Mugger Crocodile Crocodylus Palustris Anslem Da Silva1 and Janaki Lenin2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Environmental DNA to Detect Estuarine Crocodiles, a Cryptic

Human–Wildlife Interactions 14(1):64–72, Spring 2020 • digitalcommons.usu.edu/hwi Using environmental DNA to detect estuarine crocodiles, a cryptic-ambush predator of humans Alea Rose, Research Institute for Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Northern Territory 0909, Australia Yusuke Fukuda, Department of Environment & Natural Resources, Northern Territory Govern- ment, P.O. Box 496, Palmerston, Northern Territory 0831, Australia Hamish A. Campbell, Research Institute of Livelihoods and the Environment, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Northern Territory 0909, Australia [email protected] Abstract: Negative human–wildlife interactions can be better managed by early detection of the wildlife species involved. However, many animals that pose a threat to humans are highly cryptic, and detecting their presence before the interaction occurs can be challenging. We describe a method whereby the presence of the estuarine crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), a cryptic and potentially dangerous predator of humans, was detected using traces of DNA shed into the water, known as environmental DNA (eDNA). The estuarine crocodile is present in waterways throughout southeast Asia and Oceania and has been responsible for >1,000 attacks upon humans in the past decade. A critical factor in the crocodile’s capability to attack humans is their ability to remain hidden in turbid waters for extended periods, ambushing humans that enter the water or undertake activities around the waterline. In northern Australia, we sampled water from aquariums where crocodiles were present or absent, and we were able to discriminate the presence of estuarine crocodile from the freshwater crocodile (C. johnstoni), a closely related sympatric species that does not pose a threat to humans. -

IATTC-94-01 the Tuna Fishery, Stocks, and Ecosystem in the Eastern

INTER-AMERICAN TROPICAL TUNA COMMISSION 94TH MEETING Bilbao, Spain 22-26 July 2019 DOCUMENT IATTC-94-01 REPORT ON THE TUNA FISHERY, STOCKS, AND ECOSYSTEM IN THE EASTERN PACIFIC OCEAN IN 2018 A. The fishery for tunas and billfishes in the eastern Pacific Ocean ....................................................... 3 B. Yellowfin tuna ................................................................................................................................... 50 C. Skipjack tuna ..................................................................................................................................... 58 D. Bigeye tuna ........................................................................................................................................ 64 E. Pacific bluefin tuna ............................................................................................................................ 72 F. Albacore tuna .................................................................................................................................... 76 G. Swordfish ........................................................................................................................................... 82 H. Blue marlin ........................................................................................................................................ 85 I. Striped marlin .................................................................................................................................... 86 J. Sailfish -

Nile Crocodile Fact Sheet 2017

NILE CROCODILE FACT SHEET 2017 Common Name: Nile crocodile Order: Crocodylia Family: Crocodylidae Genus & Species: Crocodylus niloticus Status: IUCN Least Concern; CITES Appendix I and II depending on country Range: The Nile crocodile is found along the Nile River Valley in Egypt and Sudan and distributed throughout most of sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar. Habitat: Nile crocodiles occupy a variety of aquatic habitats including large freshwater lakes, rivers, freshwater swamps, coastal estuaries, and mangrove swamps. In Gorongosa, Lake Urema and its network of rivers are home to a large crocodile population. Description: Crocodylus niloticus means "pebble worm of the Nile” referring to the long, bumpy appearance of a crocodile. Juvenile Nile crocodiles tend to be darker green to dark olive-brown in color, with blackish cross-banding on the body and tail. As they age, the banding fades. As adults, Nile crocodiles are a grey-olive color with a yellow belly. Their build is adapted for life in the water, having a streamlined body with a long, powerful tail, webbed hind feet and a long, narrow jaw. The eyes, ears, and nostrils are located on the top of the head so that they can submerge themselves under water, but still have sensing acuity when hunting. Crocodiles do not have lips to keep water out of their mouth, but rather a palatal valve at the back of their throat to prevent water from being swallowed. Nile crocodiles also have integumentary sense organs which appear as small pits all over their body. Organs located around the head help detect prey, while those located in other areas of the body may help detect changes in pressure or salinity. -

Master of the Marsh Information for Cart

Mighty MikeMighty Mike:Mike: The Master of the Marsh A story of when humans and predators meet Alligators are magnificent predators that have lived for millions of years and demonstrate amazing adaptations for survival. Their “recent” interaction with us demonstrates the importance of these animals and that we have a vital role to play in their survival. Primary Exhibit Themes: 1. American Alligators are an apex predator and a keystone species of wetland ecosystems throughout the southern US, such as the Everglades. 2. Alligators are an example of a conservation success story. 3. The wetlands that alligators call home are important ecosystems that are in need of protection. Primary Themes and Supporting Facts 1. Alligators are an apex predator and, thus, a keystone species of wetland ecosystems throughout the southern US, such as the Everglades. a. The American Alligator is known as the “Master of the Marsh” or “King of the Everglades” b. What makes a great predator? Muscles, Teeth, Strength & Speed i. Muscles 1. An alligator has the strongest known bite of any land animal – up to 2,100 pounds of pressure. 2. Most of the muscle in an alligators jaw is intended for biting and gripping prey. The muscles for opening their jaws are relatively weak. This is why an adult man can hold an alligators jaw shut with his bare hands. Don’t try this at home! ii. Teeth 1. Alligators have up to 80 teeth. 2. Their conical teeth are used for catching the prey, not tearing it apart. 3. They replace their teeth as they get worn and fall out. -

Crocodile Facts and Figures

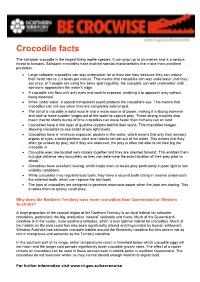

Crocodile facts The saltwater crocodile is the largest living reptile species. It can grow up to six metres and is a serious threat to humans. Saltwater crocodiles have evolved special characteristics that make them excellent predators. • Large saltwater crocodiles can stay underwater for at least one hour because they can reduce their heart rate to 2-3 beats per minute. This means that crocodiles can wait underwater until they see prey, or if people are using the same spot regularly, the crocodile can wait underwater until someone approaches the water’s edge. • A crocodile can float with only eyes and nostrils exposed, enabling it to approach prey without being detected. • When under water, a special transparent eyelid protects the crocodile’s eye. This means that crocodiles can still see when they are completely submerged. • The tail of a crocodile is solid muscle and a major source of power, making it a strong swimmer and able to make sudden lunges out of the water to capture prey. These strong muscles also mean that for shorts bursts of time crocodiles can move faster than humans can on land. • Crocodiles have a thin layer of guanine crystals behind their retina. This intensifies images, allowing crocodiles to see better at low light levels. • Crocodiles have a ‘minimum exposure’ posture in the water, which means that only their sensory organs of eyes, cranial platform, ears and nostrils remain out of the water. This means that they often go unseen by prey, but if they are observed, the prey is often not able to tell how big the crocodile is. -

Fascinating Folktales of Thailand

1. The rabbiT and The crocodile Once upon a time the rabbit used to have a long and beautiful tail similar to that of the squirrel and at that time the crocodile also had a long tongue like other animals on earth. Unfortunately, one day while the rabbit was drinking water at the bank of a river without realizing possible danger, a big crocodile slowly and quietly moved in. It came close to the poor rabbit. The crocodile suddenly snatched the small creature into its mouth with intention of eating it slowly. However, before swallowing its prey, the crocodile threatened the helpless rabbit by making a loud noise without opening its mouth. Afraid as it was, the rabbit pretended not to fear approaching death and shouted loudly. “A poor crocodile! Though you are big, I’m not afraid of you in the least. You threatened me with a noise not loud enough to make me scared because you didn’t open your mouth widely.” Not knowing the rabbit’s trick, the furious crocodile opened its mouth widely and made a loud noise. As soon as the crocodile opened its mouth, the rabbit jumped out fast and its sharp claws snatched away the crocodile’s tongue. At the moment of sharp pain, the crocodile shut its mouth at once as instinct had taught it to do. At the end of the episode, the rabbit lost its beautiful tail while the crocodile lost its long tongue in exchange for its ignorance of the trick. From then on, the rabbit no longer had a long tail while the crocodile no longer had a long tongue as other animals. -

European Bison

IUCN/Species Survival Commission Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is one of six volunteer commissions of IUCN – The World Conservation Union, a union of sovereign states, government agencies and non- governmental organisations. IUCN has three basic conservation objectives: to secure the conservation of nature, and especially of biological diversity, as an essential foundation for the future; to ensure that where the Earth’s natural resources are used this is done in a wise, European Bison equitable and sustainable way; and to guide the development of human communities towards ways of life that are both of good quality and in enduring harmony with other components of the biosphere. A volunteer network comprised of some 8,000 scientists, field researchers, government officials Edited by Zdzis³aw Pucek and conservation leaders from nearly every country of the world, the SSC membership is an Compiled by Zdzis³aw Pucek, Irina P. Belousova, unmatched source of information about biological diversity and its conservation. As such, SSC Ma³gorzata Krasiñska, Zbigniew A. Krasiñski and Wanda Olech members provide technical and scientific counsel for conservation projects throughout the world and serve as resources to governments, international conventions and conservation organisations. IUCN/SSC Action Plans assess the conservation status of species and their habitats, and specifies conservation priorities. The series is one of the world’s most authoritative sources of species conservation information -

Using Scat to Estimate Body Size in Crocodilians: Case Studies of the Siamese Crocodile and American Alligator with Practical Applications

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 15(2):325–334. Submitted: 19 December 2019; Accepted: 24 May 2020; Published: 31 August 2020. USING SCAT TO ESTIMATE BODY SIZE IN CROCODILIANS: CASE STUDIES OF THE SIAMESE CROCODILE AND AMERICAN ALLIGATOR WITH PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS STEVEN G. PLATT1, RUTH M. ELSEY2, NICHOLE D. BISHOP3, THOMAS R. RAINWATER4,8, OUDOMXAY THONGSAVATH5, DIDIER LABARRE6, AND ALEXANDER G. K. MCWILLIAM5,7 1Wildlife Conservation Society-Myanmar Program, No. 12, Nanrattaw Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon, Myanmar 2Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge, 5476 Grand Chenier Highway, Grand Chenier, Louisiana 70643, USA 3School of Natural Resources and Environment, Building 810, 1728 McCarthy Drive, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611-0485, USA 4Tom Yawkey Wildlife Center & Belle W. Baruch Institute of Coastal Ecology and Forest Science, Clemson University, Post Office Box 596, Georgetown, South Carolina 29442, USA 5Wildlife Conservation Society-Lao Program, Post Office Box 6712, Vientiane, Laos 6Départment de Biologie, Faculté des Sciences, Université de Sherbrooke, 2500 Boulevard de l’Université, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada 7Current address: International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), 63 Sukhumvit Road, Soi 39 Klongton-Nua, Bangkok, Thailand, 10110 8Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract.—Models relating morphological measures to body size are of great value in crocodilian research and management. Although scat morphometrics are widely used for estimating the body size of large mammals, these relationships have not been determined for any crocodilian. To this end, we collected scats from Siamese Crocodiles (Crocodylus siamensis) and American Alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) to determine if maximum scat diameter (MSD) could be used to predict total length (TL) in these species. -

Fish, Amphibians, and Reptiles)

6-3.1 Compare the characteristic structures of invertebrate animals... and vertebrate animals (fish, amphibians, and reptiles). Also covers: 6-1.1, 6-1.2, 6-1.5, 6-3.2, 6-3.3 Fish, Amphibians, and Reptiles sections Can I find one? If you want to find a frog or salamander— 1 Chordates and Vertebrates two types of amphibians—visit a nearby Lab Endotherms and Exotherms pond or stream. By studying fish, amphib- 2 Fish ians, and reptiles, scientists can learn about a 3 Amphibians variety of vertebrate characteristics, includ- 4 Reptiles ing how these animals reproduce, develop, Lab Water Temperature and the and are classified. Respiration Rate of Fish Science Journal List two unique characteristics for Virtual Lab How are fish adapted each animal group you will be studying. to their environment? 220 Robert Lubeck/Animals Animals Start-Up Activities Fish, Amphibians, and Reptiles Make the following Foldable to help you organize Snake Hearing information about the animals you will be studying. How much do you know about reptiles? For example, do snakes have eyelids? Why do STEP 1 Fold one piece of paper lengthwise snakes flick their tongues in and out? How into thirds. can some snakes swallow animals that are larger than their own heads? Snakes don’t have ears, so how do they hear? In this lab, you will discover the answer to one of these questions. STEP 2 Fold the paper widthwise into fourths. 1. Hold a tuning fork by the stem and tap it on a hard piece of rubber, such as the sole of a shoe. -

1 19-01 Misc Recommendation by Iccat on Fishes Considered to Be Tuna and Tuna-Like Species Or Oceanic, Pelagic, and Highly

19-01 MISC RECOMMENDATION BY ICCAT ON FISHES CONSIDERED TO BE TUNA AND TUNA-LIKE SPECIES OR OCEANIC, PELAGIC, AND HIGHLY MIGRATORY ELASMOBRANCHS RECALLING the work of the Working Group on Convention Amendment to clarify the scope of the Convention through the development of proposed amendments to the Convention; FURTHER RECALLING that the proposed amendments developed by the Working Group on Convention Amendment included defining “ICCAT species” to include tuna and tuna-like fishes and elasmobranchs that are oceanic, pelagic, and highly migratory; NOTING the work of the Standing Committee on Research and Statistics (SCRS) to determine which modern taxonomic groupings correspond to the definition of “tuna and tuna-like fishes” in Article IV of the Convention, and which elasmobranch species would be considered “oceanic, pelagic, and highly migratory”; THE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION FOR THE CONSERVATION OF ATLANTIC TUNAS (ICCAT) RECOMMENDS THAT: 1. Upon the entry into force of the amendments to the Convention as developed by the Working Group on Convention Amendment, the term “tuna and tuna-like fishes” shall be understood to include the species of the family Scombridae, with the exception of the genus Scomber, and the sub-order Xiphioidei. 2. Upon the entry into force of the amendments to the Convention as developed by the Working Group on Convention Amendment, the term “elasmobranchs that are oceanic, pelagic, and highly migratory” shall be understood to include the species as follows: Orectolobiformes Rhincodontidae Rhincodon typus (Smith -

Identification Notes &~@~-/~: ~~*~@~,~ 'PTILE

CATEGORY Identification Notes &~@~-/~: ~~*~@~,~ ‘PTILE for wildlife law enforcement ~ C.rnrn.n N.rn./s: Al@~O~, c~~~dil., ~i~.xl, Gharial PROBLEM: Skulls of Crocodilians are often imported as souvenirs. nalch (-”W 4(JI -“by ieeth ??la&ularJy+i9 GUIDE TO PRELIMINARY IDENTIFICATION OF CROCODILL4N SKULLS 1. Nasal bones separated from nasal aperture; mandibular symphysis extends to the 15th tooth. 2. Gavialis gangeticus Nasal bones entering the nasal aperture; mandibular symphysisdoes not extend beyond the8th tooth . Tomistoma schlegelii 2. Nasal bones separated from premaxillary bones; 27 -29maxi11aryteeth,25 -26mandibularteeth Nasal bones in contact with premaxillaq bo Qoco@khs acutus teeth, 18-19 mandibular teeth . Tomiitomaschlegelii 3. Fourth mandibular tooth usually fitting into a notch in the maxilla~, 16-19 maxillary teeth, 14-15 mandibular teeth . .4 Osteolaemus temaspis Fourth mandibular tooth usually fitting into a pit in the maxilla~, 14-20 maxillary teeth, 17-22 mandibular teeth . .5 4. Nasal bones do not divide nasal aperture. .. CrocodylW (12 species) Alligator m&siss@piensh Nasalboncx divide nasal aperture . Osteolaemustetraspk. 5. Nasal bones do not divide nasal aperture. .6 . Paleosuchus mgonatus Bony septum divides nasal aperture . .. Alligator (2 species) 6. Fiveteethinpremaxilla~ bone . .7 . Melanosuchus niger Four teeth in premaxillary bone. ...Paleosuchus (2species) 7. Vomerexposed on the palate . Melanosuchusniger Caiman crocodiles Vomer not exposed on palate . ...”..Caiman (2species) Illustrations from: Moo~ C. C 1921 Me&m, F. 19S1 L-.. Submitted by: Stephen D. Busack, Chief, Morphology Section, National Fish& Wildlife Forensics LabDate submitted 6/3/91 Prepared in cooperation with the National Fkh & Wdlife Forensics Laboratoy, Ashlar@ OR, USA ‘—m More on reverse side>>> IDentMcation Notes CATEGORY: REPTILE for wildlife law enforcement -- Crocodylia II CAmmom Nda Alligator, Crocodile, Caiman, Gharial REFERENCES Medem, F. -

Surveying Death Roll Behavior Across Crocodylia

Ethology Ecology & Evolution ISSN: 0394-9370 (Print) 1828-7131 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/teee20 Surveying death roll behavior across Crocodylia Stephanie K. Drumheller, James Darlington & Kent A. Vliet To cite this article: Stephanie K. Drumheller, James Darlington & Kent A. Vliet (2019): Surveying death roll behavior across Crocodylia, Ethology Ecology & Evolution, DOI: 10.1080/03949370.2019.1592231 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03949370.2019.1592231 View supplementary material Published online: 15 Apr 2019. Submit your article to this journal View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=teee20 Ethology Ecology & Evolution, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1080/03949370.2019.1592231 Surveying death roll behavior across Crocodylia 1,* 2 3 STEPHANIE K. DRUMHELLER ,JAMES DARLINGTON and KENT A. VLIET 1Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, The University of Tennessee, 602 Strong Hall, 1621 Cumberland Avenue, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA 2The St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park, 999 Anastasia Boulevard, St. Augustine, FL 32080, USA 3Department of Biology, University of Florida, 208 Carr Hall, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA Received 11 December 2018, accepted 14 February 2019 The “death roll” is an iconic crocodylian behaviour, and yet it is documented in only a small number of species, all of which exhibit a generalist feeding ecology and skull ecomorphology. This has led to the interpretation that only generalist crocodylians can death roll, a pattern which has been used to inform studies of functional morphology and behaviour in the fossil record, especially regarding slender-snouted crocodylians and other taxa sharing this semi-aquatic ambush pre- dator body plan.