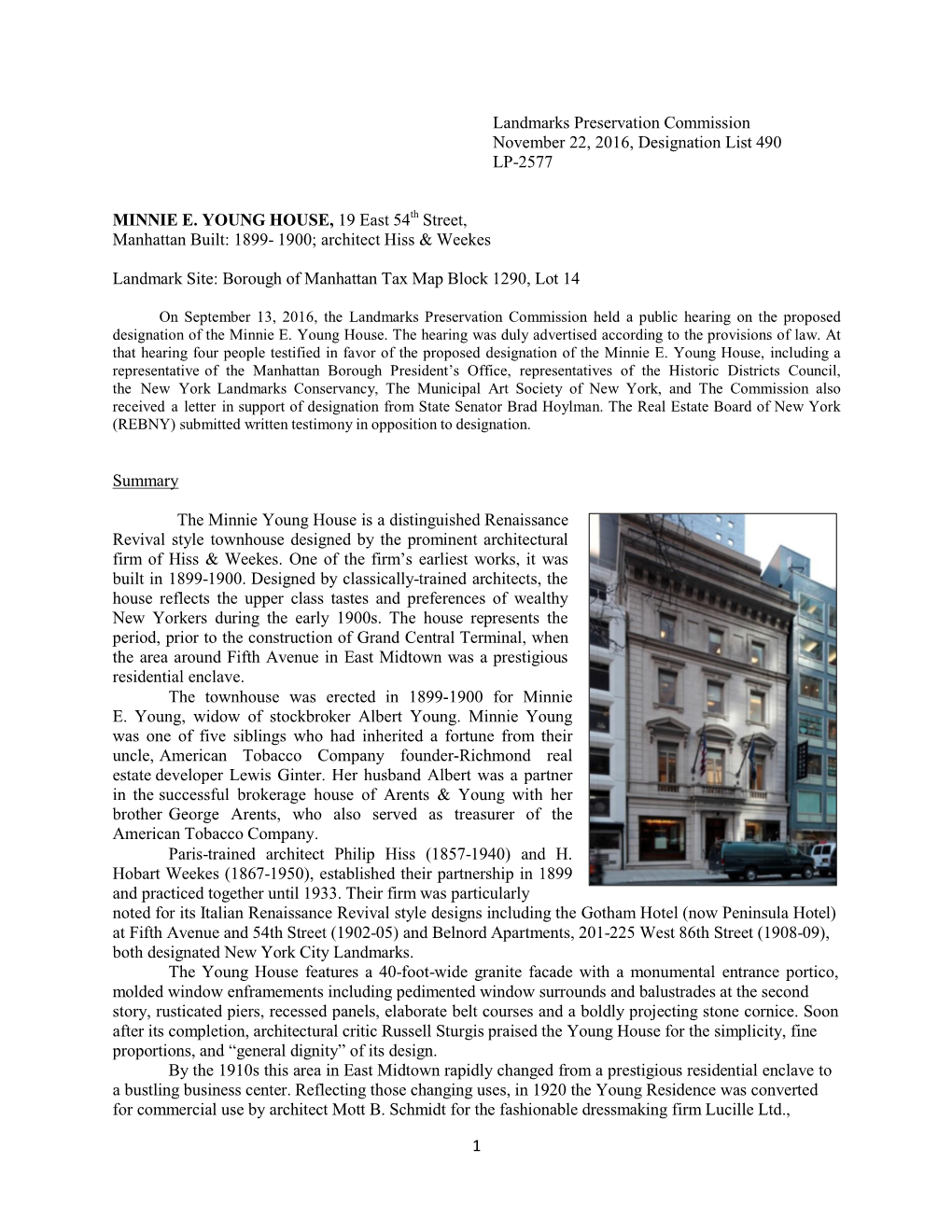

1 Landmarks Preservation Commission November

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Luxury Hotels, Resorts, Yachts, Mansions, Private Clubs, Museums

Luxury hotels, Resorts, Yachts, Mansions, Private clubs, Museums, Opera houses, restaurants RESORTS Boca Raton Resort & Club, Boca Raton, FL Bocaire Country Club, Boca Raton, FL Equinox Resort, Manchester Village, VT Hyatt Regency Aruba La Quinta Resort, La Quinta, CA Ojai Valley Inn & Spa, Ojai, CA Otesaga Resort Hotel, Cooperstown, NY Phoenician Resort, Phoenix, AZ Rosewood Mayakoba, Riviera Maya, Mexico Stoweflake Resort, Stowe, VT Westin La Paloma Resort, Tucson, AZ YACHTS Eastern Star yacht, Chelsea Piers, NYC Lady Windridge Yacht, Tarrytown, NY Manhattan cruise ship, Chelsea Piers, NYC Marika yacht, Chelsea Piers, NYC Star of America yacht, Chelsea Piers, NYC MANSIONS Barry Diller mansion, Beverly Hills, CA Boldt Castle, Alexandria Bay, NY 1 David Rockefeller mansion, Pocantico Hills, NY Neale Ranch, Saratoga, Wyoming Paul Fireman mansion, Cape Cod, MA Sam & Ronnie Heyman mansion, Westport, CT Somerset House, London The Ansonia, NYC The Mount, Lenox, MA Ventfort Hall, Lenox, MA Walter Scott Mansion, Omaha, NE (party for Warren Buffett) PRIVATE CLUBS American Yacht Club, Rye, NY The Bohemian Club, San Francisco The Metropolitan Club, NYC Millbrook Club, Greenwich, CT New York Stock Exchange floor and private dining room, NYC Birchwood Country Club, Westport, CT Cordillera Motorcycle Club, Cordillera, CO Cultural Services of the French Embassy, NYC Harold Pratt House, Council on Foreign Relations, Park Avenue, NYC Drayton Hall Plantation, Charleston, SC Tuxedo Club Country Club, Tuxedo Park, NY Fenway Golf Club, Scarsdale, NY Fisher Island, Miami Harvard Club, NYC Harvard Faculty Club, Cambridge, MA Bay Club at Mattaspoisett, Mattapoisett, MA Ocean Reef Club, Key Largo, FL Quail Hollow Country Club, Charlotte, NC Racquet and Tennis Club, Park Avenue, NYC Russian Trade Ministry, Washington DC Saugatuck Rowing Club, Westport, CT Shelter Harbor Country Club, Charlestown, RI St. -

Annual Report for the As a Result of the National Financial Environment, Throughout 2009, US Congress Calendar Year 2009, Pursuant to Section 43 of the Banking Law

O R K Y S T W A E T E N 2009 B T A ANNUAL N N E K M REPORT I N T G R D E P A WWW.BANKING.STATE.NY.US 1-877-BANK NYS One State Street Plaza New York, NY 10004 (212) 709-3500 80 South Swan Street Albany, NY 12210 (518) 473-6160 333 East Washington Street Syracuse, NY 13202 (315) 428-4049 September 15, 2010 To the Honorable David A. Paterson and Members of the Legislature: I hereby submit the New York State Banking Department Annual Report for the As a result of the national financial environment, throughout 2009, US Congress calendar year 2009, pursuant to Section 43 of the Banking Law. debated financial regulatory reform legislation. While the regulatory debate developed on the national stage, the Banking Department forged ahead with In 2009, the New York State Banking Department regulated more than 2,700 developing and implementing new state legislation and regulations to address financial entities providing services in New York State, including both depository the immediate crisis and avoid a similar crisis in the future. and non-depository institutions. The total assets of the depository institutions supervised exceeded $2.2 trillion. State Regulation: During 2009, what began as a subprime mortgage crisis led to a global downturn As one of the first states to identify the mortgage crisis, New York was fast in economic activity, leading to decreased employment, decreased borrowing to act on developing solutions. Building on efforts from 2008, in December and spending, and a general contraction in the financial industry as a whole. -

United States Bankruptcy Court Southern District Of

20-12117-mew Doc 2 Filed 09/10/20 Entered 09/10/20 22:11:29 Main Document Pg 1 of 32 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Chapter 11 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK In re: Case No. 20-12117 ( ) COSMOLEDO, LLC, et al.1 (Joint Administration Pending) Debtors. DECLARATION OF JOSÉ ALCALAY PURSUANT TO LOCAL BANKRUPTCY RULE 1007-2 AND IN SUPPORT OF THE DEBTORS’ CHAPTER 11 PETITIONS AND FIRST DAY PLEADINGS I, José Alcalay, hereby declare under penalty of perjury: Qualifications 1. I am the Chief Executive Officer of Cosmoledo, LLC (“Cosmoledo” and, together with its affiliated debtor subsidiaries, the “Debtors” or the “Company”), a restaurant operator in New York City. 2. I have served as the Company’s Chief Executive Officer since March 2020. I have also served as President of the Company from May 2019 to March 2020, Chief Financial Officer & Chief Operating Officer from March 2018 to May 2019 and Chief Financial Officer from September 2016 to March 2018. Prior to serving the Company, I held various senior financial and executive positions in different industries since 2002. I am an American citizen and hold the equivalent of a master’s degree in International Business Development from the University of 1 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases, along with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, include: Cosmoledo, LLC (6787); Breadroll, LLC, (3279); 688 Bronx Commissary, LLC (6515); 95 Broad Commissary, LLC (2335); 178 Bruckner Commissary, LLC (2581); 8 West Bakery, LLC (6421); NYC 1294 Third Ave Bakery, LLC (2001); 921 Broadway Bakery, LLC (2352); 1800 Broadway Bakery, LLC (8939); 1535 Third Avenue Bakery, LLC (1011); 2161 Broadway Bakery, LLC (2767); 210 Joralemon Bakery, LLC (4779); 1377 Sixth Avenue Bakery, LLC (9717); 400 Fifth Avenue Bakery, LLC (6378); 1400 Broadway Bakery, LLC (8529); 575 Lexington Avenue Bakery, LLC (9884); 685 Third Avenue Bakery, LLC (9613); 370 Lexington Avenue Bakery, LLC (0672); 787 Seventh Avenue Bakery, LLC (6846); 339 Seventh Avenue Bakery, LLC (1406); and 55 Hudson Yards Bakery, LLC (7583). -

Active Corporations: Beginning 1800

Active Corporations: Beginning 1800 DOS ID Current Entity Name 5306 MAGNOLIA METAL COMPANY 5310 BRISTOL WAGON AND CARRIAGE WORKS 5313 DUNLOP COAL COMPANY LIMITED 5314 THE DE-LON CORP. 5316 THE MILLER COMPANY 5318 KOMPACT PRODUCTS CORPORATION 5339 METROPOLITAN CHAIN STORES, INC. 5341 N. J. HOME BUILDERS CORPORATION 5349 THE CAPITA ENDOWMENT COMPANY 5360 ECLIPSE LEATHER CORP. 6589 SHERWOOD BROS. CO. 6590 BURLINGTON VENETIAN BLIND COMPANY 6593 CAB SALES COMPANY 6600 WALDIA REALTY CORPORATION 6618 GATTI SERVICE INCORPORATED 6628 HANDI APPLIANCE CORPORATION 6642 THE M. B. PARKER CONSTRUCTION COMPANY 6646 ALLIED BANKSHARES COMPANY 6651 SYRACUSE PURCHASING COMPANY, INC. Page 1 of 2794 09/28/2021 Active Corporations: Beginning 1800 Initial DOS Filing Date County Jurisdiction 06/08/1893 NEW YORK WEST VIRGINIA 05/16/1893 NEW YORK UNITED KINGDOM 09/17/1924 ERIE ONTARIO 09/18/1924 SARATOGA DELAWARE 09/19/1924 NEW YORK CONNECTICUT 09/12/1924 NEW YORK DELAWARE 10/27/1924 NEW YORK DELAWARE 10/27/1924 NEW YORK NEW JERSEY 10/24/1924 ALBANY OHIO 11/18/1924 NEW YORK NEW JERSEY 02/15/1895 ALBANY PENNSYLVANIA 02/16/1895 NEW YORK VERMONT 11/03/1927 NEW YORK DELAWARE 11/09/1927 NEW YORK DELAWARE 11/23/1927 NEW YORK NEW JERSEY 12/02/1927 NEW YORK DELAWARE 12/12/1927 NEW YORK OHIO 12/16/1927 NEW YORK NEW JERSEY 12/14/1927 NEW YORK GEORGIA Page 2 of 2794 09/28/2021 Active Corporations: Beginning 1800 Entity Type DOS Process Name FOREIGN BUSINESS CORPORATION EDWARD C. MILLER FOREIGN BUSINESS CORPORATION ALFRED HEYN FOREIGN BUSINESS CORPORATION DUNLOP COAL COMPANY LIMITED FOREIGN BUSINESS CORPORATION THE DE-LON CORP. -

Annual Meeting & Symposium Association for Preservation Technology

Disasters and How We Overcome Them 2021 Association for Annual Meeting Preservation & Symposium Technology February 26, 2021 Northeast Chapter Virtual Symposium APTNE 2021 Schedule of Events APTNE WELCOME ADDRESS 9:00AM - 9:10AM ANNUAL APTNE President, Rebecca Buntrock MEETING & Click or Scan for Q&A KEYNOTE PRESENTATION SYMPOSIUM #APTNE21 9:10AM - 10:00AM The Social Construction of Disaster History Don Friedman Addressing Graffiti on Masonry Substrates: 10:00AM - 10:35AM Taking a Sensitive Approach Casey Weisdock APTNE Living with Water: Adaption Processes, www.aptne.org 10:35AM - 11:00AM Heritage Conservation, and Conflicting Values aptne Shivali Gaikwad aptne_ DISASTERS AND HOW linkedin.com/ groups/8351626 11:00AM - 11:15AM Coffee Break (Breakout Rooms) WE OVERCOME THEM Architects of National Identity: an Analysis of Urbanization and 11:15AM - 11:40AM Historic Preservation of Minority Religious Venues in Shaxi, Yunnan Olivia McCarthy-Kelley Disasters come in various forms, whether they be a natural disaster, a man-made disaster, or a disastrous situation. In preservation, we deal Protecting Our Diplomatic Structures: A Seismic Program Review 11:40AM - 12:15PM with each of these disasters, whether it be from planning to prevent them, Shane Maxemow and David Keller investigating the aftermath, or in overcoming them and coming out better than before. Each situation is defined in how we approach the disaster CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS 12:15PM - 12:25PM and each of us is judge d in how we react. In a time that is currently fraught APTNE Vice President, Helena Currie with various global disasters, each of us is challenged to move above and beyond, bringing our history and our buildings with us. -

City Record Edition

3601 VOLUME CXLIII NUMBER 168 TUESDAY, AUGUST 30, 2016 Price: $4.00 Health and Mental Hygiene . 3610 Agency Chief Contracting Officer . 3610 THE CITY RECORD TABLE OF CONTENTS Housing Authority ��������������������������������������3610 BILL DE BLASIO Mayor PUBLIC HEARINGS AND MEETINGS Supply Management . 3610 City Planning Commission . 3601 Housing Preservation and Development ��� 3611 LISETTE CAMILO Commissioner, Department of Citywide Landmarks Preservation Commission ������3606 Maintenance . 3611 Administrative Services PROPERTY DISPOSITION Information Technology and ELI BLACHMAN Citywide Administrative Services . 3608 Telecommunications . 3611 Editor, The City Record Office of Citywide Procurement . 3608 Contracts and Procurement . 3611 Police ������������������������������������������������������������3608 Published Monday through Friday except legal Parks and Recreation . 3612 holidays by the New York City Department of PROCUREMENT Police ������������������������������������������������������������3612 Citywide Administrative Services under Authority Administration for Children’s Services . 3609 of Section 1066 of the New York City Charter. Equipment . 3612 Aging ������������������������������������������������������������3609 Subscription $500 a year, $4.00 daily ($5.00 by Probation . 3612 mail). Periodicals Postage Paid at New York, N.Y. Contract Procurement and Support POSTMASTER: Send address changes to AGENCY RULES Services . 3609 THE CITY RECORD, 1 Centre Street, 17th Floor, New York, N.Y. 10007-1602 City University ��������������������������������������������3609 -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX ABC Television Studios 152 Chrysler Building 96, 102 Evelyn Apartments 143–4 Abyssinian Baptist Church 164 Chumley’s 66–8 Fabbri mansion 113 The Alamo 51 Church of the Ascension Fifth Avenue 56, 120, 140 B. Altman Building 96 60–1 Five Points 29–31 American Museum of Natural Church of the Incarnation 95 Flagg, Ernest 43, 55, 156 History 142–3 Church of the Most Precious Flatiron Building 93 The Ansonia 153 Blood 37 Foley Square 19 Apollo Theater 165 Church of St Ann and the Holy Forward Building 23 The Apthorp 144 Trinity 167 42nd Street 98–103 Asia Society 121 Church of St Luke in the Fields Fraunces Tavern 12–13 Astor, John Jacob 50, 55, 100 65 ‘Freedom Tower’ 15 Astor Library 55 Church of San Salvatore 39 Frick Collection 120, 121 Church of the Transfiguration Banca Stabile 37 (Mott Street) 33 Gangs of New York 30 Bayard-Condict Building 54 Church of the Transfiguration Gay Street 69 Beecher, Henry Ward 167, 170, (35th Street) 95 General Motors Building 110 171 City Beautiful movement General Slocum 70, 73, 74 Belvedere Castle 135 58–60 General Theological Seminary Bethesda Terrace 135, 138 City College 161 88–9 Boathouse, Central Park 138 City Hall 18 German American Shooting Bohemian National Hall 116 Colonnade Row 55 Society 72 Borough Hall, Brooklyn 167 Columbia University 158–9 Gilbert, Cass 9, 18, 19, 122 Bow Bridge 138–9 Columbus Circle 149 Gotti, John 40 Bowery 50, 52–4, 57 Columbus Park 29 Grace Court Alley 170 Bowling Green Park 9 Conservatory Water 138 Gracie Mansion 112, 117 Broadway 8, 92 Cooper-Hewitt National Gramercy -

THE ANSONIA HOTEL, 2101-2119 Broadway, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission March 14, 1972, Number 1 LP-0285 THE ANSONIA HOTEL, 2101-2119 Broadway, Borough of Manhattan. Begun 1899, completed 1904; architect Paul E. M. DuBoy. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1165, Lot 20. On April 28, 1970, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Ansonia Hotel and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 13). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Two witnesses spoke in favor of designation. The owner opposed .it. Subsequent to the hearing the Commission has received 53 letters from individuals and organizations and petitions signed by approximately 25,770 persons favoring designation. It has also received a petition signed by 11 persons opposing designation. DESCRIPTION ~~D ANALYSIS This apartment-hotel in the grand French Beaux Arts style occupies the entire blockfront on the ,.,est side of Broadway bet•reen 73rd and 74th Streets. It rises on its conspicuous site to a height of seventeen stories. Built at the turn of the century, with over three hundred suites, it was at that time one of the largest apartment-hotels in the world. The Ansonia is a symbol of an era of opulence and elegance, and still stands as one of the truly grand buildings of Manhattan's West Side. The most striking features of this vast structure are the corner towers on Broadway, with their domes and railings, which rise slightly above and reptat the theme of the three story convex mansard roof that cr-owns the building. -

NEWS of the FOUR COUNTIES BORDERING SAN FRANCISCO BAY ~ " — I.* LE BEUF INCOURT Jjrev

8 THE S^lF^^ NEWS OF THE FOUR COUNTIES BORDERING SAN FRANCISCO BAY ~ " — i.* LE BEUF INCOURT jjRev. George H.Wilkins, MEN URGE VOTE ON WILDMANWORRIES RICH STRIKE MADE VANDALSATWORK PRATT&BECKER FOR EMBEZZLING Who Resigns Pastorate EQUAL SUFFRAGE OCEAN VIEWWOMEN ATMOORES CREEK IN JEWISH TEMPLE REFUSED LICENSE Former Cashier of Hale Bros. Is Alameda County League Secures Police Guard Boswell's Ranch to Important Discovery Is Made Sacred Articles Torn From Altar Secretary of Y. M. C. A. an* Having His Preliminary Signatures to Petition to : Track Dweller in Hills Near Milletts^ Station Scattered Over Floor Residents in Neighborhood ' Examination State Legislature North of Berkeley in Nevada of tdince . Protest Against Dive — tand OAKLAND,Dec. ZO. The preliminary OAKLAND. Dec. 30.—The equal suf- VBERKELET,' Dec 30.—A wild A story is printed- by ihe Round "The vandals who in the last few The application of Pratt & Becker reopen notorious the examination of Alfred A. Le Beuf, for- frage league of Aldmeda county will who « frequents the neighborhood of Mountain Nugget concerning ••- the re- weeks have committed depredations in to the dive at churches, of iiason and O'Farrell streets i a petition legislature ,;Vlew - creek, both Protestant and Catholic corner mer casMcr of Halo Bros.' Oakland send to the state Ocean has eluded all efforts of cent discoveries at Moores denied by the police commissioners ?20,- as Ifto complete their demonstration of |was store, who is accused of stealing asking that a constitutional amend- the police to capture him and, the wom- which Is situated; about a -•dbnen , contempt last night, but not without an exchange from; miie3 for all creeds and houses of I "00 from hi? former employers, on the ment to enfranchise women be sub- en" in the vicinity of Boswell's ranch Round Mountain. -

Interim Report

Interim Report Prepared By: DPZ Partners With: Gianni Longo & Associates Robert Orr & Associates CDM Smith The Williams Group Urban3 Good Earth Advisors Prepared For: City of Derby, CT • November 11, 2016 1:45 AM Page Intentionally Blank LISTENING TO THE COMMUNITY ........................... 5 Historic Context.........................................................54 Historic Maps .......................................................54 Stakeholder Interviews ............................................... 7 Historic Images ....................................................55 Overview ................................................................ 7 What We Heard ...................................................... 7 Views of the Site ........................................................58 Preliminary considerations .................................10 Scale Comparisons ...................................................60 Community Voices ....................................................11 Darien, CT .............................................................60 Overview ...............................................................11 Milford, CT ............................................................61 A. Strong & Weak Places: Mapping ...................11 Southport Green, Southport, CT ........................61 Bethesda Row, Bethesda, MD ............................62 Community Voices: Strong Places ..........................12 Rockville Town Center, MD .................................62 Mapping ...............................................................12 -

315 West 82Nd Street BROWNSTONE for SALE

315 West 82nd Street BROWNSTONE FOR SALE - 1 - Table of CONTENTS 03 04 05 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PROPERTY LOCATION SPECIFICATIONS 06 07 08 AS SEEN IN INCOME AND EXPENSES THE NEIGHBORHOOD THE NEW YORK TIMES 09 THE FUTURE - 2 - Executive Summary 315 WEST 82ND STREET This turn of the century brick and terracotta brownstone with large bay windows and multiple outdoor spaces is on a tree lined street of well maintained row houses. This is a fantastic opportunity to purchase a 10-unit apartment building (all Free Market) in the heart of Upper West Side and convert to live with income or create one magnificent residence. 315 West 82nd Street is one of five contiguous Romanesque Revival Row Houses - and still standing! Built and designed in 1887 - 1888 by the prolific team of Berg & Clark, this is a rare opportunity to live on a stunning expanse of late 19th century row houses with Beaux-Art flair. 315 West 82nd Street is all that remains to be developed as the others (307, 309, 311 & 313 West 82nd Street) have been converted into co-op apartments. *** Mortgage with First Republic at 3.65% due 6/2030 for $2,741,668. The building consists of three 2-bedroom apartments, six 1-bedroom apartments, and 1 studio apartment. Highlights of the units include the pre-war charms of exposed brick in the units. The penthouses include access to the roof and a backyard is available for the first floor. The interior photos show the wainscoting, wood banister, as well as an apartment on the penthouse level with outdoor space, high ceilings, hardwood floors. -

2101 Broadway – the Ansonia Hotel, Borough of Manhattan

March 23, 2021 Name of Landmark Building Type of Presentation Month xx, year Public Hearing The current proposal is: Preservation Department – Item 4, LPC-21-03327 2101 Broadway – The Ansonia Hotel, Borough of Manhattan How to Testify Via Zoom: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81918829973?pwd=b21lWUNITHBGNnFiK1VlMjdCcFduZz09 Note: If you want to testify on an item, join the Webinar ID: 819 1882 9973 Zoom webinar at the agenda’s “Be Here by” Passcode: 262330 time (about an hour in advance). When the By Phone: Chair indicates it’s time to testify, “raise your 1 646-558-8656 hand” via the Zoom app if you want to speak US (New York) 877-853-5257 (Toll free) (*9 on the phone). Those who signed up in US 888 475 4499 (Toll free) advance will be called first. The Ansonia . Upper West Side Endoscopy . Joint Venture Outpatient Endoscopy Center . Mount Sinai Ambulatory Ventures . Merritt Healthcare Holdings March 3, 2021 1 Area of work 3 Area of work 4 Area of work 5 Area of work Existing storefront 6 1 2 3 Existing conditions . Existing Ground Level Entrances - There are 9 retail store fronts and 2 residential entrances on the ground floor of the Ansonia. Prior to our tenancy, this existing store front has been inactive for many years. 4 5 6 7 Existing entrance at W. 74th Street 7 8 9 10 11 8 Existing Storefront Entrances - Broadway Proposed work . Note: The existing door leaf widths do not meet current ADA handicapped accessibility codes . The existing doors are being replaced in order to meet ADA handicapped accessible door width requirements and current Energy Code requirements.