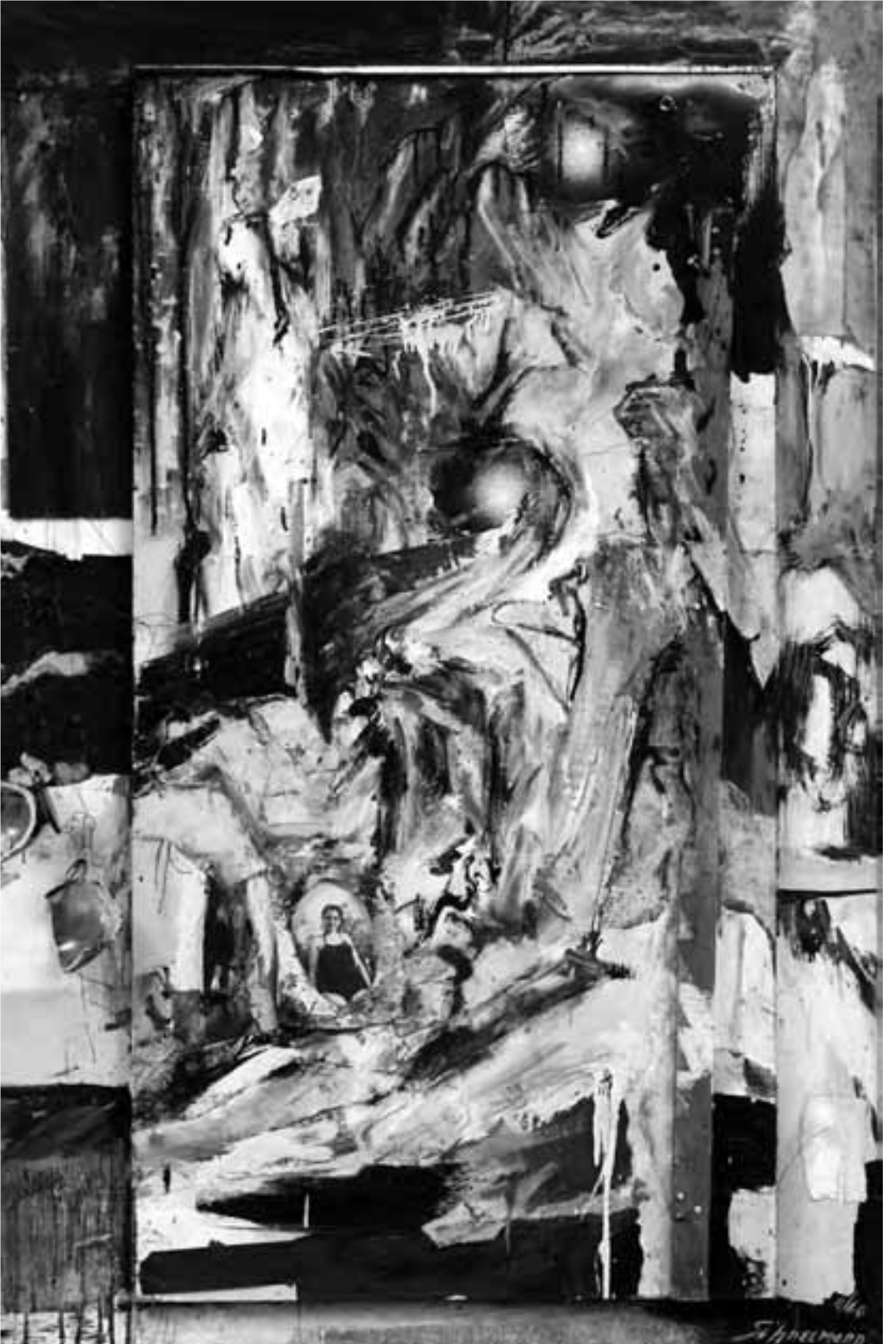

The Paintings of Carolee Schneemann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allan Kaprow: the Happenings Are Dead, Long Live the Happenings

1 ALLAN KAPROW: THE HAPPENINGS ARE DEAD, LONG LIVE THE HAPPENINGS Happenings are today's only underground avant-garde. Regularly, since 1958, the end of the Happenings has been announced--always by those who have never come near one--and just as regularly since then, Happenings have been spreading around the globe like some chronic virus, cunningly avoiding the familiar places and occurring where they are least expected. "Where Not To Be Seen: At a Happening," advised Esquire Magazine a year ago, in its annual two-page scoreboard on what's in and out of Culture. Exactly! One goes to the Museum of Modern Art to be seen. The Happenings are the one art activity that can escape the inevitable death-by-publicity to which all other art is condemned, because, designed for a brief life, they can never be over-exposed; they are dead, quite literally, every time they happen. At first unconsciously, then deliberately, they played the game of planned obsolescence, just before the mass media began to force the condition down the throats of the standard arts (which can little afford the challenge). For the latter, the great question has become "How long can it last?"; for the Happenings it always was "How to keep on going?". Thus, "underground" took on a different meaning. Where once the artist's enemy was the smug bourgeois, now he was the hippie journalist. In 1961 I wrote in an article, "To the extent that a Happening is not a commodity but a brief event, from the standpoint of any publicity it may receive, it may become a state of mind. -

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

August 19, 2022 John Dewey and the New Presentation of the Collection

Press contact: Anne Niermann Tel. +49 221 221 22428 [email protected] PRESS RELEASE August 20, 2020 – August 19, 2022 John Dewey and the New Presentation of the Collection of Contemporary Art at the Museum Ludwig Press conference: Wednesday, August 19, 2020, 11 a.m., press preview starting at 10 a.m. For the third time, the Museum Ludwig is showing a new presentation of its collection of contemporary art on the basement level, featuring fifty-one works by thirty-four artists. The works on display span all media—painting, installations, sculpture, photography, video, and works on paper. Artists: Kai Althoff, Ei Arakawa, Edgar Arceneaux, Trisha Baga, John Baldessari, Andrea Büttner, Erik Bulatov, Tom Burr, Michael Buthe, John Cage, Miriam Cahn, Fang Lijun, Terry Fox, Andrea Fraser, Dan Graham, Lubaina Himid, Huang Yong Ping, Allan Kaprow, Gülsün Karamustafa, Martin Kippenberger, Maria Lassnig, Jochen Lempert, Oscar Murillo, Kerry James Marshall, Park McArthur, Marcel Odenbach, Roman Ondak, Julia Scher, Avery Singer, Diamond Stingily, Rosemarie Trockel, Carrie Mae Weems, Josef Zehrer In previous presentations of contemporary art, individual artworks such as A Book from the Sky (1987–91) by Xu Bing and Building a Nation (2006) by Jimmie Durham formed the starting point for issues that determined the selection of the works. This time the work of the American philosopher John Dewey (1859–1952) and his international, still palpable influence in art education serve as a background for viewing the collection. The exhibition addresses the fundamental topics of the relationship between art and society as well as the production and reception of art. -

Ana Mendieta and Carolee Schneemann Selected Works 1966 – 1983

Irrigation Veins: Ana Mendieta and Carolee Schneemann Selected Works 1966 – 1983 On view April 30 – May 30, 2020 Ana Mendieta. Volcán, 1979, color photograph Carolee Schneemann, Study for Up to and Including Her Limits, 1973, color © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC photograph, photo credit: Antony McCall Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York Courtesy of the Estate of Carolee Schneemann, Galerie Lelong & Co., and Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York P·P·O·W, New York “These obsessive acts of re-asserting my ties with the earth are really a manifestation of my thirst for being.” Ana Mendieta Galerie Lelong & Co. and P·P·O·W present Irrigation Veins: Ana Mendieta and Carolee Schneemann, Selected Works 1966 – 1983, an online exhibition exploring the artists’ parallel histories, iconographies, and shared affinities for ancient forms and the natural world. Galerie Lelong and P·P·O·W have a history of collaboration and have co-represented Carolee Schneemann since 2017. This will be the first time the two artists are shown together in direct dialogue, an exhibition Schneemann proposed during the last year of her life. In works such as Mendieta’s Volcán (1979) and Schneemann’s Study for Up To and Including Her Limits (1973), both artists harnessed physical action to root themselves into the earth, establishing their ties to the earth and asserting bodily agency in the face of societal restraints and repression. Both artists identified as painters prior to activating their bodies as material; Mendieta received a MA in painting from the University of Iowa in 1972, and Schneemann received an MFA from the University of Illinois in 1961. -

Allan Kaprow

ALLAN KAPROW Born 1927 Atlantic City, NJ Died 2006 Encinitas, CA EDUCATION 1945-1949 New York University, New York 1947-1948 Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts, New York 1950-1952 Columbia University, New York 1957-1958 New School for Social Research, New York FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS 1967 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, New York 1962 William and Noma Copley Foundation Award, Chicago SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Allan Kaprow: Yard, Lévy Gorvy at SALON, Saatchi Gallery, London Allan Kaprow – Painting 1946-1957 – A Survey, Villa Merkel, Esslingen 2015 Allan Kaprow. Yard, NP3 (location M0Bi), Groningen Fluids, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin; also traveled to: Hamburger Bahnhof and Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin 2014 Allan Kaprow: Yard, The Hepworth Wakefield, Wakefield Sohm Display Window II. From Painting to Life: Allan Kaprow’s Happenings, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgart Allan Kaprow. Altres Maneres, Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona 2013 Allan Kaprow. Time Pieces, NBK Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin Allan Kaprow Stockroom, Sammlung Friedrichshof, Zurndorf Allan Kaprow Project, Sammlung Friedrichshof, Zurndorf Allan Kaprow Books and Posters, Christophe Daviet- Thery Livres et Editions d’ Artistes, Paris Fluids: A Happening by Allan Kaprow Reinvented by Art Theory & Practice, Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, Evanston 2011 Allan Kaprow in Deutschland: Wärme- und Kälteeinheiten, Zentralarchiv des internationalen Kunsthandels ZADIK, Cologne 2009 Allan Kaprow. Yard, Hauser & Wirth, New -

The Performativity of Performance Documentation

THE PERFORMATIVITY OF PERFORMANCE DOCUMENTATION Philip Auslander onsider two familiar images from the history of performance and body art: one from the documentation of Chris Burden’s Shoot (1971), the notori- ous piece for which the artist had a friend shoot him in a gallery, and Yves CKlein’s famous Leap into the Void (1960), which shows the artist jumping out of a second-story window into the street below. It is generally accepted that the first image is a piece of performance documentation, but what is the second? Burden really was shot in the arm during Shoot, but Klein did not really jump unprotected out the window, the ostensible performance documented in his equally iconic image. What difference does it make to our understanding of these images in relation to the concept of performance documentation that one documents a performance that “really” happened while the other does not? I shall return to this question below. As a point of departure for my analysis here, I propose that performance docu- mentation has been understood to encompass two categories, which I shall call the documentary and the theatrical. The documentary category represents the traditional way in which the relationship between performance art and its documentation is conceived. It is assumed that the documentation of the performance event provides both a record of it through which it can be reconstructed (though, as Kathy O’Dell points out, the reconstruction is bound to be fragmentary and incomplete1) and evidence that it actually occurred. The connection between performance and docu- ment is thus thought to be ontological, with the event preceding and authorizing its documentation. -

Types & Forms of Theatres

THEATRE PROJECTS 1 Credit: Scott Frances Scott Credit: Types & Forms of Theatres THEATRE PROJECTS 2 Contents Types and forms of theatres 3 Spaces for drama 4 Small drama theatres 4 Arena 4 Thrust 5 Endstage 5 Flexible theatres 6 Environmental theatre 6 Promenade theatre 6 Black box theatre 7 Studio theatre 7 Courtyard theatre 8 Large drama theatres 9 Proscenium theatre 9 Thrust and open stage 10 Spaces for acoustic music (unamplified) 11 Recital hall 11 Concert halls 12 Shoebox concert hall 12 Vineyard concert hall, surround hall 13 Spaces for opera and dance 14 Opera house 14 Dance theatre 15 Spaces for multiple uses 16 Multipurpose theatre 16 Multiform theatre 17 Spaces for entertainment 18 Multi-use commercial theatre 18 Showroom 19 Spaces for media interaction 20 Spaces for meeting and worship 21 Conference center 21 House of worship 21 Spaces for teaching 22 Single-purpose spaces 22 Instructional spaces 22 Stage technology 22 THEATRE PROJECTS 3 Credit: Anton Grassl on behalf of Wilson Architects At the very core of human nature is an instinct to musicals, ballet, modern dance, spoken word, circus, gather together with one another and share our or any activity where an artist communicates with an experiences and perspectives—to tell and hear stories. audience. How could any one kind of building work for And ever since the first humans huddled around a all these different types of performance? fire to share these stories, there has been theatre. As people evolved, so did the stories they told and There is no ideal theatre size. The scale of a theatre the settings where they told them. -

Online, Issue 15 and 16 July/Sept 2001 and July 2002

n.paradoxa online, issue 15 and 16 July/Sept 2001 and July 2002 Editor: Katy Deepwell n.paradoxa online issue no.15 and 16 July/Sept 2001 and July 2002 ISSN: 1462-0426 1 Published in English as an online edition by KT press, www.ktpress.co.uk, as issues 15 and 16, n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal http://www.ktpress.co.uk/pdf/nparadoxaissue15and16.pdf July 2001 and July/Sept 2002, republished in this form: January 2010 ISSN: 1462-0426 All articles are copyright to the author All reproduction & distribution rights reserved to n.paradoxa and KT press. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying and recording, information storage or retrieval, without permission in writing from the editor of n.paradoxa. Views expressed in the online journal are those of the contributors and not necessarily those of the editor or publishers. Editor: [email protected] International Editorial Board: Hilary Robinson, Renee Baert, Janis Jefferies, Joanna Frueh, Hagiwara Hiroko, Olabisi Silva. www.ktpress.co.uk n.paradoxa online issue no.15 and 16 July/Sept 2001 and July 2002 ISSN: 1462-0426 2 List of Contents Issue 15, July 2001 Katy Deepwell Interview with Lyndal Jones about Deep Water / Aqua Profunda exhibited in the Australian Pavilion in Venice 4 Two senses of representation: Analysing the Venice Biennale in 2001 10 Anette Kubitza Fluxus, Flirt, Feminist? Carolee 15 Schneemann, Sexual liberation and the Avant-garde of the 1960s Diary -

COURSE OUTLINE ETT205 Arts and Entertainment Management 3 3 15

Mercer County Community College COURSE OUTLINE ETT205 Arts and Entertainment Management 3 Course Number Course Title Credits 3 15 week Class or Laboratory Clinical or Studio Practicum, Course Length Lecture Work Hours Hours Co-op, Internship (15 week, Hours 10 week, etc.) None None_ Performance on an Examination/Demonstration Alternate Delivery Methods (Placement Score (if applicable); minimum CLEP score) (Online, Telecourse [give title of videos]) Required Materials: Sports and Entertainment Management, Kenneth Kaser & John R. Brooks, Jr. South-Western Thomson Publishing, 2005. ISBN: 0538438290 Managing a Nonprofit Organization in the Twenty-First Century, Third Revised Edition and Up, Thomas Wolf and Barbara Carter. Free Press, 1999. ISBN: 0684849909 Catalog Description: An introduction to common issues and best practices in the management of arts and entertainment organizations. Students will gain a basic understanding of business requirements and challenges in producing entertainment. Topics include common management structures in not-for-profit and for-profit arts and entertainment companies, marketing, public relations, fundraising, budgeting, and human resources. Legal concerns such as contracts, copyright, licensing, and royalties will also be discussed. Prerequisites: Corequisites: ETT101 or permission of the Coordinator None Last Revised: February 2017 Course Coordinator (name, email, phone extension): Scott Hornick, Assistant Professor of Music. (609) 570-3716; [email protected] Available Resources: - 1 - ETT205- Arts and Entertainment Management Directory of Theatre Training Programs: Profiles of College and Conservatory Programs throughout the United States. Dorset Theatre Festival and Colony House. Field, Shelly. (1992). Career Opportunities in Theater and the Performing Arts. Facts on File Publishing. Gassner, John. (1953). Producing the Play. Dryden Press. -

Oral History Interview with Suzanne Lacy, 1990 Mar. 16-Sept. 27

Oral history interview with Suzanne Lacy, 1990 Mar. 16-Sept. 27 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Suzanne Lacy on March 16, 1990. The interview took place in Berkeley, California, and was conducted by Moira Roth for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview has been extensively edited for clarification by the artist, resulting in a document that departs significantly from the tape recording, but that results in a far more usable document than the original transcript. —Ed. Interview [ Tape 1, side A (30-minute tape sides)] MOIRA ROTH: March 16, 1990, Suzanne Lacy, interviewed by Moira Roth, Berkeley, California, for the Archives of American Art. Could we begin with your birth in Fresno? SUZANNE LACY: We could, except I wasn’t born in Fresno. [laughs] I was born in Wasco, California. Wasco is a farming community near Bakersfield in the San Joaquin Valley. There were about six thousand people in town. I was born in 1945 at the close of the war. My father [Larry Lacy—SL], who was in the military, came home about nine months after I was born. My brother was born two years after, and then fifteen years later I had a sister— one of those “accidental” midlife births. -

Over Front Cover

Introduction: An art of the precarious Aaron Levy Edited Transcript: Master class with Carolee Schneemann Jordyn Feingold, Erica Levin, Aaron Levy, Emma Pfeiffer, Justin Reinsberg, Nicole Ripka, David Wilks, and Elliot Wolf sales rep: 1st ofa date: artist: cust: control: job #: Back Cover Front Cover rel #: Introduction: An art of the precarious there’s always these sort of tensions, of reference, but it’s a very succinct little Aaron Levy essay concerning the violence that has always been historically embedded against cats and women, the demonization of them both in early history and For many years, Carolee Schneemann’s work has foregrounded the relationship how that has its residual aspects still. between the artist’s body and the social body. Her art, her relationships, and her institutional negotiations have all foregrounded the fundamental relationship EL: I’ve been wondering about the repetition that happens in Mysteries of between the individual and socio-cultural conditions. She has enabled us at the Pussies, with the Finnish echo of what you say in English. Of course that Slought to think in similar terms, and to negotiate our position, identity, and probably has something to do with the context in which it was made, but for an practice in relation to the city and beyond. English audience there’s also something that I found really moving about how it takes these terrible accounts and turns them into something unrecognizable The word precariousness is often understood in terms of vulnerability, and if you don’t speak the language. There’s something really interesting about how the condition of being dependent on unknown conditions and uncertain that works in the piece that I found myself thinking about a lot afterwards. -

Fluxus: the Is Gnificant Role of Female Artists Megan Butcher

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College Summer 7-2018 Fluxus: The iS gnificant Role of Female Artists Megan Butcher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Contemporary Art Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Butcher, Megan, "Fluxus: The iS gnificant Role of Female Artists" (2018). Honors College Theses. 178. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/178 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract The Fluxus movement of the 1960s and early 1970s laid the groundwork for future female artists and performance art as a medium. However, throughout my research, I have found that while there is evidence that female artists played an important role in this art movement, they were often not written about or credited for their contributions. Literature on the subject is also quite limited. Many books and journals only mention the more prominent female artists of Fluxus, leaving the lesser-known female artists difficult to research. The lack of scholarly discussion has led to the inaccurate documentation of the development of Fluxus art and how it influenced later movements. Additionally, the absence of research suggests that female artists’ work was less important and, consequently, keeps their efforts and achievements unknown. It can be demonstrated that works of art created by little-known female artists later influenced more prominent artists, but the original works have gone unacknowledged.