The Author Is Dead, Long Live the Author - Alt Lit, Authorship, and the Objectification of the Self Through Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) PAUL SPARKS

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) Riley Keough, 26, is one of Hollywood’s rising stars. At the age of 12, she appeared in her first campaign for Tommy Hilfiger and at the age of 15 she ignited a media firestorm when she walked the runway for Christian Dior. From a young age, Riley wanted to explore her talents within the film industry, and by the age of 19 she dedicated herself to developing her acting craft for the camera. In 2010, she made her big-screen debut as Marie Currie in The Runaways starring opposite Kristen Stewart and Dakota Fanning. People took notice; shortly thereafter, she starred alongside Orlando Bloom in The Good Doctor, directed by Lance Daly. Riley’s memorable work in the film, which premiered at the Tribeca film festival in 2010, earned her a nomination for Best Supporting Actress at the Milan International Film Festival in 2012. Riley’s talents landed her a title-lead as Jack in Bradley Rust Gray’s werewolf flick Jack and Diane. She also appeared alongside Channing Tatum and Matthew McConaughey in Magic Mike, directed by Steven Soderbergh, which grossed nearly $167 million worldwide. Further in 2011, she completed work on director Nick Cassavetes’ film Yellow, starring alongside Sienna Miller, Melanie Griffith and Ray Liota, as well as the Xan Cassavetes film Kiss of the Damned. As her camera talent evolves alongside her creative growth, so do the roles she is meant to play. Recently, she was the lead in the highly-anticipated fourth installment of director George Miller’s cult- classic Mad Max - Mad Max: Fury Road alongside a distinguished cast comprising of Tom Hardy, Charlize Theron, Zoe Kravitz and Nick Hoult. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

Views Led to Her Getting a Position Teaching Poetry in the Creative Writing Masters Program at Hunter

BRETT L. ZELMAN’S MASTER THESIS BRETT L. ZELMAN Masters of Fine Arts in Creative Writing Cleveland State University May 2016 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN CREATIVE WRITING at the NORTHEAST OHIO MFA and CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May 2016 We hereby approve this thesis For Brett L. Zelman Candidate for the Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing degree Department of English, the Northeast Ohio MFA Program and CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY’S College of Graduate Studies by Thesis Chairperson, Professor Imad Rahman: _______________________________________________________________________ Department of English, May 4, 2016 Professor Mike Geither: _______________________________________________________________________ Department of English, May 4, 2016 Professor Eric Wasserman: _______________________________________________________________________ Department of English, May 4, 2016 _______________________________________________________________________ May 4, 2016 BRETT L. ZELMAN’S MASTER THESIS BRETT L. ZELMAN ABSTRACT This thesis is a work of fiction. It is a collection of short stories and one novel-in- progress. The work is written mostly in the literary realism genre along with some satirical aspects, satirizing pop culture and the millennial generation. Main themes are personal experience, familial dynamics and community. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………..…………………..…………………..………………….iii STORIES I. I SAW HER SITTING THERE………….…………………..………....…….1 II. SOME PEOPLE…...………..………..………..………..………..….……..28 -

87Th Academy Awards Reminder List

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 87TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT LAST NIGHT Actors: Kevin Hart. Michael Ealy. Christopher McDonald. Adam Rodriguez. Joe Lo Truglio. Terrell Owens. David Greenman. Bryan Callen. Paul Quinn. James McAndrew. Actresses: Regina Hall. Joy Bryant. Paula Patton. Catherine Shu. Hailey Boyle. Selita Ebanks. Jessica Lu. Krystal Harris. Kristin Slaysman. Tracey Graves. ABUSE OF WEAKNESS Actors: Kool Shen. Christophe Sermet. Ronald Leclercq. Actresses: Isabelle Huppert. Laurence Ursino. ADDICTED Actors: Boris Kodjoe. Tyson Beckford. William Levy. Actresses: Sharon Leal. Tasha Smith. Emayatzy Corinealdi. Kat Graham. AGE OF UPRISING: THE LEGEND OF MICHAEL KOHLHAAS Actors: Mads Mikkelsen. David Kross. Bruno Ganz. Denis Lavant. Paul Bartel. David Bennent. Swann Arlaud. Actresses: Mélusine Mayance. Delphine Chuillot. Roxane Duran. ALEXANDER AND THE TERRIBLE, HORRIBLE, NO GOOD, VERY BAD DAY Actors: Steve Carell. Ed Oxenbould. Dylan Minnette. Mekai Matthew Curtis. Lincoln Melcher. Reese Hartwig. Alex Desert. Rizwan Manji. Burn Gorman. Eric Edelstein. Actresses: Jennifer Garner. Kerris Dorsey. Jennifer Coolidge. Megan Mullally. Bella Thorne. Mary Mouser. Sidney Fullmer. Elise Vargas. Zoey Vargas. Toni Trucks. THE AMAZING CATFISH Actors: Alejandro Ramírez-Muñoz. Actresses: Ximena Ayala. Lisa Owen. Sonia Franco. Wendy Guillén. Andrea Baeza. THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 2 Actors: Andrew Garfield. Jamie Foxx. Dane DeHaan. Colm Feore. Paul Giamatti. Campbell Scott. Marton Csokas. Louis Cancelmi. Max Charles. Actresses: Emma Stone. Felicity Jones. Sally Field. Embeth Davidtz. AMERICAN REVOLUTIONARY: THE EVOLUTION OF GRACE LEE BOGGS 87th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AMERICAN SNIPER Actors: Bradley Cooper. Luke Grimes. Jake McDorman. Cory Hardrict. Kevin Lacz. Navid Negahban. Keir O'Donnell. Troy Vincent. Brandon Salgado-Telis. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

On Discovering Tao Lin ANNOUNCER

Melville House Publishing Co-founder Dennis Loy Johnson: On Discovering Tao Lin ANNOUNCER: Welcome to a podcast of Beyond the Book, a presentation of the not- for-profit, Copyright Clearance Center. Copyright Clearance Center is the world’s largest provider of copyright compliance solutions, through a wide range of innovative licensing services and comprehensive educational programs for authors, publishers, and their audiences in academia, business, and research institutions. For more information about Beyond the Book and Copyright Clearance Center, please go to www.beyondthebook.com. KENNEALLY: If you’re shopping for a little realism in your fiction, you might want to try Kmart. Kmart realism, that is, a school of novelist and short story writers that may or may not include Ann Beattie, Lorrie Moore, and Tao Lin, a 26-year-old Florida-raised, Chinese American writer now living in New York City. Welcome to Beyond the Book. I’m Chris Kenneally, your host. And we are looking ahead today to our annual visit to the Miami International Book Fair, and a discussion on Sunday, November 15th, at the Miami Book Fair with Tao Lin, author most recently of the novella, Shoplifting from American Apparel, published by Melville House just last month. To discuss Tao Lin, his new book, and his work, we welcome his editor, Dennis Loy Johnson. Dennis, thank you for joining Beyond the Book. JOHNSON: Hi, Chris. It’s great to be here. KENNEALLY: Well, it’s a pleasure to have you, and let’s tell people briefly about you and your work, because you are both a publisher and an author. -

The 20 Most Powerful Publicists in Hollywood

The 20 Most Powerful Publicists In Hollywood 20.) John Wentworth, Executive Vice President at CBS Television Distribution ● Clients: “Dr. Phil,” “The Doctors,” “Rachel Ray,” “Entertainment Tonight,” “The Insider,” “Inside Edition,” “Excused,” “Judge Judy,” “Judge Joe Brown,” “Wheel of Fortune,” “Jeopardy!” and “Swift Justice With Nancy Grace.” ● Why he makes the list: He oversees the publicity of 12 syndicated shows. Before his current position at CBS, Wentworth was EVP of Marketing and Communications for 11 years at Paramount Network Television. 19.) Nicole Perna, BWR ● Clients: Jessica Chastain, Chloe Moretz, Sharon Osbourne, Jenna Dewan, Lucy Hale, Johnny Galecki, Ryan Phillippe, Diane Kruger, Nikki Reed, Kellan Lutz. ● Why she makes the list: Perna, who has been at BWR since 2002, was promoted in June to help develop new strategies to support talent in a changing digital landscape. 18.) Jill Fritzo, Publicist at PMK*BNC ● Clients: Kim Kardashian, Khloe Kardashian, Kourtney Kardashian, Brooke Shields, Shannen Doherty, Denise Richards, Kristin Chenoweth, Vanessa Hudgens, Michael Strahan. ● Why she makes the list: She reps all three of the Kardashian sisters. Nothing else really needs to be said. Last year alone, the Kardashian empire pulled in roughly $65 million. 17.) Joy Fehily, Partner at Prime Public Relations and Communications ● Clients: Aaron Sorkin, Olivia Wilde, McG, Seth McFarlane and Graham King. ● Why she makes the list: Joy is the founding partner of PRIME Public Relations, which is a Los Angeles-based firm providing communications, brand management, marketing, strategic planning and social media services to the entertainment industry. 16.) Howard Bragman, Founder, Fifteen Minutes PR ● Clients: Stevie Wonder, Camille Grammer, Chaz Bono, Petra Ecclestone, Adrienne Maloof. -

P19.Qxp Layout 1

Thur Established 1961 Lifestyle WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 11, 2019 (From left to right) Golden Globe Ambassador Dylan Brosnan, Actress Dakota Fanning, Actor Tim Allen, Actress Susan Kelechi Watson and Golden Globe Ambassador Paris Brosnan pose on stage after the 77th Annual Golden Globe Awards nomi- nations announcement at the Beverly Hilton hotel in Beverly Hills. — AFP Photos ollywood disruptor Netflix dominated nations for Netflix on the comedy side. The stream- the Golden Globe nominations Monday er managed three film nods last year, for Mexican as its heart-wrenching divorce saga black-and-white drama “Roma.” The Golden H“Marriage Story” grabbed six nods Globes, which feature separate awards for dramas including best drama, kicking off the race for the and musicals/comedies, are known for favoring Oscars. The streaming giant, which has spent bil- star-studded movies that perform well at the box lions to lure the industry’s top filmmaking talent office, often with scant regard for critics’ reviews. and fund lavish awards season campaigns, Dark comic book tale “Joker,” which has trounced the traditional Tinseltown studios with a grossed over $1 billion worldwide despite polariz- whopping 17 film nominations. ing critics, was nominated for best drama, best “I’m not surprised by the dominance-I’m sur- actor (Joaquin Phoenix) and best director (Todd prised by how massive the dominance is,” Lorenzo Phillips). But the HFPA’s 90-odd members once Soria, president of the Hollywood Foreign Press again did not select any female directors, with Association, told AFP at the Beverly Hills ceremony. “Little Women” helmer Greta Gerwig notably “The announcements this morning are sort of like a absent. -

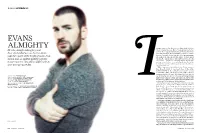

CHRIS EVANS Explains Can Handle.” and Evans Is Dead Serious

THE WELLWEll | cover story | EVaNS ALMiGHTY t’s the morning after the American Super Bowl and Chris He’s the straight-talking boy-next- Evans is feeling the pain. He’s a tried-and-true Boston fan and his New England Patriots just got thumped by their door who landed not one, but two plum most-hated rivals, the New York Giants. “Let’s not even touch that one,” he says to kick off our talk. “Yes, I’m in mourning. superhero parts at the height of comic-book The sadness, the rage, the fury, the denial – it’s more than I mania. But, as CHRIS EVANS explains can handle.” And Evans is dead serious. Because he still sees himself – despite his newfound success among both to joe yogerst, he’s still no different from moviegoers and critics – as a suburban Boston blue-collar kid who lives and dies with his sports teams, rather than an your average sports fan emerging movie star. What’s even more remarkable is that Evans wants to keep things that way: at arm’s length from all the razzle- dazzle in Hollywood. It’s a delicate balancing act – starring in blockbuster films and keeping a low profile – but he’s managed thus far. His name isn’t a household one and his PHOTOgrapHY / MICHAEL MULLER face doesn’t grace the cover of every other tabloid rag. But that creatiVE DirectiON AND STYLING / PariS LIBBY might be just a matter of time. Especially if the movies that STYLING / ILARIA URBiNATI, THE WALL GROUP he’s already got lined up prove as successful around the world GROOMING / JENN STREICHER, SOLO ARTISTS DIGITAL TECHNiciaN / RICKY RIDECOS as last year’s Captain America: The First Avenger. -

Shoplifting from American Apparel Free

FREE SHOPLIFTING FROM AMERICAN APPAREL PDF Tao Lin | 103 pages | 08 Oct 2009 | Melville House Publishing | 9781933633787 | English | Brooklyn, United States Shoplifting from American Apparel » Melville House Books Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Get A Shoplifting from American Apparel. Paperbackpages. Published September 15th by Melville House first published July 1st More Details Shoplifting from American Apparel Title. Other Editions 8. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Shoplifting from American Apparelplease sign up. Be the first to ask a question about Shoplifting from American Apparel. Shoplifting from American Apparel with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Start your review of Shoplifting from American Apparel. Jul 30, Lisa added it. View all 5 comments. May 09, Anita Dalton rated it did not like it Shelves: books-we-ownnon-fiction Shoplifting from American Apparel, fiction Shoplifting from American Apparel, autobiographybullshit-in-paper-form. Look, people have shit on those who write for a new zeitgeist pretty much since publishing evolved from the Gutenberg Press to a more accessible means of conveying ideas. Truman Capote demeaned Kerouac. Half the people I know would like to kill Holden Caulfield if he were a real human. I can tell you with no small amount of emphatic anger that this is not that, a woman long in her tooth clutching pearls at the antics of These Kids Today. -

Daniel Bruehl Biography

DANIEL BRUEHL BIOGRAPHY Award winning actor Daniel Bruehl has been involved in many critically acclaimed film and television projects and has garnered international recognition for his talent and versatility. Next, Daniel will shoot Kingsman The Great Game, directed by Matthew Vaughn and starring Ralph Fiennes, Charles Dance and Rhys Ifans. In April 2019 he will shoot “The Angel of Darkness”, which is a new limited series based on the sequel to best-selling author Caleb Carr’s “The Alienist”. In addition in the near future Daniel Bruehl and Luke Evans are reuniting for an untitled dramedy feature inspired by the 2006 French film Mon Meilleur Ami. In summer 2018 Daniel’s production company Amusement Park Films produced the film My Zoe which he featured in together with Julie Delpy and Gemma Arterton. My Zoe, which is written and directed by Julie Delpy, is the fascinating and confrontational story about the lengths to which a mother’s love goes for her child. In March 2018, Daniel has starred as activist ‘Wilfried Böse’ in drama feature Entebbe, opposite Rosamund Pike. Based on a true story, the film follows four hijackers who commandeer an airplane bound to Entebbe, Uganda in 1976 to free dozens of Palestinian and pro-Palestinian prisoners in Israel. On Netflix, Daniel can be seen in J.J. Abrams God Particle, about a group of astronauts fighting for survival. Julius Onah directs, and the feature also stars David Oyelowo, Gugu Mbatha-Raw, Elizabeth Debicki, and Chris O’Dowd. The Bad Robot picture was released worldwide by Netflix in February 2018. -

How Narrative Informs (Enforces/Challenges) Gender Roles

AP Literature 12: 3rd Quarter College-bound Essay Prompt focus: How narrative informs (enforces/challenges) gender roles. • This is a documented essay (in-text citations/Works Cited page) o 4-6 pages in MLA-8 standard with a Works Cited page o Premised on two narratives (novel/film) of Literary Merit o In-text citations from both narratives o In-text citations from at least 3 additional sources (articles provided, researched on your own, narratives from AP English 11 or AP Literature 12) o Works Cited page must have a minimum of 7 entries that you either cite or consider • Some ideas to consider: o 21st Century portrayal of gender in literature and/or film (compared to another era) – is gender becoming more fluid, or are the universal archetypes holding? o The roles of gender in storytelling (what male protagonists think/believe/act versus female protagonists think/believe/act) – traditional archetypes, new patterns? o How women write versus how men write? (about each other, life, etc…) o When big players in the industry take a stand – Marvel, DC, Disney, J.K. Rowling, Margaret Atwood, (there are lots!) – looking at their significant choices and how it affects the audience’s view of gender roles. o The modern protagonist – is the Hero’s Journey evolving? Finding Joe documentary. • Some angles to consider: o Jane Eyre as the avatar of female protagonist – revolutionary yet traditional – compare her to a modern female protagonist, also written by a woman. o F. Scott Fitzgerald’s portrayal of women in The Great Gatsby – sympathetic yet confined – compare to a modern male writer like John Green’s portrayal of women.