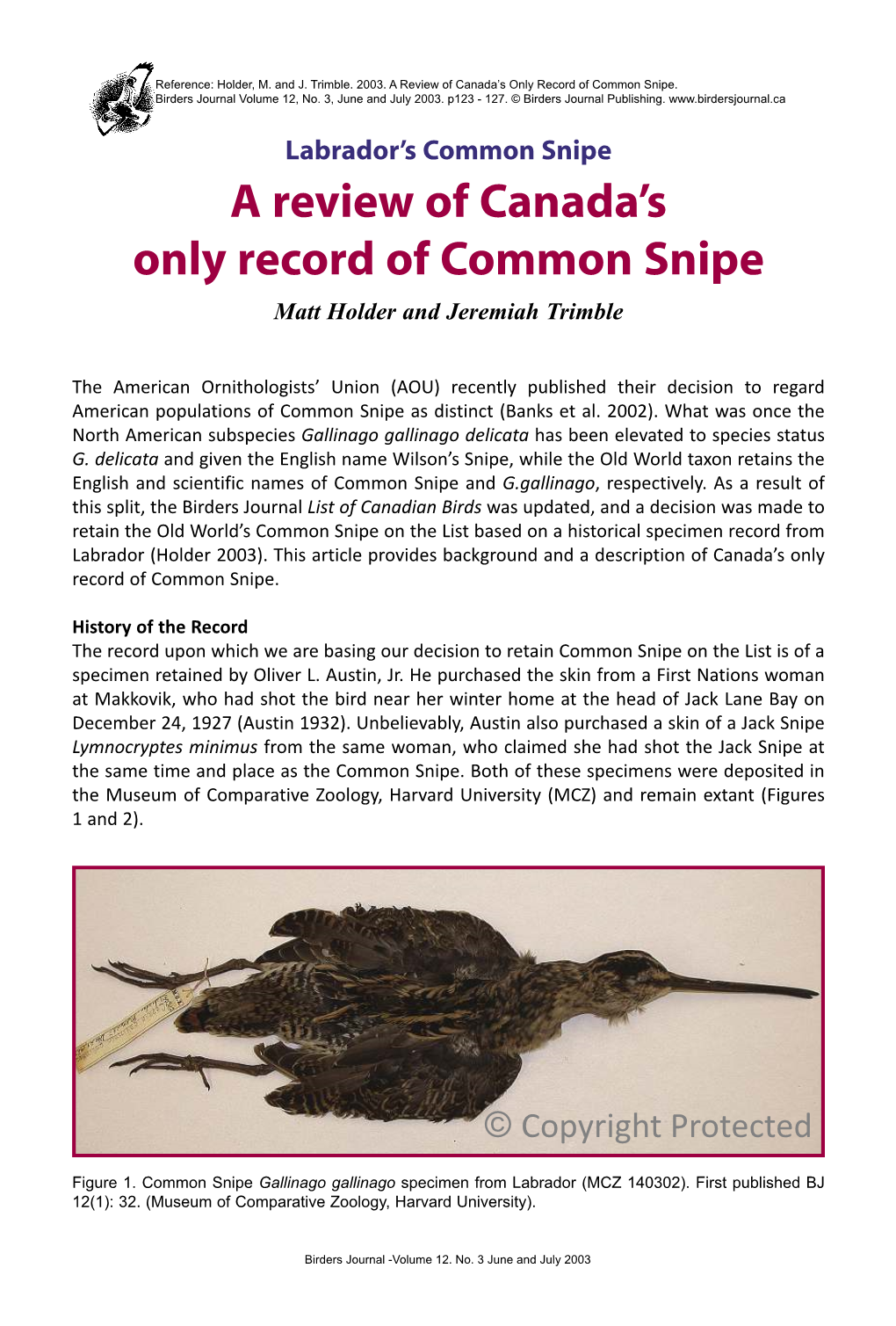

Areviewofcanada's Onlyrecordofcommonsnipe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Studies Overview

Chapter 7. Bird Studies Overview teigerwald Lake National Wildlife Refuge provides a variety of habitats for many species of birds. Thousands of breeding birds rely on the resources of the refuge to Srest, eat, and raise their young. In addition, the refuge supports wetlands that are vital to the survival of migratory birds. The activities that follow offer an excellent opportunity for students to learn about and to observe the different species of birds — their behaviors and adaptations to the habitats on the refuge. Background The actively managed refuge wetlands and grasslands, when combined with the natural floodplain vegetative communities, provide habitat that supports over 200 species of birds. Hundreds of thousands of birds migrate along the lower Columbia River every year. The refuge hosts thousands of migratory birds that fly thousands of miles from their breeding grounds in Arctic Canada and Alaska to their wintering grounds in Baja California or South America, a route known as the Pacific Flyway. The few remaining areas of wetland habitat along the lower Columbia River are vital to the flyway. Some birds spend their winter on refuge wetlands, returning north to nest; some nest here but migrate to milder climates in the south for the winter; and some do not migrate at all but remain in the area as permanent residents. Several of the songbirds found in the summer spend our winters in Central and South America, migrating thousands of miles annually between their summer and winter habitats. Birds using the refuge are specifically adapted to the type of food they eat and the type of habitat they occupy (open water, freshwater wetland, field, riparian woodland, or upland woodland). -

Migration Phenology of Jack Snipe Lymnocryptes Minimus at an Irish Coastal Wetland

Migration phenology of Jack Snipe Lymnocryptes minimus at an Irish coastal wetland Tom Cooney 42 All Saint’s Road, Raheny, Dublin D05 C627 Corresponding author: [email protected] Keywords: Ireland, Jack Snipe, Lymnocryptes minimus , migration phenology Migration times of Jack Snipe Lymnocryptes minimus were monitored at North Bull Island in Dublin Bay during 2011/2012 to 2016/2017. Average arrival times in autumn centred on 2 October and average departure times in spring on 23 April. Although these results were site and habitat specific, they were similar to recent migration data for Ireland. While the time series examined for Ireland and Britain were of different lengths, migration times were extraordinarily similar. The average autumn arrival date for Ireland as a whole was 16 September while that for Britain was 23 September, and departure times in spring for Ireland centred on 30 April, one day later than in Britain. The close agreement suggests that migration times across both islands possibly occur synchronously. Other recently generated data for Ireland provides tantalising evidence that passage migration may take place and that Jack Snipe could be more frequent in upland areas than previously suspected. In both instances greater clarity will only be possible through increased observer effort and higher detection rates of this enigmatic species. Introduction Britain, but not in Ireland (Smiddy 2002). In winter, Jack Snipe appear to be widely but thinly distributed across much of Jack Snipe Lymnocryptes minimus are difficult to detect in Ireland with highest densities in counties along the west coast winter largely due to their solitary behaviour, nocturnal or (Balmer et al. -

03/16/2020 9:21 Am

ACTION: Withdraw Proposed DATE: 03/16/2020 9:21 AM 1501:31-7-05 Seasons and limits on rail, common snipe (Wilson's snipe), woodcock, gallinules (common moorhens), teal, geese and mourning doves. (A) Throughout the state, it shall be unlawful for any person to hunt, kill, wound, take, or attempt to take, or to possess any of the migratory game birds specified in this rule except as provided in this rule or other rules of the Administrative Code. (1) It shall be unlawful for any person to hunt, take, or possess any rails except sora and Virginia, which may be hunted and taken from September 1, 20192020 through November 9, 20192020. (2) It shall be unlawful for any person to take or possess more than twenty-five rails singly or in the aggregate in one day, or to possess more than seventy-five rails singly or in the aggregate at anytime after the second day. (3) It shall be unlawful for any person to hunt, take, or possess common snipe (Wilson's snipe) at any time, except from September 1, 20192020 through November 26, 201924, 2020 and December 14, 201912, 2020 through January 2December 31, 2020. (4) It shall be unlawful for any person to hunt, take, or possess woodcock at any time, except from October 12, 201910, 2020 through November 25, 201923, 2020. (5) It shall be unlawful for any person to hunt or take rails, common snipe (Wilson's snipe), woodcock, or gallinules (common moorhens) at any time, except from sunrise to sunset daily during the open season. -

The Birds of Wimbledon Common and Putney Heath 2015

The Birds of Wimbledon Common and Putney Heath 2015 Male Wheatear on the log pile 1 The Birds of Wimbledon Common and Putney Heath 2015 The Birds of Wimbledon Common and Putney Heath 2015 espite coverage on the Common being rather poor again this year, a total of 96 species were D recorded, four more than in 2014. Of these, 45 bred or probably bred, with no doubt the highlight of the year being the successful breeding of a pair of Skylarks on the Plain, the first to do so since 2007. Much credit for this achievement must go to Wildlife & Conservation Officer, Peter Haldane, and his staff, who have persevered over the years to create a suitable and safe habitat for this Red-listed bird. Credit is also due to Chief Executive, Simon Lee, for his valuable cooperation, and indeed to the vast majority of the visiting public, many of whom have displayed a keen interest in the well-being of these iconic birds. Signage on the Plain this year was extended to the two uncut sections during the autumn and winter months, thus affording our migrants and winter-visiting birds a sanctuary in which to feed and shelter safely. Another outstanding high note this year was the Snow Bunting found on the Large Mound in January, a first for the Common since records began in 1974; and yet another first for the Common came in the form of three Whooper Swans at Rushmere in December. There was also a surprising influx of Lesser Spotted Woodpeckers during the spring, a bird that in the previous few years had become an extremely scarce visitor. -

Cranial Pneumatization Patterns and Bursa of Fabricius in North American Shorebirds

CRANIAL PNEUMATIZATION PATTERNS AND BURSA OF FABRICIUS IN NORTH AMERICAN SHOREBIRDS RAYIUOND MCNEIL AND JEAN BURTON study of age criteria in some species of North American shorebirds A brought us to consider two of the best known techniques of age deter- mination in birds, the size of the bursa of Fabricius and the degrees and pat- terns of skull pneumatization. The only attempt, known to us, to correlate bursa of Fabricius and gonadal development with the ossification of the skull is that of Davis (1947). The bursa of Fabricius is a lympho-epithelial organ lying dorsally above the cloaca. At least in some species it has an opening in the cloaca. It reaches its maximum size at 4-6 months and then begins involution (Davis, 1947). By cloaca1 examination of the bursal pouch, it is possible to distinguish juvenile from adult individuals of some taxa of birds especially Anseriformes and Galliformes (Gower, 1939; Hochbaum, 1942; Linduska, 1943; Kirkpatrick, 1944). Unfortunately, in shorebird species, the bursa of Fabricius has no cloaca1 opening and thus cannot be used as an age criterion of living birds. The pneumatization of the skull has been used as a criterion for estimating the age of birds by C. L. Brehm as far back as 1822 (Niethammer, 1968)) but it was not generally used until the turn of the century (Serventy et al., 1967). Miller (1946) describes the skull ossification process as follows: “The skull of a passerine bird when it leaves the nest is made of a single layer of bone in the area overlaying the brain; at least, the covering appears single when viewed mac- roscopically. -

The Effects of Upland Management Practices on Avian Diversity

The Effects of Upland Management Practices on Avian diversity Bronwen Daniel September 2010 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science and the Diploma of Imperial College London 1 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Background................................................................................................................................. 11 2.1 Birds as indicators ................................................................................................................ 11 2.1.1 Upland birds ...................................................................................................................... 11 2.2 Management Practices......................................................................................................... 13 2.2.1 Grouse Moor Management........................................................................................... 15 2.2.2 Predator control ............................................................................................................ 16 2.2.3 Burning .......................................................................................................................... 17 2.2.4 Grazing Pressure............................................................................................................ 17 2.2.5 Implications of upland management for bird populations .......................................... -

Survival Rates of Russian Woodcocks

Proceedings of an International Symposium of the Wetlands International Woodcock and Snipe Specialist Group Survival rates of Russian Woodcocks Isabelle Bauthian, Museum national d’histoire naturelle, Centre de recherches sur la biologie des populations d’oiseaux, 55 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France. E-mail: [email protected] Ivan Iljinsky, State University of St Petersburg, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Sergei Fokin, State Informational-Analytical Center of Game Animals and Environment Group. Woodcock, Teterinsky Lane, 18, build. 8, 109004 Moscow, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Romain Julliard, Museum national d’histoire naturelle, Centre de recherches sur la biologie des populations d’oiseaux, 55 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France. E-mail: [email protected] François Gossmann, Office national de la chasse et de la faune sauvage, 53 rue Russeil, 44 000 Nantes, France. E-mail: [email protected] Yves Ferrand, Office national de la chasse et de la faune sauvage, BP 20 - 78612 Le-Perray-en-Yvelines Cedex, France. E-mail: [email protected] We analysed 324 recoveries from 2,817 Russian Woodcocks ringed as adult or yearling in two areas in Russia (Moscow and St Petersburg). We suspected that birds belonging to these two areas may experience different hunting pressure or climatic conditions, and thus exhibit different demographic parameters. To test this hypothesis, we analysed spatial and temporal distribution of recoveries, and performed a ringing-recovery analysis to estimate possible survival differences between these two areas. We used methods developed by Brownie et al. in 1985. We found differences in temporal variations of the age ratio between the two ringing areas. -

Wilson's Snipe

Wilson’s Snipe (Gallinago delicate) Torrey Wenger Monroe Co., MI. 4/10/2007 © Allen Chartier (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) Wilson’s Snipe is a victim of the lumpers and dwelling sandpiper was reported in 23% of Michigan’s townships; in MBBA II, they were splitters. In 1945, Wilson’s Snipe was reported in only 14.5%, a drop of nearly 40%. combined with other snipe species worldwide as The most significant decrease occurred in the the Common Snipe, Gallinago gallinago (AOU SLP: Wilson’s Snipe were found in almost 60% 1945). In 2002, based on behavioral and fewer townships and were not found in 14 structural differences, it was split off again counties where they were previously (Banks et al. 2002). While this frustrates casual documented. birders and competitive listers alike, the bird itself certainly does not care. This on-again, Some of this decline may be caused by observer off-again status is not the origin of the infamous bias. First, snipe are most detectable during “snipe hunt”, where children are sent into the their early mating season, as males make bushes searching for a non-existent bird. “winnowing” flights above their territories – if observers delayed the start of their fieldwork, All snipe feed by using their long bills to probe they missed this species. Second, the snipe is a for small insects and larvae in mud and moist habitat specialist, preferring wetlands with low soils. A snipe can open just the tip of its bill, herbaceous vegetation, sparse shrubs, and enabling it to capture and swallow small prey scattered trees (Mueller 1999) – if observers items without removing its bill from the soil. -

HANDBOOK 2018 Taking a Look Back! the First South Dakota Pheasant Hunting Season Was a One-Day Hunt Held in Spink County on October 3O, 1919

Hunting and trapping HANDBOOK 2018 Taking a look back! The first South Dakota pheasant hunting season was a one-day hunt held in Spink County on October 3O, 1919. Help the South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks tip our blaze orange caps to the past 100 years of Outdoor Tradition, and start celebrating the next century. Show us how you are joining in on the fun by using #MySDTradition when sharing all your South Dakota experiences. Look to the past, and step into the future with South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks. Photo: South Dakota State Historical Society SOUTH DAKOTA GAME, FISH & PARKS HUNTING HANDBOOK CONSERVATION OFFICER DISTRICTS GENERAL INFORMATION: 605.223.7660 TTY: 605.223.7684, email: [email protected] Aberdeen: 605.626.2391, 5850 E. Hwy 12 Pierre: 605.773.3387, 523 E. Capitol Ave. Chamberlain: 605.734.4530, 1550 E. King Ave. Rapid City: 605.394.2391, 4130 Adventure Trail Ft. Pierre: 605.223.7700, 20641 SD Hwy 1806 Sioux Falls: 605.362.2700, 4500 S. Oxbow Ave. Huron: 605.353.7145, 895 3rd Street SW Watertown: 605.882.5200, 400 West Kemp Mobridge: 605.845.7814, 909 Lake Front Drive Webster: 605.345.3381, 603 E. 8th Ave. CONSERVATION OFFICERS *denotes District Conservation Officer Supervisor Martin Tom Beck 605.381.6433 Britton Casey Dowler 605.881.3775 Hill City Jeff Edwards 605.381.9995 Webster Austin Norton 605.881.2177 Hot Springs D.J. Schroeder 605.381.6438 Sisseton Dean Shultz 605.881.3773 Custer Ron Tietsort 605.431.7048 Webster Michael Undlin 605.237.3275 Spearfish Brian Meiers* 605.391.6023 Aberdeen Tim McCurdy* 605.380.4572 -

(2007): Birds of the Aleutian Islands, Alaska Please

Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi OSPREYS FINCHES Osprey Ca Ca Ac Brambling I Ca Ca EAGLES and HAWKS Hawfinch I Ca Northern Harrier I I I Common Rosefinch Ca Eurasian Sparrowhawk Ac (Ac) Pine Grosbeak Ca Bald Eagle* C C C C Asian Rosy-Finch Ac Rough-legged Hawk Ac Ca Ca Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch* C C C C OWLS (griseonucha) Snowy Owl I Ca I I Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch (littoralis) Ac Short-eared Owl* R R R U Oriental Greenfinch Ca FALCONS Common Redpoll I Ca I I Eurasian Kestrel Ac Ac Hoary Redpoll Ca Ac Ca Ca Merlin Ca I Red Crossbill Ac Gyrfalcon* R R R R White-winged Crossbill Ac Peregrine Falcon* (pealei) U U C U Pine Siskin I Ac I SHRIKES LONGSPURS and SNOW BUNTINGS Northern Shrike Ca Ca Ca Lapland Longspur* Ac-C C C-Ac Ac CROWS and JAYS Snow Bunting* C C C C Common Raven* C C C C McKay's Bunting Ca Ac LARKS EMBERIZIDS Sky Lark Ca Ac Rustic Bunting Ca Ca SWALLOWS American Tree Sparrow Ac Tree Swallow Ca Ca Ac Savannah Sparrow Ca Ca Ca Bank Swallow Ac Ca Ca Song Sparrow* C C C C Cliff Swallow Ca Golden-crowned Sparrow Ac Ac Barn Swallow Ca Dark-eyed Junco Ac WRENS BLACKBIRDS Pacific Wren* C C C U Rusty Blackbird Ac LEAF WARBLERS WOOD-WARBLERS Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi Wood Warbler Ac Yellow Warbler Ac Dusky Warbler Ac Blackpoll Warbler Ac DUCKS, GEESE and SWANS Kamchatka Leaf Warbler Ac Yellow-rumped Warbler Ac Emperor Goose C-I Ca I-C C OLD WORLD FLYCATCHERS "HYPOTHETICAL" species needing more documentation Snow Goose Ac Ac Gray-streaked Flycatcher Ca American Golden-plover (Ac) Greater White-fronted Goose I -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Checklist of the Birds of Shetland by Hugh Harrop & Rob Fray

Checklist of the Birds of Shetland by Hugh Harrop & Rob Fray This checklist covers the birds recorded in the county of Shetland up until 15 June 2008. Each species is categorised, depending on the criteria for its admission to the Shetland list. Species in category D or category E do not form part of the main list. The definitions of each category are: Category A = species which have been recorded in an apparently wild state at least once since 1 January 1958. Category B = species which were recorded in an apparently wild state at least once up to 31 December 1957. Category C = species which, although introduced by man, have now established a regular feral breeding stock which apparently maintains itself without necessary recourse to further introduction. There are currently only two species in this category on the Shetland list - Mandarin Aix galericulata and Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis. None have been introduced to or bred in Shetland, but breed widely on the British mainland. They are all vagrants to Shetland in a sense but have undoubtedly originated from British breeding stock. Category D = species which would otherwise appear in categories A, B or C except that: (D1) there is a reasonable doubt that they have ever occurred in a wild state; (D2) they have certainly arrived with a combination of ship and human assistance, including provision of food and shelter; (D3) they have only ever been found dead on the tideline; (D4) they would otherwise appear in category C, except that their feral populations may or may not be self-supporting.