Source Document Advocacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protocol Clarification Memorandum #3 For

Protocol Clarification Memorandum #3 for: HPTN 046: A PHASE III TRIAL TO DETERMINE THE EFFICACY AND SAFETY OF AN EXTENDED REGIMEN OF NEVERAPINE IN INFANTS BORN TO HIV-INFECTED WOMEN TO PREVENT VERTICAL HIV TRANSMISSION DURING BREAST-FEEDING, VERSION 3.0, DATED 26 SEPTMEBER 2007 DAIDS Document ID 10142 Clarification Memo Date: 23 November 2009 Summary of Revisions and Rationale In addition to the typical childhood illnesses specified in Section 7.0, the following childhood illnesses will not be reported as adverse events: infantile colic pain, oral thrush, gastrointestinal reflux and constipation. The exceptions are if these illnesses result in hospitalization or death. These illnesses will be recorded in participant source records and captured in the interim medical history and physical examination findings. Implementation The procedures clarified in this memorandum have been approved by the NIAID Medical Officer. IRB approval of this Clarification Memorandum is not required by the sponsor prior to implementation; however sites may submit it to the responsible IRBs/ECs for their information or, if required by the IRBs/ECs, for their approval prior to implementation. The modification included in this Clarification Memorandum will be incorporated into the next full protocol amendment. Text appearing below in bold will be added to the protocol. Section 7.0 Safety Monitoring and Adverse Event Reporting, paragraph nine. The following typical childhood illnesses will be recorded in participant source records and captured in the study database as interim medical history or physical examination findings, but will not be reported separately as adverse experiences: diaper rash, otitis media, infantile colic pain, oral thrush, gastrointestinal reflux, constipation and afebrile upper and lower respiratory tract infections including bronchiolitis. -

Breastfeeding and HIV Global Breastfeeding COLLECTIVE Breastfeeding Gives All Children the Healthiest Start in Life

Siphiwe Khumalo, 37, and her baby, Lundiwe. Siphiwe was already on life-long antiretroviral treatment when she became pregnant with Lundiwe. This is her fifth pregnancy— all of her previous babies died shortly after birth. Siphiwe suspects they died of AIDS-related illnesses, although at that time, she didn’t know her status and never got her babies tested. Lundiwe is a happy, healthy baby, always smiling and very curious. Immediately after birth, Lundiwe tested negative, to the joy of her mother. ADVOCACY BRIEF Breastfeeding and HIV GLOBAL BREASTFEEDING COLLECTIVE Breastfeeding gives all children the healthiest start in life. Breastfeeding promotes cognitive development and acts as a child’s first vaccine, giving babies everywhere a critical boost. It also reduces the burden of childhood and maternal illness, lowering health care costs and creating healthier families. Increasing breastfeeding worldwide would prevent more than 800,000 child deaths each year, particularly those associated with diarrhoea and pneumonia.1 Led by UNICEF and WHO, the Global Breastfeeding Collective is a partnership of more than 20 prominent international agencies calling on donors, policymakers, philanthropists and civil society to increase investment in breastfeeding worldwide. The Collective’s vision is a world in which all mothers have the technical, financial, emotional and public support they need to breastfeed. The Collective advocates for smart investments in breastfeeding programmes, assists policymakers and NGOs in implementing solutions, and galvanizes support to get real results to increase rates of breastfeeding, thereby benefiting mothers, children and nations. Adequate support from families, communities, health workers and society is important to make breastfeeding work for all mothers; and those living with HIV need even more support. -

Breastfeeding in the HIV Epidemic: a Midwife's Dilemma in International Work Jennifer Ellen Dohrn Columbia University School of Nursing, [email protected]

Online Journal of Health Ethics Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 2 Breastfeeding in the HIV Epidemic: A Midwife's Dilemma in International Work Jennifer Ellen Dohrn Columbia University School of Nursing, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/ojhe Recommended Citation Dohrn, J. E. (2005). Breastfeeding in the HIV Epidemic: A Midwife's Dilemma in International Work. Online Journal of Health Ethics, 2(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.18785/ojhe.0201.02 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Journal of Health Ethics by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Breastfeeding in the HIV Epidemic Breastfeeding in the HIV Epidemic: A Midwife's Dilemma in International Work Jennifer Ellen Dohrn, CNM, NP, MS Columbia University School of Nursing New York, NY Abstract As standards develop to reduce the maternal-to-child transmission of HIV, healthcare professionals need to evaluate recommendations in the context of culturally-accepted values for the populations to be served. Breastfeeding, a central value in South African families, carries the risk of transmission in mothers that are HIV+. A dilemma faced by international workers is the sharing of information that challenges culturally-accepted practices. A nurse-midwife working with HIV positive women during the childbearing cycle in the United States is expected to implement protocols to prevent transmission of the HIV virus to the newborn. These include administration of antiretroviral medications to the women during the pregnancy and labor, as well as the policy of no breastfeeding, since breast milk contains the HIV virus and can be a source of passing the infection to the baby. -

Pmct Training Curriculum

PREVENTION OF MOTHER-TO-CHILD TRANSMISSION OF HIV •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• i KENYA PMCT PROJECT PMCT TRAINING CURRICULUM Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV A short course for health workers providing PMTCT services in areas with limited resources and high HIV prevalence KENYA PMCT PROJECT • KENYA PMCT PROJECT • KENYA PMCT PROJECT PREVENTION OF MOTHER-TO-CHILD TRANSMISSION OF HIV ii •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• © Population Council 2002 Population Council Horizons Project PO Box 17643 Nairobi, Kenya tel: +254 2 713480 fax:+254 2 713479 email: [email protected] Web site: htpp://www.popcouncil.org and htpp://beta/pcnairobi This training manual has been developed by the Kenya PMCT Project (1999) This study was supported by the Horizons Programme. Horizons is funded by the US Agency for International Development, under the terms of HRN-A-00-97- 00012-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the US Agency for International Development. The Population Council is an international, non-profit, non-governmental institution that seeks to improve the well-being and reproductive health of current and future generations around the world and to help achieve a humane, equitable, and sustainable balance between people and resources. The Council conducts biomedical, social science and public health research and helps build research capacities in developing countries. Established in 1952, the Council is governed by an international board -

Voices & Choices

POSITIVEPOSITIVE WOMEN:WOMEN: voicesvoicesandand choiceschoices ZimbabweZimbabwe ReportReport AA projectproject ledled byby positivepositive womenwomen toto exploreexplore thethe impactimpact ofof HIVHIV onon theirtheir sexualsexual behaviourbehaviour, , well-beingwell-being andand reproductivereproductive rightsrights, , andand toto promotepromote improvementsimprovements inin policypolicy andand practicepractice InternationalInternational CommunityCommunity ofof WomenWomen livingliving withwith HIV/AIDSHIV/AIDS (ICW)(ICW) Positive Women: Voices and Choices Positive Women: Voices and Choices – Zimbabwe Report A project led by positive women to explore the impact of HIV on their sexual behaviour, well-being and reproductive rights, and to promote improvements in policy and practice by Rayah Feldman, Jo Manchester and Caroline Maposhere Positive Women: Voices & Choices Zimbabwe Report © International Community of Women living with HIV/AIDS June 2002 Positive Women: Voices and Choices – Zimbabwe Report A project led by positive women to explore the impact of HIV on their sexual behavour, well-being and reproductive rights, and to promote improvements in policy and practice Written by: Rayah Feldman, Jo Manchester and Caroline Maposhere The authors assert their moral rights in respect of this publication Published by the International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS Layout and design by Fontline Electronic Publishing, Harare, Zimbabwe Printed by Préci-ex, Les Pailles, Mauritius ISBN: 0-7974-2430-X iv Positive Women: Voices & Choices -

HIV and AIDS)

PS2008_006 V2014 Position Statement Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV and AIDS) Background The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) causes a condition that can be controlled, but not cured, with antiretroviral drugs. Alternative therapies, lifestyle changes and improved living conditions contribute to improved treatment outcomes. Untreated HIV progresses to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) within 5 to 15 years. Continued compliance with the use of antiretroviral drugs can slow the progression of HIV to a near halt and life expectancy can be significantly increased. People living with HIV can remain well and productive for many years, even in low-income countries. In some countries it has been accepted that HIV positive status is a chronic syndrome. However AIDS is still a major contributor to death and morbidity worldwide. It can be transmitted through unprotected sexual intercourse (vaginal or anal), oral sex with an infected person; transfusion of contaminated blood; and the sharing of contaminated needles, syringes or other sharp instruments. It may also be transmitted between a mother and her infant during pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding. Position ICM: Affirms that all women have the right to full information on avoiding HIV infection and AIDS, knowledge of their own HIV-status, and how to prevent HIV transmission from mother to child. Underlines that all HIV positive pregnant women have a right to access antiretroviral drugs for themselves and their newborns. Urges midwives, in their capacity as professionals and members of communities to be educators as well as practitioners in working to prevent the spread of HIV and provide care and treatment as it becomes available. -

HIV and Infant Feeding Guidelines for Decision-Makers

HIV and Infant Feeding Guidelines for decision-makers WHO/FRH/NUT/CHD/98.1 UNAIDS/98.3 UNICEF/PD/NUT/(J)98-1 Distrib.: General Original: English Reprinted with revisions, June 1998 ©World Health Organization 1998 ©Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 1998 This document is not a formal publication of the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNAIDS, but all rights are reserved by these agencies. The document may, however, be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced and transmitted, in part or in whole, but not for sale nor for use in conjunction with commercial purposes. For authorization to translate the work in full, and for any use by commercial entities, applications and enquiries should be addressed to the Programme of Nutrition, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, which will be glad to provide the latest information on any changes made to the text, plans for new editions, and the reprints and translations that are already available. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this work does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO and UNAIDS concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers' products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by WHO and UNAIDS in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary -

Bibliographical Title Page

Bibliographical Title Page HIV and AIDS Care Primary Health Care Initiatives (PHCI) Project Contract No. 278-C-00-99-00059-00 Abt Associates Inc. HIV and AIDS Care HIV and AIDS Care Table of Contents Page Definitions 184 How HIV is Contracted 185 How HIV is Not Contracted 185 Symptoms of HIV infection and AIDS 185 Who is at Risk? 186 Preventing HIV Infection 186 Breastfeeding for the HIV Positive Woman 187 Health Provider’s Role in HIV Prevention 189 STI and HIV Prevention Messages 189 List of Tables Page Table 1. HIV & Infant Feeding Counseling Guidelines in Low- 188 Resource Communities HIV and AIDS Care Definitions HIV Human immunodeficiency virus, the organism that causes AIDS. A person can be infected with HIV for many years and not know it. HIV is carried in the blood, semen, and vaginal secretions of infected persons. HIV can be passed on (transmitted) whether symptoms of AIDS are present or not. AIDS Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, a condition caused by HIV that attacks the body’s immune system and makes it unable to fight disease and infection that ultimately results in death. Antibody A protein produced in the blood to fight infection. At Risk People who practice behaviors that may result in becoming infected with HIV. For example, unprotected sex with persons who may be infected with HIV/AIDS and sharing of needles that have not been sterilized between uses. Condom A latex sheath used to cover the penis during intercourse to help prevent pregnancy and/or the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV. -

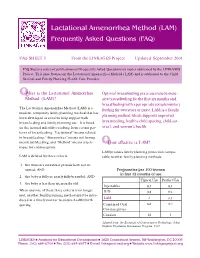

Lactational Amenorrhea Method (LAM) Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Lactational Amenorrhea Method (LAM) Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) FAQ SHEET 3 From the LINKAGES Project Updated September 2001 FAQ Sheet is a series of publications of Frequently Asked Questions on topics addressed by the LINKAGES Project. This issue focuses on the Lactational Amenorrhea Method (LAM) and is addressed to the Child Survival and Family Planning Health Care Provider. QWhat is the Lactational Amenorrhea Optimal breastfeeding practices include exclu- Method (LAM)? sive breastfeeding for the first six months and breastfeeding with appropriate complementary The Lactational Amenorrhea Method (LAM) is a feeding for two years or more. LAM is a family modern, temporary family planning method that has planning method which supports improved been developed as a tool to help support both breastfeeding and family planning use. It is based breastfeeding, healthy child spacing, child sur- on the natural infertility resulting from certain pat- vival, and women’s health. terns of breastfeeding. “Lactational” means related to breastfeeding; “Amenorrhea” means not having menstrual bleeding; and “Method” means a tech- QHow effective is LAM? nique for contraception. LAM provides family planning protection compa- LAM is defined by three criteria: rable to other family planning methods. 1. the woman’s menstrual periods have not re- sumed, AND Pregnancies per 100 women in first 12 months of use 2. the baby is fully or nearly fully breastfed, AND Typical Use Perfect Use 3. the baby is less than six months old. Injectables 0.3 0.3 When any one of these three criteria is no longer IUD 0.8 0.6 met, another family planning method must be intro- LAM 2 0.5 duced in a timely manner to ensure healthy birth spacing. -

Social Determinants of Breastfeeding Preferences Among Black Mothers Living with HIV in Two North American Cities

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Social Determinants of Breastfeeding Preferences among Black Mothers Living with HIV in Two North American Cities Josephine Etowa 1,*, Egbe Etowa 2, Hilary Nare 1,*, Ikenna Mbagwu 1 and Jean Hannan 3 1 School of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON K1N 6N5, Canada; [email protected] 2 Department of Sociology, Anthropology & Criminology, Faculty of Arts, Humanities & Social Sciences, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON N9B 3P4, Canada; [email protected] 3 Nicole Wertheim College of Nursing and Health Sciences, Academic Centre 3, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199, USA; jean.hannan@fiu.edu * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.E.); [email protected] (H.N.) Received: 16 August 2020; Accepted: 16 September 2020; Published: 21 September 2020 Abstract: The study is motivated by the need to understand the social determinants of breastfeeding attitudes among HIV-positive African, Caribbean, and Black (ACB) mothers. To address the central issue identified in this study, analysis was conducted with datasets from two North American cities, where unique country-specific guidelines complicate infant feeding discourse, decisions, and practices for HIV-positive mothers. These national infant feeding guidelines in Canada and the US present a source of conflict and tension for ACB mothers as they try to navigate the spaces between contradictory cultural expectations and national guidelines. Analyses in this paper were drawn from a broader mixed methods study guided by a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to examine infant feeding practices among HIV-positive Black mothers in three countries. The survey were distributed through Qualtrics and SPSS was used for data cleaning and analysis. -

Prevention of HIV-1 Transmission Through Breastfeeding

PREVENTION RESEARCH Prevention of HIV-1 Transmission Through Breastfeeding: Efficacy and Safety of Maternal Antiretroviral Therapy Versus Infant Nevirapine Prophylaxis for Duration of Breastfeeding in HIV-1-Infected Women With High CD4 Cell Count (IMPAACT PROMISE): A Randomized, Open-Label, Clinical Trial Patricia M. Flynn, MD,* Taha E. Taha, MD,† Mae Cababasay, MS,‡ Mary Glenn Fowler, MD,§ Lynne M. Mofenson, MD,k Maxensia Owor, MD,¶ Susan Fiscus, PhD,# Lynda Stranix-Chibanda, MD,** Anna Coutsoudis, PhD,†† Devasena Gnanashanmugam, MD,‡‡ Nahida Chakhtoura, MD,§§ Katie McCarthy, BS,kk Cornelius Mukuzunga, MD,¶¶ Bonus Makanani, MD,## Dhayendre Moodley, PhD,*** Teacler Nematadzira, MD,††† Bangini Kusakara, MD,††† Sandesh Patil, MD,‡‡‡ Tichaona Vhembo, MD,††† Raziya Bobat, MD,§§§ Blandina T. Mmbaga, MD,kkk Maysseb Masenya, MD,¶¶¶ Mandisa Nyati, MD,### Gerhard Theron, MD,**** Helen Mulenga, MD,†††† Kevin Butler, MS,‡ and David E. Shapiro, PhD,‡ the PROMISE Study Team Setting: Fourteen sites in Sub-Saharan Africa and India. Background: No randomized trial has directly compared the efficacy of prolonged infant antiretroviral prophylaxis versus Methods: A randomized, open-label strategy trial was conducted in maternal antiretroviral therapy (mART) for prevention of mother- HIV-1–infected women with CD4 counts $350 cells/mm3 (or to-child transmission throughout the breastfeeding period. $country-specific ART threshold if higher) and their breastfeeding Received for publication August 8, 2017; accepted November 12, 2017. From the *Department of Infectious -

HIV Transmission Through Breastfeeding, with a Focus on Information Made Available Between 2001 and 2007

This publication is an update of the review of current knowledge on HIV transmission through breastfeeding, with a focus on information made available between 2001 and 2007. It re- views scientific evidence on the risk of HIV transmission through breastfeeding, the impact of different feeding options on child health outcomes, and conceivable strategies to reduce HIV transmission through breastfeeding with an emphasis on the developing world. HIV Transmission Through Breastfeeding For further information, please contact: World Health Organization Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development ([email protected]) or Department of HIV/AIDS ([email protected]) or Department of Nutrition for Health and Development ([email protected]) 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland website: http://www.who.int UNICEF Nutrition Section – Programme Division 3 United Nations Plaza A REVIEW OF AVAILABLE EVIDENCE New York, New York 10017, United States of America 2007 Update Tel +1 212 326 7000 ISBN 978 92 4 159659 6 HIV Transmission Through Breastfeeding A Review of Available Evidence 2007 Update HIV TRANSMISSION THROUGH BREASTFEEDING: A REVIEW OF AVAILABLE EVIDENCE - AN UPDATE FROM 2001 TO 2007 WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data HIV transmission through breastfeeding : a review of available evidence : 2007 update. 1.HIV infections - transmission. 2.Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome - Transmission. 3.Breast feeding - adverse effects. 4.Disease transmission, Vertical - prevention and control 5.Review litera- ture. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 159659 6 (NLM classification: WC 503.3) © World Health Organization 2008 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]).