Arthur Chaskalson Session #1 (Video)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To See the Conference Programme

For all administrative related queries please contact: Ms Jemima Thomas (who will be available on-site on Friday and Saturday evenings) Cell-phone: 073 4888 874 E-mail: [email protected] For additional conference related assistance please contact Ms Vitima Jere Cell-phone: 079 664 7454 E-mail: [email protected] Copyright vests in the authors of the papers All information correct at time of going to press Dear LSA in Africa Delegates, Welcome to South Africa’s Mother City, and the first formal Law and Society conference to be held on the African continent. The Centre for Law and Society, along with the Law and Society Association, is proud to host such an exciting, and diverse, collection of scholars and papers – all focused on the African continent. The idea for this conference germinated at a roundtable held at the 2014 LSA Annual Meeting in Minneapolis, where a large number of scholars convened to discuss how they may envision a more global socio-legal field. The discussion recognised that while LSA had served as a major hub for socio-legal scholars drawn from many countries, existing networks tended to favour themes and ideas that originated in, and primarily benefitted, scholars from the North. From the perspective of scholars from the Global South, any exchange, when it did happen, tended to be rather lopsided, favouring Northern theory and scholarship. The Committee on the 2nd Half Century, appointed by Presidents Michael McCann and Carroll Seron, and led by Eve Darian-Smith and Greg Shaffer, concluded that LSA could take a number of steps to improve this situation. -

The Constitutional Court of South Africa: Rights Interpretation and Comparative Constitutional Law

THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA: RIGHTS INTERPRETATION AND COMPARATIVE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW Hoyt Webb- I do hereby swear that I will in my capacity asJudge of the Constitu- tional Court of the Republic of South Africa uphold and protect the Constitution of the Republic and the fundamental rights entrenched therein and in so doing administerjustice to all persons alike with- out fear,favour or prejudice, in accordance with the Constitution and the Law of the Republic. So help me God. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Schedule 3 (Oaths of Office and Solemn Affirmations), Act No. 200, 1993. I swear that, asJudge of the ConstitutionalCourt, I will be faithful to the Republic of South Africa, will uphold and protect the Consti- tution and the human rights entrenched in it, and will administer justice to all persons alike withwut fear,favour or prejudice, in ac- cordancewith the Constitution and the Law. So help me God. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, Schedule 2 (Oaths and Solemn Affirmations), Act 108 of 1996. I. INTRODUCTION In 1993, South Africa adopted a transitional or interim Constitu- tion (also referred to as the "IC"), enshrining a non-racial, multiparty democracy, based on respect for universal rights.' This uras a monu- mental achievement considering the complex and often horrific his- tory of the Republic and the increasing racial, ethnic and religious tensions worldwide.2 A new society, however, could not be created by Hoyt Webb is an associate at Brown and Wood, LLP in NewYork City and a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations. -

Appointments to South Africa's Constitutional Court Since 1994

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 15 July 2015 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Johnson, Rachel E. (2014) 'Women as a sign of the new? Appointments to the South Africa's Constitutional Court since 1994.', Politics gender., 10 (4). pp. 595-621. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X14000439 Publisher's copyright statement: c Copyright The Women and Politics Research Section of the American 2014. This paper has been published in a revised form, subsequent to editorial input by Cambridge University Press in 'Politics gender' (10: 4 (2014) 595-621) http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=PAG Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Rachel E. Johnson, Politics & Gender, Vol. 10, Issue 4 (2014), pp 595-621. Women as a Sign of the New? Appointments to South Africa’s Constitutional Court since 1994. -

32/18 in the Application Of: the UN SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR on THE

IN THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA Case No: 32/18 In the application of: THE UN SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE RIGHTS TO FREEDOM OF PEACEFUL Applicant for leave to ASSEMBLY AND OF ASSOCIATION intervene as amicus curiae In the matter between: PHUMEZA MLUNGWANA First Applicant XOLISWA MBADISA Second Applicant LUVO MANKQO Third Applicant NOMHLE MACI Fourth Applicant ZINGISA MRWEBI Fifth Applicant MLONDOLOZI SINUKU Sixth Applicant VUYOLWETHU SINUKU Seventh Applicant EZETHU SEBEZO Eighth Applicant NOLULAMA JARA Ninth Applicant ABDURRAZACK ACHMAT Tenth Applicant and THE STATE First Respondent THE MINISTER OF POLICE Second Respondent NOTICE OF APPLICATION: RULE 10 PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that the applicant for leave to intervene intends to apply to this Court, on a dated to be determined by the Registrar, for an order in the following terms – 1. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association is admitted to these proceedings as amicus curiae. 2. The amicus curiae is granted – 2.1. the right to lodge written argument; and 2.2. the right to present oral argument at the hearing of this matter. provided that such argument does not repeat matter set forth in the arguments of the other parties, and raises new contentions which may be useful to the court. 3. Further and/or alternative relief. TAKE NOTICE FURTHER that the affidavit of THULANI NKOSI, together with the annexures thereto, will be used in support of this application. TAKE NOTICE FURTHER that the applicant for leave to intervene has appointed THE SERI LAW CLINIC as his attorneys of record, at the address set out below, where he will accept service of all further notices, documents and other process in connection with these proceedings. -

Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of North Carolina School of Law NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND COMMERCIAL REGULATION Volume 26 | Number 3 Article 5 Summer 2001 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Stephen Ellman, To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity, 26 N.C. J. Int'l L. & Com. Reg. 767 (2000). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This comments is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity* Stephen Ellmann** Brain Fischer could "charm the birds out of the trees."' He was beloved by many, respected by his colleagues at the bar and even by political enemies.2 He was an expert on gold law and water rights, represented Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, the most prominent capitalist in the land, and was appointed a King's Counsel by the National Party government, which was simultaneously shaping the system of apartheid.' He was also a Communist, who died under sentence of life imprisonment. -

Unrevised Hansard National

UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL ASSEMBLY TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 Page: 1 TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 ____ PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY ____ The House met at 14:02. The Speaker took the Chair and requested members to observe a moment of silence for prayer or meditation. MOTION OF CONDOLENCE (The late Ahmed Mohamed Kathrada) The CHIEF WHIP OF THE MAJORITY PARTY: Hon Speaker I move the Draft Resolution printed in my name on the Oder Paper as follows: That the House — UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL ASSEMBLY TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 Page: 2 (1) notes with sadness the passing of Isithwalandwe Ahmed Mohamed Kathrada on 28 March 2017, known as uncle Kathy, following a short period of illness; (2) further notes that Uncle Kathy became politically conscious when he was 17 years old and participated in the Passive Resistance Campaign of the South African Indian Congress; and that he was later arrested; (3) remembers that in the 1940‘s, his political activities against the apartheid regime intensified, culminating in his banning in 1954; (4) further remembers that in 1956, our leader, Kathrada was amongst the 156 Treason Trialists together with Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu, who were later acquitted; (5) understands that he was banned and placed under a number of house arrests, after which he joined the political underground to continue his political work; UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL ASSEMBLY TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 Page: 3 (6) further understands that he was also one of the eight Rivonia Trialists of 1963, after being arrested in a police swoop of the Liliesleaf -

PENELOPE (PENNY) ANDREWS Curriculum Vitae

PENELOPE (PENNY) ANDREWS Curriculum Vitae Address: Valparaiso University School of Law 656 S. Greenwich Street Valparaiso IN 46383 Phone: (219) 465-7847 Fax: (219) 465-7872 e:mail: [email protected] and [email protected] LEGAL AND PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Visiting Professor – Valparaiso University School of Law (2007-2008). Courses: (1) International Human Rights Law; (2) Gender and the Law; (3) The Judicial Enforcement of Socio-Economic Rights. Professor of Law - City University of New York Law School at Queens College (since January 1993- tenured 1998). Courses: (1) Torts, (2) International Law and International Human Rights Law; (3) Comparative Law; (4) Gender and Law. Ariel F. Sallows Professor of Human Rights Law – University of Saskatchewan, Canada (Research Chair - January to December 2005). Course: International Human Rights Law. Visiting Professor – Touro Law School Summer Program, University of Potsdam, Germany (June 2004). Course: Human Rights and Social Justice. Visiting Professor – Columbia Law School Summer Program, University of Amsterdam School of Law (July 2003). Course: American Tort Law in Comparative Perspective. Parsons Visitor – Sydney University School of Law, Australia (Fall 2002). Lectures Series on Human Rights and Transitional Justice. Stoneman Endowed Visting Professor in Law and Democracy - Albany Law School (Spring 2002). Courses: (1) The International Protection of Human Rights; (2) Comparative Perspectives on Race and the Law. Visiting Professor, University of Maryland School of Law Summer Program, University of Aberdeen, Scotland (Summer 2001). Course: Comparative Human Rights Law. Visiting Professor - University of Natal, Durban, South Africa (Summer 2000). Course: Public International Law/Human Rights Law. Visiting Professor - University of Maryland School of Law, Baltimore (Spring 1994). -

1 Frank Michelman Constitutional Court Oral History Project 28Th

Frank Michelman Constitutional Court Oral History Project 28th February 2013 Int This is an interview with Professor Frank Michelman, and it’s the 28th of February 2013. Frank, thank you so much for agreeing to participate in the Constitutional Court Oral History Project, we really appreciate your time. FM I’m very much honoured by your inviting me to participate and I’m happy to do so. Int Thank you. I’ve not had the opportunity to interview you before, and I wondered whether you could talk about early childhood memories, and some of the formative experiences that may have led you down a legal and academic professional trajectory? FM Well, that’s going to be difficult, because…because I didn’t have any notion at all prior to my senior year in college, the year before I entered law school, that I would be going to law school. I hadn’t formed, that I can recall, any plan, hope, ambition, in that direction at all. To the extent that I had any distinct career notion in mind during the years before I wound up going to law school? It would have been an academic career, possibly in the field of history, in which I was moderately interested and which was my concentration in college. I had formed a more or less definite idea of applying to graduate programs in history, and turning myself into a history professor. Probably United States history. United States history, or maybe something along the line of what’s now called the field of ideas, which I was calling intellectual history in those days. -

Graduation 2009

GRADUATION 2009 Presentation speech for Sir Sydney Kentridge KCMG QC for the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws of the University honoris causa Chancellor, on a beam in our Hunter Street Library, there is an early piece of Graffiti: it says ‘Burdett and Liberty for Ever’. Although these words were written long before this University was even thought of, many of us still draw inspiration from them. A commitment to Liberty is central to what this University stands for – and it has also been the crucial theme in the life of our Honorand. Chancellor: A good many of Sir Sydney’s cases have centred on issues of freedom and liberty, first in South Africa and later in this country. In South Africa he frequently appeared for leaders of the anti-apartheid movement and his clients included Chief Albert Luthulo, Nelson Madela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu. He is perhaps best known for representing the family of Stephen Biko. Lord Alexander of Weedon wrote of his performance at the Inquest, ‘Through remorseless and deadly cross-questioning, sometimes with brilliant irony, Kentridge established that the founder of the Black Consciousness Movement had been killed by police brutality. The verdict of accidental death was seen as risible’ In this country Sir Sydney has continued to defend freedom. He was so effective when representing the Countryside Alliance in its attempts to stop the proposed ban on fox hunting that he was accused of ‘overstating his case’. Nothing daunted, when the case got to the House of Lords, he began ‘Perhaps I could overstate my case again’. -

Helen Joseph's

Foreword: Helen Joseph’s – If this be Treason – by Benjamin Trisk I was unaware of Helen Joseph’s memoir of the Treason Trial (1956 – 1961) until I came across a letter to I.A. Maisels QC (Isie), who was my father-in-law. I was helping him tidy up some old papers around 1991 or 1992 (he died at the end of 1994) and I found a hand-written letter among his papers. It was addressed to him in an unknown hand and dated 22nd February 1961. A facsimile of the letter is included in this book. Among the signatories to the letter was Helen Joseph.She was one of the activists who was detained and charged with others in December 1956. Between December 5 and December 12, 1956, 156 people were arrested. The charge was High Treason. In those days, there was first a preparatory examination (which concluded in January 1958) and 92 of the 156 were then committed for trial. The others were free to go. The Treason Trial, as it is known, commenced in August 1958. This was known as the First Indictment and the State quickly realized, as a brilliant Defence team first dissected and then destroyed the State’s argument that it would have to withdraw the charges- which it did in October 1958. The State, however, was not giving up and the trial commenced again in January 1959 (the Second Indictment) with a further reduction in the number of the accused. 30 of the original 156 then faced charges from High Treason. Until the time when I found the letter, I had known very little about the Treason Trial. -

The Struggle for the Rule of Law in South Africa

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 60 Issue 1 Twenty Years of South African Constitutionalism: Constitutional Rights, Article 5 Judicial Independence and the Transition to Democracy January 2016 The Struggle for the Rule of Law in South Africa STEPHEN ELLMANN Martin Professor of Law at New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation STEPHEN ELLMANN, The Struggle for the Rule of Law in South Africa, 60 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2015-2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 Stephen Ellmann The Struggle for the Rule of Law in South Africa 60 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. 57 (2015–2016) ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Stephen Ellmann is Martin Professor of Law at New York Law School. The author thanks the other presenters, commentators, and attenders of the “Courts Against Corruption” panel, on November 16, 2014, for their insights. www.nylslawreview.com 57 THE STRUGGLE FOR THE RULE OF LAW IN SOUTH AFRICA NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 I. INTRODUCTION The blight of apartheid was partly its horrendous discrimination, but also its lawlessness. South Africa was lawless in the bluntest sense, as its rulers maintained their power with the help of death squads and torturers.1 But it was also lawless, or at least unlawful, in a broader and more pervasive way: the rule of law did not hold in South Africa. -

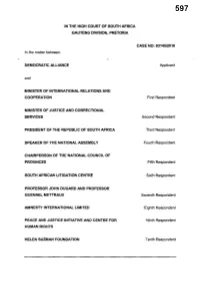

Paginated Bundle 30112016 (Compressed) Part11.Pdf

597 IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA GAUTENG DIVISION, PRETORIA CASE NO: 83145/2016 In the matter between: DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE Applicant and MINISTER OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND COOPERATION First Respondent MINISTER OF JUSTICE AND CORRECTIONAL SERVICES Second Respondent PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA Third Respondent SPEAKER OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY Fourth Respondent CHAIRPERSON OF THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF PROVINCES Fifth Respondent SOUTH AFRICAN LITIGATION CENTRE Sixth Respondent PROFESSOR JOHN DUGARD AND PROFESSOR GUENAEL METTRAUX Seventh Respondent AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL LIMITED Eighth Respondent PEACE AND JUSTICE INITIATIVE AND CENTRE FOR Ninth Respondent HUMAN RIGHTS HELEN SUZMAN FOUNDATION Tenth Respondent 598 2 NOTICE OF SET DOWN - SPECIAL MOTION ROLL BE PLEASED TO SET the above matter down on the roll for hearing on the Special Motion Roll on 05 AND 06 DECEMBER 2016 at 10:00 or as soon as thereafter as Counsel may be heard as per the directive of the Deputy Judge President of the aforementioned court dated 17 November 2016 annexed hereto as ANNEXURE "A". DATED AT PRETORIA on this zrz:vl day of NOVEMBER 2016. Elzanne Jonker Attorneys for the Applicant Tyger Valley Office Park Building Number 2 Cnr Willie van Schaar & Old Oak Roads BELVILLE Ref: DEM16/0300 JONKER!sw C/0 KLAGSBRUN EDELSTEIN BOSMAN DE VRIES INC. 220 Lange Street Nieuw Muckleneuk PRETORIA Tel: 012 452 8900 Fax: 012 452 8901 e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] (REF: HUGO STRUWIG I VS I HS000056) 599 3 TO: THE REGISTRAR OF THE GAUTENG DIVISION, PRETORIA AND TO: THE STATE ATTORNEY PRETORIA The First, Second and Third Respondents' Attorneys SALU Building 316 Thabo Sehume Street Pretoria Ref: 7641/2016/Z49 Tel: 012 309 1520 Fax: 086 507 0909 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Enq: J Meier (082 940 3938 AND TO: THE STATE ATTORNEY CAPE TOWN The Fourth and Fifth Respondents' Attorneys 22 Long Street Cape Town E-mail: [email protected] 600 4 6oo AND TO: WEBBER WENTZEL Sixth Respondent's Attorneys 90 Rivonia Road.