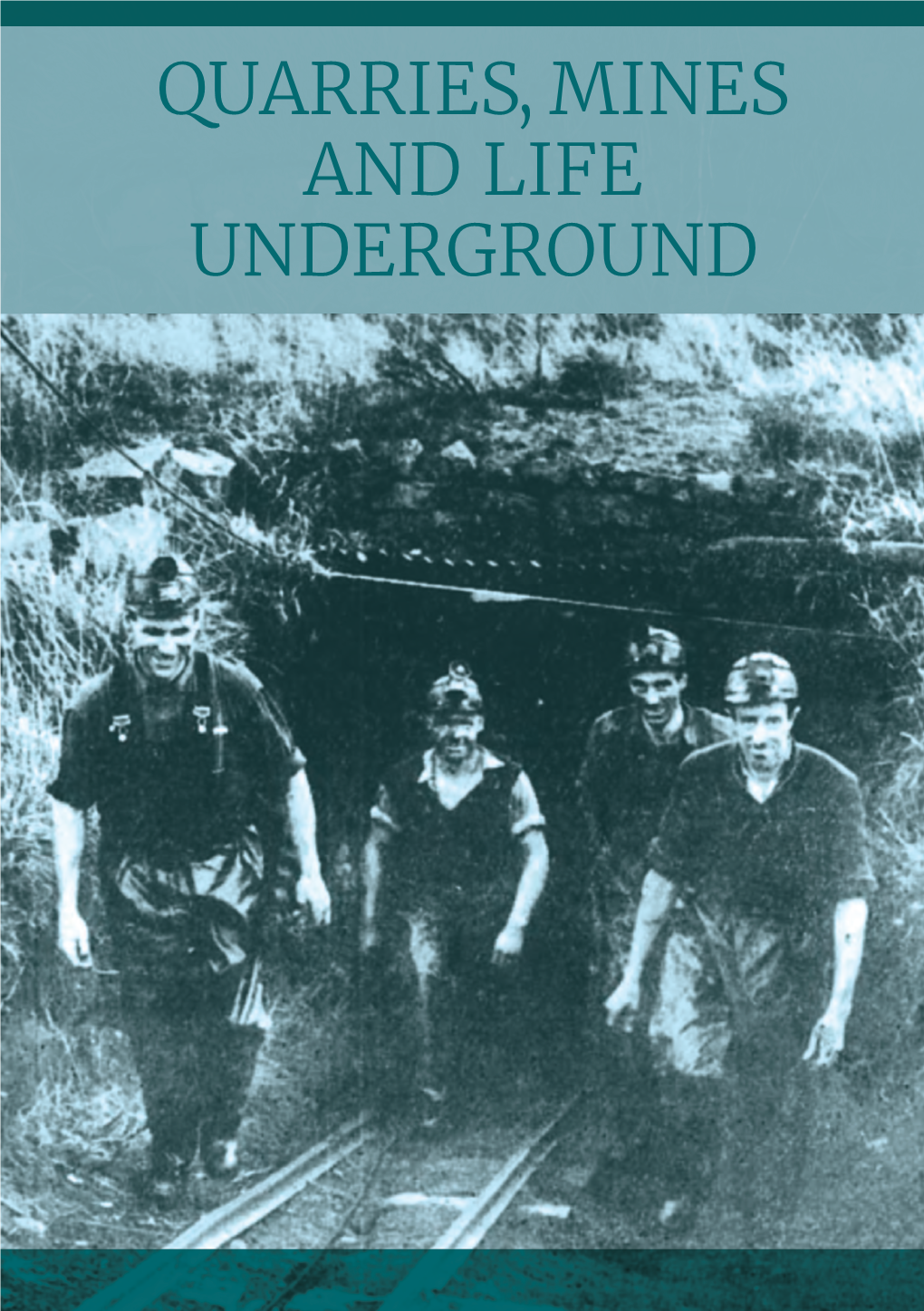

Quarries, Mines and Life Underground

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Falls Ward HB26/33/004 St, Comgall’S Primary School, Divis Street, Belfast, Co

THE BELFAST GAZETTE FRIDAY 25 JANUARY 2002 65 The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) Order 1991. Order 1991. District of Larne District of Larne Ballycarry Ward Ballycarry Ward HB06/05/013F HB06/05/049 Garden Turret at Red Hall, Ballycarry, Larne, Co. Antrim. 54 Main Street, Ballycarry, Carrickfergus, Co. Antrim, BT38 9HH. The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) Order 1991. Order 1991. District of Larne District of Larne Ballycarry Ward Ballycarry Ward HB06/05/013E HB06/05/036 Garden Piers at Red Hall, Ballycarry, Larne, Co. Antrim. Lime kilns at 9 Ballywillin Road, Glenoe, Larne, Co. Antrim. The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th Historic Monuments December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on the Order 1991. -

Causeway Coast Way

Causeway Coast Way Sweeping bays, sandy beaches, dramatic cliffs and world class natural heritage await you on the Causeway Coast Way RATHLIN Welcome to the PORTSTEWART ISLAND BALLYCASTLE Causeway Coast Way This superb, two-day walking route takes you along Northern Ireland's most celebrated coastline. High cliffs, secluded beaches and numerous historic and natural Benbane Head landmarks are just some of the 6 Sheep Island treats on offer. With frequent access Giant’s Causeway Carrick-a-rede Island White points and terrain suitable for all fit Dunseverick Park Bay Castle BALLINTOY walkers, this is one route you'll remember for years to come. The Skerries A2 PORTBALLINTRAE 7 Ramore Head 4 Clare A2 1 Wood BUSHMILLS B BALLYCASTLE B17 B17 A2 A2 Broughgammon PORTRUSH Wood East Strand, Portrush 17 4 B 4 PORTSTEWART A Ballycastle Moycraig 67 Forest 9 B Contents 2 Wood B B 1 A 8 8 6 Capecastle 04 - Section 1 5 Cloonty A Wood 2 Wood Portstewart to Portrush Mazes B 7 4 Wood 7 6 7 06 - Section 2 B1 2 B6 1 B Portrush to Portballintrae B 14 7 6 7 08 - Section 3 6 8 B67 B B Route is described in an clockwise direction. Portballintrae to Giant’s COLERAINE However, it can be walked in either direction. Causeway 10 - Section 4 Giant’s Causeway to Key to Map Dunseverick Castle SECTION 1 - PORTSTEWART TO PORTRUSH (10km) 12 - Section 5 Dunseverick Castle to SECTION 2 - PORTRUSH TO PORTBALLINTRAE (9.3km) Ballintoy Harbour SECTION 3 - PORTBALLINTRAE TO THE GIANT’S CAUSEWAY (4.3km) 14 - Section 6 Ballintoy Harbour to Ballycastle SECTION 4 - GIANT’S CAUSEWAY -

Invite Official of the Group You Want to Go

American Celebration of Music in Ireland Suggested Tour #7 (8 nights/10 days) Day 1 Depart via scheduled air service to Dublin, Ireland Day 2 Dublin / Belfast (D) Arrive in Meet your MCI Tour Manager, who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motorcoach Enjoy a panoramic tour of Dublin Option 1: Visit to Trinity College. Trinity College contains the Book of Kells, which dates from AD 800, making it one of the oldest books in the world Option 2: Visit to EPIC Ireland, the Irish Emigration Museum – A state of the art interactive museum experience located in the beautiful vaults of the 1820 Custom House building in Dublin’s Docklands. This is the original departure point for so many of Ireland’s emigrants. Nearly 37 Million U.S. Citizens list their heritage as Irish (Over 8 times the current population of Ireland). At EPIC, there are twenty themed galleries to find out why people left, who they were, see how they influenced the world they found, and experience the connection between their descendants and Ireland today Transfer to Belfast for late afternoon hotel check-in Evening 3-course Welcome Dinner at the hotel restaurant and overnight Belfast, capital since 1920 of the six counties of Northern Ireland, is an important industrial city and port. It lies beautifully situated on Belfast Lough in the northeast of Ireland, at the mouth of the River Lagan. The central pedestrianized area on the west bank of the River Lagan makes a pleasant place to stroll, with several department stores, shopping arcades, pubs and restaurants. -

Magherintemple Gate Lodge

Magherintemple Lodge Sleeps 2 adults and 2 chlidren – Ballycastle, Co Antrim Situation: Presentation: 1 dog allowed. Magherintemple Lodge is located in the beautiful seaside town of Ballycastle on the north Antrim Coast. It is a wonderful get-away for the family. There is a great feeling of quiet and peace, yet it is only 5 mins drive to the beach. The very spacious dining and kitchen room is full of light. The living room is very comfortable and on cooler evenings you can enjoy the warmth of a real log fire. Hidden away at the top of the house is a quiet space where you can sit and read a book, or just gaze out the window as you relax and enjoy the peace and quiet which surrounds you. 1 chien admis. La loge de Magherintemple est située dans la ville balnéaire de Ballycastle sur la côte nord d'Antrim. Elle permet une merveilleuse escapade pour toute la famille. Il s’en dégage un grand sentiment de calme et de paix et est à seulement 5 minutes en voiture de la plage. La salle à manger est très spacieuse et la cuisine est très lumineuse. Le salon est très confortable et les soirées fraîches, vous pouvez profiter de la chaleur d'un vrai feu de bois. Caché dans la partie supérieure de la maison, un espace tranquille où vous pouvez vous asseoir et lire un livre, ou tout simplement regarder par la fenêtre, pour vous détendre et profiter de la paix et du calme qui vous entoure. History: This is a beautiful gatelodge situated just outside the town of Ballycastle. -

Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report Local Development Plan 2030 - Draft Plan Strategy

Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report Local Development Plan 2030 - Draft Plan Strategy Have your say Mid and East Antrim Borough Council is consulting on the Mid and East Antrim Local Development Plan - Draft Plan Strategy 2030. Formal Consultation The draft Plan Strategy will be open for formal public consultation for a period of eight weeks, commencing on 16 October 2019 and closing at 5pm on 11 December 2019. Please note that representations received after the closing date on 11 December will not be considered. The draft Plan Strategy is published along with a range of assessments which are also open for public consultation over this period. These include a Sustainability Appraisal (incorporating a Strategic Environmental Assessment), a draft Habitats Regulations Assessment, a draft Equality (Section 75) Screening Report and a Rural Needs Impact Assessment. We welcome comments on the proposals and policies within our draft Plan Strategy from everyone with an interest in Mid and East Antrim and its continuing development over the Plan period to 2030. This includes individuals and families who live or work in our Borough. It is also important that we hear from a wide spectrum of stakeholder groups who have particular interests in Mid and East Antrim. Accordingly, while acknowledging that the list below is not exhaustive, we welcome the engagement of the following groups: . Voluntary groups . Business groups . Residents groups . Developers/landowners . Community forums and groups . Professional bodies . Environmental groups . Academic institutions Availability of the Draft Plan Strategy A copy of the draft Plan Strategy and all supporting documentation, including the Sustainability Appraisal Report, is available on the Mid and East Antrim Borough Council website: www.midandeastantrim.gov.uk/LDP The draft Plan Strategy and supporting documentation is also available in hard copy or to view during office hours, 9.30am - 4.30pm at the following Council offices: . -

ADAIR MANOR Ballymoney Road • Ballymena CONTEMPORARY HOMES for MODERN LIVING

CONTEMPORARY HOMES FOR MODERN LIVING ADAIR MANOR Ballymoney Road • Ballymena CONTEMPORARY HOMES FOR MODERN LIVING ADAIR MANOR Ballymoney Road • Ballymena ADAIR MANOR Adair Manor is a small exclusive new development of contemporary homes and apartments, situated just off the highly sought after Ballymoney Road, Ballymena. This unique new development will certainly appeal to purchasers who recognise quality and workmanship. With a superb range of modern semi detached homes, townhouses and apartments, all cleverly incorporated in a Fairhill Shopping Centre delightfully planned site layout, this landmark development offers a superb specification and introduces a whole new choice of stylish living to this part of the town. The local area boasts several excellent golf courses including Galgorm Castle and Ballymena Golf Club, rugby, football, Ballymena Bowling Club hockey and a bowling club plus the superb facilities at The Peoples Park and riverside walsk along the Braid. There are a number of excellent primary schools, nurseries, and grammar schools in Ballymena, some of which are within an easy walk, and the ideal location close to the town centre ensures that residents could not be better situated to enjoy all the superb The Braid Galgorm Castle Golf Club facilities that this wonderful historic town has to offer. The developers and architect have invested much time and effort into designing homes which are both functional and aesthetically pleasing. Combine this with living spaces which meet the needs of modern lifestyles and you get homes which are modern, both inside and outside.The craftsmanship, thought and attention to detail that has gone in to these homes will make them notable for their style and external finish, enhancing the beautiful ambience of the area, and providing a development that will maintain its appeal for decades. -

Planning Applications Validated for the Period 18/01/2021 to 22/01/2021 Reference Number Proposal Location Application Type

Planning Applications Validated For The Period 18/01/2021 to 22/01/2021 Reference Number Proposal Location Application Type LA02/2021/0038/RM Proposed dwelling on a Farm Adjacent to 126 Loughbeg Road Toomebridge Reserved Matters LA02/2021/0039/F Proposed erection of 17 dwellings comprising a mix of 1 detached and Lands immediately north north west of no.s 83 & 91- Full 16 semi-detached units, including construction of a section of the 117 (odds) Victoria Rise Victoria Link road scheme, associated parking and all other necessary site works. The proposal relates to an area of the over all scheme previously approved under LA02/2016/0919/F, namely site numbers 183a-198 formerly 2 detached and 14 semi-detached units. LA02/2021/0040/F Creation of 3 no. balconies to rear of building for apartments 3,5 & 7. Apartments 3 5 & 7 10 Chaine Memorial Road Full Window alterations to create access doors. Larne LA02/2021/0041/O New dwelling Site to rear of 216 Coast Road Ballygally Outline LA02/2021/0042/RM Replacement dwelling 40m approx. south east of 6 Cladytown Road Reserved Glarryford Matters LA02/2021/0043/F 2 storey side extension to dwelling 40 Fourtowns Manor Ahoghill Full LA02/2021/0045/O Site for dwelling on a farm 70M South-West of 99 Killagan Road Glarryford Outline LA02/2021/0046/LDP Construction of a new farm building adj to existing farm buildings. Adjacent to and North East of 40 Belfast Road LD Certificate Larne Proposed LA02/2021/0047/F Proposed new shed to provide Workshop/Office Space and Stores 47 Deerpark Road Glenarm Full LA02/2021/0048/F To erect a new 4 span 11,000 volt overhead line on wood pole From approx. -

Northern Ireland

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY RULES OF NORTHERN IRELAND 1996 No. 474 ROAD TRAFFIC AND VEHICLES Roads (Speed Limit) (No. 7) Order (Northern Ireland) 1996 Made - - - - 7th October 1996 Coming into operation 18th November 1996 The Department of the Environment, in exercise of the powers conferred on it by Article 50(4)(c) of the Road Traffic (Northern Ireland) Order 1981(1) and of every other power enabling it in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Roads (Speed Limit) (No. 7) Order (Northern Ireland) 1996 and shall come into operation on 18th November 1996. Speed restrictions on certain roads 2. The Department hereby directs that each of the roads and lengths of road specified in Schedule 1 shall be a restricted road for the purposes of Article 50 of the Road Traffic (Northern Ireland) Order 1981. Revocations 3. The provisions described in Schedule 2 are hereby revoked. Sealed with the Official Seal of the Department of the Environment on 7th October 1996. L.S. J. Carlisle Assistant Secretary (1) S.I.1981/154 (N.I. 1); see Article 2(2) for the definition of “Department” Document Generated: 2019-11-19 Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. SCHEDULE 1 Article 2 Restricted Roads 1. Ballynafie Road, Route A42, Ahoghill, from its junction with Glebe Road, Route B93, to a point approximately 510 metres south-west of that junction. -

Transcription of Ruth Mcfetridge's Death Book Sorted A

RUTH MCFETRIDGE'S DEATH BOOK Transcribed by Anne Shier Klintworth LAST NAME FIRST NAME RESIDENCE DATE OF DEATH NOTES ADAIR HARRY ESKYLANE 30-Jun-1979 ADAIR HETTIE (SCOTT) BELFAST ROAD, ANTRIM 30-Sep-1991 ADAIR INA ESKYLANE 23-Aug-1980 SAM MILLAR'S SISTER ADAIR JOSEPH TIRGRACEY, MUCKAMORE 31-Dec-1973 ADAIR WILLIAM TIRGRACEY, MUCKAMORE 18-Jan-1963 ADAMS CISSY GLARRYFORD 18-Feb-1999 WILLIAM'S HALF UNCLE (I BELIEVE SHE IS REFERING TO HER HUSBAND WILLIAM ADAMS DAVID BALLYREAGH 8-Sep-1950 MCFETRIDGE ADAMS DAVID LISLABIN 15-Sep-1977 AGE 59 ADAMS DAVID RED BRAE, BALLYMENA 19-Nov-1978 THORBURN'S FATHER ADAMS ENA CLOUGHWATHER RD. 4-Sep-1999 ISSAC'S WIFE ADAMS ESSIE CARNCOUGH 18-Dec-1953 ISSAC'S MOTHER WILLIAM'S GRANDFATHER (I BELIEVE SHE IS REFERING TO HER HUSBAND WILLIAM ADAMS ISSAC BALLYREAGH 23-Oct-1901 MCFETRIDGE ADAMS ISSAC CLOUGHWATHER RD. 28-Nov-1980 ADAMS JAMES SMITHFIELD, BALLYMENA 21-Feb-1986 ADAMS JAMES SENIOR SMITHFIELD PLACE, BALLYMENA 7-Jun-1972 ADAMS JIM COREEN, BROUGHSHANE 20-Apr-1977 ADAMS JOHN BALLYREAGH 21-May-1969 ADAMS JOHN KILLYREE 7-Nov-1968 JEANIE'S FATHER ADAMS JOSEPH CARNCOUGH 22-Aug-1946 Age 54, ISSAC'S FATHER ADAMS MARJORIE COREEN, BROUGHSHANE 7-Aug-2000 ADAMS MARY AGNES MAY LATE OF SPRINGMOUNT ROAD, SUNBEAM, GLARRYFORD 29-Apr-2000 WILLIAM'S GRANDMOTHER (I BELIEVE SHE IS REFERING TO HER HUSBAND WILLIAM ADAMS MARY J. BALLYREAGH 28-Feb-1940 MCFETRIDGE ADAMS MRS. ADAM BALLYKEEL 28-Jul-1975 JOAN BROWN'S MOTHER ADAMS MRS. AGNES KILLYREE 16-Aug-1978 JEANIE'S MOTHER ADAMS MRS. -

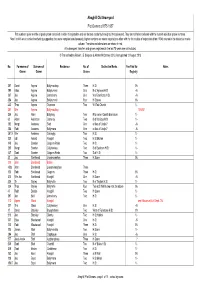

Ahoghill Old Graveyard Plot Owners C1875-1937

Ahoghill Old Graveyard Plot Owners c1875-1937 Plot numbers given are the original system compiled in order of registration and are located randomly throughout the graveyard. They are not to be confused with the current individual grave numbers. Nos.1 to 446 are in similar handwriting suggesting they were complied simutaneously, higher numbers are newer registrations often with the fee or date of registration (from 1904) entered in the distinctive marks column. Transfers and alterations are shown in red. All subsequent transfers and graves registered in the last 75 years are not included. © Transcribed by Robert J E Simpson & Alistair McCartney 2013, last updated 12 August 2013 No. Forename of Surname of Residence No. of Distinctive Marks Fee Paid for Notes Owner Owner Graves Registry 287 David Agnew Ballymacilroy Three H St 1/6 199 Ellen Agnew Ballylummin One N of Agnews H St -/6 267 Jno Agnew Limnaharry One W of Bamfords H St -/6 354 Jno Agnew Ballylummin Four H Stones 1/6 443 Thos Agnew Drumraw Two W. End Church 1/- 287 Wm Agnew Ballymacilroy 10/4/97 256 Jos. Allen Ballybeg Two N E corner Oneills Enclosure 1/- 62 Adam Anderson Carniney Two S of McCoys H St 1/- 282 Margt Andrews Slatt One at foot of Lindys? -/6 284 Robt Andrews Ballymena One at foot of Lindys? -/6 391.5 Wm Andrews Garvaghy Two H St 1/- 330 Isbl Arnold Ahoghill Two H St McKee 1/- 148 Jno Bamber Galgorm Parks Two H St 1/- 250 Margt Bamber Cullybackey Two S of Bambers H St 1/- 147 Saml Bamber Galgorm Parks Two S of H St 1/- 32 Jno Bankhead Lisnamurnahan Three H Stone 1/6 375 John Bankhead Ballee 453a John Bankhead Lisnamurnaghan Three 135 Robt Bankhead Galgorm Three H St 1/6 375 Wm Jno Bankhead Ahoghill One H Stone -/6 329 Th Bayley Ballynulto Two N of Taylors H St 1/- 304 Thos Bayley Ballynafie Four Two at S Wall & two next the above 1/6 47 Robt Beattie Ahoghill Two H Stone 1/- 297 Jno Bell Limnaharry Two H St 1/- 112 Agnes Black Ahoghill see Minutes of 4th Septr. -

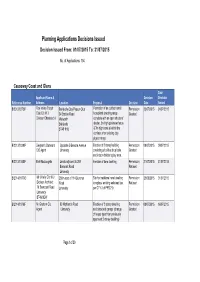

Planning Applications Decisions Issued Decision Issued From: 01/07/2015 To: 31/07/2015

Planning Applications Decisions Issued Decision Issued From: 01/07/2015 To: 31/07/2015 No. of Applications: 104 Causeway Coast and Glens Date Applicant Name & Decision Decision Reference Number Address Location Proposal Decision Date Issued B/2012/0273/F Roe Valley Target Ballykelly Clay Pigeon Club Formation of an outdoor small Permission 23/07/2015 24/07/2015 Club C/o W J 54 Station Road bore/pistol shooting range Granted Dickson Chartered A Walworth complete with an open shooters' Ballykelly shelter, 2m high perimeter fence BT49 9HU & 7m high bank all within the confines of an existing clay pigeon range B/2013/0038/F Deighan's Caravans Opposite 5 Benone Avenue Erection of 2 storey building Permission 08/07/2015 09/07/2015 C/O Agent Limavady. consisting of coffee shop/ cafe Granted and indoor childrens play area. B/2013/0148/F Mr E McLaughlin Lands adjacent to 209 Erection of farm dwelling Permission 21/07/2015 31/07/2015 Baranailt Road Refused Limavady B/2014/0177/O Mr J Kelly C/o W J 280m east of 114 Duncrun Site for traditional rural dwelling Permission 25/06/2015 01/07/2015 Dickson Architect Road to replace existing wallstead (as Refused 76 Seacoast Road Limavady per CTY 3 of PPS 21) Limavady BT49 9DW B/2014/0179/F Mr Graham C/o 80 Highlands Road Erection of 2 storey dwelling Permission 08/07/2015 16/07/2015 Agent Limavady and detached garage (change Granted of house type from previously approved 2 storey dwelling) Page 1 of 20 Planning Applications Decisions Issued Decision Issued From: 01/07/2015 To: 31/07/2015 No. -

Inventory of Closed Mine Waste Facilities in Northern Ireland. Phase 1 Data Collection and Categorisation

Inventory of closed mine waste facilities in Northern Ireland - Phase 2 Assessment Minerals and Waste Programme Commercial Report CR/14/031N BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MINERALS AND WASTE PROGRAMME COMMERCIAL REPORT CR/14/031 N Inventory of closed mine waste facilities in Northern Ireland - Phase 2 Assessment B Palumbo-Roe, K Linley, D Cameron, J Mankelow Contributor/editor T Johnston, MC Cowan The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database rights 2014. Ordnance Survey Licence No. 100021290. Keywords Mine waste Directive; Inventory; Northern Ireland. Bibliographical reference B PALUMBO-ROE, K LINLEY, D CAMERON, J MANKELOW. 2014. Inventory of closed mine waste facilities in Northern Ireland - Phase 2 Assessment. British Geological Survey Commercial Report, CR/14/031. 66pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. © NERC 2014. All rights reserved Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2014 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of our publications is available from BGS shops at British Geological Survey offices Nottingham, Edinburgh, London and Cardiff (Welsh publications only) see contact details below or shop online at www.geologyshop.com BGS Central Enquiries Desk Tel 0115 936 3143 Fax 0115 936 3276 The London Information Office also maintains a reference collection of BGS publications, including maps, for consultation.