Sediment Samples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio In

microorganisms Review The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel disease Spase Stojanov 1,2, Aleš Berlec 1,2 and Borut Štrukelj 1,2,* 1 Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Ljubljana, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (A.B.) 2 Department of Biotechnology, Jožef Stefan Institute, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia * Correspondence: borut.strukelj@ffa.uni-lj.si Received: 16 September 2020; Accepted: 31 October 2020; Published: 1 November 2020 Abstract: The two most important bacterial phyla in the gastrointestinal tract, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, have gained much attention in recent years. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio is widely accepted to have an important influence in maintaining normal intestinal homeostasis. Increased or decreased F/B ratio is regarded as dysbiosis, whereby the former is usually observed with obesity, and the latter with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Probiotics as live microorganisms can confer health benefits to the host when administered in adequate amounts. There is considerable evidence of their nutritional and immunosuppressive properties including reports that elucidate the association of probiotics with the F/B ratio, obesity, and IBD. Orally administered probiotics can contribute to the restoration of dysbiotic microbiota and to the prevention of obesity or IBD. However, as the effects of different probiotics on the F/B ratio differ, selecting the appropriate species or mixture is crucial. The most commonly tested probiotics for modifying the F/B ratio and treating obesity and IBD are from the genus Lactobacillus. In this paper, we review the effects of probiotics on the F/B ratio that lead to weight loss or immunosuppression. -

Genomics 98 (2011) 370–375

Genomics 98 (2011) 370–375 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Genomics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ygeno Whole-genome comparison clarifies close phylogenetic relationships between the phyla Dictyoglomi and Thermotogae Hiromi Nishida a,⁎, Teruhiko Beppu b, Kenji Ueda b a Agricultural Bioinformatics Research Unit, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Tokyo, 1-1-1 Yayoi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8657, Japan b Life Science Research Center, College of Bioresource Sciences, Nihon University, Fujisawa, Japan article info abstract Article history: The anaerobic thermophilic bacterial genus Dictyoglomus is characterized by the ability to produce useful Received 2 June 2011 enzymes such as amylase, mannanase, and xylanase. Despite the significance, the phylogenetic position of Accepted 1 August 2011 Dictyoglomus has not yet been clarified, since it exhibits ambiguous phylogenetic positions in a single gene Available online 7 August 2011 sequence comparison-based analysis. The number of substitutions at the diverging point of Dictyoglomus is insufficient to show the relationships in a single gene comparison-based analysis. Hence, we studied its Keywords: evolutionary trait based on whole-genome comparison. Both gene content and orthologous protein sequence Whole-genome comparison Dictyoglomus comparisons indicated that Dictyoglomus is most closely related to the phylum Thermotogae and it forms a Bacterial systematics monophyletic group with Coprothermobacter proteolyticus (a constituent of the phylum Firmicutes) and Coprothermobacter proteolyticus Thermotogae. Our findings indicate that C. proteolyticus does not belong to the phylum Firmicutes and that the Thermotogae phylum Dictyoglomi is not closely related to either the phylum Firmicutes or Synergistetes but to the phylum Thermotogae. © 2011 Elsevier Inc. -

Detection of a Bacterial Group Within the Phylum Chloroflexi And

Microbes Environ. Vol. 21, No. 3, 154–162, 2006 http://wwwsoc.nii.ac.jp/jsme2/ Detection of a Bacterial Group within the Phylum Chloroflexi and Reductive-Dehalogenase-Homologous Genes in Pentachlorobenzene- Dechlorinating Estuarine Sediment from the Arakawa River, Japan KYOSUKE SANTOH1, ATSUSHI KOUZUMA1, RYOKO ISHIZEKI2, KENICHI IWATA1, MINORU SHIMURA3, TOSHIO HAYAKAWA3, TOSHIHIRO HOAKI4, HIDEAKI NOJIRI1, TOSHIO OMORI2, HISAKAZU YAMANE1 and HIROSHI HABE1*† 1 Biotechnology Research Center, The University of Tokyo, 1–1–1 Yayoi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113–8657, Japan 2 Department of Industrial Chemistry, Faculty of Engineering, Shibaura Institute of Technology, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108–8548, Japan 3 Environmental Biotechnology Laboratory, Railway Technical Research Institute, 2–8–38 Hikari-cho, Kokubunji-shi, Tokyo 185–8540, Japan 4 Technology Research Center, Taisei Corporation, 344–1 Nase, Totsuka-ku, Yokohama 245–0051, Japan (Received April 21, 2006—Accepted June 12, 2006) We enriched a pentachlorobenzene (pentaCB)-dechlorinating microbial consortium from an estuarine-sedi- ment sample obtained from the mouth of the Arakawa River. The sediment was incubated together with a mix- ture of four electron donors and pentaCB, and after five months of incubation, the microbial community structure was analyzed. Both DGGE and clone library analyses showed that the most expansive phylogenetic group within the consortium was affiliated with the phylum Chloroflexi, which includes Dehalococcoides-like bacteria. PCR using a degenerate primer set targeting conserved regions in reductive-dehalogenase-homologous (rdh) genes from Dehalococcoides species revealed that DNA fragments (approximately 1.5–1.7 kb) of rdh genes were am- plified from genomic DNA of the consortium. The deduced amino acid sequences of the rdh genes shared sever- al characteristics of reductive dehalogenases. -

Expanding the Chlamydiae Tree

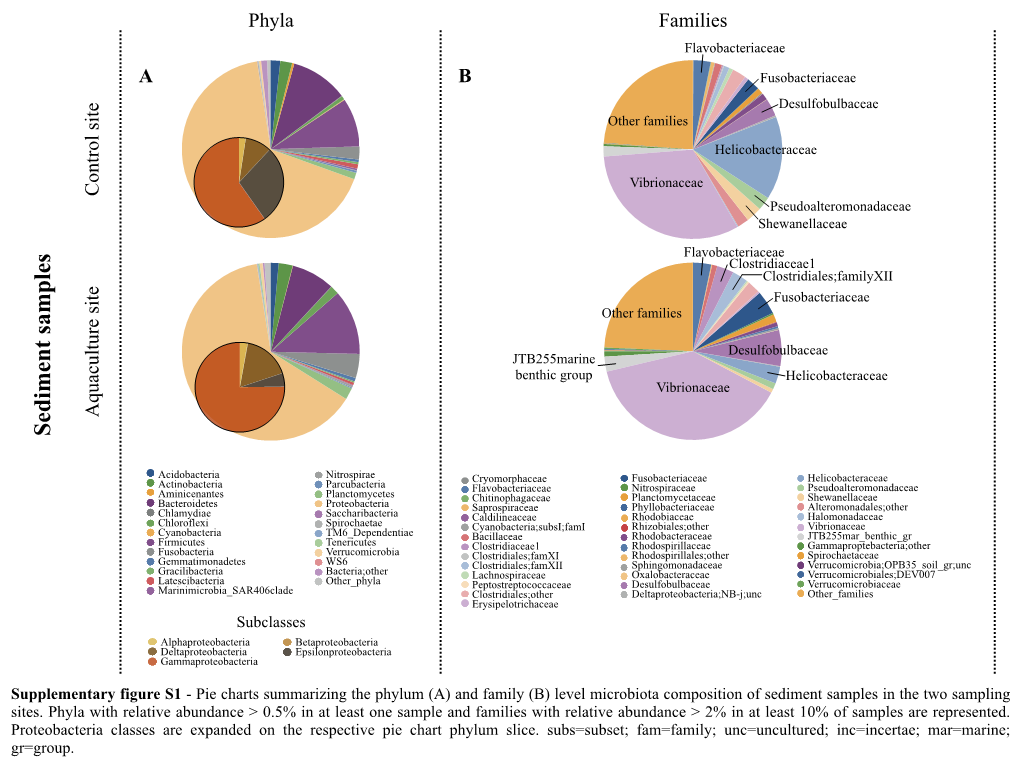

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 2040 Expanding the Chlamydiae tree Insights into genome diversity and evolution JENNAH E. DHARAMSHI ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6214 ISBN 978-91-513-1203-3 UPPSALA urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-439996 2021 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in A1:111a, Biomedical Centre (BMC), Husargatan 3, Uppsala, Tuesday, 8 June 2021 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Prof. Dr. Alexander Probst (Faculty of Chemistry, University of Duisburg-Essen). Abstract Dharamshi, J. E. 2021. Expanding the Chlamydiae tree. Insights into genome diversity and evolution. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 2040. 87 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-1203-3. Chlamydiae is a phylum of obligate intracellular bacteria. They have a conserved lifecycle and infect eukaryotic hosts, ranging from animals to amoeba. Chlamydiae includes pathogens, and is well-studied from a medical perspective. However, the vast majority of chlamydiae diversity exists in environmental samples as part of the uncultivated microbial majority. Exploration of microbial diversity in anoxic deep marine sediments revealed diverse chlamydiae with high relative abundances. Using genome-resolved metagenomics various marine sediment chlamydiae genomes were obtained, which significantly expanded genomic sampling of Chlamydiae diversity. These genomes formed several new clades in phylogenomic analyses, and included Chlamydiaceae relatives. Despite endosymbiosis-associated genomic features, hosts were not identified, suggesting chlamydiae with alternate lifestyles. Genomic investigation of Anoxychlamydiales, newly described here, uncovered genes for hydrogen metabolism and anaerobiosis, suggesting they engage in syntrophic interactions. -

(Batch Learning Self-Organizing Maps), to the Microbiome Analysis of Ticks

Title A novel approach, based on BLSOMs (Batch Learning Self-Organizing Maps), to the microbiome analysis of ticks Nakao, Ryo; Abe, Takashi; Nijhof, Ard M; Yamamoto, Seigo; Jongejan, Frans; Ikemura, Toshimichi; Sugimoto, Author(s) Chihiro The ISME Journal, 7(5), 1003-1015 Citation https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2012.171 Issue Date 2013-03 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/53167 Type article (author version) File Information ISME_Nakao.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP A novel approach, based on BLSOMs (Batch Learning Self-Organizing Maps), to the microbiome analysis of ticks Ryo Nakao1,a, Takashi Abe2,3,a, Ard M. Nijhof4, Seigo Yamamoto5, Frans Jongejan6,7, Toshimichi Ikemura2, Chihiro Sugimoto1 1Division of Collaboration and Education, Research Center for Zoonosis Control, Hokkaido University, Kita-20, Nishi-10, Kita-ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido 001-0020, Japan 2Nagahama Institute of Bio-Science and Technology, Nagahama, Shiga 526-0829, Japan 3Graduate School of Science & Technology, Niigata University, 8050, Igarashi 2-no-cho, Nishi- ku, Niigata 950-2181, Japan 4Institute for Parasitology and Tropical Veterinary Medicine, Freie Universität Berlin, Königsweg 67, 14163 Berlin, Germany 5Miyazaki Prefectural Institute for Public Health and Environment, 2-3-2 Gakuen Kibanadai Nishi, Miyazaki 889-2155, Japan 6Utrecht Centre for Tick-borne Diseases (UCTD), Department of Infectious Diseases and Immunology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Yalelaan 1, 3584 CL Utrecht, The Netherlands 7Department of Veterinary Tropical Diseases, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X04, 0110 Onderstepoort, South Africa aThese authors contributed equally to this work. Keywords: BLSOMs/emerging diseases/metagenomics/microbiomes/symbionts/ticks Running title: Tick microbiomes revealed by BLSOMs Subject category: Microbe-microbe and microbe-host interactions Abstract Ticks transmit a variety of viral, bacterial and protozoal pathogens, which are often zoonotic. -

Table S1. Bacterial Otus from 16S Rrna

Table S1. Bacterial OTUs from 16S rRNA sequencing analysis including only taxa which were identified to genus level (those OTUs identified as Ambiguous taxa, uncultured bacteria or without genus-level identifications were omitted). OTUs with only a single representative across all samples were also omitted. Taxa are listed from most to least abundant. Pitcher Plant Sample Class Order Family Genus CB1p1 CB1p2 CB1p3 CB1p4 CB5p234 Sp3p2 Sp3p4 Sp3p5 Sp5p23 Sp9p234 sum Gammaproteobacteria Legionellales Coxiellaceae Rickettsiella 1 2 0 1 2 3 60194 497 1038 2 61740 Alphaproteobacteria Rhodospirillales Rhodospirillaceae Azospirillum 686 527 10513 485 11 3 2 7 16494 8201 36929 Sphingobacteriia Sphingobacteriales Sphingobacteriaceae Pedobacter 455 302 873 103 16 19242 279 55 760 1077 23162 Betaproteobacteria Burkholderiales Oxalobacteraceae Duganella 9060 5734 2660 40 1357 280 117 29 129 35 19441 Gammaproteobacteria Pseudomonadales Pseudomonadaceae Pseudomonas 3336 1991 3475 1309 2819 233 1335 1666 3046 218 19428 Betaproteobacteria Burkholderiales Burkholderiaceae Paraburkholderia 0 1 0 1 16051 98 41 140 23 17 16372 Sphingobacteriia Sphingobacteriales Sphingobacteriaceae Mucilaginibacter 77 39 3123 20 2006 324 982 5764 408 21 12764 Gammaproteobacteria Pseudomonadales Moraxellaceae Alkanindiges 9 10 14 7 9632 6 79 518 1183 65 11523 Betaproteobacteria Neisseriales Neisseriaceae Aquitalea 0 0 0 0 1 1577 5715 1471 2141 177 11082 Flavobacteriia Flavobacteriales Flavobacteriaceae Flavobacterium 324 219 8432 533 24 123 7 15 111 324 10112 Alphaproteobacteria -

Cone-Forming Chloroflexi Mats As Analogs of Conical

268 Appendix 2 CONE-FORMING CHLOROFLEXI MATS AS ANALOGS OF CONICAL STROMATOLITE FORMATION WITHOUT CYANOBACTERIA Lewis M. Ward, Woodward W. Fischer, Katsumi Matsuura, and Shawn E. McGlynn. In preparation. Abstract Modern microbial mats provide useful process analogs for understanding the mechanics behind the production of ancient stromatolites. However, studies to date have focused on mats composed predominantly of oxygenic Cyanobacteria (Oxyphotobacteria) and algae, which makes it difficult to assess a unique role of oxygenic photosynthesis in stromatolite morphogenesis, versus different mechanics such as phototaxis and filamentous growth. Here, we characterize Chloroflexi-rich hot spring microbial mats from Nakabusa Onsen, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. This spring supports cone-forming microbial mats in both upstream high-temperature, sulfidic regions dominated by filamentous anoxygenic phototrophic Chloroflexi, as well as downstream Cyanobacteria-dominated mats. These mats produce similar morphologies analogous to conical stromatolites despite metabolically and taxonomically divergent microbial communities as revealed by 16S and shotgun metagenomic sequencing and microscopy. These data illustrate that anoxygenic filamentous microorganisms appear to be capable of producing similar mat morphologies as those seen in Oxyphotobacteria-dominated systems and commonly associated with 269 conical Precambrian stromatolites, and that the processes leading to the development of these features is more closely related with characteristics such as hydrology and cell morphology and motility. Introduction Stromatolites are “attached, lithified sedimentary growth structures, accretionary away from a point or limited surface of initiation” (Grotzinger and Knoll 1999). Behind this description lies a wealth of sedimentary structures with a record dating back over 3.7 billion years that may be one of the earliest indicators of life on Earth (Awramik 1992, Nutman et al. -

Downloaded 13 April 2017); Using Diamond

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/347021; this version posted June 14, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 2 3 4 5 Re-evaluating the salty divide: phylogenetic specificity of 6 transitions between marine and freshwater systems 7 8 9 10 Sara F. Pavera, Daniel J. Muratorea, Ryan J. Newtonb, Maureen L. Colemana# 11 a 12 Department of the Geophysical Sciences, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA 13 b School of Freshwater Sciences, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA 14 15 Running title: Marine-freshwater phylogenetic specificity 16 17 #Address correspondence to Maureen Coleman, [email protected] 18 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/347021; this version posted June 14, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 19 Abstract 20 Marine and freshwater microbial communities are phylogenetically distinct and transitions 21 between habitat types are thought to be infrequent. We compared the phylogenetic diversity of 22 marine and freshwater microorganisms and identified specific lineages exhibiting notably high or 23 low similarity between marine and freshwater ecosystems using a meta-analysis of 16S rRNA 24 gene tag-sequencing datasets. As expected, marine and freshwater microbial communities 25 differed in the relative abundance of major phyla and contained habitat-specific lineages; at the 26 same time, however, many shared taxa were observed in both environments. 27 Betaproteobacteria and Alphaproteobacteria sequences had the highest similarity between 28 marine and freshwater sample pairs. -

Table S4. Phylogenetic Distribution of Bacterial and Archaea Genomes in Groups A, B, C, D, and X

Table S4. Phylogenetic distribution of bacterial and archaea genomes in groups A, B, C, D, and X. Group A a: Total number of genomes in the taxon b: Number of group A genomes in the taxon c: Percentage of group A genomes in the taxon a b c cellular organisms 5007 2974 59.4 |__ Bacteria 4769 2935 61.5 | |__ Proteobacteria 1854 1570 84.7 | | |__ Gammaproteobacteria 711 631 88.7 | | | |__ Enterobacterales 112 97 86.6 | | | | |__ Enterobacteriaceae 41 32 78.0 | | | | | |__ unclassified Enterobacteriaceae 13 7 53.8 | | | | |__ Erwiniaceae 30 28 93.3 | | | | | |__ Erwinia 10 10 100.0 | | | | | |__ Buchnera 8 8 100.0 | | | | | | |__ Buchnera aphidicola 8 8 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pantoea 8 8 100.0 | | | | |__ Yersiniaceae 14 14 100.0 | | | | | |__ Serratia 8 8 100.0 | | | | |__ Morganellaceae 13 10 76.9 | | | | |__ Pectobacteriaceae 8 8 100.0 | | | |__ Alteromonadales 94 94 100.0 | | | | |__ Alteromonadaceae 34 34 100.0 | | | | | |__ Marinobacter 12 12 100.0 | | | | |__ Shewanellaceae 17 17 100.0 | | | | | |__ Shewanella 17 17 100.0 | | | | |__ Pseudoalteromonadaceae 16 16 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pseudoalteromonas 15 15 100.0 | | | | |__ Idiomarinaceae 9 9 100.0 | | | | | |__ Idiomarina 9 9 100.0 | | | | |__ Colwelliaceae 6 6 100.0 | | | |__ Pseudomonadales 81 81 100.0 | | | | |__ Moraxellaceae 41 41 100.0 | | | | | |__ Acinetobacter 25 25 100.0 | | | | | |__ Psychrobacter 8 8 100.0 | | | | | |__ Moraxella 6 6 100.0 | | | | |__ Pseudomonadaceae 40 40 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pseudomonas 38 38 100.0 | | | |__ Oceanospirillales 73 72 98.6 | | | | |__ Oceanospirillaceae -

Impact of Helicobacter Pylori Eradication Therapy on Gastric Microbiome

Impact of Helicobacter Pylori Eradication Therapy on Gastric Microbiome Liqi Mao The First Aliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5972- 4746 Yanlin Zhou The First Aliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University Shuangshuang Wang The First Aliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University Lin Chen The First Aliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University Yue Hu The First Aliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University Leimin Yu The First Aliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University Jingming Xu The First Aliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University Bin Lyu ( [email protected] ) First Aliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6247-571X Research Keywords: 16S rRNA gene sequencing, Helicobacter pylori, Eradication therapy, Gastric microora, Atrophic gastritis Posted Date: April 29th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-455395/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License 1 Impact of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on gastric microbiome 2 Liqi Mao 1,#, Yanlin Zhou 1,#, Shuangshuang Wang1,2, Lin Chen1, Yue Hu 1, Leimin Yu1,3, 3 Jingming Xu1, Bin Lyu1,* 4 1Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical 5 University, Hangzhou, China 6 2Department of Gastroenterology, Taizhou Hospital of Zhejiang Province affiliated to 7 Wenzhou Medical University, Taizhou, China 8 3Department of Gastroenterology, Guangxing Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang Chinese 9 Medical University, Hangzhou, China 10 #Liqi Mao and Yanlin Zhou contributed equally. 11 *Bin Lyu is the corresponding author, Email: [email protected]. -

Yu-Chen Ling and John W. Moreau

Microbial Distribution and Activity in a Coastal Acid Sulfate Soil System Introduction: Bioremediation in Yu-Chen Ling and John W. Moreau coastal acid sulfate soil systems Method A Coastal acid sulfate soil (CASS) systems were School of Earth Sciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia formed when people drained the coastal area Microbial distribution controlled by environmental parameters Microbial activity showed two patterns exposing the soil to the air. Drainage makes iron Microbial structures can be grouped into three zones based on the highest similarity between samples (Fig. 4). Abundant populations, such as Deltaproteobacteria, kept constant activity across tidal cycling, whereas rare sulfides oxidize and release acidity to the These three zones were consistent with their geological background (Fig. 5). Zone 1: Organic horizon, had the populations changed activity response to environmental variations. Activity = cDNA/DNA environment, low pH pore water further dissolved lowest pH value. Zone 2: surface tidal zone, was influenced the most by tidal activity. Zone 3: Sulfuric zone, Abundant populations: the heavy metals. The acidity and toxic metals then Method A Deltaproteobacteria Deltaproteobacteria this area got neutralized the most. contaminate coastal and nearby ecosystems and Method B 1.5 cause environmental problems, such as fish kills, 1.5 decreased rice yields, release of greenhouse gases, Chloroflexi and construction damage. In Australia, there is Gammaproteobacteria Gammaproteobacteria about a $10 billion “legacy” from acid sulfate soils, Chloroflexi even though Australia is only occupied by around 1.0 1.0 Cyanobacteria,@ Acidobacteria Acidobacteria Alphaproteobacteria 18% of the global acid sulfate soils. Chloroplast Zetaproteobacteria Rare populations: Alphaproteobacteria Method A log(RNA(%)+1) Zetaproteobacteria log(RNA(%)+1) Method C Method B 0.5 0.5 Cyanobacteria,@ Bacteroidetes Chloroplast Firmicutes Firmicutes Bacteroidetes Planctomycetes Planctomycetes Ac8nobacteria Fig. -

Supplementary Information For

1 2 Supplementary Information for 3 Quantifying the impact of treatment history on plasmid-mediated resistance evolution in 4 human gut microbiota 5 Burcu Tepekule, Pia Abel zur Wiesch, Roger Kouyos, Sebastian Bonhoeffer 6 Burcu Tepekule. 7 E-mail: [email protected] 8 This PDF file includes: 9 Figs. S1 to S6 10 Tables S1 to S2 11 References for SI reference citations Burcu Tepekule, Pia Abel zur Wiesch, Roger Kouyos, Sebastian Bonhoeffer 1 of 11 www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1912188116 12 Model parameters 13 The obtained growth rates are all positive, and consistent with the underlying biological assumptions, as well as the reported 14 growth rates in (1). Values obtained for interaction terms are all negative except one inter-phyla interaction term, which is 15 positive but small in magnitude. Hence, our numerical estimations for the interaction terms are dominated by competition, 16 which is shown to improve gut microbiome stability and permit high diversity of species to coexist (2). Statistics on the 17 parameter estimates are provided in Table S1 and Figures S1 and S2. Figure S1 shows that the phylum Firmicutes and 18 Actinobacteria do not affect the abundances of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes strongly due to their low inter-phyla interaction 19 rates. From the perspective of resistance evolution modeling, this indicates that the model can be reduced to two phyla 20 including Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes, since they are the only two phyla with the resistant variants. Dynamics of this 21 reduced model are presented in Figure S3, where three random treatment courses are applied on the 4-phyla (full) and 2-phyla 22 (reduced) models, and very similar results are observed.