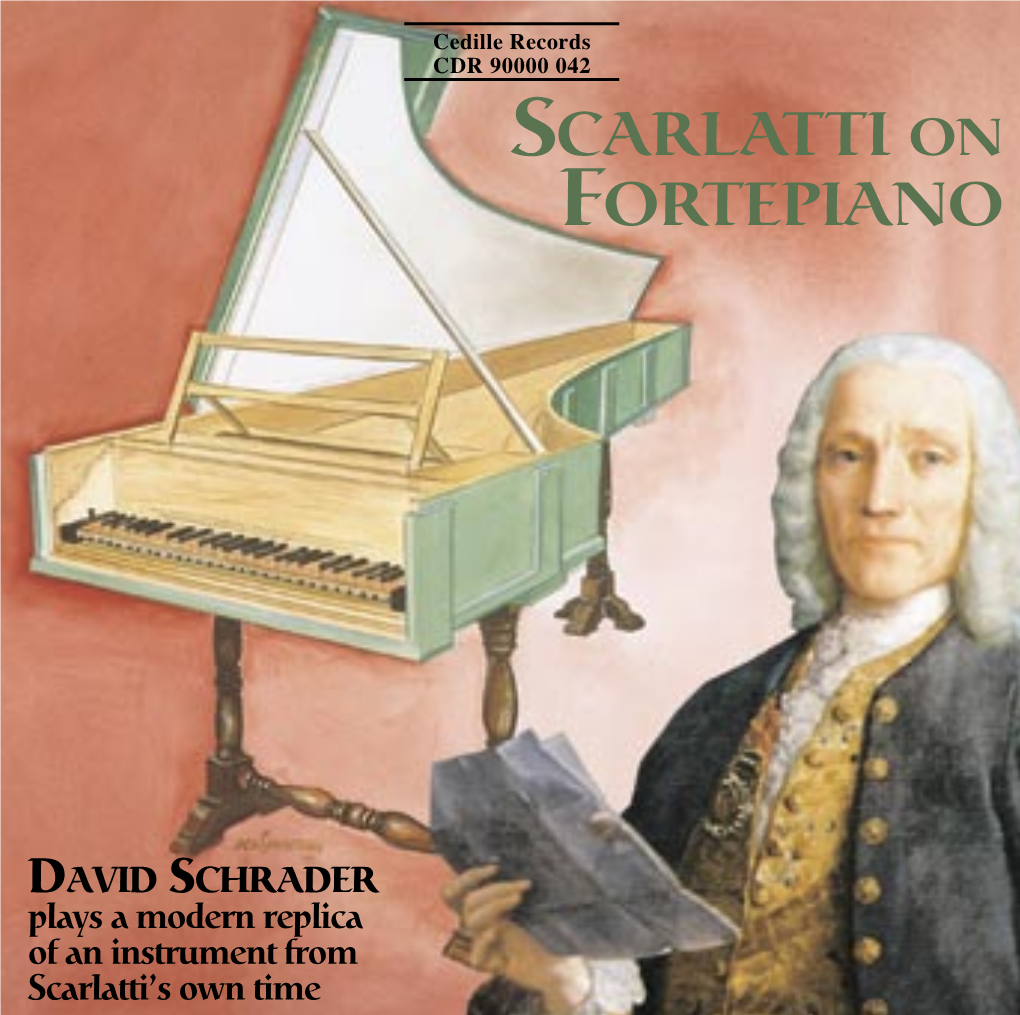

Scarlatti on Fortepiano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 VIOLIN SONATAS Federico Del Sordo FRANKFURT 1715 Harpsichord

Valerio Losito Baroque violin 6 VIOLIN SONATAS Federico Del Sordo FRANKFURT 1715 harpsichord Telemann GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN (1681–1767) Six Sonatas for Solo Violin, 1715 6 Sonatas ‘Frankfurt 1715’ for solo violin and harpsichord “My Lord, I am not without fear in dedicating these sonatas to Your Highness. It is, Sire, that without mentioning the vivacity of your sublime mind, you also have such certain taste in this fine art, which is the only one with the advantage of begin eternal, Sonata No.1 in G minor TWV41:g1 Sonata No.4 in G TWV41:G1 though it is very hard to create in a work worthy of your approbation. My Lord, I 1. Adagio 1’43 13. Largo 1’12 flatter myself that with this gift of the first pieces that I have had published you will 2. Allegro 2‘45 14. Allegro 2’18 find acceptable my intention of recognizing in some way the favour with which you 3. Adagio 1’08 15. Adagio 2’48 have hitherto honoured me. If, my Lord, my work is thus fortunate enough to meet 4. Vivace 3’03 16. Allegro 2’30 with your pleasure, then I am assured of the support of all connoisseurs, because no one can hope to achieve such understanding as yours. The beauty of the Concertos Sonata No.2 in D TWV41:D1 Sonata No.5 in A minor TWV41:a1 that you yourself have written at such a young age is admired by all those who have 5. Allemanda, Largo 3’52 17. Allemanda, Largo 2’37 seen them, and this is a guarantee for me in my aim. -

The Double Keyboard Concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

The double keyboard concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Waterman, Muriel Moore, 1923- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 18:28:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318085 THE DOUBLE KEYBOARD CONCERTOS OF CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH by Muriel Moore Waterman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: JAMES R. -

NOVEMBER 2020 COMPLIMENTARY GUIDE Catskillregionguide.Com

Catskill Mountain Region NOVEMBER 2020 COMPLIMENTARY GUIDE catskillregionguide.com WELCOME HOME TO THE CATSKILL MOUNTAINS! With a Special Section: Visit Woodstock November 2020 • GUIDE 1 2 • www.catskillregionguide.com IN THIS ISSUE www.catskillregionguide.com VOLUME 35, NUMBER 11 November 2020 PUBLISHERS Peter Finn, Chairman, Catskill Mountain Foundation Sarah Finn, President, Catskill Mountain Foundation EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, CATSKILL MOUNTAIN FOUNDATION Sarah Taft ADVERTISING SALES Barbara Cobb Steve Friedman CONTRIBUTING WRITERS & ARTISTS Benedetta Barbaro, Darla Bjork, Rita Gentile, Liz Innvar, Joan Oldknow, Jeff Senterman, Sarah Taft, Margaret Donsbach Tomlinson & Robert Tomlinson ADMINISTRATION & FINANCE Candy McKee On the cover: The Ashokan Reservoir. Photo by Fran Driscoll, francisxdriscoll.com Justin McGowan & Emily Morse PRINTING Catskill Mountain Printing Services 4 A CATSKILLS WELCOME TO THE GRAF PIANO DISTRIBUTION By Joan Oldknow & Sarah Taft Catskill Mountain Foundation 12 ART & POETRY BY RITA GENTILE EDITORIAL DEADLINE FOR NEXT ISSUE: November 10 The Catskill Mountain Region Guide is published 12 times a year 13 TODAY BUILDS TOMORROW: by the Catskill Mountain Foundation, Inc., Main Street, PO Box How to Build the Future We Want: The Fear Factor 924, Hunter, NY 12442. If you have events or programs that you would like to have covered, please send them by e-mail to tafts@ By Robert Tomlinson catskillmtn.org. Please be sure to furnish a contact name and in- clude your address, telephone, fax, and e-mail information on all correspondence. For editorial and photo submission guidelines 14 VISIT WOODSTOCK send a request via e-mail to [email protected]. The liability of the publisher for any error for which it may be held legally responsible will not exceed the cost of space ordered WELCOME HOME TO THE CATSKILL MOUNTAINS! or occupied by the error. -

The Keyboad Sonatas of Domenico Scalatti and Eighteenth-Centuy Musical Style

THE KEYBOAD SONATAS OF DOMENICO SCALATTI AND EIGHTEENTH-CENTUY MUSICAL STYLE W. DEAN SUTCLIFFE St Catharine’sCollege, Cambridge published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2003 Thisbook isin copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Bembo 11/13 pt. System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 521 48140 6 hardback CONTENTS Preface page vii 1 Scarlatti the Interesting Historical Figure 1 2 Panorama 26 Place and treatment in history 26 The dearth of hard facts29 Creative environment 32 Real-life personality 34 The panorama tradition 36 Analysis of sonatas 38 Improvisation 40 Pedagogy 41 Chronology 43 Organology 45 Style classification 49 Style sources 54 Influence 55 Nationalism I 57 Nationalism II 61 Evidence old and new 68 3 Heteroglossia 78 An open invitation to the ear: topic and genre 78 A love-hate relationship? -

Soler Quintets with David Schrader on Cedille Records Soler: Quintets for Harpsichord and Strings Nos

DDD Absolutely Digital CDR 90000 030 FIRST TIME ON CD PADRE ANTONIO SOLER (1729-1783) QUINTETS FOR HARPSICHORD & STRINGS Quintet No. 4 in A Minor (23:39) 1 I. Allegretto (6:13) 2 II. Minuetto I & II (2:49) 3 III. Allegro assai (5:40) 4 IV. Minuetto con variazioni (8:48) Quintet No. 5 in D Major (28:30) 5 I. Cantabile (6:59) 6 II. Allegro Presto (5:48) 7 III. Minuetto & Quartetto (5:23) 8 IV. Rondo. Allegretto (10:11) Quintet No. 6 in G Minor (22:27) 9 I. Andante (4:55) 10 II. Minuetto (6:37) 11 III. Rondo. Andante con moto (10:48) David Schrader, harpsichord Chicago Baroque Ensemble TT: (74:57) Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not- for-profit foundation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation’s activities are partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. The Keyboard Quintets of Soler Antonio Francisco Javier Jose Soler still recognized as valid, it is well to note y Ramos was baptized on December that the modulations were considered 3, 1729. Destined for a career in the radical enough in eighteenth century church, in 1736 he entered the choir Spain to elicit critical rebuttal, to which school of the great Catalan monastery Soler himself responded with a 1765 of Montserrat, where he studied with tract entitled Satisfacción a los reparos the monastery’s Maestro, Benito Esteve, precisos (reply to specific objections). and its organist, Benito Valls. -

The Program E E

W the program E E 24 K june RISING STAR SERIES 4 y a d s Daria Rabotkina, piano e u T 8 PM “FLOW MY TEARES” (1600) John Dowland (1563-1626)/arr. Daria Rabotkina SONATA IN E MAJOR, K. 162 (1756-57) Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757) Andante—Allegro—Andante—Allegro SELECTIONS FROM ORDRE 18ÈME DE CLAVECIN IN F MAJOR (1722) François Couperin (1668-1733) ITALIAN CONCERTO, BWV 971 ( ca . 1735) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) [without tempo designation] Andante Presto :: intermission :: SONATINE (1903-05) Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Modéré Mouvement de menuet Animé SONATA NO. 3 IN A MINOR FOR PIANO, OP. 28 (1917) Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) Allegro tempestoso—Moderato—Allegro tempestoso—Moderato—Più lento—Più animato—Allegro I—Poco più mosso FANTASY SUITE AFTER BIZET’S CARMEN , 1ST MOVEMENT Sergei Rabotkin (b. 1953) This concert is made possible in part through the generosity of Pat Petrou. Ms. Rabotkina is a winner of the Concert Artists Guild International Competition and is represented by Concert Artists Guild. concertartists.org 33RD SEASON | ROCKPORT MUSIC :: 51 “FLOW MY TEARES” John Dowland (b. London, 1563; d. London, February 20, 1626)/arr. Daria Rabotkina Composed 1600 Non otthees program In addition to wide-ranging “traditional” piano repertoire, Daria Rabotkina has acquired a substantial store of piano works borrowed and adapted from far-flung places in the music by world, including her own concert arrangement* of ragtime legend “Luckey” Roberts’s “Pork Sandra Hyslop and Beans.” As the opening offering on this evening’s concert—in contrast to the fantasy on Bizet’s stormy opera Carmen with which she closes—Ms. -

The Lute's Influence on Seventeenth-Century Harpsichord

Audrey S. Rutt 12 April 2017 A BLEND OF TRADITIONS: THE LUTE’S INFLUENCE ON SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY HARPSICHORD REPERTOIRE The Harpsichord ◦ Mechanically, a hybrid instrument ◦ Like the organ: ◦ chromatic keyboard with one pitch per key ◦ well-suited for polyphony and accompaniment ◦ Like the lute: ◦ plucked string instrument ◦ must account for quick sound decay by forms of arpeggiation ◦ Existent by the fifteenth century ◦ Not widely manufactured until the sixteenth century The Organ’s Influence ◦ The early harpsichord style was not distinct from the organ’s ◦ Pieces not designated specifically for either keyboard instrument ◦ Early works were simply transcriptions of vocal or ensemble pieces ◦ Obras de musica para tecla, arpa, y vihuela (Antonio Cabezón, 1510-1566) ◦ vocal transciptions arranged generally for polyphonic string instruments ◦ The broadness of this collection could include the harp, the Spanish vihuela, and the keyboard ◦ suggests that “the stringed keyboard instruments had not developed enough of a basic style to warrant independent compositions of their own” ◦ Early harpsichord composers were also organists, so idioms of the organ tradition were assumed The Organ Tradition ◦ For many centuries, the primary keyboard instrument ◦ Robertsbridge Codex (1320) is first example of newly-composed repertoire but follows vocal tradition closely ◦ Development of a true organ style ◦ Conrad Paumann (1410-1473), Paul Hofhaimer (1459-1537), Andrea Gabrieli (1533-1585) ◦ Fundamentum organisandi ◦ used florid, rhythmically varying upper -

There Isn't a Piece That Doesn't Impress. This Is As

Also by Trio Settecento on Cedille Records An Italian Soujourn CDR 90000 099 “There isn’t a piece that doesn’t impress. This is as good a collection for a newcomer to the Baroque as it is for those who want to hear these works performed at a high level.” — Gramophone Producer: James Ginsburg Schmelzer) / Louis Begin, replica of 18th Century model (rest of program) Trio Settecento A German Bouquet Engineer: Bill Maylone Bass Viola da Gamba: William Turner, Art Direction: Adam Fleishman / 1 Johann Schop (d. 1667): Nobleman (1:56) bm Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) London, 1650 Fugue in G minor, BWV 1026 (3:54) www.adamfleishman.com 2 Johann Heinrich Schmelzer (c. 1620–1680) ’Cello: Unknown Tyrolean maker, 18th Cover Painting: Still Life with a Wan’li Sonata in D minor (5:49) Philipp Heinrich Erlebach (1657–1714) century (Piesendel) Sonata No. 3 in A Major (14:06) Vase of Flowers (oil on copper), Georg Muffat (1653–1704) Bosschaert, Ambrosius the Elder (1573- Viola da Gamba and ’Cello Bow: Julian Sonata in D major (11:33) bn I. Adagio—Allegro—Lento (2:35) 1621) / Private Collection / Johnny Van Clarke bo II. Allemande (2:19) 3 I. Adagio (2:34) Haeften Ltd., London / The Bridgeman bp III. Courante (1:33) Harpsichord: Willard Martin, Bethlehem, 4 II. Allegro—Adagio—Allegro—Adagio (8:59) Art Library bq IV. Sarabande (1:53) Pennsylvania, 1997. Single-manual Johann Philipp Krieger (1649–1725) br V. Ciaconne (3:42) Recorded June 16, 17, 19, 23, and 24, instrument after a concept by Marin Sonata in D Minor Op. -

Programme Note ANETA MARKUSZEWSKA

Programme note ANETA MARKUSZEWSKA Following the death of John III and a failed attempt by the Sobieski dynasty to retain the crown, Marie Casimire decided to leave the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and make her way to Rome. She arrived in the Eternal City in March 1699, after a journey lasting almost half a year. The official reason for her arrival in the city was the jubilee year 1700, celebrated in the capital of Christianity with great pomp. In the end the Widow-Queen remained in Rome for fifteen years. Marie Casimire soon became known as an esteemed patron of music. Her residence in the Palazzo Zuccari in Trinità de’ Monti (next to the Spanish Steps, which did not yet exist) was a venue for renditions of commemorative cantatas and serenatas celebrating the memory of her distinguished husband, as well as performances of improvised comedies and dance. In 1709 Marie Casimire Sobieski organised in her palace a private opera theatre, where operas to librettos by Carlo Sigismondo Capece with music by the young Domenico Scarlatti were staged until 1714. One of the works presented at the time was the dramma per musica Tolomeo e Alessandro, ovvero la corona disprezzata by Capece-Scarlatti. The opera had its premiere on 17th January 1711. About the performance an anonymous chronicler wrote: ‘On Monday evening in her residence on Trinità de’ Monti, the Queen of Poland opened performances of an opera featuring female singers and good musicians [instrumentalists] which was generally acknowledged as superior to others.’ In a letter to her eldest son Jakub Sobieski, who was staying in Oława, Marie Casimire related that: ‘the whole work was composed in three weeks . -

A Consonance-Based Approach to the Harpsichord Tuning of Domenico Scarlatti John Sankey 1369 Matheson Road, Gloucester, Ontario K1J 8B5, Canada William A

A consonance-based approach to the harpsichord tuning of Domenico Scarlatti John Sankey 1369 Matheson Road, Gloucester, Ontario K1J 8B5, Canada William A. Sethares University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin 53706-1691 ~Received 16 August 1995; revised 28 October 1996; accepted 29 October 1996! This paper discusses a quantitative method for the study of historical keyboard instrument tunings that is based on a measure of the perceived dissonance of the intervals in a tuning and their frequency of occurrence in the compositions of Domenico Scarlatti ~1685–1757!. We conclude that the total dissonance of a large volume of music is a useful tool for studies of keyboard instrument tuning in a historical musical context, although it is insufficient by itself. Its use provides significant evidence that Scarlatti used French tunings of his period during the composition of his sonatas. Use of total dissonance to optimize a 12-tone tuning for a historical body of music can produce musically valuable results, but must at present be tempered with musical judgment, in particular to prevent overspecialization of the intervals. © 1997 Acoustical Society of America. @S0001-4966~97!03603-5# PACS numbers: 43.75.Bc @WJS# INTRODUCTION particularly uncertain, since he was born and trained in Italy, but spent most of his career in Portugal and Spain, and did Numerous musical scales have been used over the years all of his significant composing while clearly under strong for Western music, with the aim of maximizing the quality of Spanish influence. A method which might infer information sound produced by fixed-pitch 12-note instruments such as concerning his tuning preferences solely from his surviving the harpsichord. -

Piano History

ABOUT THE PIANO A SHORT HISTORY OF THE PIANO If you have ever played a harpsichord or a clavichord, you know they feel dif- ferent from a piano. In a piano, a hammer is thrown at the strings when you press a key on the keyboard. The hammer quickly rebounds so the string can vi- brate for as long as you hold the key down (or even longer if you use the damper pedal). The harpsichord is different because the strings are plucked by a plectrum (originally the pointed end of a feather, now made of plastic or other synthetic material). Because the harpsichord plucks the string (as opposed to a hammer striking the string), you are very conscious of the moment the plucking takes place. The clavichord strikes the string with a metal tangent. Unlike the piano’s ham- mer that rebounds right away, the tangent stays in contact with the string. So the clavichord, too, has its own feel. A keyboard instrument called a virginal was a small and simple rectangular form of the harpsichord. The spinet was another small harpsichord-type instru- ment. These are some of the earliest keyboard instruments. Even the fortepiano, the name given to the earliest piano to distinguish it from the modern pianoforte, or piano, has its own feel—the depth of the key fall is shallow and it takes much less weight to press the key down. THE CRISTOFORI PIANOFORTE The piano itself was invented in Italy in 1709 by Bartolommeo Cristofori. His was a four-octave instrument (compared to our seven-and-a half-octave modern instrument), with hammers striking the strings just as they do on a modern pi- ano. -

On National Influence in the Keyboard Works of Domenico Scarlatti

Scarlatti and the Spanish Body: On National Influence in the Keyboard Works of Domenico Scarlatti Sara Gross Modern scholars, lacking biographic details and autograph sources, know relatively little about Domenico Scarlatti and the background of his works for keyboard. This absence of information often results in contradictory accounts and even myths in musicological scholarship on the composer.1 Born in 1685 in Naples, Scarlatti spent nearly half of his life in Italy composing opera and half of his life writing keyboard works on the Iberian Peninsula, working as a keyboard teacher and composer for Doña María Bárbara de Braganza (first a Princess of Portugal and later, Queen of Spain). Given the composer’s bipartite life, Scarlatti is claimed at once by Italian musicologists as an integral figure in the canon of Italian musicians,2 while Spaniards, including the composer Manuel de Falla, have placed Scarlatti instead within a long lineage of Spanish composers and performers. It would appear, however, that despite nationalist boundaries and historical vagaries that frustrate the present field, all Scarlatti scholars find themselves in agreement upon one point: that he was among the finest keyboard composer-virtuosos of the era, a status owing entirely to Scarlatti’s seemingly 1 Little biographical detail remains from either his life in Italy or on the Iberian peninsula and earnest searches have, as yet, failed to uncover any original manuscripts or autographs of the keyboard sonatas that comprise the vast majority of Scarlatti’s work. 2 Gian Francisco Malipiero names Scarlatti the “last heir in the great Italian school issuing from Palestrina, Gesualdo da Venosa, Girolamo Frescobaldi, and Claudio Monteverdi” in “Domenico Scarlatti,” The Musical Quarterly 13 (1927): 485.