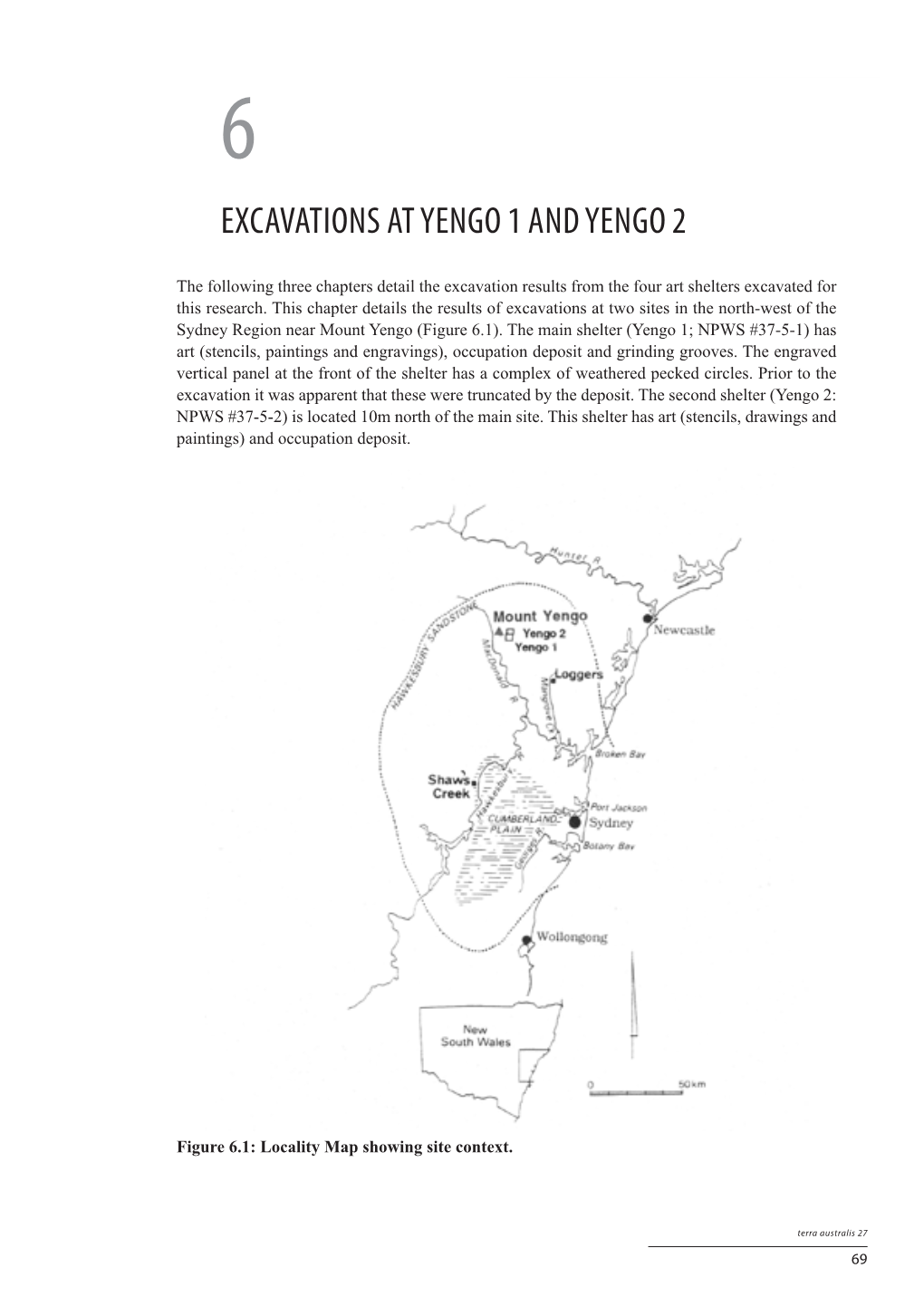

Excavations at Yengo 1 and Yengo 2 6 Excavations at Yengo 1 and Yengo 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area Strategic Plan Addendum 2016

Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area Strategic Plan Addendum 2016 © 2018 State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage With the exception of photographs, the State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) has compiled this report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to their specific needs. All content in this publication is owned by OEH and is protected by Crown Copyright, unless credited otherwise. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), subject to the exemptions contained in the licence. The legal code for the licence is available at Creative Commons. OEH asserts the right to be attributed as author of the original material in the following manner: © State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage 2018. Cover photograph: Kanangra Boyd National Park (Photo: Botanic Gardens Trust/Simone -

The Vertebrate Fauna of Northern Yengo National Park

The Vertebrate Fauna of Northern Yengo National Park Project funded under the Central Branch Parks and Wildlife Division Biodiversity Survey Priorities Program Information and Assessment Section Metropolitan Branch Environmental Protection and Regulation Division Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) June 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project has been undertaken by Helen Hair and Scat Analysis Achurch, Elizabeth Magarey and Daniel Barbara Triggs Connolly from the Metropolitan Branch Information and Assessment, EPRD Bat Call Analysis Section Head, Information and Assessment Narawan Williams Julie Ravallion Special thanks to: Staff of the Hunter Range Area and Central Coordinator, Bioregional Data Group Coast Regional Office for assistance in Daniel Connolly planning and support during the surveys. Private Property owners for allowing us to stay GIS and Database Coordinator on their land and access the park through their Peter Ewin properties. Report Writing and Map Production Daniel Connolly This report should be referenced as follows: Helen Achurch DEC (2005) “The Vertebrate Fauna of Northern Yengo National Park.” Unpublished report Field Surveyors funded by the Central Branch Parks and Narawan Williams Wildlife Division Biodiversity Survey Priorities Martin Schulz Program by NSW Department of Environment Dion Hobcroft and Conservation, Information and Assessment Alex Dudley Section, Metropolitan Branch, Environment Elizabeth Magarey Protection and Regulation Division. Helen Achurch Richard Harris Doug Beckers All photographs are -

New South Wales Topographic Map Catalogue 2008

° 152 153° Y 154° 28° Z AA BB QUEENSLAND 28° Coolangatta SPRING- CURRU- TWEED HEAD WARWICK BROOK MBIN SFingal Head AMG / MGA ZONE 55 AMG /MGA ZONE 56 MT LINDESAY MURWILLUMBAH 9641-4S 9341 Terranora TWEED HEADS KILLAR- WILSON M 9441 LAM- TYAL- S MOUNT OUNT PALEN 9541Tumbulgum Kingscliff 151° NEY PEAK LINDE- COUGAL INGTON GUM MURWILLUMBAH 9641 ° ° CLUNIE CREEK CUDGEN 149 150 KOREELAH N P SAY TYALGUMChillingham9541-2N Condong Bogangar Woodenbong 96 Legume BORDER RANGES 9541-3-N I 41-3N N P Old Hastings Point S EungellaTWEEDI ELBOW VALLEY KOREE TOOLOOM Grevillia MOOBALL NP V LAH I T WOOD MT. WARNING U N P ENBONG Uki Pottsville Beach G W 9341-3-S REVILLIA BRAYS N P 9341-2-S CREEK 9441 BURRINGB I POTTSVIL X -3-S AI R LE 9441-2-S Mount I Grevillia 9541-3S 9541-2 Mooball Goondiwindi Urbenville Lion S 9641-3S TOONUMBAR N P MEBBIN N P MOUNT I MARYLAND Kunghur JERUSALEM N P Wiangaree I N P WYLIE CREEK TOOLOOM NIGHTCAP Ocean Shores GRADULE BOOMI CAPEEN AFTERLE Mullumbimby BOGGABILLA YELARBO 9340-4-N 9340 E NIMBIN N P I 8740-N I N -1-N 9440-4-N HUONBROOK BRUNSWICK 8840-N 9440-1-N I 8940-N 9040-N 9540-4N Nimbin 9540-1NBYRON I Toonumbar I HEA Liston Tooloom GOONENGERRY NP DS I Rivertree Old Bonalbo RICHMOND KYOGLE Cawongla I 9640-4N Kyogle I Boomi I LISTON RANGE N P PADDYS FLATYABBRA BONALBO LISMORERosebank Federal ETTRIC I Byron Bay GO I N P K ONDIWINDI YETMAN 9340-4-S 9340-1-S LARNOOK The D BYRON BAY S R A TEXAS 9440-4-S UNOON BI YRI ON BA STANTHORP Paddys Flat 9440-1-S Cedar 9540 Channon I Y 8940 I E DRAKE -4S 9540-1S Suffolk Park 9040 BON Dryaaba -

Rock Art Thematic Study

Rock Art Thematic Study Jo McDonald and Lucia Clayton 26 May 2016 Report to the Department of the Environment and the Australian Heritage Council Centre for Rock Art Research and Management, University of WA Rock Art Thematic Study Page ii Table of Contents 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Rock art overview ............................................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Introduction to rock art ............................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Regional overview of Australian Aboriginal rock art ..................................................................................... 3 2.2.1 Australian Capital Territory (ACT) ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.2.2 New South Wales ................................................................................................................................................ 7 2.2.3 Northern Territory ............................................................................................................................................. 14 2.2.4 Queensland ...................................................................................................................................................... -

THE GREATER BLUE MOUNTAINS WORLD HERITAGE AREA Your Handy Pocket Sized Guide

THE GREATER BLUE MOUNTAINS WORLD HERITAGE AREA Your Handy Pocket Sized Guide Produced by the Western Sydney Publishing Group western sydney wspublishing.com.au publishing group 2 WHAT A WONDERFUL WORLD The Greater Blue Mountains has been selected by Tourism Australia as providing one of the nation’s top 16 nature experiences. It thus stands in august company, alongside such Australian international tourist icons such as the Great Barrier Reef, Uluru, Kakadu and The Kimberley. Even more significantly it has been selected by the United Nations as a World Heritage Site, having outstanding universal value for mankind. It thus stands along even more august company such as the pyramids of Egypt, the Taj Mahal and the Grand Canyon. Some five million people visit this majestic area each year. It is readily accessible from the nearby Sydney metropolis. This accessibility is a world-wide rarity for a mountainous wilderness area. The visitor can enjoy the landscape and deep forested canyons from a large number of lookouts and an extensive network of well constructed walking tracks. Come and see what makes this area so special. Bruce Leaver, Chair of the GBMWHA Advisory Committee All photos: Ian Brown, NSW NPWS 3 WELCOME TO OUR HERITAGE 4 The Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area sector covers the ground to the south extending to is broken up into four sectors - each with its own the Southern Highlands. distinct set of landscapes, plants and animals and The sector names derive from prominent Aboriginal recreational opportunities to explore. named landscape features to reflect the ongoing To the north, the Mellong and Monundilla sectors Aboriginal association and kinship with the Greater stand alongside each other. -

The Bushwalker Magazine

Volume 31 Issue 1 Summer 2006 Walk Safely—Walk with a Club The Bushwalker ‘Where Am I’ Competition Picture 17 Picture 19 Picture Picture 20 Each Issue has four photos taken You can also see these pictures on the & Travel has donated one $100 voucher somewhere in NSW in places where Confederation web site, along with per issue. bushwalkers go. These will NOT be descriptions and winners. Any financial member of an affiliated obscure places. Bushwalking Club can enter. We may You have to identify the place and Entry requirements check with your Club membership roughly where the photographer was secretary, so make sure you are Just saying something like ‘Blue Gum standing for any ONE of the pictures. financial, so you must include the name Forest’ would not be enough. However, (You do not have to identify all four.) of your club with your entry. something like ‘Blue Gum Forest from Send your answers (up to four per The Editor’s decision is final. After all, he the start of the descent down DuFaurs issue) to the: took the photos. This does mean that Buttress’ would qualify. In short, provide [email protected] some areas of NSW may not appear in enough information that someone else as quickly as possible. the competition for a while. My could navigate to that spot and take a Usually, only one prize per person will apologies to Clubs in those areas. close approximation to the photo. Of be awarded from each issue of The course, if you want to give a map name Bushwalker. -

Ecology of Sydney Plant Species Part 8

Benson & McDougall, Ecology of Sydney plant species 8 241 Ecology of Sydney plant species Part 8 Dicotyledon families Rutaceae to Zygophyllaceae Doug Benson and Lyn McDougall Benson, Doug and McDougall, Lyn (National Herbarium of New South Wales, Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, Australia 2001. Email: [email protected]) 2001 Ecology of Sydney plant species: Part 8 Dicotyledon families Rutaceae to Zygophyllaceae. Cunninghamia 7(2) 241–462. Ecological data in tabular form are provided on 325 plant species of the families Rutaceae to Zygophyllaceae, 236 native and 89 exotics, occurring in the Sydney region, defined by the Central Coast and Central Tablelands botanical subdivisions of New South Wales (approximately bounded by Lake Macquarie, Orange, Crookwell and Nowra). Relevant Local Government Areas are Auburn, Ashfield, Bankstown, Bathurst, Baulkham Hills, Blacktown, Blayney, Blue Mountains, Botany, Burwood, Cabonne, Camden, Campbelltown, Canterbury, Cessnock, Concord, Crookwell, Drummoyne, Evans, Fairfield, Greater Lithgow, Gosford, Hawkesbury, Holroyd, Hornsby, Hunters Hill, Hurstville, Kiama, Kogarah, Ku-Ring-Gai, Lake Macquarie, Lane Cove, Leichhardt, Liverpool, Manly, Marrickville, Mosman, Mulwaree, North Sydney, Oberon, Orange, Parramatta, Penrith, Pittwater, Randwick, Rockdale, Ryde, Rylstone, Shellharbour, Shoalhaven, Singleton, South Sydney, Strathfield, Sutherland, Sydney City, Warringah, Waverley, Willoughby, Wingecarribee, Wollondilly, Wollongong, Woollahra and Wyong. The study area falls within the Sydney Basin IBRA -

Winter Program 2019

Winter Program 2019 THE SYDNEY BUSH WALKERS INC – Winter Program 2019 SYDNEY BUSH WALKERS INC P.O. Box 431 Milsons Point NSW WALKS GRADING Day Walk: A day walk means walking all day - the walks usually start at 8:00am and finish by dark. Often we have dinner afterwards. Weekend Walk: A weekend walk may start Friday night and camp at the start or early Saturday morning. On the first day, the party usually gets to camp after 3:00pm and before dark, (hopefully). Happy hour occurs before dinner and is a time when party members share ‘nibbles’. The next day’s walking could start between first light and 9:00am, usually 8:00 to 8:30am. We usually get back to the cars between early afternoon and dark. After dark finishes do happen, however they are usually not planned for. Often a dinner is arranged at a venue on the way home. THE GRADING SYSTEM The Grading System is shown at the bottom of each page and has 4 categories: (D)istance, (F)itness, (A)scent, (T)errain and (E)xposure Distance S < 10km, M 10-19km, L 20-30km, X >30km; Fitness 1-3; Ascent 1-3; Terrain 1-3; Exposure D - Distance: S - Short under 10 km per day M- Medium 10 - 20 km per day L - Long 20 - 30 km per day X - Extra Long more than 30 km per day F - Fitness: 1 Beginners - frequent long rest breaks 2 Intermediate fitness - stand up regroups, morning tea, lunch and afternoon tea breaks, stops for views 3 Strenuous, fit walkers only - short regroups, short meal breaks A - Ascent: 1 Flat to undulating 2 Undulating with one or more 200m to 300m climbs 3 Climbs of 300m plus, or one or more large steep climbs T - Terrain: 1 Formed tracks and / or open terrain, no scrub 2 Sections of rough track and / or off track and/or creek crossing and / or rock scrambling 3 Similar to 2 for long periods and / or thick scrub E - Exposure: Mild to high exposure to heights (yes or no) Note that some walks may involve an exploratory component where the leader is exploring a new area or feature. -

Assessment of the Yengo Wilderness (PDF

Assessment of the NSW NATIONAL PARKS AND WILDLIFE YYeennggoo SERVICE W I L D E R N E S S Central, Conservation Programs and Planning Division NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service November 2001 ASSESSMENT OF THE YENGO WILDERNESS Central Conservation Programs & Planning Division NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service November 2001 ASSESSMENT OF THE YENGO WILDERNESS CONTENTS List of Tables ................................................................................................... 3 List of Figures.................................................................................................. 3 Abbreviations appearing in report ................................................................. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................5 1 Introduction................................................................................................ 8 2 Definition and History of Wilderness ..................................................... 10 2.1 Concept of Wilderness.............................................................................. 10 2.2 History of Wilderness................................................................................ 12 2.3 Definitions of Wilderness .......................................................................... 14 3 Identification of Wilderness.................................................................... 16 3.1 Criteria under National Wilderness Inventory............................................ 16 3.2 Criteria under Wilderness -

VEGETATION, FIRE and CLIMATE CHANGE in the GREATER BLUE MOUNTAINS WORLD HERITAGE AREA

VEGETATION, FIRE AND CLIMATE CHANGE in the GREATER BLUE MOUNTAINS WORLD HERITAGE AREA Kate Hammill and Liz Tasker VEGETATION, FIRE AND CLIMATE CHANGE in the GREATER BLUE MOUNTAINS WORLD HERITAGE AREA Kate Hammill and Liz Tasker An Environmental Trust funded project 2 VEGETATION, FIRE AND CLIMATE CHANGE in the GREATER BLUE MOUNTAINS WORLD HERITAGE AREA Kate Hammill and Liz Tasker 3 Acknowledgements This publication was funded by a dissemination grant from the NSW Environmental Trust. It follows a three-year research project, also funded by the Environmental Trust, Biodiversity re- sponses to fire regimes under climate change (2004/RD/0104). The findings from the research project form part of the content of this booklet. Most of the maps in this publication were com- pleted as part of a project funded by the Australian Government Caring for our Country, World Heritage Property Management Program (2008–09), which is summarised in Hammill, Tasker, & Reid (2010) Monitoring Fire Regimes and Biodiversity in the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, an unpublished Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW (DECCW) report to the Australian Government Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts and Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. The fire history maps were compiled from extensive records and digital layers kept by the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service (now part of DECCW). The vegetation map made use of extensive and detailed local vegetation maps prepared by the Information and Assessment Section, Metropolitan Branch of DECCW (see Further Reading for details). We also acknowledge the prior work of Saskia Hayes in collating some of the vegetation maps for the World Heritage Area. -

Sydney Basin Rock Art and Prehistoric Information Exchange / Jo Mcdonald

terra australis 27 © 2008 ANU E Press Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: McDonald, Josephine. Title: Dreamtime superhighway : an analysis of Sydney Basin rock art and prehistoric information exchange / Jo McDonald. ISBN: 9781921536168 (pbk.) 9781921536175 (pdf) Series: Terra Australis ; 27 Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Rock paintings--New South Wales--Sydney Basin. Petroglyphs--New South Wales--Sydney Basin. Visual communication in art--New South Wales--Sydney Basin. Art, Aboriginal Australian--New South Wales--Sydney Basin. Aboriginal Australians--New South Wales--Sydney Basin--Antiquities. Dewey Number: 709.011309944 Copyright of the text remains with the contributors/authors, 2006. This book is copyright in all countries subscribing to the Berne convention. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Series Editor: Sue O’Connor Typesetting and design: Silvano Jung Cover photograph by Jo McDonalnd Back cover map: Hollandia Nova. Thevenot 1663 by courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Reprinted with permission of the National Library of Australia. Terra Australis Editorial Board: Sue O’Connor, Jack Golson, Simon Haberle, Sally Brockwell, Geoffrey Clark Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. -

History at St Clair

‘We want to do what they did’: History at St Clair Rosa Nolan 9/10/2012 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a BA (hons.) University of Sydney Department of History. ‘The history in places, especially in places of cross-cultural encounters, will take as much imagination as science to see. Blood and ashes are blown away with the dust. Shouts and songs die in the wind. Pain and happiness are as evanescent as memory. To catch lost passions in places history will have to be a little more artful than being a “non-fiction”. It will have to have, among other graces, a trust in and a sense of the continuities of living through different times, despite all the transformations and translations that masquerade as discontinuity.’ Dening, Greg. "The History in Things and Places." In Prehistory to Politics: John Mulvaney, the Humanities and the Public Intellectual, edited by Tim Bonyhady and Tom Griffiths. 85-97. South Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1996. p.97. The Front Cover image is of Luke Hickey, Arthur Fletcher, NSW Minister for Environment and Heritage Robyn Parker, Laurie Perry, Maxine Conaty, Tracy Skene and John Lester at the opening of the Wonnarua Nation Aboriginal Corporation’s Biobanking project at Valley Arms, holding their possum skin cloak. It was taken from the biobanking webpage of the WNAC’s website. 2 Abstract In 1999 the Wonnarua Nation Aboriginal Corporation acquired the site of the former St Clair Mission where their forebears lived. They will recreate to turn it into a cultural centre that will sustain and strengthen their community and they are pursuing reclamation and recreation of language, material culture, art, family and public history projects.