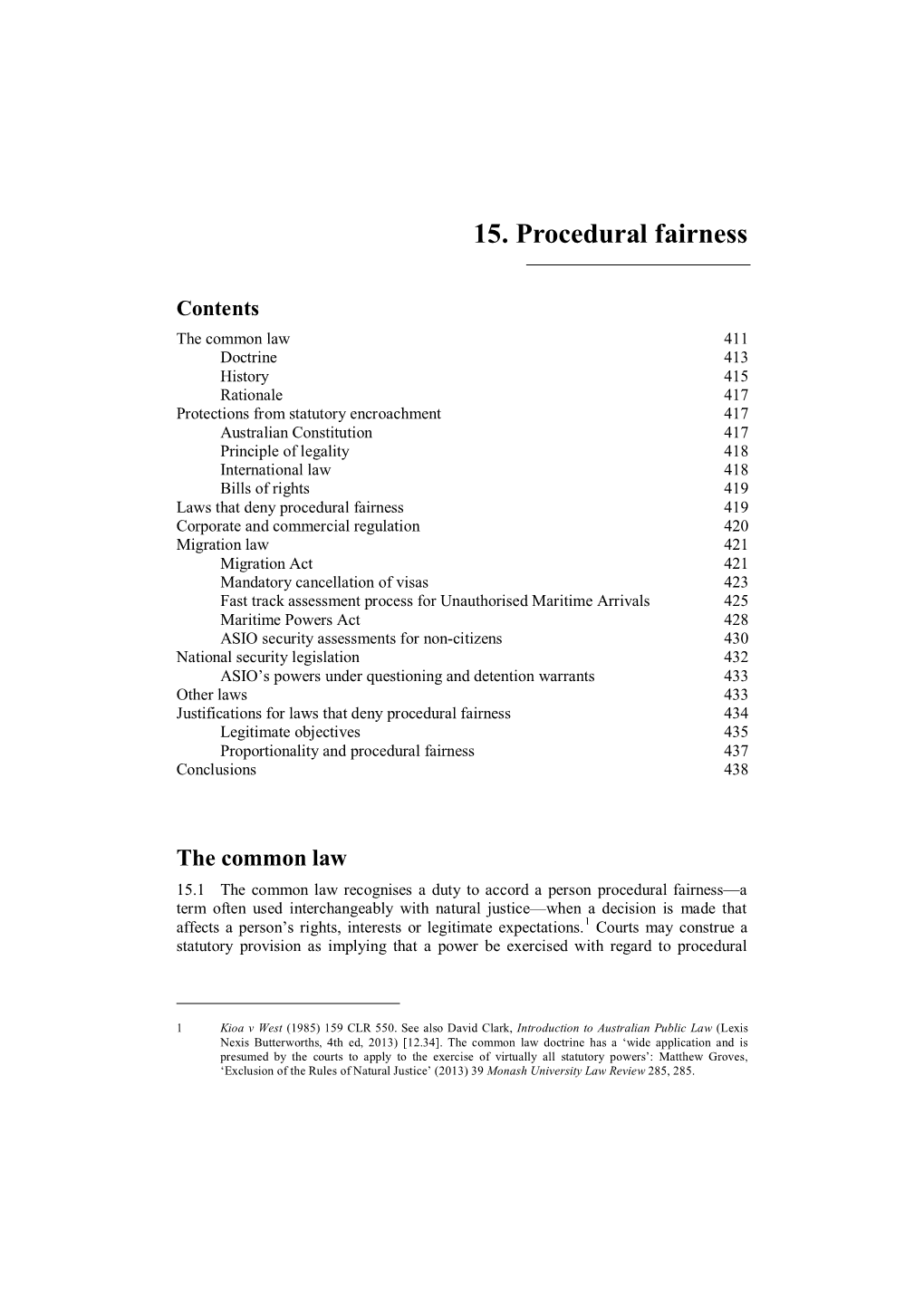

15. Procedural Fairness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Substantive Equality As a Principle of Fundamental Justice

411 Constitutional Coalescence: Substantive Equality as a Principle of Fundamental Justice KERRI A. FROC* In this article, the author posits that the principles of Dans cet article, I'auteure soutient que les principes fundamental justice present tantalizing possibilities de justice fondamentale pr6sentent des possibilit6s in the quest to use constitutional law to ameliorate tentantes dans le cadre de la quote visant ase servir the real conditions of disadvantage and subordination du droit constitutionnel pour am6liorer la condition faced by women. As a way out of the stultified sociale de d6savantage et de subordination des femmes. comparative analysis in equality cases and a sec- A titre de solution pour s'6carter de I'analyse com- tion 7 analysis that has often been impervious to parke, figbe, des causes en matibre d'6galit6 Ct d'une gendered relations of domination, she proposes a analyse de I'article 7 souvent imperm6able aux rela- new use for the right to substantive equality repre- tions de domination fond6es sur lc genre, elle pro- sented in section 15(1) of the Canadian Charter of pose un nouvel usage pour Ic droit i l'galit& rclile Rights and Freedoms: as a principle of fundamental garanti par le paragraphe 15(1) de la Charte canadienne justice. Using the examples of the 1988 decision des droits et libertis : soit en tant que principe de justice in R v Morgentaler, 119881 I SCR 30 and subsequent fondamentale. A I'aide d'exemples comme la d6ci- abortion litigation and proposed legislation as a case sion de 1988 dans I'affaire R c Morgentaler, 119881 1 study, she addresses the questions of the difference it RCS 30, les litiges subs6quents concernant la ques- would make to have substantive equality recognized tion de l'avortement ct les projets de lois aff6rents as a principle of fundamental justice in granting women prises comme 6tudes de cas, elleexplore Ia diff6rence equal access to Charter rights. -

The Justice of Administration: Judicial Responses to Excute Claims of Independent Authority to Intrepret the Constitution

Florida State University Law Review Volume 33 Issue 1 Article 4 2005 The Justice of Administration: Judicial Responses to Excute Claims of Independent Authority to Intrepret the Constitution Brian Galle [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian Galle, The Justice of Administration: Judicial Responses to Excute Claims of Independent Authority to Intrepret the Constitution, 33 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. (2005) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol33/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW THE JUSTICE OF ADMINISTRATION: JUDICIAL RESPONSES TO EXCUTE CLAIMS OF INDEPENDENT AUTHORITY TO INTREPRET THE CONSTITUTION Brian Galle VOLUME 33 FALL 2005 NUMBER 1 Recommended citation: Brian Galle, The Justice of Administration: Judicial Responses to Excute Claims of Independent Authority to Intrepret the Constitution, 33 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 157 (2005). THE JUSTICE OF ADMINISTRATION: JUDICIAL RESPONSES TO EXECUTIVE CLAIMS OF INDEPENDENT AUTHORITY TO INTERPRET THE CONSTITUTION BRIAN GALLE* I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................. 157 II. SOME BACKGROUND ON THE BACKGROUND RULES ........................................... 164 III. -

The Right to Reasons in Administrative Law H.L

1986] RIGHT TO REASONS 305 THE RIGHT TO REASONS IN ADMINISTRATIVE LAW H.L. KUSHNER* It is generally accepted that there is no common Jaw right to reasons in administrative Jaw. The author reviews the Jaw to determine whether such a right exists and whether it has been changed by the enactment of the Charter of Rights. He questions whether a statutory obligation to give reasons should be enacted. FinaJJy,he looks at the effect of failing to comply with such a requirement. He concludes that although the rules of natural justice and the enactment of s. 7 of the Charter of Rights would support a right to reasons, the courts are reluctant to impose such an obligation on the administrative decision-makers. He feels that the legislatures should require reasons. An ad ministrative decision should be ineffective without reasons if such a requirement were imposed either by the courts or the legislatures. "It may well be argued that there is a third principle of natural justice, 1 namely, that a party is entitled to know the reason for the decision, be it judicial or quasi-judicial". 2 As early as 1875 it is possible to find case authority to support the proposition that if not reasons, at least the grounds upon which a decision has been made must be stated. 3 Certainly there is an abundant number of governmental reports and studies, 4 as well as academic writings 5 which support the value of reasons. However, the majority of these adopt the view that a requirement for reasons does oc. -

The Principles of Fundamental Justice, Societal Interests and Section I of the Charter

THE PRINCIPLES OF FUNDAMENTAL JUSTICE, SOCIETAL INTERESTS AND SECTION I OF THE CHARTER Thomas J. Singleton* Halifax In this article, the authordiscusses the approach ofthe Supreme Court ofCanada to the treatment ofsocietal interests in cases involving section 7 ofthe Charter. From a review of the cases where the Court has considered the issue of where to balance societal interests - in the determination of whether there has been a violation ofthe principles offundamentaljustice or in the analysis under section 1 - it becomes apparent that the Court is far from having any conceptually coherent approach to this issue, which is often determinative ofindividual rights under section 7. The author demonstrates that there are, in fact, two radically different approaches to the treatment of societal interests in section 7 cases, resulting in a situation where the lower courts and the profession at large are effectively without directionfrom the Court on this extremely important issue. The author argues that the tendency ofsomejustices to import societal interests into the determination ofthe principles offundamentaljustice effectively emasculates the rights guaranteedby section 7because the resulting additional burden ofproof on the individual rights claimant is excessively onerous. Dans cet article, l'auteur discute du traitement qu'accorde la Cour suprême du Canada aux intérêts de la société dans les causes impliquant l'article 7 de la Charte. L'auteurpasse en revue les arrêts où la Cour a considéré la question de savoiroù les intérêts de la société devaient êtrepris en compte - en déterminant s'il .y a eu ou non violation des principes de la justice fondamentale ou dans l'analyse aux termes de l'article 1. -

The Constitution and Administrative Law – Unfulled Promises

The Charter in Administrative Law: Unfulfilled Promises and Future Prospects David Stratas∗ The unfulfilled promise of s. 7 of the Charter When the Charter first became part of our law, many administrative law practitioners were optimistic that s. 7 of the Charter might have wide application in Charter proceedings. However, this promise has not been fulfilled. The limited scope of the rights to liberty and security of the person Administrative tribunals and civil courts are subject to obligations to afford procedural fairness at common law but those obligations can be ousted by clear statutory wording. Can the Charter limit such statutes and guarantee procedural fairness? The answer to that question depended on how the Court interprets s. 7 of the Charter. Section 7 is the one right under the Charter that theoretically speaks to the issue of procedural fairness. Section 7 guarantees the application of the principles of fundamental justice to those whose rights to liberty and security of the person are infringed. The principles of fundamental justice seem susceptible to an interpretation that would include procedural fairness. Obviously, the broader the interpretation of the rights to liberty and security of the person, the broader the scope of constitutional protection for procedural fairness. A bold court in the area of procedural matters would be inclined to give the rights to liberty and security of the person a broad interpretation to ensure that the standards of "fundamental justice" have a broad application. However, the rights to liberty and security of the person have been given a fairly narrow interpretation. Perhaps the best way to illustrate this is a close examination of the recent administrative law case of Blencoe v. -

Petitioner, V

NO. 20-______ In the Supreme Court of the United States ________________ JUSTIN MICHAEL WOLFE, Petitioner, v. COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, Respondent. ________________ On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Virginia ________________ PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI ________________ MARVIN D. MILLER ASHLEY C. PARRISH THE LAW OFFICES OF Counsel of Record MARVIN D. MILLER JILL R. CARVALHO 1203 Duke Street KING & SPALDING LLP Alexandria, VA 22314 1700 Pennsylvania Ave. NW (703) 548-5000 Washington, DC 20006 [email protected] (202) 737-0500 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Petitioner January 29, 2021 QUESTION PRESENTED After petitioner Justin Wolfe obtained federal habeas relief because of “abhorrent” prosecutorial misconduct, the Commonwealth of Virginia vindictively brought six new charges with more severe penalties against Wolfe. Instead of requiring the Commonwealth to justify the new charges, the trial court rejected the vindictive prosecution claim on grounds that are manifestly wrong. With no chance of a fair trial, Wolfe entered a plea and then, on appeal, argued that the trial court had no authority to convict or sentence him because of the vindictive prosecution. Instead of addressing the federal constitutional issues raised by that claim, the Virginia courts concluded that Wolfe’s guilty plea waived his right to appeal. This Court granted certiorari, vacated the judgment, and directed the Virginia courts to consider Class v. United States, 138 S. Ct. 798 (2018). On remand, the Virginia courts recognized that Wolfe’s guilty plea does not bar his appeal. But they invented another reason not to address Wolfe’s vindictive prosecution claim, holding that Wolfe forfeited his appellate rights because he purportedly did not preserve an argument in favor of his position. -

On the Connection Between Law and Justice Anthony D'amato Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected]

Northwestern University School of Law Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Working Papers 2011 On the Connection Between Law and Justice Anthony D'Amato Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected] Repository Citation D'Amato, Anthony, "On the Connection Between Law and Justice" (2011). Faculty Working Papers. Paper 2. http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/facultyworkingpapers/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. On the Connection Between Law and Justice, by Anthony D'Amato,* 26 U. C. Davis L. Rev. 527-582 (1992-93) Abstract: What does it mean to assert that judges should decide cases according to justice and not according to the law? Is there something incoherent in the question itself? That question will serve as our springboard in examining what is—or should be—the connection between justice and law. Legal and political theorists since the time of Plato have wrestled with the problem of whether justice is part of law or is simply a moral judgment about law. Nearly every writer on the subject has either concluded that justice is only a judgment about law or has offered no reason to support a conclusion that justice is somehow part of law. This Essay attempts to reason toward such a conclusion, arguing that justice is an inherent component of the law and not separate or distinct from it. -

Habeas Corpus Law for Prison Administrators

Habeas Corpus Law for Prison Administrators 2018 CanLIIDocs 246 Gerard Mitchell Case comment: Mission Institute v. Khela, [2014] 1 S.C.R. 502 2018 CanLIIDocs 246 [1] Habeas Corpus proceedings are the way in which prisoners can challenge the lawfulness of their confinement. [2] In the last few years federal penitentiary administrators have found themselves spending a lot of time and resources defending their decisions in habeas corpus proceedings before provincial superior courts. [3] The trend is likely to continue because the March 27, 2014 decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in the case of Mission Institute v. Khela, [2014] 1 S.C.R. 502 strongly supports a broad scope for habeas corpus review by affirming that provincial courts can assess both the procedural fairness and the reasonableness of a decision in order to determine if an individual’s detention is lawful. 2018 CanLIIDocs 246 [4] The Court also ruled that correctional authorities have significant disclosure obligations in an involuntary transfer context, and that information can only be withheld when the commissioner of Corrections or his or her representative has reasonable grounds to believe that should the information be released it might threaten the security of the prison, the safety of any person, or interfere with the conduct of an investigation. [5] Section 10(c) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees everyone detained the right to have the validity of their detention determined by way of habeas corpus and to be released if the detention is not lawful. Everyone includes prisoners. [6] Prisoners have a Charter right not to be deprived of their residual liberties except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice (s.7) and they have a Charter right not to be arbitrarily detained (s.9). -

Reassessing the Constitutional Foundation of Delegated Legislation in Canada

Dalhousie Law Journal Volume 41 Issue 2 Article 8 10-1-2018 Reassessing the Constitutional Foundation of Delegated Legislation in Canada Lorne Neudorf University of Adelaide Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/dlj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Lorne Neudorf, "Reassessing the Constitutional Foundation of Delegated Legislation in Canada" (2018) 41:2 Dal LJ 519. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Schulich Law Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dalhousie Law Journal by an authorized editor of Schulich Law Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lorne Neudorf* Reassessing the Constitutional Foundation of Delegated Legislation in Canada This article assesses the constitutional foundation by which Parliament lends its lawmaking powers to the executive, which rests upon a century-old precedent established by the Supreme Court of Canada in a constitutional challenge to wartime legislation. While the case law demonstrates that courts have continued to follow this early precedent to allow the parliamentary delegation of sweeping lawmaking powers to the executive, it is time for courts to reassess the constitutionality of delegation in light of Canada's status as a liberal democracy embedded within a system of constitutional supremacy. Under the Constitution of Canada, Parliament is placed firmly at the centre of public policymaking by being vested with exclusive legislative authority in certain subject matters. Parliament must therefore play the principal federal lawmaking role. The Supreme Court's 1918 judgment should no longer be followed to the extent that it allows courts to accept near unlimited delegation of Parliament's lawmaking powers to the executive. -

![Suresh V. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), [2002] 1 S.C.R](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3589/suresh-v-canada-minister-of-citizenship-and-immigration-2002-1-s-c-r-2413589.webp)

Suresh V. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), [2002] 1 S.C.R

Suresh v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), [2002] 1 S.C.R. 3, 2002 SCC 1 Manickavasagam Suresh Appellant v. The Minister of Citizenship and Immigration and the Attorney General of Canada Respondents and The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Amnesty International, the Canadian Arab Federation, the Canadian Council for Refugees, the Federation of Associations of Canadian Tamils, the Centre for Constitutional Rights, the Canadian Bar Association and the Canadian Council of Churches Interveners Indexed as: Suresh v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) Neutral citation: 2002 SCC 1. File No.: 27790. 2001: May 22; 2002: January 11. Present: McLachlin C.J. and L’Heureux-Dubé, Gonthier, Iacobucci, Major, Bastarache, Binnie, Arbour and LeBel JJ. on appeal from the federal court of appeal - 2 - Constitutional law — Charter of Rights — Fundamental justice — Immigration — Deportation — Risk of torture — Whether deportation of refugee facing risk of torture contrary to principles of fundamental justice — Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s. 7 — Immigration Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. I-2, s. 53(1)(b). Constitutional law — Charter of Rights — Fundamental justice — Vagueness — Whether terms “danger to the security of Canada” and “terrorism” in deportation provisions of immigration legislation unconstitutionally vague — Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s. 7 — Immigration Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. I-2, ss. 19(1), 53(1)(b). Constitutional law — Charter of Rights — Freedom of expression — Freedom of association — Whether deportation for membership in terrorist organization infringes freedom of association and freedom of expression — Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, ss. 2(b), 2(d) — Immigration Act, R.S.C. -

Fundamental Justice and the Deflection of Refugees from Canada

Osgoode Hall Law Journal Volume 34 Issue 2 Volume 34, Number 2 (Summer 1996) Article 1 4-1-1996 Fundamental Justice and the Deflection of Refugees from Canada James C. Hathaway R. Alexander Neve Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj Part of the Immigration Law Commons Article This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Hathaway, James C. and Neve, R. Alexander. "Fundamental Justice and the Deflection of Refugees from Canada." Osgoode Hall Law Journal 34.2 (1996) : 213-270. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol34/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Osgoode Hall Law Journal by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Fundamental Justice and the Deflection of Refugees from Canada Abstract Canada is preparing to implement a controversial provision of the Immigration Act that will deny asylum seekers the opportunity even to argue their need for protection from persecution. Under a policy labelled "deflection" by the authors, the claims of refugees who travel to Canada through countries deemed safe, likely the United States and eventually Europe, will be rejected without any hearing on the merits. Because deflection does not equirr e substantive or procedural harmonization of refugee law among partner states, it will severely compromise the ability of genuine refugees to seek protection. The article considers the impact of the Singh ruling of the Supreme Court of Canada and subsequent jurisprudence to determine whether a deflection system can be econciledr to the requirements of sections 7 and 1 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. -

Unenumerated Rights

COMPARATIVE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW (U.S./CANADA/AUSTRALIA),2009 ed. 2‐1 CHAPTER TWO: UNENUMERATED RIGHTS KEY CONCEPTS FOR THE CHAPTER ● U.S. COURTS HAVE HELD THAT THE FIFTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS’ PROTECTION AGAINST DEPRIVATION OF LIBERTY WITHOUT DUE PROCESS OF LAW HAS TWO COMPONENTS: LIBERTY CANNOT BE DEPRIVED UNLESS CERTAIN PROCEDURES ARE USED BY GOVERNMENT, AND CERTAIN RIGHTS THAT ARE ENCOMPASSED BY “LIBERTY” CANNOT BE DEPRIVED UNLESS THE GOVERNMENT CAN JUSTIFY THE DEPRIVATION. THE LATTER CONCEPT IS KNOWN AS “SUBSTANTIVE DUE PROCESS” ● IN NEITHER CANADA NOR THE U.S. ARE INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS ABSOLUTE. ‐ IN THE U.S., CERTAIN “FUNDAMENTAL” RIGHTS CAN BE LIMITED ONLY IF THE GOVERNMENT PERSUADES JUDGES THAT THERE ARE GOOD REASONS FOR DOING SO; FOR “NON‐FUNDAMENTAL” RIGHTS, COURTS DEFER TO LEGISLATIVE JUDGMENTS UNDER THE SO‐CALLED “RATIONAL BASIS” TEST ‐ IN CANADA, THE CHARTER PROTECTS “FUNDAMENTAL” RIGHTS AND SUBJECTS THEM TO CLOSE SCRUTINY UNDER A 4‐PRONG TEST (THE “OAKES” TEST); NON‐FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS ARE SIMPLY DEEMED NOT TO BE PROTECTED BY THE CHARTER ● GIVEN THE BREADTH OF THE LANGUAGE OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT AND S.7 OF THE CANADIAN CHARTER, IDENTIFICATION OF RIGHTS WORTHY OF ACTIVE JUDICIAL PROTECTION IS A MATTER OF JUDICIAL DISCRETION AND JUDGMENT, CONSIDERING THE TEXT, HISTORY, PRECEDENTS, AND ABILITY OF COURTS TO APPLY JUDICIALLY MANAGEABLE STANDARDS ‐ IN PARTICULAR, JUDGES ON BOTH SIDES OF THE BORDER STRUGGLE TO DISTINGUISH THE PROTECTION OF RIGHTS FROM THE DISCREDITED “LOCHNER ERA,” WHICH HISTORY SUGGESTS INVOLVED JUDGES STRIKING DOWN PROGRESSIVE LEGISLATION BECAUSE OF THEIR PERSONAL RIGHT‐WING POLITICAL VIEWS • THE AUSTRALIAN FRAMERS INCORPORATED SEVERAL RIGHTS INTO THE CONSTITUTION, BUT EXPLICITLY REJECTED OPEN‐ENDED CONSTITUTIONAL ENTRENCHMENT OR INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS.