Donors Do Not Trust Actor-Networks and Intermedia Agenda-Setting in Online Climate News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S5011

July 12, 2016 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S5011 The clerk will report the bill by title. COMMENDING THE TENNESSEE experienced its warmest June on record The senior assistant legislative clerk VALLEY AUTHORITY ON THE ever. Already this year there have been read as follows: 80TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE UNI- eight weather-related and climate-re- A bill (S. 2650) to amend the Internal Rev- FIED DEVELOPMENT OF THE lated disasters that each caused at enue Code of 1986 to exclude from gross in- TENNESSEE RIVER SYSTEM least $1 billion in damage. Globally, it come any prizes or awards won in competi- Mr. COTTON. Mr. President, I ask was found that 2015 was the hottest tion in the Olympic Games or the year on record, and so far this year is Paralympic Games. unanimous consent that the Senate proceed to the consideration of S. Res. on track to beat last year. We can’t There being no objection, the Senate 528, submitted earlier today. even hold the record for a year—2016 proceeded to consider the bill. The PRESIDING OFFICER. The has been as hot as Pokemon GO—and Mr. COTTON. Mr. President, I ask clerk will report the resolution by anyone watching the Senate floor to- unanimous consent that the bill be title. night who is younger than 31 has never read a third time and passed, the mo- The senior assistant legislative clerk experienced in their life a month where tion to reconsider be considered made read as follows: the temperature was below the 20th and laid upon the table, and that the century average. -

Theda Skocpol

NAMING THE PROBLEM What It Will Take to Counter Extremism and Engage Americans in the Fight against Global Warming Theda Skocpol Harvard University January 2013 Prepared for the Symposium on THE POLITICS OF AMERICA’S FIGHT AGAINST GLOBAL WARMING Co-sponsored by the Columbia School of Journalism and the Scholars Strategy Network February 14, 2013, 4-6 pm Tsai Auditorium, Harvard University CONTENTS Making Sense of the Cap and Trade Failure Beyond Easy Answers Did the Economic Downturn Do It? Did Obama Fail to Lead? An Anatomy of Two Reform Campaigns A Regulated Market Approach to Health Reform Harnessing Market Forces to Mitigate Global Warming New Investments in Coalition-Building and Political Capabilities HCAN on the Left Edge of the Possible Climate Reformers Invest in Insider Bargains and Media Ads Outflanked by Extremists The Roots of GOP Opposition Climate Change Denial The Pivotal Battle for Public Opinion in 2006 and 2007 The Tea Party Seals the Deal ii What Can Be Learned? Environmentalists Diagnose the Causes of Death Where Should Philanthropic Money Go? The Politics Next Time Yearning for an Easy Way New Kinds of Insider Deals? Are Market Forces Enough? What Kind of Politics? Using Policy Goals to Build a Broader Coalition The Challenge Named iii “I can’t work on a problem if I cannot name it.” The complaint was registered gently, almost as a musing after-thought at the end of a June 2012 interview I conducted by telephone with one of the nation’s prominent environmental leaders. My interlocutor had played a major role in efforts to get Congress to pass “cap and trade” legislation during 2009 and 2010. -

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: the Unmaking of America: a Recent History

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History Introduction xiv “If infectious greed is the virus” Kurt Andersen, “City of Schemes,” The New York Times, Oct. 6, 2002. xvi “run of pedal-to-the-medal hypercapitalism” Kurt Andersen, “American Roulette,” New York, December 22, 2006. xx “People of the same trade” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, ed. Andrew Skinner, 1776 (London: Penguin, 1999) Book I, Chapter X. Chapter 1 4 “The discovery of America offered” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy In America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2012), Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “A new science of politics” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “The inhabitants of the United States” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Chapter XVIII. 5 “there was virtually no economic growth” Robert J Gordon. “Is US economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the six headwinds.” Policy Insight No. 63. Centre for Economic Policy Research, September, 2012. --Thomas Piketty, “World Growth from the Antiquity (growth rate per period),” Quandl. 6 each citizen’s share of the economy Richard H. Steckel, “A History of the Standard of Living in the United States,” in EH.net (Economic History Association, 2020). --Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016), p. 98. 6 “Constant revolutionizing of production” Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969), Chapter I. 7 from the early 1840s to 1860 Tomas Nonnenmacher, “History of the U.S. -

Accelerated Attacks on Clean Energy by Koch Bros

Checks and Balances Project Documents: Accelerated Attacks on Clean Energy by Koch Bros. $192 Million to 72 Groups Associated with Opposition to Clean Energy Solutions and Climate Change Denial from 1997-2013 $108 Million to At Least 19 Groups to Fight State Renewable Energy Policies 2011-2013 (Over 18 months, Checks and Balances Project conducted the first in-depth investigation into Koch Industries, Inc. AND what we call the Koch Advocacy Network. Over 350 low-profile regulatory disclosures and more than 8,000 legal disclosure forms drawn from over 60 public agencies, databases and courts were examined. Research was completed prior to the 2016 election.) In August 2015 President Obama singled out the “massive lobbying efforts backed by fossil fuel interests, or conservative think tanks, or the Koch brothers pushing for new laws to roll back renewable energy standards or prevent new clean energy businesses from succeeding.” The President described these anti-clean energy efforts as “rent seeking and trying to protect old ways of doing business and standing in the way of the future.”1 Charles Koch responded that, “We are not trying to prevent new clean energy businesses from succeeding” and warned against “subsidizing uneconomical forms of energy — whether you call them ‘green,’ ‘renewable’ or whatever.” He continued, “And there is a big debate on whether you have a real disease or something that’s not that serious. I recognize there is a big debate about that. But whatever it is, the cure is to do things in the marketplace, and to let individuals and companies innovate, to come up with alternatives that will deal with whatever the problem may be in an economical way so we don’t squander resources on uneconomic approaches.” 2 The defense outlined by Charles mirrors the strategy of the network he oversees. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Robert J. Brulle Professor of Sociology and Environmental Science Department of Culture and Communications Drexel University 3141 Chestnut Street Philadelphia, PA. 19104 Phone: 215 895 2294 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. George Washington University, Sociology M.S. University of Michigan, Natural Resources M.A. New School for Social Research, Sociology B.S. United States Coast Guard Academy, Marine Engineering PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2013-2014 Invited guest participant - 2013-14 Theme Seminar - “Environmental Turn and the Human Sciences” Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton University 2012 - 2013 Fellow, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University 2008 – Present Professor of Sociology & Environmental Science and Affiliate Professor of Public Health, Drexel University 2003 to 2008 Associate Professor of Sociology & Environmental Science and Affiliate Associate Professor of Public Health, Drexel University 1997 to 2003 Assistant Professor of Sociology & Environmental Science, Drexel University 1996 Summer Visiting Professor, Sociology Department, Johann Wolfgang Goethe- Universität, Frankfurt, Germany 1996 Spring Visiting Professor, Sociology Department, University of Uppsala, Sweden 1995 to 1996 Research Associate and Lecturer, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA 1974 to 1994 Commissioned Officer, United States Coast Guard SCHOLARSHIP Books Dunlap, Riley, and Brulle, Robert J., (eds.) Forthcoming. Sociological Perspectives on Climate Change. Oxford Press: New York: NY Pellow, -

Koch Millions Spread Influence Through Nonprofits, Colleges

HOME ABOUT STAFF INVESTIGATIONS ILAB BLOGS WORKSHOP NEWS Koch millions spread influence through nonprofits, colleges B Y C H A R L E S L E W I S , E R I C H O L M B E R G , A L E X I A F E R N A N D E Z C A M P B E L L , LY D I A B E Y O U D Monday, July 1st, 2013 ShareThis Koch Industries, one of the largest privately held corporations in the world and principally owned by billionaires Charles and David Koch, has developed what may be the best funded, multifaceted, public policy, political and educational presence in the nation today. From direct political influence and robust lobbying to nonprofit policy research and advocacy, and even increasingly in academia and the broader public “marketplace of ideas,” this extensive, cross-sector Koch club or network appears to be unprecedented in size, scope and funding. And the relationship between these for-profit and nonprofit entities is often mutually reinforcing to the direct financial and political interests of the behemoth corporation — broadly characterized as deregulation, limited government and free markets. The cumulative cost to Koch Industries and Charles and David Koch for this extraordinary alchemy of political and lobbying influence, nonprofit public policy underwriting and educational institutional support was $134 million over a recent five- year period. The global conglomerate has 60,000 employees and annual revenue of $115 billion and estimated pretax profit margins of 10 percent, according to Forbes. An analysis by the Investigative Reporting Workshop found that from 2007 through 2011, Koch private foundations gave $41.2 million to 89 nonprofit organizations and an annual libertarian conference. -

Monetized Hate: Decoding the Network

MONETIZED HATE: DECODING THE NETWORK THE NETWORK REVISITED The present scourge of anti-Arab and anti-Muslim bigotry in our country is rooted in a calculated, insidious effort to contaminate our public discourse. This effort dates back to the early 2000s, when a small, interlaced network of analysts and activists exploited a nationwide climate of fear in the aftermath of 9/11. To be sure, the systemic mistreatment of our Arab American and American Muslim communities did not begin with the new millennium. However, the success of this so-called network to mainstream hateful rhetoric and advance discriminatory policies is considerable, and thus deserves outsize attention. In 2011, The Center for American Progress (CAP) published “Fear, Inc. The Roots of the Islamophobia Network in America.”1 The report found that a nationwide rise in anti-Muslim bigotry was traceable to a handful of “misinformation experts.” These individuals and their organizations relied on a syndicate of activists, media partners, and grassroots organizing to radiate bias presented as fact. They also relied on significant financial support from a select group of charitable foundations. This network of donors, analysts, and activists not only distorted millions of Americans’ understanding of Islam and Muslims, it also drove inequitable policies. One example highlighted in the report was that of so-called “anti-Sharia bills”2 introduced in numerous state legislatures. Most of these bills drew from model legislation drafted by David Yerushalmi,3 an SPLC-designated anti-Muslim extremist. CAP released a follow-up in 2015 entitled “Fear Inc., 2.0. The Islamophobia Network’s Effects to Manufactured Hate in America.” 4 While the revelations of CAP’s initial report led charitable organizations, politicians, and the media to sever ties with many of the network’s key members, the 2015 edition also found that individuals within the network had successfully advanced a range of anti-Muslim policies at the local, state, and federal level. -

Protecting Donor Privacy Philanthropic Freedom, Anonymity and the First Amendment

Protecting Donor Privacy Philanthropic Freedom, Anonymity and the First Amendment www.PhilanthropyRoundtable.org www.ACReform.org Contents 1 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 3 A Rich Tradition and History of Anonymous Giving 7 A Constitutionally Protected Right 9 Activists and Attorneys General Threaten Donor Privacy 13 Legislators Seek to Undermine Anonymous Giving 14 Is Anonymity Still Needed? 16 Confusing Politics, Government, and Charity 18 Ideology and Donor Privacy 20 Donor Anonymity is Worth Protecting 22 Endnotes Executive Summary among them for supporters of unpopular causes or organizations is the reality that exposure will lead to harassment or threat The right of charitable donors to remain of retribution. anonymous has long been a hallmark of American philanthropy for donors both large Among the more prominent examples is the and small. Donor privacy allows charitable harassment of brothers Charles and David givers to follow their religious teachings, Koch, who have helped fund a broad range insulate themselves from retribution, avoid of nonprofit organizations ranging from unwanted solicitations, and duck unwelcome Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center publicity. It also upholds and protects important to the libertarian-oriented Cato Institute, as First Amendment rights of free speech and well as organizations that engage in political association. However, recent actions by activity. As a result of their giving, the Koch elected officials, activists, and organizations brothers and their companies routinely face are challenging this right and threatening death threats, cyber-attacks from the hacker to undermine private philanthropy’s ability group “Anonymous,” and boycotts aimed at to effectively address some of society’s most the many consumer products their companies challenging issues. -

Threat from the Right Intensifies

THREAT FROM THE RIGHT INTENSIFIES May 2018 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................1 Meeting the Privatization Players ..............................................................................3 Education Privatization Players .....................................................................................................7 Massachusetts Parents United ...................................................................................................11 Creeping Privatization through Takeover Zone Models .............................................................14 Funding the Privatization Movement ..........................................................................................17 Charter Backers Broaden Support to Embrace Personalized Learning ....................................21 National Donors as Longtime Players in Massachusetts ...........................................................25 The Pioneer Institute ....................................................................................................................29 Profits or Professionals? Tech Products Threaten the Future of Teaching ....... 35 Personalized Profits: The Market Potential of Educational Technology Tools ..........................39 State-Funded Personalized Push in Massachusetts: MAPLE and LearnLaunch ....................40 Who’s Behind the MAPLE/LearnLaunch Collaboration? ...........................................................42 Gates -

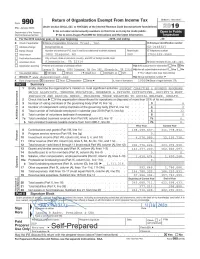

Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check If Schedule O Contains a Response Or Note to Any Line in This Part III

Form 990 (2019) Page 2 Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check if Schedule O contains a response or note to any line in this Part III . 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission: SUPPORT CHARITIES & SPONSOR PROGRAMS WHICH ALLEVIATE, THROUGH EDUCATION, RESEARCH & PRIVATE INITIATIVES, SOCIETY'S MOST PERVASIVE AND RADICAL NEEDS, INCLUDING THOSE RELATING TO SOCIAL WELFARE, HEALTH, 2 Did the organization undertake any significant program services during the year which were not listed on the prior Form 990 or 990-EZ? ........................... Yes No If “Yes,” describe these new services on Schedule O. 3 Did the organization cease conducting, or make significant changes in how it conducts, any program services? ................................. Yes No If “Yes,” describe these changes on Schedule O. 4 Describe the organization’s program service accomplishments for each of its three largest program services, as measured by expenses. Section 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations are required to report the amount of grants and allocations to others, the total expenses, and revenue, if any, for each program service reported. 4 a (Code: ) (Expenses $ 163,183,043. including grants of $ 161,930,479. ) (Revenue $0. ) DAF PROGRAM - A DONOR ADVISED FUND (DAF) PROGRAM ALLOWING DAF CONTRIBUTORS TO ADVISE GRANTS THAT SUPPORT CHARITIES WHICH ALLEVIATE, THROUGH EDUCATION, RESEARCH AND PRIVATE INITIATIVES, SOCIETY'S MOST PERVASIVE AND RADICAL NEEDS, INCLUDING THOSE RELATING TO SOCIAL WELFARE, HEALTH, ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMICS, GOVERNANCE, FOREIGN RELATIONS AND ARTS AND CULTURE; AND WHICH ENCOURAGE PRIVATE PHILANTHROPY AND INDIVIDUAL GIVING AND RESPONSIBILITY AS AN ANSWER TO SOCIETY'S NEEDS, AS OPPOSED TO GOVERNMENTAL INVOLVEMENT. -

Department of Political Science Bachelor in Politics Philosophy And

! ! Department of Political Science Bachelor in Politics Philosophy and Economics Chair in Sociology CLIMATE CHANGE DENIAL: THE OTHER SIDE OF THE COIN OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION SUPERVISOR: STUDENT: Prof. Lorenzo De Sio Stella Levantesi 073092 ACADEMIC YEAR 2015/2016 Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………Page 3 Chapter 1: Climate Change and Climate Change Denial……………………...Page 5 Chapter 2: The History of Climate Change Denial……………………………Page 12 Chapter 3: The Actors and Funding of Climate Change Denial………………Page 21 Chapter 4: Climate Change Denial Arguments and Strategies………………..Page 35 Chapter 5: Climate Change Denial Outside the US…………………………...Page 44 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………….Page 48 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………..Page 50 Summary in Italian……………………………………………………………Page 54 ! 2! Introduction Just recently, at the end of 2015, the oil giant ExxonMobil was put under investigation over claims it lied about climate change risks1. The New York attorney general is investigating whether ExxonMobil misinformed its investors and the public on the threats of climate change and the potential risks of business prospects involved in it2. Democratic presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders both demanded for investigations into Exxon, after exposure on Exxon’s conduct3. In fact, it seems Exxon knew about the dangers of climate change for ages, but continued to sow doubt about climate science. It must be seen whether such action could amount to fraud and violations of environmental laws. A report issued by Greenpeace (2010) revealed the company had spent more than $30 million casting doubt about scientific evidence on climate change, before making a public commitment in 2008 to end such funding of climate change denial activities4. However, Exxon continued to fund denial groups and campaigns through secretive donors, or simply off the record in a covert manner (Greenpeace, 2010). -

How Right Wing Funders Are Manufacturing News and Influencing Public Policy in Pennsylvania

Driving the News How right wing funders are manufacturing news and influencing public policy in Pennsylvania A Report by Keystone Progress August, 2013 This report was produced by Keystone Progress. Keystone Progress is Pennsylvania’s largest progressive advocacy organization with over 350,000 subscribers. Keystone Progress embraces a pragmatic and flexible approach to advancing equal opportunity for all, the protection of individual freedoms, and democratic, transparent and people-oriented (rather than corporate) government. We support every worker’s right to organize and earn a living wage, every individual’s right to control their reproductive health options, every child’s right to public education, and every human being’s right to breathe clean air, drink clean water, and access adequate health care, food and shelter. [email protected] 610-990-6300 2 Executive Summary There is a disturbing new movement to supplant genuine investigative reporting with pseudo-reporting by right-wing advocacy organizations. These advocacy groups, posing as legitimate news bureaus, are well funded and have become accepted as objective news organizations by many mainstream newspapers, television and radio news operations. In fact, one such network claims that it is already "provides 10 percent of all daily reporting from state capitals nationwide."i This insidious infiltration of legitimate news operations is led by the Franklin Center for Government and Public Integrity. Its local affiliate in Pennsylvania is the Pennsylvania Independent. Key Findings . Despite its claims, the Pennsylvania Independent is far from being independent or unbiased. The Pennsylvania Independent is run by the far-right Franklin Center for Government and Public Integrity, which has close ties to the American Legislative Exchange Council, the Koch brothers, the Tea Party, the Conservative Political Action Conference, the Heritage Foundation and numerous other conservative causes and candidates.