Kurt Chirbas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

Crimestoppers Offer Reward for Info, on Sex Offender

VOLUME 30-NUMBER 46 SCOTCH PLAINS-FANWGOD, N.J. NOVEMBER *19, 1987 30 CENTS in flOFVTiKi'-i I-;,^TO-7, y^r-.m? it'tiSn /.V.W'^i'. ^Xs i /C^T- V . \> {'-I L.1& WANTED Crimestoppers offer reward for info, on sex offender Crimestoppers reward Hotline (654-TIPS) with forced his way in when she or call the Crimestoppers money is waiting for the information leading to ar- answered the doorbell, number without giving tipster who can provide in- rest and indictment in police said. your name," the detective formation in the case of a serious crime cases. Detective Howard said, adding that all infor- Fanwood woman who was Fanwood Police are in- Drewes, releasing a com- mation received will be sexually assaulted inside vestigating the Oct. 16 in- posite photo of the suspect handled on a strictly con- her home last month. cident, which occurred today, said the rapist was fidential basis. Law enforcement of- around 8 p.m. when a described as a black male, Detective Drewes said it ficials are hoping to enlist 31-year-old woman was about 45 years old, six- is very possible that there the aid of concerned attacked inside her living feet two inches tall, about may be similar cases which citizens, who can qualify room. The victim had just 180 lbs., clean shaven with have gone unreported. He for up to $5,000 in reward returned home from shop- grey specks in his hair and is urging women to report money by calling the ping and was sexually brown eyes with a yellow- any such attacks and re- 24-hour Crimestoppers assaulted by a man who ed condition consistent main anonymous if they with jaundice or hepatitis. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Lawyer-Bracket-2.Pdf

All-Time Best Fictonal Lawyer 1st Round 2nd Round 3rd Round 4th Round 5th Round 6th Round 5th Round 4th Round 3rd Round 2nd Round 1st Round 09-Dec 23-Dec 06-Jan 13-Jan 20-Jan 27-Jan 20-Jan 13-Jan 30-Dec 16-Dec 02-Dec 1 Lionel Hutz (Simpsons) Atticus Finch (To Kill a Mockingbird) 1 16 Steve Dallas (Bloom County comic strip) Michael Clayton (Michael Clayton) 16 8 Johnnie Cochran (South Park) Charles W. Kingsfield Jr. (The Paper Chase) 8 9 She-Hulk (Marvel Comics) Lesra Martin (The Hurricane) 9 5 Phoenix Wright (Gyakuten Saiban: Sono "Shinjitsu", Igiari!) Lt. Daniel Kaffee (A Few Good Men) 5 12 Foggy Nelson (Daredevil) Reggie Love (The Client) 12 4 Harvey Birdman (Harvey Birdman Attorney at Law) Henry Drummond (Inherit the Wind) 4 FINAL 13 Michelle the Lawyer (American Dad) Vinny Gambini (My Cousin Vinny) 13 6 Hyper-Chicken (Futerama) Mitch McDeere (The Firm) 6 11 Lawyer Morty (Rick and Morty) Mick Haller (The Lincoln Lawyer) 11 3 Harvey Dent (Batman) Elle Woods (Legally Blond) 3 14 Robin (DC Earth-Two) Martin Vail (Prinal Fear) 14 7 Blue-Haired Lawyer (Simpsons) Joe Miller (Philadelphia) 7 10 Judge Dredd (Judge Dredd) Hans Rolfe (Judgement at Nuremberg) 10 2 Matt Murdock (Daredevil) Erin Brockovich (Erin Brockovich) 2 15 Margot Yale (Gargoyles) Jake Brigance (A Time to Kill) 15 FINAL FOUR CHAMPION FINAL FOUR 1 Ben Matlock (Matlock) Barry Zuckerkorn (Arrested Development) 1 16 Denny Crane (Boston Legal) Ted Buckland (Scrubs) 16 8 Claire Kincaid (Law & Order) Bob Loblaw (Arrested Development) 8 9 Alan Shore (Boston Legal) Jackie Chiles (Seinfeld) 9 5 Sam Seaborn (West Wing) Clare Huxtable (The Cosby Show) 5 12 Harvey Specter (Suits) Charlie Kelly (Its Always Sunny in Philadelphia) 12 4 Horace Rumpole (Rumpole of the Bailey) Dan Fielding (Night Court) 4 13 Ally McBeal (Ally McBeal) Will Truman (Will & Grace) 13 6 Alicia Florrick (The Good Wife) Marshall Eriksen (How I Met Your Mother) 6 11 Arnie Becker (L.A. -

New Beginnings and Jenny Sullivan Present Jane Anderson's Food And

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Michael Berton October 17, 2019 Phone: (805) 963‐7777 x112 Email: [email protected] New Beginnings and Jenny Sullivan Present Jane Anderson’s Food and Shelter at the New Vic (SANTA BARBARA, CALIF.) – New Beginnings’ 50th anniversary celebration comes to an end this fall with a one‐night production of Food and Shelter by Jane Anderson at the New Vic on November 1st. As a leading provider of mental health, veteran and homeless services in Santa Barbara County, New Beginnings is proud to present the fanciful but heartrending story of a homeless family who spends the night at Disneyland. “Often we encounter community members who want to better understand how emotional instability, unemployment and poverty lead to homelessness,” shares Executive Director Kristine Schwarz. “So we have focused this past year on providing experiential opportunities that can give people a sense of what causes housing insecurity and what it feels like to be homeless, as well as on motivating them to think about how we can work together as a community to prevent and address it. Moreover, our hope is that Food and Shelter will enable people to understand the issue in systemic terms, while also considering the range of types of homelessness.” The production stars Joe Spano (NCIS, Apollo 13, NYPD Blue and Fracture), Eric Lange (Victorious, Lost, Narcos and The Bridge), Chris Butler (Designated Survivor, Rescue Dawn, The Good Wife, and King & Maxwell), and Faline England (9‐1‐1, The Mentalist, Station 19, and Valentine’s Day). Screenwriter Jane Anderson is an Emmy award‐winning writer and director whose many credits include The Wife, Olive Kitteridge, How to Make an American Quilt, Looking for Normal, It Could Happen to You, The Baby Dance, If These Walls Could Talk II, and The Positively True Adventures of the Alleged Texas Cheerleader Murdering Mom, for which Jane received an Emmy, Penn Award, and Writers Guild Award for best teleplay. -

The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 1 Full Episode

The good wife season 5 episode 1 full episode Crime · Alicia works on a Death Row appeal with Will and Diane before going off to start her own The Good Wife (–). / 1 user 1 critic Season 5 | Episode 1. Previous . HD. See full technical specs». Edit. The Good Wife: Everything is Ending - on on CBS All Access. Season 5: Episode 1 - Everything is Ending Full Episodes. Blue Bloods Video - Cutting Losses (Sneak Peek 1). Undo. Get Ready To Watch Even More Young Sheldon! - Undo. How To Watch Criminal Minds. Alicia works on a Death Row appeal with Will and Diane before going off to start her own firm with Cary, but people begin to suspect something is afoot. The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 1 The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 1 The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 1 The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 2 The Good. Watch The Good Wife: Everything Is Ending from Season 5 at Watch The Good Wife - Season 5, Episode 1 - Everything is Ending: Alicia tries to balance one final Watch Full Episodes: The Good Wife. Watch The Good Wife S05E01 Season 5 Episode 1. Season 1. watch all episodes The Good Wife Season. The Good Wife - Season 5 The fifth season of the legal drama begins with Alicia and Episode 1: Everything is Ending Episode 2: The Bit Bucket Episode 3: A. Trailer; Episode 1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10; 11; 12; 13; 14; 15; 16; 17; 18; 19 . Watch The Good Wife Season 5 putlocker9 Full Episode Online. -

The Good Wife Season 1 Episod 11 Free Download Watch the Good Wife Online

the good wife season 1 episod 11 free download Watch The Good Wife Online. You have found a great place to watch The Good Wife online. TV Fanatic has many options available for your viewing pleasure so watch The Good Wife online now! On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 22, Alicia must decide what she'll do next as a verdict is reached in Peter's trial on the series finale. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 21, as the trial unfolds, new accusations come out and Alicia works furiously to keep Peter from going back to jail. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 20, everything goes wrong at a party to celebrate Howard and Jackie's upcoming wedding while Eli asks Jason to investigate Peter. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 19, Peter faces possible arrest while Alicia and Lucca fly to Toronto to represent an NSA agent detained by customs. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 18, the power struggle at Lockhart, Agos & Lee reaches a boiling point, and Marissa is used as leverage in the case against Peter. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 17, the firm defends a father of a shooting victim when he puts up a billboard calling a gun store owner a murderer. What's Diane's plan for the firm? What does the FBI have on Peter? Check out our recap and review of The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 16. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 15, Eli hires Elsbeth Tascioni to find out why the FBI is after Peter while Alicia joins a secret panel of attorneys on a case. -

To Download The

FREE EXAM Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined Wellness Plans Extended Hours Multiple Locations www.forevervets.com4 x 2” ad Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTEYour Community Voice VED for 50 YearsRA RRecorecorPONTE VEDRA dderer entertainment EEXXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules, puzzles and more! December 3 - 9, 2020 Sample sale: INSIDE: Offering: 1/2 off Hydrafacials Venus Legacy What’s new on • Treatments Netflix, Hulu & • BOTOX Call for details Amazon Prime • DYSPORT Pages 3, 17 & 22 • RF Microneedling • Body Contouring • B12 Complex • Lipolean Injections • Colorscience Products • Alastin Skincare Judge him if you must: Bryan Cranston Get Skinny with it! (904) 999-0977 plays a troubled ‘Your Honor’ www.SkinnyJax.comwww.SkinnyJax.com Bryan Cranston stars in the Showtime drama series “Your Honor,” premiering Sunday. 1361 13th Ave., Ste.1 x140 5” ad Jacksonville Beach NowTOP 7 is REASONS a great timeTO LIST to YOUR HOMEIt will WITH provide KATHLEEN your home: FLORYAN List Your Home for Sale • YOUComplimentary ALWAYS coverage RECEIVE: while the home is listed 1) MY UNDIVIDED ATTENTION – • An edge in the local market Kathleen Floryan LIST IT becauseno delegating buyers toprefer a “team to purchase member” a Broker Associate home2) A that FREE a HOMEseller stands SELLER behind WARRANTY • whileReduced Listed post-sale for Sale liability with [email protected] UNDER CONTRACT - DAY 1 ListSecure® 904-687-5146 WITH ME! 3) A FREE IN-HOME STAGING https://www.kathleenfloryan.exprealty.com PROFESSIONAL Evaluation BK3167010 I will provide you a FREE https://expressoffers.com/exp/kathleen-floryan 4) ACCESS to my Preferred Professional America’s Preferred Services List Ask me how to get cash offers on your home! 5) AHome 75 Point SELLERS Warranty CHECKLIST for for Preparing Your Home for Sale 6) ALWAYSyour Professionalhome when Photography we put– 3D, Drone, Floor Plans & More 7) Ait Comprehensive on the market. -

GOOD WIFE by Robert King & Michelle King

THE GOOD WIFE by Robert King & Michelle King January 29, 2009 TEASER A VIDEO IMAGE of... ...a packed press conference. A lower-third chyron trumpets “Chicago D.A. Resigns” as the grim D.A. approaches a podium, his wife beside him. He clears his throat, reads: DAVID FOLLICK Good morning. An hour ago, I resigned as States Attorney of Cook County. I did this with a heavy heart and a deep commitment to fight these scurrilous charges. At the same time, I need time to atone for my private failings with my wife, Alicia, and our two children. Oh, one of those press conferences. Scandal. In the key of Elliott Spitzer. DAVID FOLLICK (40) is a back-slapping Bill Clinton: smart, funny, calculatedly seductive, and now at the end of his career. But he’s not our hero. Our hero is... ...his wife, ALICIA (late-30s) standing beside him. Pretty. Proper. She’s always been the good girl-- the good girl who became the good wife, then the good mom: devoted, struggling not to outshine her husband. We move in on her as we hear... DAVID FOLLICK (CONT’D) I want to be clear. I have never abused my office. I have never traded lighter sentences for either financial or sexual favors. Ugh. We suddenly enter the video, and we’re there with... Alicia as she looks out at the excited reporters, the phalanx of cameras all clicking, boring in on her. DAVID FOLLICK (CONT’D) But I do admit to a failure of judgment in my private dealings with these women. -

HELENA from the WEDDING Directed by Joseph Infantolino

HELENA FROM THE WEDDING Directed by Joseph Infantolino “Absorbing...deftly written and acted!” -- Jonathan Rosenbaum USA | 2010 | Comedy-Drama | In English | 89 min. | 16x9 | Dolby Digital Film Movement Press Contact: Claire Weingarten | 109 W. 27th Street, Suite 9B | New York, NY 10001 tel: (212) 941-7744 x 208 | fax: (212) 941-7812 | [email protected] Film Movement Theatrical Contact: Rebeca Conget | 109 W. 27th Street, Suite 9B | New York, NY 10001 tel: (212) 941-7744 x 213 | fax: (212) 941-7812 | [email protected] 1 SYNOPSIS Newlyweds Alex (Lee Tergesen) and Alice (Melanie Lynskey) Javal are hosting a weekend-long New Year’s Eve party for their closest friends at a remote cabin in the mountains. They expect Alex’s best friend Nick (Paul Fitzgerald), newly separated from his wife, to show up at the cabin with his girlfriend Lola. Alex and Nick’s childhood friend Don (Dominic Fumasa) is also set to arrive with his wife-of-many-years Lynn (Jessica Hecht), as are Alice’s pregnant friend Eve (Dagmara Dominczyk) and her husband Steven (Corey Stoll) Any thoughts of a perfect weekend are quickly thrown out the window as Nick arrives with only a cooler of meat and the news that he and Lola have recently called it quits. Don and Lynn show up a few minutes later deep in an argument. Finally, Eve and Steven make it to the cabin with a surprise guest in tow—Eve’s friend Helena, who was a bridesmaid with Alice at Eve’s wedding. With tensions running high at the cabin, Alex tries to approach the young and beautiful Helena. -

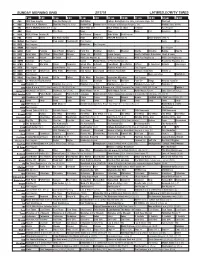

Sunday Morning Grid 2/17/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/17/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding College Basketball Ohio State at Michigan State. (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Day Hockey New York Rangers at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Hockey: Blues at Wild 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid American Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program 1 1 FOX Planet Weird Fox News Sunday News PBC Face NASCAR RaceDay (N) 2019 Daytona 500 (N) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Christina Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Grand Canyon Huell’s California Adventures: Huell & Louie 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN Jeffress Win Walk Prince Carpenter Intend Min.