A Pluto-Like Radius and a High Albedo for the Dwarf Planet Eris from an Occultation Bruno Sicardy, J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modeling Super-Earth Atmospheres in Preparation for Upcoming Extremely Large Telescopes

Modeling Super-Earth Atmospheres In Preparation for Upcoming Extremely Large Telescopes Maggie Thompson1 Jonathan Fortney1, Andy Skemer1, Tyler Robinson2, Theodora Karalidi1, Steph Sallum1 1University of California, Santa Cruz, CA; 2Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ ExoPAG 19 January 6, 2019 Seattle, Washington Image Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle Roadmap Research Goals & Current Atmosphere Modeling Selecting Super-Earths for State of Super-Earth Tool (Past & Present) Follow-Up Observations Detection Preliminary Assessment of Future Observatories for Conclusions & Upcoming Instruments’ Super-Earths Future Work Capabilities for Super-Earths M. Thompson — ExoPAG 19 01/06/19 Research Goals • Extend previous modeling tool to simulate super-Earth planet atmospheres around M, K and G stars • Apply modified code to explore the parameter space of actual and synthetic super-Earths to select most suitable set of confirmed exoplanets for follow-up observations with JWST and next-generation ground-based telescopes • Inform the design of advanced instruments such as the Planetary Systems Imager (PSI), a proposed second-generation instrument for TMT/GMT M. Thompson — ExoPAG 19 01/06/19 Current State of Super-Earth Detections (1) Neptune Mass Range of Interest Earth Data from NASA Exoplanet Archive M. Thompson — ExoPAG 19 01/06/19 Current State of Super-Earth Detections (2) A Approximate Habitable Zone Host Star Spectral Type F G K M Data from NASA Exoplanet Archive M. Thompson — ExoPAG 19 01/06/19 Atmosphere Modeling Tool Evolution of Atmosphere Model • Solar System Planets & Moons ~ 1980’s (e.g., McKay et al. 1989) • Brown Dwarfs ~ 2000’s (e.g., Burrows et al. 2001) • Hot Jupiters & Other Giant Exoplanets ~ 2000’s (e.g., Fortney et al. -

![Arxiv:2001.00125V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 1 Jan 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5716/arxiv-2001-00125v1-astro-ph-ep-1-jan-2020-265716.webp)

Arxiv:2001.00125V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 1 Jan 2020

Draft version January 3, 2020 Typeset using LATEX default style in AASTeX61 SIZE AND SHAPE CONSTRAINTS OF (486958) ARROKOTH FROM STELLAR OCCULTATIONS Marc W. Buie,1 Simon B. Porter,1 et al. 1Southwest Research Institute 1050 Walnut St., Suite 300, Boulder, CO 80302 USA To be submitted to Astronomical Journal, Version 1.1, 2019/12/30 ABSTRACT We present the results from four stellar occultations by (486958) Arrokoth, the flyby target of the New Horizons extended mission. Three of the four efforts led to positive detections of the body, and all constrained the presence of rings and other debris, finding none. Twenty-five mobile stations were deployed for 2017 June 3 and augmented by fixed telescopes. There were no positive detections from this effort. The event on 2017 July 10 was observed by SOFIA with one very short chord. Twenty-four deployed stations on 2017 July 17 resulted in five chords that clearly showed a complicated shape consistent with a contact binary with rough dimensions of 20 by 30 km for the overall outline. A visible albedo of 10% was derived from these data. Twenty-two systems were deployed for the fourth event on 2018 Aug 4 and resulted in two chords. The combination of the occultation data and the flyby results provides a significant refinement of the rotation period, now estimated to be 15.9380 ± 0.0005 hours. The occultation data also provided high-precision astrometric constraints on the position of the object that were crucial for supporting the navigation for the New Horizons flyby. This work demonstrates an effective method for obtaining detailed size and shape information and probing for rings and dust on distant Kuiper Belt objects as well as being an important source of positional data that can aid in spacecraft navigation that is particularly useful for small and distant bodies. -

The Subsurface Habitability of Small, Icy Exomoons J

A&A 636, A50 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201937035 & © ESO 2020 Astrophysics The subsurface habitability of small, icy exomoons J. N. K. Y. Tjoa1,?, M. Mueller1,2,3, and F. F. S. van der Tak1,2 1 Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, Landleven 12, 9747 AD Groningen, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 2 SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Landleven 12, 9747 AD Groningen, The Netherlands 3 Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, Niels Bohrweg 2, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands Received 1 November 2019 / Accepted 8 March 2020 ABSTRACT Context. Assuming our Solar System as typical, exomoons may outnumber exoplanets. If their habitability fraction is similar, they would thus constitute the largest portion of habitable real estate in the Universe. Icy moons in our Solar System, such as Europa and Enceladus, have already been shown to possess liquid water, a prerequisite for life on Earth. Aims. We intend to investigate under what thermal and orbital circumstances small, icy moons may sustain subsurface oceans and thus be “subsurface habitable”. We pay specific attention to tidal heating, which may keep a moon liquid far beyond the conservative habitable zone. Methods. We made use of a phenomenological approach to tidal heating. We computed the orbit averaged flux from both stellar and planetary (both thermal and reflected stellar) illumination. We then calculated subsurface temperatures depending on illumination and thermal conduction to the surface through the ice shell and an insulating layer of regolith. We adopted a conduction only model, ignoring volcanism and ice shell convection as an outlet for internal heat. -

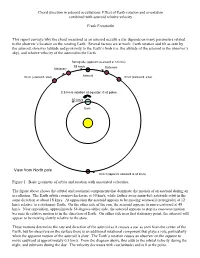

Chord Direction in Asteroid Occultations: Effect of Earth Rotation and Orientation Combined with Asteroid Relative Velocity

Chord direction in asteroid occultations: Effect of Earth rotation and orientation combined with asteroid relative velocity Frank Freestar8n This report conveys why the chord measured as an asteroid occults a star depends on many parameters related to the observer’s location on the rotating Earth. Several factors are at work: Earth rotation and tilt as seen by the asteroid, observer latitude and proximity to the Earth’s limb (i.e. the altitude of the asteroid in the observer’s sky), and relative velocity of the asteroid to the Earth. Retrograde (apparent westward at 12 km/s) 18 km/s Stationary Stationary Direct (eastward, slow) Asteroid Direct (eastward, slow) 0.5 km/s rotation at equator, 0 at poles 30 km/s Earth View from North pole Direct (apparent eastward at 48 km/s) Figure 1. Basic geometry of orbits and rotation with associated velocities. The figure above shows the orbital and rotational components that dominate the motion of an asteroid during an occultation. The Earth orbits counter-clockwise at 30 km/s, while farther away main-belt asteroids orbit in the same direction at about 18 km/s. At opposition the asteroid appears to be moving westward (retrograde) at 12 km/s relative to a stationary Earth. On the other side of the sun, the asteroid appears to move eastward at 48 km/s. Near opposition, approximately 54 degrees either side, the asteroid appears to stop its east-west motion because its relative motion is in the direction of Earth. On either side near that stationary point, the asteroid will appear to be moving slowly relative to the stars. -

Giant Planet / Kuiper Belt Flyby

Giant Planet / Kuiper Belt Flyby Amanda Zangari (SwRI) Tiffany Finley (SwRI) with Cecilia Leung (LPL/SwRI) Simon Porter (SwRI) OPAG: February 23, 2017 Take Away • New Horizons provided scientifically valuable exploration of the Kuiper Belt in the New Frontiers cost cap. • The Kuiper Belt is full of objects with a diverse range of stories that go beyond what we learned from Pluto. • Giant Planet flybys add scientific value to a Kuiper Belt mission • Found preliminary trajectory examples for high interest KBOs-- Haumea, Varuna, 2015 RR245 can be reached via Jupiter AND Saturn, Uranus or Neptune flyby in the 2030s. • To be a candidate New Frontiers mission, a 2 Giant planet+KBO mission must be endorsed by a decadal survey according to current rules. New Horizons Heritage NH Jupiter Encounter planned around Pluto flyby timing, which was dominated by achieving quadruple occultations, “interesting” side up. New Horizons Heritage Pluto flyby took advantage of Ecliptic crossing, enabling access to the cold classical belt (where 2014 MU69 is located). New Horizons Heritage 2014 MU69 discovered while in flight. Targeting was from spacecraft propulsion and took advantage of cold classical population density. Object is small, reddish ~40 km diameter. Saturn’s moons show incredible diversity NASA/JPL As do Uranus and Neptune Some Kuiper Belt Geography Where do we want to go? Getting there- JGA “anytime” New Horizons model: Fast Launch, Jupiter Flyby, Launch window every 11 years McGranaghan et al 2011 Can we go to more than just Jupiter? If so, where, what? New Horizons 2 • 2008 launch using New Horizons flight spares • Proposed Jupiter flyby, equinox flyby of Uranus, and flyby of (47171) 1999 TC36 (now know to be trinary). -

![Arxiv:1009.3071V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 16 Sep 2010 Eovdfo T Aetsa–R Oiae Yrflce Lig Reflected by Dominated AU– Star–Are 1 Parent About Al Its Than the from Larger Stars](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0638/arxiv-1009-3071v1-astro-ph-ep-16-sep-2010-eovdfo-t-aetsa-r-oiae-yr-ce-lig-re-ected-by-dominated-au-star-are-1-parent-about-al-its-than-the-from-larger-stars-540638.webp)

Arxiv:1009.3071V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 16 Sep 2010 Eovdfo T Aetsa–R Oiae Yrflce Lig Reflected by Dominated AU– Star–Are 1 Parent About Al Its Than the from Larger Stars

ApJ accepted Exoplanet albedo spectra and colors as a function of planet phase, separation, and metallicity Kerri L. Cahoy, Mark S. Marley NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035 [email protected] and Jonathan J. Fortney University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA 95064 ABSTRACT First generation space-based optical coronagraphic telescopes will obtain images of cool gas and ice giant exoplanets around nearby stars. The albedo spectra of exoplan- ets lying at planet-star separations larger than about 1 AU–where an exoplanet can be resolved from its parent star–are dominated by reflected light to beyond 1 µm and are punctuated by molecular absorption features. Here we consider how exoplanet albedo spectra and colors vary as a function of planet-star separation, metallicity, mass, and observed phase for Jupiter and Neptune analogs from 0.35 to 1 µm. We model Jupiter analogs with 1 and 3 the solar abundance of heavy elements, and Neptune analogs × × with 10 and 30 solar abundance of heavy elements. Our model planets orbit a solar × × analog parent star at separations of 0.8 AU, 2 AU, 5 AU, and 10 AU. We use a radiative- convective model to compute temperature-pressure profiles. The giant exoplanets are found to be cloud-free at 0.8 AU, possess H2O clouds at 2 AU, and have both NH3 arXiv:1009.3071v1 [astro-ph.EP] 16 Sep 2010 and H2O clouds at 5 AU and 10 AU. For each model planet we compute moderate resolution (R = λ/∆λ 800) albedo spectra as a function of phase. -

Journal Pre-Proof

Journal Pre-proof A statistical review of light curves and the prevalence of contact binaries in the Kuiper Belt Mark R. Showalter, Susan D. Benecchi, Marc W. Buie, William M. Grundy, James T. Keane, Carey M. Lisse, Cathy B. Olkin, Simon B. Porter, Stuart J. Robbins, Kelsi N. Singer, Anne J. Verbiscer, Harold A. Weaver, Amanda M. Zangari, Douglas P. Hamilton, David E. Kaufmann, Tod R. Lauer, D.S. Mehoke, T.S. Mehoke, J.R. Spencer, H.B. Throop, J.W. Parker, S. Alan Stern, the New Horizons Geology, Geophysics, and Imaging Team PII: S0019-1035(20)30444-9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114098 Reference: YICAR 114098 To appear in: Icarus Received date: 25 November 2019 Revised date: 30 August 2020 Accepted date: 1 September 2020 Please cite this article as: M.R. Showalter, S.D. Benecchi, M.W. Buie, et al., A statistical review of light curves and the prevalence of contact binaries in the Kuiper Belt, Icarus (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114098 This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. -

The Longevity of Water Ice on Ganymedes and Europas Around Migrated Giant Planets

The Astrophysical Journal, 839:32 (9pp), 2017 April 10 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aa67ea © 2017. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. The Longevity of Water Ice on Ganymedes and Europas around Migrated Giant Planets Owen R. Lehmer1, David C. Catling1, and Kevin J. Zahnle2 1 Dept. of Earth and Space Sciences/Astrobiology Program, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; [email protected] 2 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA, USA Received 2017 February 17; revised 2017 March 14; accepted 2017 March 18; published 2017 April 11 Abstract The gas giant planets in the Solar System have a retinue of icy moons, and we expect giant exoplanets to have similar satellite systems. If a Jupiter-like planet were to migrate toward its parent star the icy moons orbiting it would evaporate, creating atmospheres and possible habitable surface oceans. Here, we examine how long the surface ice and possible oceans would last before being hydrodynamically lost to space. The hydrodynamic loss rate from the moons is determined, in large part, by the stellar flux available for absorption, which increases as the giant planet and icy moons migrate closer to the star. At some planet–star distance the stellar flux incident on the icy moons becomes so great that they enter a runaway greenhouse state. This runaway greenhouse state rapidly transfers all available surface water to the atmosphere as vapor, where it is easily lost from the small moons. However, for icy moons of Ganymede’s size around a Sun-like star we found that surface water (either ice or liquid) can persist indefinitely outside the runaway greenhouse orbital distance. -

DISTANT Ekos

Issue No. 110 August 2017 ✤✜ s ✓✏ DISTANT EKO ❞✐ ✒✑ The Kuiper Belt Electronic Newsletter r✣✢ Edited by: Joel Wm. Parker [email protected] www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews CONTENTS News & Announcements ................................. 2 Abstracts of 10 Accepted Papers ........................ 3 Conference Information .............................. ....9 Newsletter Information .............................. 10 1 NEWS & ANNOUNCEMENTS LSST Solar System Science Collaboration Over its 10 year lifespan, the Large Synoptic Sky Survey Telescope (LSST) will catalog over 5 million Main Belt asteroids, almost 300,000 Jupiter Trojans, over 100,000 NEOs, and over 40,000 KBOs. Many of these objects will receive 100s of observations in multiple bandpasses. The LSST Solar System Science Collaboration (SSSC) is preparing methods and tools to analyze this data, as well as understand optimum survey strategies for discovering moving objects throughout the Solar System. The SSSC launched a new website. Check it out at http://www.lsstsssc.org , and please consider joining the collaboration if you’re an eligible researcher. If you have any questions, please contact the SSSC Co-Chairs, Meg Schwamb ([email protected]) and David Trilling ([email protected]). ................................................... ................................................. There were no new TNO discoveries announced since the previous issue of Distant EKOs, but there were 10 new Centaur/SDO discoveries: 2013 RQ98, 2013 RR98, 2013 UT15, 2014 UN225, 2015 GT50, 2015 -

Absolute Magnitude and Slope Parameter G Calibration of Asteroid 25143 Itokawa

Meteoritics & Planetary Science 44, Nr 12, 1849–1852 (2009) Abstract available online at http://meteoritics.org Absolute magnitude and slope parameter G calibration of asteroid 25143 Itokawa Fabrizio BERNARDI1, 2*, Marco MICHELI1, and David J. THOLEN1 1Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai‘i, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822, USA 2Dipartimento di Matematica, Università di Pisa, Largo Pontecorvo 5, 56127 Pisa, Italy *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 12 December 2008; revision accepted 27 May 2009) Abstract–We present results from an observing campaign of 25143 Itokawa performed with the 2.2 m telescope of the University of Hawai‘i between November 2000 and September 2001. The main goal of this paper is to determine the absolute magnitude H and the slope parameter G of the phase function with high accuracy for use in determining the geometric albedo of Itokawa. We found a value of H = 19.40 and a value of G = 0.21. INTRODUCTION empirical relation between a polarization curve and the albedo. Our work will take advantage by the post-encounter The present work was performed as part of our size determination obtained by Hayabusa, allowing a more collaboration with NASA to support the space mission direct conversion of the ground-based photometric Hayabusa (MUSES-C), which in September 2005 had a information into a physically meaningful value for the albedo. rendezvous with the near-Earth asteroid 25143 Itokawa. We Another important goal of these observations was to used the 2.2 m telescope of the University of Hawai‘i at collect more data for a possible future detection of the Mauna Kea. -

19790019903.Pdf

General Disclaimer One or more of the Following Statements may affect this Document This document has been reproduced from the best copy furnished by the organizational source. It is being released in the interest of making available as much information as possible. This document may contain data, which exceeds the sheet parameters. It was furnished in this condition by the organizational source and is the best copy available. This document may contain tone-on-tone or color graphs, charts and/or pictures, which have been reproduced in black and white. This document is paginated as submitted by the original source. Portions of this document are not fully legible due to the historical nature of some of the material. However, it is the best reproduction available from the original submission. Produced by the NASA Center for Aerospace Information (CASI) F I r 'ift t 10 FtdkUArRY 1977 LUNAR OCCULTATION OF URANUS. LIME DARKENING, AND POLAR BRIGHTENING AT 6900 R. R. RADICK AND W. C. TETLEY to V" A-CR-15x780) THR 10 FEBRUARY 1977 LUNAR N79-28074 LTATI0 1 OF URANr1S. RADIUS, LIMP ENING, ANn POLAR BRIGHTF, NINO AT 6900 A inois Univ.) 23 p HC A02/MF A01 rinclas CSCL 03A x,/89 29261 i, oil a a 1 • s^S^^1£l Z^lti^` Till: 10 FEBRUARY 1977 LUNAR OCCULTATION OF URANUS. ADIUS, LIMB DARKENING, AND POI.AR BRIGHTENING AT 6900 X. Richard R. Radick and William C. Tetley Astzonomy Department University of Illinois Uroana, IllLnois 61801 Manuscript pages: 16 Figures: 4 Tables: 2 RUNNING HEAD: LUNAR OCCULTATION OF URANUS DIRECT CORRESPONDENCE TO: Richard R. -

The Spherical Bolometric Albedo of Planet Mercury

The Spherical Bolometric Albedo of Planet Mercury Anthony Mallama 14012 Lancaster Lane Bowie, MD, 20715, USA [email protected] 2017 March 7 1 Abstract Published reflectance data covering several different wavelength intervals has been combined and analyzed in order to determine the spherical bolometric albedo of Mercury. The resulting value of 0.088 +/- 0.003 spans wavelengths from 0 to 4 μm which includes over 99% of the solar flux. This bolometric result is greater than the value determined between 0.43 and 1.01 μm by Domingue et al. (2011, Planet. Space Sci., 59, 1853-1872). The difference is due to higher reflectivity at wavelengths beyond 1.01 μm. The average effective blackbody temperature of Mercury corresponding to the newly determined albedo is 436.3 K. This temperature takes into account the eccentricity of the planet’s orbit (Méndez and Rivera-Valetín. 2017. ApJL, 837, L1). Key words: Mercury, albedo 2 1. Introduction Reflected sunlight is an important aspect of planetary surface studies and it can be quantified in several ways. Mayorga et al. (2016) give a comprehensive set of definitions which are briefly summarized here. The geometric albedo represents sunlight reflected straight back in the direction from which it came. This geometry is referred to as zero phase angle or opposition. The phase curve is the amount of sunlight reflected as a function of the phase angle. The phase angle is defined as the angle between the Sun and the sensor as measured at the planet. The spherical albedo is the ratio of sunlight reflected in all directions to that which is incident on the body.