibition, nor the concert”. -

Press Release (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y 13 January 2006 PRESS RELEASE GAGOSIAN GALLERY 6-24 BRITANNIA STREET T. 020.7841.9960 LONDON WC1X 9JD F. 020. 7841.9961 GALLERY HOURS: Tue – Sat 10:00am– 6:00pm MARIO MERZ: 8-5-3 Friday, 10 February – Saturday, 18 March 2006 Opening reception: Thursday, February 9th, 6 – 8pm Gagosian Gallery is pleased to announce a large-scale installation by the Italian artist Mario Merz (1925 – 2003). The work, titled 8-5-3, was first shown at Kunsthaus Zurich in 1985 and it features three igloos constructed from metal and glass, covered with fragments of clamps and twigs, and linked by neon tubes. The phrase Objet cache-toi or ‘a hiding place’ stretches across the structure in red neon lights. In 1968 Merz produced Giap’s Igloo, the first of these archetypal dwellings that have become his signature works. Through the igloo motif Merz explores the fundamentals of human existence: shelter, nourishment and humanity’s relationship to nature. He examines the lost purity of pre- industrial societies as well as the changing, nomadic identity of modern man. Merz’s igloos are comprised of diverse materials including the organic and the artificial, the opaque and the transparent, the heavy and the lightweight. The title of the exhibition, 8-5-3, corresponds to the diameter of each of the three igloos. Furthermore, it refers to the Fibonacci sequence, a mathematical series of numbers recognized in the 13th century. In this sequence, each numeral is equal to the sum of the two that precede it: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, and so on. -

Mimmo Paladino (1948 - )

Mimmo Paladino (1948 - ) Isola Watercolour. Signed, titled, inscribed and dated Agosto 1982 ISOLA / Argentouli.(?) casa pellica(?) / Mimmo Paladino on the verso. 255 x 333 mm. (10 x 13 1/8 in.) As the artist has stated, ‘I really draw. It is easy for me. In reality, the less struggle there is for me the better I produce. It is not that I have a mentality that preplans, but I feel that drawing is about the impalpable…transparency.’ Executed in August 1982, this watercolour can be related to a later painting of the same title L’Isola (The Island), dating from 1993 and depicting a human figure resting alongside a small island in the midst of a sea, in the Würth collection in Germany. Provenance: Acquired from the artist by Galerie Bel’Art, Stockholm Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 27 June 1985, lot 763 Stanley J. Seeger, London. Artist description: A sculptor, painter and printmaker, Domenico (Mimmo) Paladino was a leading member of the Italian artistic movement known as Transavanguardia. The term, which can be translated as ‘beyond the avant- garde’, was coined by the art critic and curator Achille Bonito Oliva in 1979 to refer to a small group of young Italian artists - Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente, Enzo Cucchi, Nicolo de Maria and Paladino - who each displayed a neo-expressionist tendency in their work. The artists of the Transavanguardia group came to public prominence at the 1980 Venice Biennale, and at the height of its success in the 1980s was to become one of the most influential artistic movements of post-war Italian art.