Why Mysore? the Idealistic and Materialistic Factors Behind Tipu Sultan’S War Rocket Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report

Karnataka Tourism Vision group 2014 report KARNATAKA TOURISM VISION GROUP (KTVG) Recommendations to the GoK: Jan 2014 Task force KTVG Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report 1 FOREWORD Tourism matters. As highlighted in the UN WTO 2013 report, Tourism can account for 9% of GDP (direct, indirect and induced), 1 in 11 jobs and 6% of world exports. We are all aware of amazing tourist experiences globally and the impact of the sector on the economy of countries. Karnataka needs to think big, think like a Nation-State if it is to forge ahead to realise its immense tourism potential. The State is blessed with natural and historical advantage, which coupled with a strong arts and culture ethos, can be leveraged to great advantage. If Karnataka can get its Tourism strategy (and brand promise) right and focus on promotion and excellence in providing a wholesome tourist experience, we believe that it can be among the best destinations in the world. The impact on job creation (we estimate 4.3 million over the next decade) and economic gain (Rs. 85,000 crores) is reason enough for us to pay serious attention to focus on the Tourism sector. The Government of Karnataka had set up a Tourism Vision group in Oct 2013 consisting of eminent citizens and domain specialists to advise the government on the way ahead for the Tourism sector. In this exercise, we had active cooperation from the Hon. Minister of Tourism, Mr. R.V. Deshpande; Tourism Secretary, Mr. Arvind Jadhav; Tourism Director, Ms. Satyavathi and their team. The Vision group of over 50 individuals met jointly in over 7 sessions during Oct-Dec 2013. -

PART 1 of Volume 13:6 June 2013

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 13:6 June 2013 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. Assistant Managing Editor: Swarna Thirumalai, M.A. Contents Drama in Indian Writing in English - Tradition and Modernity ... 1-101 Dr. (Mrs.) N. Velmani Reflection of the Struggle for a Just Society in Selected Poems of Niyi Osundare and Mildred Kiconco Barya ... Febisola Olowolayemo Bright, M.A. 102-119 Identity Crisis in Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake ... Anita Sharma, M.Phil., NET, Ph.D. Research Scholar 120-125 A Textual Study of Context of Personal Pronouns and Adverbs in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” ... Fadi Butrus K Habash, M.A. 126-146 Crude Oil Price Behavior and Its Impact on Macroeconomic Variable: A Case of Inflation ... M. Anandan, S. Ramaswamy and S. Sridhar 147-161 Using Exact Formant Structure of Persian Vowels as a Cue for Forensic Speaker Recognition ... Mojtaba Namvar Fargi, Shahla Sharifi, Mohammad Reza Pahlavan-Nezhad, Azam Estaji, and Mehi Meshkat Aldini Ferdowsi University of Mashhad 162-181 Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 13:6 June 2013 Contents List i Simplification of CC Sequence of Loan Words in Sylheti Bangla ... Arpita Goswami, Ph.D. Research Scholar 182-191 Impact of Class on Life A Marxist Study of Thomas Hardy’s Novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles .. -

LORD WELLESLEY and HIS REFORMS Unit Structure

UNIT 6: LORD WELLESLEY AND HIS REFORMS Unit Structure 6.1 Learning Objectives 6.2 Introduction 6.3 Subsidiary Alliance 6.3.1 Merits 6.3.2 Demerits 6.4 Wellesley and the French Menace 6.5 Estimate of Lord Wellesley 6.6 Let Us Sum Up 6.7 Further Reading 6.8 Answers to Check Your Progress 6.9 Model Questions 6.2 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: After going through this unit you will be able to- Understand the Subsidiary Alliance, Analyse the merits and demerits of Subsidiary Alliance, Analyse Wellesley’s policies towards French in India, Estimate Lord Wellesley. 6.3 INTRODUCTION Lord Wellesley, better known as Marquess Wellesley appointed as Governor General of India in 1798. He had a clear vision of the Mission before him. He wanted to make the Company the supreme power in India, to add to its territories and to reduce all the Indian states to a position of dependence on the Company. Wellesley gave up the policy of peace and non-intervention and inaugurated the policy of war and further wars. In this unit we shall discuss his policies in detail. 7 0 History (Block 1) Lord Wellesley and His Reforms Unit 6 6.3 SUBSIDIARY ALLIANCE Wellesley by nature was an expansionist governor general. To achieve this aim he adopted the policy of conquest and annexation of Indian States. He adopted a new policy of expansion known as Subsidiary Alliance to expand the British territory. According to this new expansionist policy, any native state which wanted British protection to secure their territory from their enemies or restoration of internal peace and order could make an alliance with the British. -

Preserving and Protecting Mysore Heritage Tmt

Session – I Preserving And Protecting Mysore Heritage Tmt. Neela Manjunath, Commissioner, Archaeology, Museums and Heritage Department, Bangalore. An introduction to Mysore Heritage Heritage Heritage is whatever we inherit from our predecessors Heritage can be identified as: Tangible Intangible Natural Heritage can be environmental, architectural and archaeological or culture related, it is not restricted to monuments alone Heritage building means a building possessing architectural, aesthetic, historic or cultural values which is identified by the heritage conservation expert committee An introduction to Mysore heritage Mysore was the capital of princely Mysore State till 1831. 99 Location Mysore is to the south-west of Bangalore at a distance of 139 Kms. and is well connected by rail and road. The city is 763 meters above MSL Princely Heritage City The city of Mysore has retained its special characteristics of a ‘native‘princely city. The city is a classic example of our architectural and cultural heritage. Princely Heritage City : The total harmony of buildings, sites, lakes, parks and open spaces of Mysore with the back drop of Chamundi hill adds to the attraction of this princely city. History of Mysore The Mysore Kingdom was a small feudatory of the Vijayanagara Empire until the emergence of Raja Wodeyar in 1578. He inherited the tradition of Vijayanagara after its fall in 1565 A.D. 100 History of Mysore - Dasara The Dasara festivities of Vijayanagara was started in the feudatory Mysore by Raja Wodeyar in 1610. Mysore witnessed an era of pomp and glory under the reign of the wodeyars and Tippu Sultan. Mysore witnessed an all round development under the visionary zeal of able Dewans. -

Registered Office Address: Mindtree Ltd, Global Village, RVCE Post, Mysore Road, Bengaluru-560059, Karnataka, India

Registered Office Address: Mindtree Ltd, Global Village, RVCE Post, Mysore Road, Bengaluru-560059, Karnataka, India. CIN: L72200KA1999PLC025564 E-mail: [email protected] Ref: MT/STAT/CS/20-21/02 April 14, 2020 BSE Limited National Stock Exchange of India Limited Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Exchange Plaza, Bandra Kurla Complex, Dalal Street, Mumbai 400 001 Bandra East, Mumbai 400 051 BSE: fax : 022 2272 3121/2041/ 61 NSE : fax: 022 2659 8237 / 38 Phone: 022-22721233/4 Phone: (022) 2659 8235 / 36 email: [email protected] email : [email protected] Dear Sirs, Sub: Reconciliation of Share Capital Audit Report for the quarter ended March 31, 2020 Kindly find enclosed the Reconciliation of Share Capital Audit Certificate for the quarter ended March 31, 2020 issued by Practicing Company Secretary under Regulation 76 of the SEBI (Depositories and Participants) Regulations, 2018. Please take the above intimation on records. Thanking you, Yours sincerely, for Mindtree Limited Vedavalli S Company Secretary Mindtree Ltd Global Village RVCE Post, Mysore Road Bengaluru – 560059 T +9180 6706 4000 F +9180 6706 4100 W: www.mindtree.com · G.SHANKER PRASAD ACS ACMA PRACTISING COMPANY SECRETARY # 10, AG’s Colony, Anandnagar, Bangalore-560 024, Tel: 42146796 e-mail: [email protected] RECONCILIATION OF SHARE CAPITAL AUDIT REPORT (As per Regulation 76 of SEBI (Depositories & Participants) Regulations, 2018) 1 For the Quarter Ended March 31, 2020 2 ISIN INE018I01017 3 Face Value per Share Rs.10/- 4 Name of the Company MINDTREE LIMITED 5 Registered Office Address Global Village, RVCE Post, Mysore Road, Bengaluru – 560 059. 6 Correspondence Address Global Village, RVCE Post, Mysore Road, Bengaluru – 560 059. -

Of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN

Page 1 of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR_SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN REG_NUM QUALIF MOBILE EMAIL 7356 1994S 2091 345 28.04.49 KRISHNAMSETY D-12, IVRI, QTRS, HEBBAL, KARNATAKA VCI/85/94 B.V.Sc./APAU/ PRABHODAS BANGALORE-580024 KARNATAKA 8992 1994S 3750 425 03.01.43 SATYA NARAYAN SAHA IVRI PO HA FARM BANGALORE- KARNATAKA VCI/92/94 B.V.Sc. & 24 KARNATAKA A.H./CU/66 6466 1994S 1188 295 DINTARAN PAL ANIMAL NUTRITION DIV NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2150/91 BVSc & 9480613205 [email protected] ADUGODI HOSUR ROAD AH/BCKVV/91 BANGALORE 560030 KARNATAKA 7200 1994S 1931 337 KAJAL SANKAR ROY SCIENTIST (SS) NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2254/93 BVSc&AH/BCKVV/93 9448974024 [email protected] ADNGODI BANGLORE 560030 m KARNATAKA 12229 1995 2593 488 26.08.39 KRISHNAMURTHY.R,S/ #1645, 19TH CROSS 7TH KARNATAKA APSVC/205/94,VCI/61 BVSC/UNI OF 080 25721645 krishnamurthy.rayakot O VEERASWAMY SECTOR, 3RD MAIN HSR 7/95 MADRAS/62 09480258795 [email protected] NAIDU LAYOUT, BANGALORE-560 102. 14837 1995 5242 626 SADASHIV M. MUDLAJE FARMS BALNAD KARNATAKA KAESVC/805/ BVSC/UAS VILLAGE UJRRHADE PUTTUR BANGALORE/69 DA KA KARANATAKA 11694 1995 2049 460 29/04/69 JAMBAGI ADIGANGA EXTENSION AREA KARNATAKA 591220 KARNATAKA/2417/ BVSC&AH 9448187670 shekharjambagi@gmai RAJASHEKHAR A/P. HARUGERI BELGAUM l.com BALAKRISHNA 591220 KARANATAKA 10289 1995 624 386 BASAVARAJA REDDY HUKKERI, BELGAUM DISTT. KARNATAKA KARSUL/437/ B.V.SC./GAS 9241059098 A.I. KARANATAKA BANGALORE/73 14212 1995 4605 592 25/07/68 RAJASHEKAR D PATIL, AMALZARI PO, BILIGI TQ, KARNATAKA KARSV/2824/ B.V.SC/UAS S/O DONKANAGOUDA BIJAPUR DT. -

Anglo-Mysore War

www.gradeup.co Read Important Medieval History Notes based on Mysore from Hyder Ali to Tipu Sultan. We have published various articles on General Awareness for Defence Exams. Important Medieval History Notes: Anglo-Mysore War Hyder Ali • The state of Mysore rose to prominence in the politics of South India under the leadership of Hyder Ali. • In 1761 he became the de facto ruler of Mysore. • The war of successions in Karnataka and Haiderabad, the conflict of the English and the French in the South and the defeat of the Marathas in the Third battle of Panipat (1761) helped him in attending and consolidating the territory of Mysore. • Hyder Ali was defeated by Maratha Peshwa Madhav Rao in 1764 and forced to sign a treaty in 1765. • He surrendered him a part of his territory and also agreed to pay rupees twenty-eight lakhs per annum. • The Nizam of Haiderabad did not act alone but preferred to act in league with the English which resulted in the first Anglo-Mysore War. Tipu Sultan • Tipu Sultan succeeded Hyder Ali in 1785 and fought against British in III and IV Mysore wars. • He brought great changes in the administrative system. • He introduced modern industries by bringing foreign experts and extending state support to many industries. • He sent his ambassadors to many countries for establishing foreign trade links. He introduced new system of coinage, new scales of weight and new calendar. • Tipu Sultan organized the infantry on the European lines and tried to build the modern navy. • Planted a ‘tree of liberty’ at Srirangapatnam and -

Anglo-Mysore Wars

ANGLO-MYSORE WARS The Anglo-Mysore Wars were a series of four wars between the British and the Kingdom of Mysore in the latter half of the 18th century in Southern India. Hyder Ali (1721 – 1782) • Started his career as a soldier in the Mysore Army. • Soon rose to prominence in the army owing to his military skills. • He was made the Dalavayi (commander-in-chief), and later the Chief Minister of the Mysore state under KrishnarajaWodeyar II, ruler of Mysore. • Through his administrative prowess and military skills, he became the de- facto ruler of Mysore with the real king reduced to a titular head only. • He set up a modern army and trained them along European lines. First Anglo-Mysore War (1767 – 1769) Causes of the war: • Hyder Ali built a strong army and annexed many regions in the South including Bidnur, Canara, Sera, Malabar and Sunda. • He also took French support in training his army. • This alarmed the British. Course of the war: • The British, along with the Marathas and the Nizam of Hyderabad declared war on Mysore. • Hyder Ali was able to bring the Marathas and the Nizam to his side with skillful diplomacy. • But the British under General Smith defeated Ali in 1767. • His son Tipu Sultan advanced towards Madras against the English. Result of the war: • In 1769, the Treaty of Madras was signed which brought an end to the war. • The conquered territories were restored to each other. • It was also agreed upon that they would help each other in case of a foreign attack. -

Mehendale Book-10418

Tipu as He Really Was Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale Tipu as He Really Was Copyright © Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale First Edition : April, 2018 Type Setting and Layout : Mrs. Rohini R. Ambudkar III Preface Tipu is an object of reverence in Pakistan; naturally so, as he lived and died for Islam. A Street in Islamabad (Rawalpindi) is named after him. A missile developed by Pakistan bears his name. Even in India there is no lack of his admirers. Recently the Government of Karnataka decided to celebrate his birth anniversary, a decision which generated considerable opposition. While the official line was that Tipu was a freedom fighter, a liberal, tolerant and enlightened ruler, its opponents accused that he was a bigot, a mass murderer, a rapist. This book is written to show him as he really was. To state it briefly: If Tipu would have been allowed to have his way, most probably, there would have been, besides an East and a West Pakistan, a South Pakistan as well. At the least there would have been a refractory state like the Nizam's. His suppression in 1792, and ultimate destruction in 1799, had therefore a profound impact on the history of India. There is a class of historians who, for a long time, are portraying Tipu as a benevolent ruler. To counter them I can do no better than to follow Dr. R. C. Majumdar: “This … tendency”, he writes, “to make history the vehicle of certain definite political, social and economic ideas, which reign supreme in each country for the time being, is like a cloud, at present no bigger than a man's hand, but which may soon grow in volume, and overcast the sky, covering the light of the world by an impenetrable gloom. -

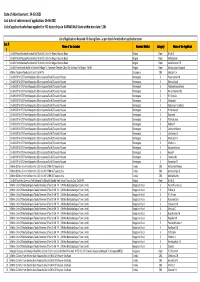

18.06.21.Final List of Applicants.Xlsx

Date of Advertisement : 24-03-2021 Last date of submission of application: 16-06-2021 List of applicants who have applied for RO dealerships in KARNATAKA State within due date: 1264 List of Applications Received till closing Date - as per details furnished on application cover Loc.N Name of the Location Revenue District Category Name of the Applicant ooo 1 On LHS From Mezban Function Hall To Indal Circle On Belgavi Bauxite Road Belgavi Open Girish D 1 On LHS From Mezban Function Hall To Indal Circle On Belgavi Bauxite Road Belgavi Open Ambikadevi G 1 On LHS From Mezban Function Hall To Indal Circle On Belgavi Bauxite Road Belgavi Open Sureshkumar R R 2 On LHS From Kerala Hotel In Biranholi Village To Hanuman Temple ,Ukkad On Kolhapur To Belgavi - NH48 Belgavi Open Mrutyunjaya Yaragatti 3 Within Tanigere Panchayath Limit On SH 76 Davangere OBC Santosh G H 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC Pavan kumar M 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC Dhana Gopal 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC Prabhakaravardhana 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC Narasimhamurthy 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC B V Srinivas 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC Chalapathi 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards Mysore Ramnagara SC Subramani Giridhar S 4 On LHS Of NH275 From -

Near-Death Experiences in South India: a Systematic Survey in Channapatna

Article NIMHANS Journal Near-Death Experiences in South India: A Systematic Survey in Channapatna Volume: 10 Issue: 02 July 1992 Page: 111-118 Satwant Pasricha, - Department of Clinical Psychology, National Institute of Mental Health & Neuro Sciences, Bangalore 560 029, India Abstract The study of unusual experiences of persons who survive death (NDE) has attracted the attention of scientists over the past two decades. However, very few reports concerning the prevalence of NDEs are available. So far, only two reports of surveys of such experiences have been published; one from the United States of America and the other from India. In the present article, the author reports the findings of another survey of NDEs and conducted in a region of southern India. A population of 17192 persons was surveyed and 2439 respondents were interviewed for identification of NDE cases. Twenty-six persons were reported to have died and revived, 16 (62%) of these having had NDEs. Thus the prevalence rate of NDEs, was found to be approximately one in thousand persons. Except for one subject all the subjects had NDEs at home. The characteristics of the NDE cases identified during the survey are presented. Similarities and differences in features between subjects of the cases reported from India and the USA are discussed and possible interpretations offered. Key words - NDEs, Survey Some persons after recovering from a close encounter with death from illness or other life-threatening situations, report unusual affective, cognitive and seemingly transcendental experiences. These have been frequently referred to as "near-death experiences (NDEs)". In the past two decades a number of reports on NDEs have been published from the West [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6] as well as from India [7], [8], [9], [10]. -

A Liber Amicorum: Thomas Wälde

A Liber Amicorum: Thomas Wälde Law Beyond Conventional Thought "A Liber Amicorum: Thomas Wälde - Law Beyond Conventional Thought" Edited by Jacques Werner & Arif Hyder Ali Republished on OGEL and TDM with kind permission from CMP Publishing Ltd. Also available as download via http://www.ogel.org/liber-amicorum.asp or http://www.transnational-dispute-management.com/liber-amicorum.asp For more information about the catalogue of books and journals of CMP Publishing visit www.cmppublishing.com Thomas Wälde (1949–2008) A Liber Amicorum: Thomas Wälde Law Beyond Conventional Thought Edited by Jacques Werner & Arif Hyder Ali CAMERON MAY I N T E R N A T I O N A L L A W & P O L I C Y Copyright © CMP Publishing Cameron May is an imprint of CMP Publishing Ltd Published 2009 by CMP Publishing Ltd 13 Keepier Wharf, 12 Narrow Street, London E14 8DH, UK Tel: +44 (0) 20 7199 1640 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7504 8283 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cmppublishing.com All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.