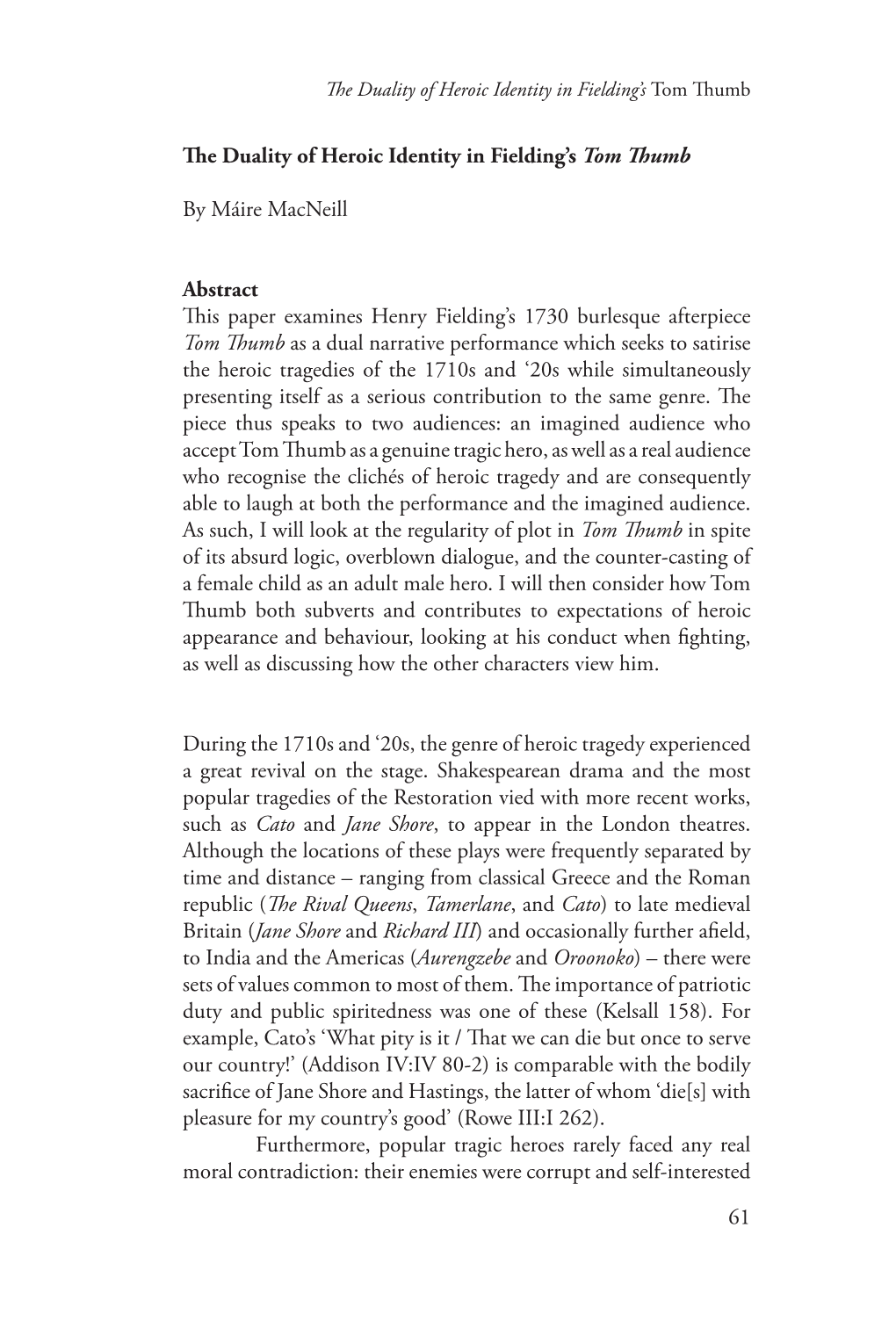

'The Duality of Heroic Identity in Fielding's Tom Thumb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOURCE01.Pdf

EPIC AND MOCK EPIC IN ENGLAND IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES J.S. RYAN Department of English University of New England Armidale , N S .14 1981 1981 Copyright is reserved to J.S. Ryan and Department of English, University of New England Printed by the University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales. CONTENTS Greek Epic 1 Epos 1 Aristotle 1 Epic setting 2 Simple action 2 Known story 3 Meaning of epic as critical term 4 Primitive epic 5 Primary epic Non Indo-European epic 6 Dantes L'ivine Comed 6 Secondary epic 7 Aeneid (--and Shaw) 7 Renaissance epic 8 Contemporary theme 9 Relation to the past 10 Style for secondary epic 11 Destiny and conscience 12 Responsibility 12 Classical influences - Milton 13 Satan 14 Like classical deities 15 Adams dilemma 16 Expulsion of Adam and Eve 18 Miltons focus 19 Walter Raleigh on Miltons Style 21 i iv Nimes and Nouns 71 John Dryden 22 Ancients Moderns 23 Nock heroic 24 Drydens mock heroics 24 pics in translation 26 Alexander Pope 26 Fielding and the epic novel 29 Samnel Richardsons Pamela 30 Fieldings classicism 31 The Town and Country 32 Social comedy and dignified picaresque 33 Including history 34 Sequel 34 The last epic poetry in english 35 BiblLography 37 GREEK EPIC Epic poetry, always associated in the mind of Western man the two homeric poems, the Iliad and the OdLissey, is both reckoned as the oldest and also ranked highest of the Greek literary types (being the first listed in Aristotles (2n the Art of Poetm, chap, 1). -

Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales Ballet Production Cast 2015

HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN’S FAIRY TALES BALLET PRODUCTION CAST 2015 (REVISED 12/4) The Storyteller (5:30 – 6:00pm Studio C) Hans Christian Andersen: TBD Storybook Children – Caroline Geiling, Alivia Sutter, Joleen Wobby, Madison White, Gianni Lombardi The Red Shoes (1:30– 2:00pm Studio D) Karen – Taylor Hollingsworth Shoemaker – Ellie Meck Red Shoe Dancers – Lillian Pisarczyk, Lily Buckner, Eden Stambaugh, Annalisa Conca, Annabelle Fait, Shalene Blanchard Ugly Duckling Baby Ducks (2:45‐3:15pm Studio D) ‐ Stella Pannacciulli, Reese Lockerman, Kaylee Wilson, Olivia Johnson, Addilynne Gaeta, Presley Moore, Paige Paulsen, Anya Contrino, Autumn O’Sullivan, Bria Patt Little Ugly Duckling (2:45‐3:15pm Studio D) – Maddy Blechschmidt Ducks (2:00‐2:30pm Studio B) – Sierra Anderson, Oliver Skiver, Sierra Blechschmidt, Sophia Kelly, McKinna Barnes, Kaitlynn Ellis, Natalie Beck, Eliza Engle, Samantha Fischer, Alex Morel, Sydney Madison, Madelyn Kamholz, Maya Wong, Mandie Simpson Swans (4:00‐4:30pm Studio B) – Megan Wagner, Maddie A’bell, Eliza Cervantes, Erin Klaerich, Valerie Yermian, Emma Marshall, Megan Overbey, Monique Dufault Grown Swan (4:00‐4:30pm Studio B) – Jillian Porath Mamma Duck (4:00‐4:30pm Studio B) – Narissa Urcioli Thumbelina Thumbelinas (3:30‐4:00pm Studio C) – Gabrielle Esposito, Nadia Gibbs, Sophia Parraga, Valeria Bedoya, Avery Paulsen, Reese Raymundo, Alyssia Garza, Lauren Shim, Zoe Dai Herrera, Grace Molina Tom Thumb (3:30‐4:00pm Studio C) – Will Weitz Lead Flowers (5:30‐6:00pm Studio D) – Charlotte Fait, Sidney Greene Flowers -

Knowledge 3 Teacher Guide Grade 1 Different Lands, Similar Stories Grade 1 Knowledge 3 Different Lands, Similar Stories

¬CKLA FLORIDA Knowledge 3 Teacher Guide Grade 1 Different Lands, Similar Stories Grade 1 Knowledge 3 Different Lands, Similar Stories Teacher Guide ISBN 978-1-68391-612-3 © 2015 The Core Knowledge Foundation and its licensors www.coreknowledge.org © 2021 Amplify Education, Inc. and its licensors www.amplify.com All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts and CKLA are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. References herein should not be regarded as affecting the validity of said trademarks and trade names. Printed in the USA 01 BR 2020 Grade 1 | Knowledge 3 Contents DIFFERENT LANDS, SIMILAR STORIES Introduction 1 Lesson 1 Cinderella 6 Introducing the Read-Aloud (10 min) Read-Aloud (30 min) Application (20 min) • Core Connections/Domain • Purpose for Listening • Vocabulary Instructional Activity: Introduction Instructions • “Cinderella” • Where Are We? • Somebody Wanted But So Then • Comprehension Questions • Word Work: Worthy Lesson 2 The Girl with the Red Slippers 22 Introducing the Read-Aloud (10 min) Read-Aloud (30 min) Application (20 min) • What Have We Already Learned? • Purpose for Listening • Drawing the Read-Aloud • Where Are We? • “The Girl with the Red Slippers” • Comprehension Questions • Word Work: Cautiously Lesson 3 Billy Beg 36 Introducing the Read-Aloud (10 min) Read-Aloud (30 min) Application (20 min) • What Have We Already Learned? • Purpose for Listening • -

Issun Boshi: One-Inch

IIssunssun BBoshi:oshi: OOne-Inchne-Inch BBoyoy 6 Lesson Objectives Core Content Objectives Students will: Explain that f ctional stories come from the author’s imagination Identify folktales as a type of f ction Explain that stories have a beginning, middle, and end Describe the characters, plot, and setting of “Issun Boshi: One- Inch Boy” Explain that people from different lands tell similar stories Language Arts Objectives The following language arts objectives are addressed in this lesson. Objectives aligning with the Common Core State Standards are noted with the corresponding standard in parentheses. Refer to the Alignment Chart for additional standards addressed in all lessons in this domain. Students will: Demonstrate understanding of the central message or lesson in “Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy” (RL.1.2) Recount and identify the lesson in folktales from diverse cultures, such as “Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy” (RL.1.2) Orally compare and contrast similar stories from different cultures, such as “Tom Thumb,” “Thumbelina,” and “Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy” (RL.1.9) Draw and describe one of the scenes from “Issun Boshi: One- Inch Boy” (W.1.2) Describe characters, settings, and events as depicted in drawings of one of the scenes from “Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy” (SL.1.4) Different Lands, Similar Stories 6 | Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy 79 © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation Add suff cient detail to a drawing of a scene from “Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy” (SL.1.5) Prior to listening to “Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy,” identify orally what they know and have learned about folktales, “Tom Thumb” and “Thumbelina” Core Vocabulary astonished, adj. -

Thesis-1969-P769l.Pdf

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE BURLESQUE ASPECTS OF JOSEPH.ANDREWS, A NOVEL BY HENRY FIELDING By ANNA COLLEEN POLK Bachelor of Arts Northeastern State College Tahlequah, Oklahoma 1964 Submitted to the Faculty ot the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1969 __ j OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 8iP 291969 THE IMPORTANCE OF THE BURLESQUE ASPECTS OF JOSEPH ANDREWS, A NOVEL BY HENRY FIELDING Thesis Approved: ~~ £~ 1{,· if'~ Jr-- Dean of the Graduate College 725038 ii PREFACE This thesis explores the·impottance of the burlesque aspects of Joseph Andrews, a novel by Henry Fielding· published in 1742. The· Preface. of.· the novel set forth a comic. theory which was entirely English and-which Fielding describes as a·11kind of writing, which l do not remember-· to have seen· hitherto attempted in our language". (xvii) •1 . The purpose of this paper will be to d.iscuss. the influence o:f; the burlesque .in formulating the new-genre which Fielding implies is the cow,:l..c equivalent of the epic. Now, .·a· comic· romance is a comic epic poem in prose 4iffering from comedy, as the--·serious epic from tragedy its action· being· more extended ·and· c'omp:rehensive; con tainiµg ·a ·much larger circle of·incidents, and intro ducing a greater ·variety of characters~ - lt differs :f;rO'J;l;l the serious romance in its fable and action,. in· this; that as in the one·these are·grave and solemn, ~o iil the other they·are·light:and:ridiculous: it• differs in its characters by introducing persons of. -

The Exceptionalism of General Tom Thumb, the Celebrity Body, and the American Dream

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2017 Self-Made Freak: The Exceptionalism of General Tom Thumb, The Celebrity Body, and the American Dream Megan Sonner College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Material Culture Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Cultural History Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Sonner, Megan, "Self-Made Freak: The Exceptionalism of General Tom Thumb, The Celebrity Body, and the American Dream" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1121. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1121 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Self-Made Freak: The Exceptionalism of General Tom Thumb, The Celebrity Body, and The American Dream A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies from The College of William & Mary by Megan Sonner Accepted for __________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _______________________________________ Kara Thompson, Director _______________________________________ Charles McGovern _______________________________________ -

THE TRAGEDY of TRAGEDIES OR the LIFE and DEATH of Tom Thumb the Great

THE TRAGEDY OF TRAGEDIES OR THE LIFE and DEATH OF Tom Thumb the Great Henry Fielding THE TRAGEDY OF TRAGEDIES OR THE LIFE and DEATH OF Tom Thumb the Great Table of Contents THE TRAGEDY OF TRAGEDIES OR THE LIFE and DEATH OF Tom Thumb the Great........................1 Henry Fielding...............................................................................................................................................2 ACT I.............................................................................................................................................................4 SCENE I.........................................................................................................................................................5 SCENE II.......................................................................................................................................................7 SCENE III......................................................................................................................................................8 SCENE IV....................................................................................................................................................11 SCENE V.....................................................................................................................................................12 SCENE VI....................................................................................................................................................14 ACT II..........................................................................................................................................................15 -

Errors and Reconciliations: Marriage in the Plays and Early Novels of Henry Fielding

ERRORS AND RECONCILIATIONS: MARRIAGE IN THE PLAYS AND EARLY NOVELS OF HENRY FIELDING ANACLARA CASTRO SANTANA SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT This thesis explores Henry Fielding’s fascination with marriage, and the importance of the marriage plot in his plays and early novels. Its main argument is twofold: it contends that Fielding presents marriage as symptomatic of moral and social evils on the one hand, and as a powerful source of moral improvement on the other. It also argues that the author imported and adapted the theatrical marriage plot—a key diegetic structure of stage comedies of the early eighteenth century—into his prose fictions. Following the hypothesis that this was his favourite narrative vehicle, as it proffered harmony between form and content, the thesis illustrates the ways in which Fielding transposed some of the well-established dramatic conventions of the marriage plot into the novel, a genre that was gaining in cultural status at the time. The Introduction provides background information for the study of marriage in Fielding’s work, offering a brief historical contextualization of marital laws and practices before the Marriage Act of 1753. Section One presents close readings of ten representative plays, investigating the writer’s first discovery of the theatrical marriage plot, and the ways in which he appropriated and experimented with it. The four chapters that compose the second part of the thesis trace the interrelated development of the marriage plot and theatrical motifs in Fielding’s early novels, namely Shamela (1741), Joseph Andrews (1742), Jonathan Wild (1743), and The Female Husband (1746). -

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 114 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address & security code. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #397 - W. Heath Robinson original artwork from Old Time Stories #175 - Lily Hildebrandt inscribed Klein-Raniers Weltreise #312 - First ed. in DW #65 - First issue in DW inscribed #111 - First Mickey Mouse book #236 - First issue Pat the Bunny in original box #228 - First ed. in dw #73 - Fine set first Appleton Alice 1866 & Macmillan Looking Glass #232 - Jessie King & Oscar Wilde #438 - JW Smith & E.S. Green Pg 3 Helen & Marc Younger [email protected] CLARA TICE DOG ALPHABET RABAN’S STUNNING HEBREW ABC 1. -

Favourite Fairy Tale: Tom Thumb Teaching Resources

TM Storytime Favourite Fairy Tale: Tom Thumb Teaching Resources Tom Thumb is an old English fairy tale about the amazing IN BRIEF adventures of a little boy who is only as tall as a thumb. 1 LITERACY LESSON IDEAS Read Tom Thumb, and have a class discussion. Use the following questions as a starting point: 1. Why were the ploughman and his wife unhappy? 2. What do you think life is like for someone as small as Tom? 3. What’s the best thing about being the size of a thumb? 4. What can Tom Thumb do that you can’t? Write a list. 5. What’s the worst thing about it? 6. What does the world look like from Tom’s perspective? (Think about how ordinary things like tall grass or a step could be a big obstacle) 7. Why do you think the beggar dropped the bowl of cake mixture? 8. Why does Tom’s mother worry about keeping him safe? 9. How many times does Tom escape from a tricky situation? 10. Why do you think King Arthur admired Tom so much? See our Tom Thumb Word Wise Sheet to discover the meanings of some of the less familiar words in the story and for more literacy activities. Arrange the story in the correct order on our Tom Thumb Story Sequencing Sheet. Tell the story in six paragraphs using our Tom Thumb Simple Storyboard. Which animals were featured in our story? Test your memory on our Character Comprehension Sheet. If you could be Tom Thumb for a day, what would you do? Write it down on our If I Were Tom Thumb Sheet. -

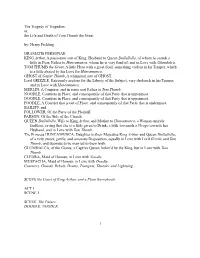

Or, the Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great By: Henry Fielding

The Tragedy of Tragedies; or, the Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great by: Henry Fielding DRAMATIS PERSONAE KING Arthur, A passionate sort of King, Husband to Queen Dollallolla, of whom he stands a little in Fear; Father to Huncamunca, whom he is very fond of; and in Love with Glumdalca. TOM THUMB the Great, A little Hero with a great Soul, something violent in his Temper, which is a little abated by his Love for Huncamunca. GHOST of Gaffar Thumb, A whimsical sort of GHOST. Lord GRIZZLE, Extremely zealous for the Liberty of the Subject, very cholerick in his Temper, and in Love with Huncamunca. MERLIN, A Conjurer, and in some sort Father to Tom Thumb. NOODLE, Courtiers in Place, and consequently of that Party that is uppermost. DOODLE, Courtiers in Place, and consequently of that Party that is uppermost. FOODLE, A Courtier that is out of Place, and consequently of that Party that is undermost. BAILIFF, and FOLLOWER, Of the Party of the Plaintiff. PARSON, Of the Side of the Church. QUEEN Dollallolla, Wife to King Arthur, and Mother to Huncamunca, a Woman entirely faultless, saving that she is a little given to Drink; a little too much a Virago towards her Husband, and in Love with Tom Thumb. The Princess HUNCAMUNCA, Daughter to their Majesties King Arthur and Queen Dollallolla, of a very sweet, gentle, and amorous Disposition, equally in Love with Lord Grizzle and Tom Thumb, and desirous to be married to them both. GLUMDALCA, of the Giants, a Captive Queen, belov'd by the King, but in Love with Tom Thumb. -

Una-Theses-0312.Pdf

HEN R Y FIE L DIN G THE 0 R Y o F THE COM I C A thesis submitted to the faculty of the GRADUATE SChOOL of the UNIV~RSITY of - INN~SOTA by DAGMAR DONEGHY • In partial fulfillment of the requirements for ~he degree of Master of Arts . June 1916. RltPORT of Committee on Thesis The undersigned, acting as a Committee of the Graduate School, have r ead the accompanying thesis submttted by SD.~ ..~ . .!! . .~.~ .... ~ for the degree of .~. .~ .. ...... ~.. ..~ ...................... ............ They approve it as a thesis meeting tho require- menta of the Grad ate School of t h e Un iv@raity of :Minnesota, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the r e quirements for the degree of .~~ ...a. .. ~....... ..... ......... ....- .. .............. -.................... .-:.::d.@. _.. -.. -~........ ..... -....... -.... --~-.. ' _.... -_ ...... - ....- ..• _- ..... __ .-........_ ... _.. _.... .... _..... ........ __ ._ .. __ .............. __ ._ .. _.... _.......... _._ ...... _..... _.- BIB L lOG RAP H Y. Henry Fi elding : Love i n Several 4asgues. London, ~n ith ~ lder & co., 1882. Th e l' empl e Heau. London, Smith Elder & Co. 1882. The Justice Caught in his Own Trap. London, Smith Elder & Co., 1882. The ~odern Husband. London, ~mith Elder a co ., 1 882. ~~ he Debauch ees. London, Smith Elder & Co., 1882. Don Quixote in England . London, Smith Elder & Co., 1882. 'rhe Universal Gallan t. London, Smi th Elder ?r. Co., 1882. The 'I/ edci ing Day . London , :::;w i th .l!; l de r c~ Co., 1882. The Good-Natured Man . London. Smith Elder & Co., 1882. The Letter "lri ters or A New Way to Keep a 1/ife at Home , London, ~n ith ~ lder & co., 1882.