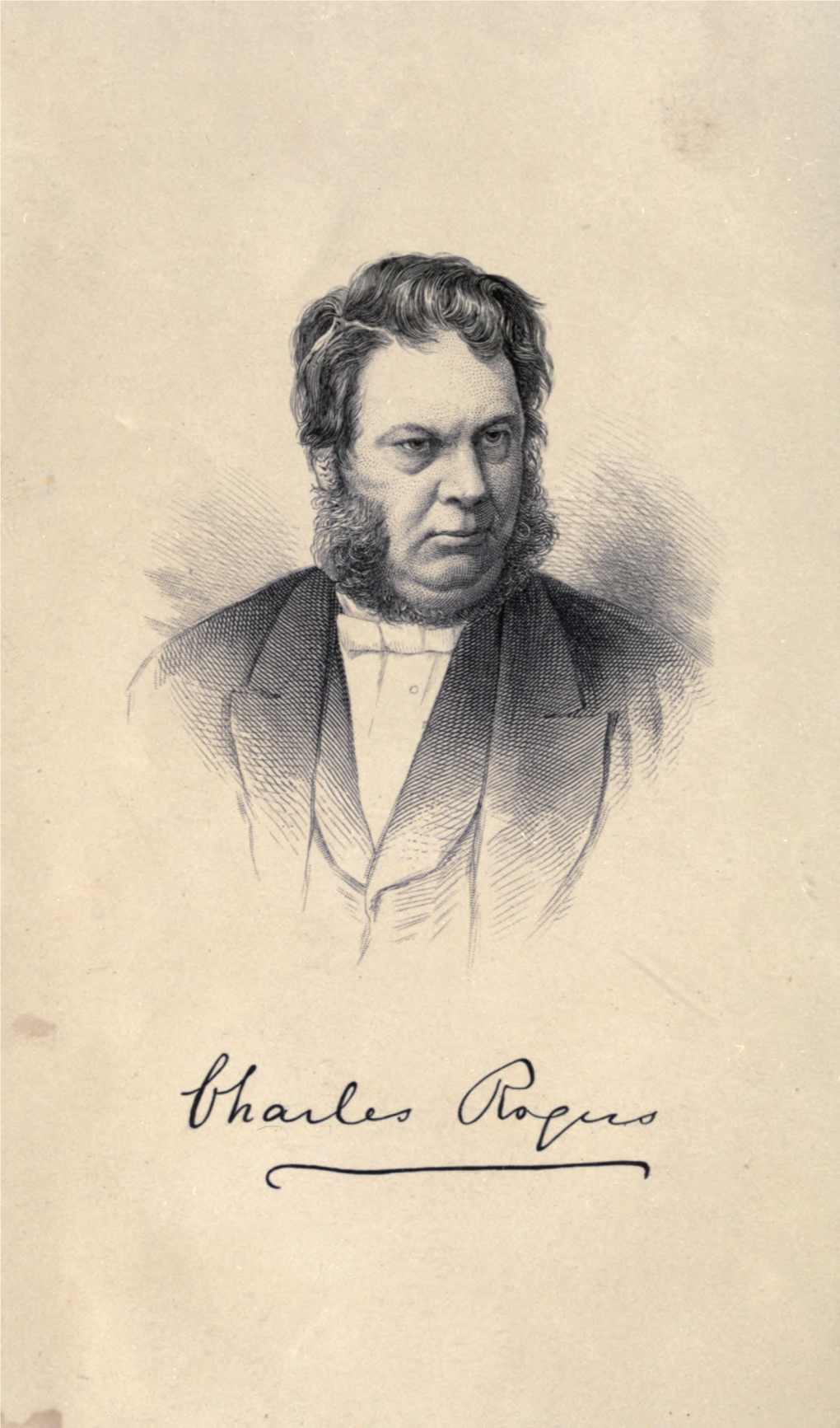

Scottish Life Memorials and Recollections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DENNISTOUN Stop 3 the LADY WELL LIBRARY the Park Opened in 1870 (Category B-Listed) the Lady Well Is on and Was Named After the Library Opened in 1905

Stop 1 ALEXANDRA PARK Stop 2 DENNISTOUN Stop 3 THE LADY WELL LIBRARY The park opened in 1870 (Category B-listed) The Lady Well is on and was named after The Library opened in 1905. It is called a Carnegie the site of an ancient Princess Alexandra. At the Library because it was built using money donated by well that provided entrance is the Andrew Carnegie, a man born in Scotland who water for the people of Cruikshank Fountain. moved to America and became one of the richest Glasgow before it was common to have Look closely at the people who ever lived. He donated money to build running water inside fountain, what kind of over 2000 libraries across the world. The your home. animal do you see on the Dennistoun Library has a special statue which is inside? called the “Dennistoun Angel”. Can you find it? DENNISTOUN Don’t forget to look up! KIDS’ TRAIL Can you draw the well here? Inside the park there is lots to see and do, including ponds, a playground and the beautiful Saracen Fountain which is over 12 metres tall! There are four different statues on the fountain, can you see what they’re holding? Stop 4 BUFFALO BILL Stop 5 WELLPARK BREWERY Stop 6 NECROPOLIS Stop 7 CATHEDRAL (Category A-listed) (Category A-listed) In 1891 Buffalo Bill, One of the most famous and well Wellpark Brewery was first known as the Drygate Glasgow Necropolis Glasgow Cathedral is one of the oldest buildings known figures of the American Old West, brought his Brewery, a brewery is a place where beer is made.It was the first garden in Glasgow and the only mediaeval cathedral in “Wild West Show” to the very spot where his statue is was founded in 1740 by Hugh and Robert Tennent but cemetery in Scotland. -

The Scottish Genealogist

THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGY SOCIETY THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGIST INDEX TO VOLUMES LIX-LXI 2012-2014 Published by The Scottish Genealogy Society The Index covers the years 2012-2014 Volumes LIX-LXI Compiled by D.R. Torrance 2015 The Scottish Genealogy Society – ISSN 0330 337X Contents Please click on the subject to be visited. ADDITIONS TO THE LIBRARY APPRECIATIONS ARTICLE TITLES BOOKMARKS BOOK REVIEWS CONTRIBUTORS FAMILY TREES GENERAL INDEX ILLUSTRATIONS INTRODUCTION QUERIES INTRODUCTION Where a personal or place name is mentioned several times in an article, only the first mention is indexed. LIX, LX, LXI = Volume number i. ii. iii. iv = Part number 1- = page number ; - separates part numbers within the same volume : - separates volume numbers BOOKMARKS The contents of this CD have been bookmarked. Select the second icon down at the left-hand side of the document. Use the + to expand a section and the – to reduce the selection. If this icon is not visible go to View > Show/Hide > Navigation Panes > Bookmarks. Recent Additions to the Library (compiled by Joan Keen & Eileen Elder) LIX.i.43; ii.102; iii.154: LX.i.48; ii.97; iii.144; iv.188: LXI.i.33; ii.77; iii.114; Appreciations 2012-2014 Ainslie, Fred LIX.i.46 Ferguson, Joan Primrose Scott LX.iv.173 Hampton, Nettie LIX.ii.67 Willsher, Betty LIX.iv.205 Article Titles 2012-2014 A Call to Clan Shaw LIX.iii.145; iv.188 A Case of Adultery in Roslin Parish, Midlothian LXI.iv.127 A Knight in Newhaven: Sir Alexander Morrison (1799-1866) LXI.i.3 A New online Medical Database (Royal College of Physicians) -

East Neuk Community Forum- Zoom Meeting-15/10/20, Chaired by Martin Dibbs, Kingsbarns Community Council

EAST NEUK COMMUNITY FORUM- ZOOM MEETING-15/10/20, CHAIRED BY MARTIN DIBBS, KINGSBARNS COMMUNITY COUNCIL PRESENT; VARIOUS COMMUNITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVES, INCLUDING CRAIL, ANSTRUTHER, KINGSBARNS, BOARHILLS AND DUNINO, ELIE AND PITTENWEEM COUNCILLORS HOLT, PORTEOUS AND DOCHERTY COUNCILLOR ROSS VETTRAINO, FIFE COUNCIL, CONVENER- ENVIRONMENT, PROTECTIVE SERVICES AND COMMUNITY SAFETY COMMITTEE GILLIAN DUNCAN, EAST NEUK FIRST RESPONDERS AND ENCEPT (EAST NEUK COMMUNITY EMERGENCY PLANNING TEAM) SONJA POTJEWIJD AND CRISPIN HAYES, ENCAP (EAST NEUK COMMUNITY ACTION PLAN) APOLOGIES; POLICE SCOTLAND 1. RECYCLING CENTRES IN EAST NEUK There have been various issues since March 2020, due to lockdown with people accessing recycling centres in our area. Particularly with people who do not access to a computer to be able to book times, the elderly in particular and Fife council’s refusal for pick ups, larger vehicles, vans and trailers to be allowed in to drop off rubbish. Councillor Holt stressed the difference between our area, being largely rural and agricultural compared to cities to Councillor Vettraino. She also stressed that we have one of the largest proportion of over 85’s in our area who have needs to be addressed regarding the above topic and especially need further help during covid. Councillor Vettraino advised that trailers, some pickups are now allowed to use the recycling centres. White goods can now be unloaded, as well wood. Rubble cannot be unloaded. AirBnb rubbish is counted as commercial so they should not be using facility. Question was asked whether the recycling centre at Pittenweem could change its opening times, Councillor Vettraino to check. 2. REWILDING Various comments were made by CC’s that there had been no consultation between fife council and the CC’s regarding rewilding in the east Neuk. -

“In Loving Memory”

April 2012 www.safhs.org.uk Executive Committee: Chairman: Bruce B Bishop; Deputy Chairman: vacant; Secretary: Ken Nisbet; Treasurer: John W Irvine; Editor: Janet M Bishop; Publications Manager: vacant ******************************************************************************************************************************************* *** SAFHS Conference 2012, Dundee The post of Deputy Chairman is vacant and will be advertised in the usual way before the AGM 2013. Hosted by Tay Valley FHS & Fife FHS rd The post of Publications Manager is vacant and will be he 23 SAFHS Annual Conference is being held in the advertised in the usual way before the AGM 2103. Bonar Halls, Dundee University, on Saturday 21 April T 2012. It is a joint venture this year between Tay Valley Website FHS and Fife FHS Would you please submit anything you have for the website to Doug any changes to your website contact should also be Please see the SAFHS website for details. – ___________________________________________________ sent direct to Doug. Contacts List SAFHS CONTACTS Please note that the official contacts list is kept and updated by Chairman the Editor, then circulated to the members of the Executive Bruce B Bishop: Committee and the webmaster. If there are any changes in Deputy Chairman office bearers, reps, email addresses, mailing addresses, phone Vacant numbers, etc, between Council Meeting updates, can you Secretary please send them direct to Janet Bishop. Ken Nisbet: Treasurer ScotlandsPeople Vouchers – Orders John W Irvine: All orders for ScotlandsPeople Vouchers should be sent to John Editor W Irvine, Treasurer, at 3 Grants Wynd, Bridgefoot, Angus, Janet M Bishop: DD3 0RZ. All orders must be accompanied by a cheque and Publications should include postage, as per the current agreement, which is vacant as follows. -

New SNH Firth of Tay/Eden

COMMISSIONED REPORT Commissioned Report No. 007 Broad scale mapping of habitats in the Firth of Tay and Eden Estuary, Scotland (ROAME No. F01AA401D) For further information on this report please contact: Dan Harries Maritime Group Scottish Natural Heritage 2 Anderson Place EDINBURGH EH6 5NP Telephone: 0131–446 2400 E-mail: [email protected] This report should be quoted as: Bates, C. R., Moore, C. G., Malthus, T., Mair, J. M. and Karpouzli, E. (2004). Broad scale mapping of habitats in the Firth of Tay and Eden Estuary, Scotland. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 007 (ROAME No. F01AA401D). This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of Scottish Natural Heritage. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. The views expressed by the author(s) of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Natural Heritage 2003. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 007 (ROAME No. F01AA401D) This report was produced for Scottish Natural Heritage by the Sedimentary Systems Research Unit, University of St Andrews, the School of Life Sciences Heriot-Watt University and the Department of Geography, University of Edinburgh on the understanding that the final data provided can be used only by these parties and SNH. Dr Richard Bates Sedimentary Systems Research Unit School of Geography and Geosciences University of St Andrews St Andrews Dr Colin Moore School of Life Sciences Heriot-Watt University Edinburgh Dr Tim Malthus Department of Geography University of Edinburgh Edinburgh SUPPORTING INFORMATION: Scottish Natural Heritage holds all other non-published data products arising from this mapping project including raw sediment PSA data, video footage, raw acoustic data and GIS products. -

The Edinburgh Gazette, November 17, 1953 603

THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 17, 1953 603 Factory Department, TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (SCOTLAND) Ministry of Labour and National Service, ACTS, 1947 AND 1951 8 St. James's Square, London, S.W.I, 4th November 1953. TOWN COUNCIL OF THE BURGH OF MOTHERWELL The Chief Inspector of Factories has appointed Dr. C. R. AND WISHAW Innes to be Appointed Factory Doctor under the Factories DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR THE BURGH Acts, 1937 and 1948, for the Barra District of the County of Inverness. NOTICE is hereby given that, on the 30th day of October 1953, the Secretary of State approved, with modifications, the above Development Plan. A certified copy of the Development Pjan, as approved by the Secretary of State, has been deposited at the office of the Subscriber in the Town Hall, Motherwell. SUPPLIES AND SERVICES The copy of the Development Plan, so deposited, is COAL PRICES available for inspection by the public, free of charge, between the hours of 9 o'clock a.m. and 5 o'clock p.m. on The Minister of Fuel and Power hereby gives notice that each weekday, and between the hours of 9 o'clock a.m. he has made the Coal Prices Orders (Bunkers and Whole- and 12 o'clock noon on Saturdays. sale) (Revocation) Order, 1953-^S.I. 1953, No. 1626, copies The Development Plan became operative as from the of which may be purchased direct from H.M. Stationery 13th day of November 1953, but if any person aggrieved Office at the following addresses:—York House, Kingsway, by the Development Plan desires to question the validity London, W.C.2; 13A Castle Street, Edinburgh, 2; 39 King thereof, or of any provision contained therein, on the Street, Manchester, 2; 2 Edmund Street, Birmingham, 3; ground that it is not within the powers of the Town and 1 St. -

Fife Burial Records

FIFE COUNCIL BEREAVEMENT SERVICES CEMETERIES (Including Disused Churchyards) WEST AREA: (Dunfermline Crematorium Lodge, Masterton Road, Dunfermline, KY11 8QR, Tel: 01383 602335, Fax: 01383 602665.) 1. Dunfermline Cemetery, Halbeath Road, Dunfermline 2. Aberdour Cemetery incl Churchyard, entrance off Mill Farm Road, Aberdour 3. Dalgety Churchyard, Four Lums Road, Dalgety Bay 4. Hillend Cemetery, Clockluine Road, Hillend 5. Inverkeithing (Hope Street Cemetery), off Hope Street, Inverkeithing 6. Douglas Bank Cemetery, Pattiesmuir, by Rosyth 7. Torryburn Cemetery, B9037 to Torryburn 8. Culross Cemetery, Blairhall Glen, Shire Road, Culross, off A985(T) 9. Tulliallan Cemetery, Toll Road, Kincardine 10. Saline Cemetery, Drumhead, North Road, Saline 11. Beath Cemetery incl Churchyard, Old Perth Road, Cowdenbeath 12. Lochgelly Cemetery, A910 (Jamphlars Road) to Cardenden 13. Ballingry Cemetery, Hill Road, Ballingry 14. St. Fillans Churchyard, Hawkcraig Road, Aberdour 15. Ballingry Old Churchyard, Hill Road, Ballingry 16. Carnock Cemetery, Main Street, Carnock 17. Cairneyhill Churchyard, behind Church, Main Street, Cairneyhill 18. Crombie Churchyard, Crombie Point 19. Culross Abbey Churchyard, Kirk Street, Culross 20. West Kirk Churchyard, by Upper Dean, Culross 21. Dunfermline Abbey, St Margaret Street, Dunfermline 22. Inverkeithing (St Peters) Churchyard, High Street, Inverkeithing 23. Mossgreen Cemetery, Coaledge, By Crossgates 24. North Queensferry Churchyard, Chapel Place, North Queensferry 25. Rosyth Old Churchyard, via Brucehaven Road and track from harbour, Limekilns 26. Saline Old Churchyard, Bridge Street, Saline 27. Torryburn Churchyard, Main Street, Torryburn 28. Woodlea Old Cemetery, Woodlea, Kincardine 29. St James Churchyard, North Queensferry 1 FIFE COUNCIL BEREAVEMENT SERVICES CEMETERIES (Including Disused Churchyards) CENTRAL AREA: Kirkcaldy: (Kirkcaldy Crematorium Lodge, Rosemount Avenue, Dunnikier, Kirkcaldy, KY1 3PL, Tel: 01592 583524, Fax: 01592 203438) 1. -

Creich Church 9.30Am 17 Maundy Thursday Kilmany Church 7.00Pm 18 Good Friday Kilmany Church 7.00Pm 20 Easter Sunday Kilmany Church 9.30Am

CFK PARISH NEWS F L CREICHI S & KILMANYK Spring 2014 Your District Elder is: www.cfk-monimail.org.uk AFTERNOON CLUB The Afternoon Club meet in Luthrie Hall on the first Monday of the month , 2pm till 3.30pm. For a fun afternoon, of games, sing- along songs and speakers together with a selection of lovely home baking- come along and see what it’s all about. Everyone welcome. Creich Flisk and Kilmany Church of Scotland Scottish Charity No. SC001097 Locum’s Letter Dear Friends I am enjoying getting to know the linked parish of Monimail, Flisk, Creich and Kilmany, a lovely part of Fife which, until now, I knew very little about. My contract is for one day a week in addition to the Sunday services and I hope to get to know you better and to be able to help where I can in an unsettling time. Like many parishes in Scotland today, you are involved in vacancy procedures at a time when numbers coming forward to serve the Church are at an all time low. I have been involved in ministry for 46 years, the first 20 years as parish minister in Dunfermline, followed by 2 years as Deputy Secretary in the Committee of Education for the Ministry, with specific responsibility for the recruitment and training of candidates. These were exciting times, with numbers training for ministry the highest they had been for years. In the late 1980s I was working with about 200 students in the four colleges, while today numbers are in the low 60s. -

I General Area of South Quee

Organisation Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line3 City / town County DUNDAS PARKS GOLFGENERAL CLUB- AREA IN CLUBHOUSE OF AT MAIN RECEPTION SOUTH QUEENSFERRYWest Lothian ON PAVILLION WALL,KING 100M EDWARD FROM PARK 3G PITCH LOCKERBIE Dumfriesshire ROBERTSON CONSTRUCTION-NINEWELLS DRIVE NINEWELLS HOSPITAL*** DUNDEE Angus CCL HOUSE- ON WALLBURNSIDE BETWEEN PLACE AG PETERS & MACKAY BROS GARAGE TROON Ayrshire ON BUS SHELTERBATTERY BESIDE THE ROAD ALBERT HOTEL NORTH QUEENSFERRYFife INVERKEITHIN ADJACENT TO #5959 PEEL PEEL ROAD ROAD . NORTH OF ENT TO TRAIN STATION THORNTONHALL GLASGOW AT MAIN RECEPTION1-3 STATION ROAD STRATHAVEN Lanarkshire INSIDE RED TELEPHONEPERTH ROADBOX GILMERTON CRIEFFPerthshire LADYBANK YOUTHBEECHES CLUB- ON OUTSIDE WALL LADYBANK CUPARFife ATR EQUIPMENTUNNAMED SOLUTIONS ROAD (TAMALA)- IN WORKSHOP OFFICE WHITECAIRNS ABERDEENAberdeenshire OUTSIDE DREGHORNDREGHORN LOAN HALL LOAN Edinburgh METAFLAKE LTD UNITSTATION 2- ON ROAD WALL AT ENTRANCE GATE ANSTRUTHER Fife Premier Store 2, New Road Kennoway Leven Fife REDGATES HOLIDAYKIRKOSWALD PARK- TO LHSROAD OF RECEPTION DOOR MAIDENS GIRVANAyrshire COUNCIL OFFICES-4 NEWTOWN ON EXT WALL STREET BETWEEN TWO ENTRANCE DOORS DUNS Berwickshire AT MAIN RECEPTIONQUEENS OF AYRSHIRE DRIVE ATHLETICS ARENA KILMARNOCK Ayrshire FIFE CONSTABULARY68 PIPELAND ST ANDREWS ROAD POLICE STATION- AT RECEPTION St Andrews Fife W J & W LANG LTD-1 SEEDHILL IN 1ST AID ROOM Paisley Renfrewshire MONTRAVE HALL-58 TO LEVEN RHS OFROAD BUILDING LUNDIN LINKS LEVENFife MIGDALE SMOLTDORNOCH LTD- ON WALL ROAD AT -

Codebook for IPUMS Great Britain 1851-1881 Linked Dataset

Codebook for IPUMS Great Britain 1851-1881 linked dataset 1 Contents SAMPLE: Sample identifier 12 SERIAL: Household index number 12 SEQ: Index to distinguish between copies of households with multiple primary links 12 PERNUM: Person index within household 13 LINKTYPE: Link type 13 LINKWT: Number of cases in linkable population represented by linked case 13 NAMELAST: Last name 13 NAMEFRST: First name 13 AGE: Age 14 AGEMONTH: Age in months 14 BPLCNTRY: Country of birth 14 BPLCTYGB: County of birth, Britain 20 CFU: CFU index number 22 CFUSIZE: Number of people in individuals CFU 23 CNTRY: Country of residence 23 CNTRYGB: Country within Great Britain 24 COUNTYGB: County, Britain 24 ELDCH: Age of eldest own child in household 27 FAMSIZE: Number of own family members in household 27 FAMUNIT: Family unit membership 28 FARM: Farm, NAPP definition 29 GQ: Group quarters 30 HEADLOC: Location of head in household 31 2 HHWT: Household weight 31 INACTVGB: Adjunct occupational code (Inactive), Britain 31 LABFORCE: Labor force participation 51 MARRYDAU: Number of married female off-spring in household 51 MARRYSON: Number of married male off-spring in household 51 MARST: Marital status 52 MIGRANT: Migration status 52 MOMLOC: Mothers location in household 52 NATIVITY: Nativity 53 NCHILD: Number of own children in household 53 NCHLT10: Number of own children under age 10 in household 53 NCHLT5: Number of own children under age 5 in household 54 NCOUPLES: Number of married couples in household 54 NFAMS: Number of families in household 54 NFATHERS: Number of fathers -

The Scottish Genealogist

THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGY SOCIETY THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGIST INDEX TO VOLUMES LIX-LXI 2012-2014 Published by The Scottish Genealogy Society The Index covers the years 2012-2014 Volumes LIX-LXI Compiled by D.R. Torrance 2015 The Scottish Genealogy Society – ISSN 0330 337X Contents Appreciations 1 Article Titles 1 Book Reviews 3 Contributors 4 Family Trees 5 General Index 9 Illustrations 6 Queries 5 Recent Additions to the Library 5 INTRODUCTION Where a personal or place name is mentioned several times in an article, only the first mention is indexed. LIX, LX, LXI = Volume number i. ii. iii. iv = Part number 1- = page number ; - separates part numbers within the same volume : - separates volume numbers Appreciations 2012-2014 Ainslie, Fred LIX.i.46 Ferguson, Joan Primrose Scott LX.iv.173 Hampton, Nettie LIX.ii.67 Willsher, Betty LIX.iv.205 Article Titles 2012-2014 A Call to Clan Shaw LIX.iii.145; iv.188 A Case of Adultery in Roslin Parish, Midlothian LXI.iv.127 A Knight in Newhaven: Sir Alexander Morrison (1799-1866) LXI.i.3 A New online Medical Database (Royal College of Physicians) LX.iv.177 A very short visit to Scotslot LIX.iii.144 Agnes de Graham, wife of John de Monfode, and Sir John Douglas LXI.iv.129 An Octogenarian Printer’s Recollections LX.iii.108 Ancestors at Bannockburn LXI.ii.39 Andrew Robertson of Gladsmuir LIX.iv.159: LX.i.31 Anglo-Scottish Family History Society LIX.i.36 Antiquarian is an odd name for a society LIX.i.27 Balfours of Balbirnie and Whittinghame LX.ii.84 Battle of Bannockburn Family History Project LXI.ii.47 Bothwells’ Coat-of-Arms at Glencorse Old Kirk LX.iv.156 Bridges of Bishopmill, Elgin LX.i.26 Cadder Pit Disaster LX.ii.69 Can you identify this wedding party? LIX.iii.148 Candlemakers of Edinburgh LIX.iii.139 Captain Ronald Cameron, a Dungallon in Morven & N. -

Special Offers Heraldry Trades & Professions History Vital Records – Births, Marriage, Deaths Irish Ancestry Wills & Testaments

SCOTTISH GENEALOGY SOCIETY SALES CATALOGUE OCTOBER 2013 PLEASE NOTE THAT THE FULL SALES CATALOGUE IS AVAILABLE ONLINE AT: WWW.SCOTSGENEALOGY.COM/DOWNLOADS.ASPX THE CATALOGUE IS IN SECTIONS AS FOLLOWS SECTION TITLE SECTION TITLE JACOBITES ARMED FORCES MARINERS & SHIPS BURGH RECORDS MISCELLANEOUS CASTLES OF SCOTLAND MONUMENTAL INSCRIPTIONS CENSUS NAMES DIRECTORIES PEERAGE ECCLESIASTICAL PEOPLE & POLL TAX LISTS OF 1696 EDUCATION POLL & HEARTH TAX EMIGRANTS & IMMIGRANTS SOURCES & GUIDES HEIRS – CD ROM SPECIAL OFFERS HERALDRY TRADES & PROFESSIONS HISTORY VITAL RECORDS – BIRTHS, MARRIAGE, DEATHS IRISH ANCESTRY WILLS & TESTAMENTS All the sections are bookmarked in the pdf catalogue. To calculate the cost of postage take a note of the weight of the goods and consult the postage table at the back of the sales catalogue. This is only a guideline and we reserve the right to increase prices when necessary. Please indicate whether airmail or surface for overseas members and whether first or second class for UK members. Payment may be made in sterling. The sterling equivalent may be obtained from your local bank. The Society accepts MASTER, VISA OR MAESTRO cards The Society reserves the right to alter prices in accordance with changes in publishing costs. PLEASE ENSURE THE CARDHOLDER'S NAME, CARD NUMBER, EXPIRY DATE AND TYPE OF CARD, I.E. VISA OR MASTER, ARE CLEARLY STATED. DISCOUNT Members of the Society are allowed a discount of 10% on Scottish Genealogy Society publications marked with an * (excluding postage and packing) Enquiries regarding trade discount should be directed to The Sales Secretary 15 Victoria Terrace, Edinburgh EH1 2JL Scotland Fax and Tel. No. (UK) 0131 220 3677 E-mail addresses Sales only [email protected] Renewal of membership only [email protected] Website and online shop www.scotsgenealogy.com Scottish Charity No.