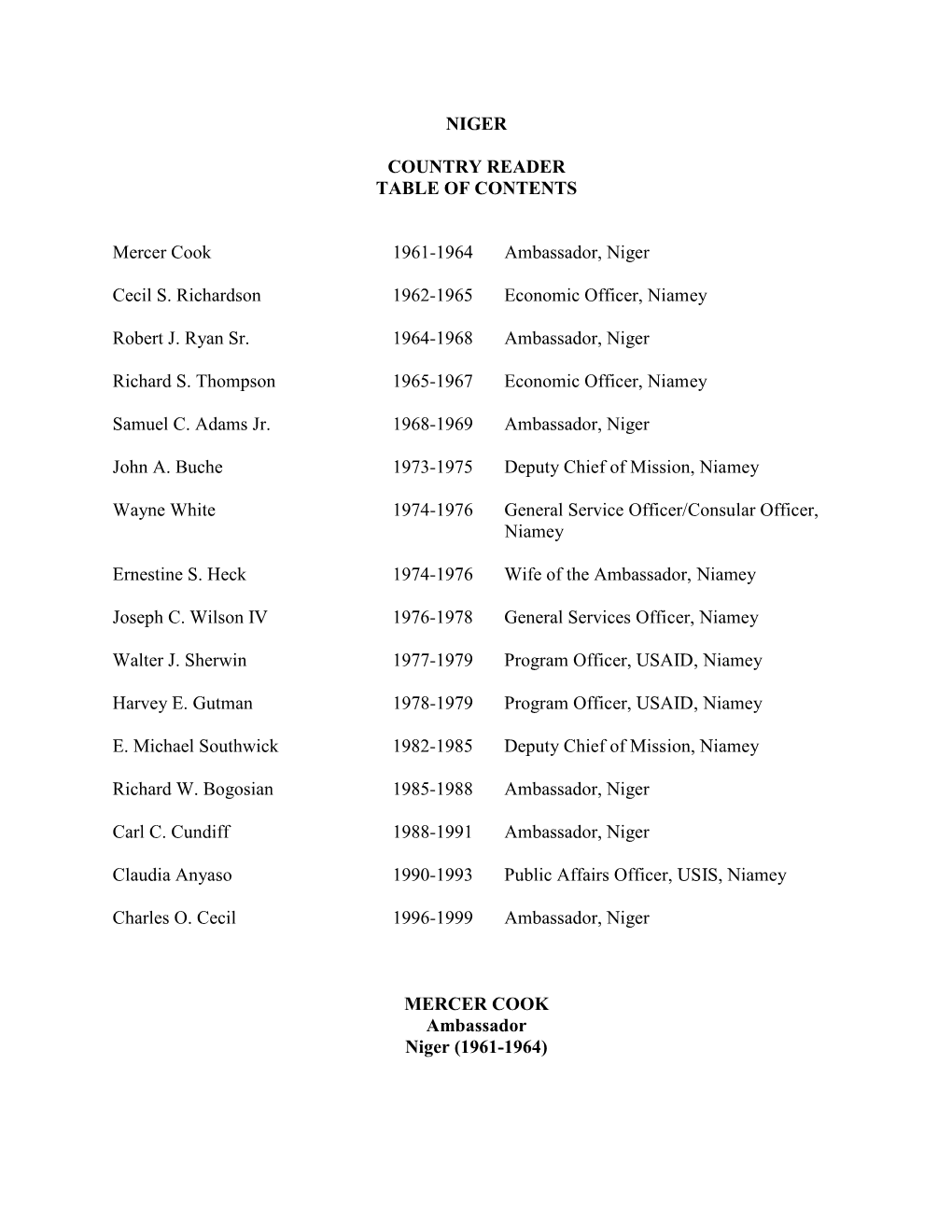

NIGER COUNTRY READER TABLE of CONTENTS Mercer Cook 1961

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Narrative and Meaning of Sawaba's Rebellion in Niger

Sawaba's rebellion in Niger (1964-1965): narrative and meaning Walraven, K. van; Abbink, G.J.; Bruijn, M.E. de Citation Walraven, K. van. (2003). Sawaba's rebellion in Niger (1964-1965): narrative and meaning. In G. J. Abbink & M. E. de Bruijn (Eds.), African dynamics (pp. 218-252). Leiden: Brill. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12903 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12903 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 9 Sawaba’s rebellion in Niger (1964-1965): Narrative and meaning Klaas van Walraven One of the least-studied revolts in post-colonial Africa, the invasion of Niger in 1964 by guerrillas of the outlawed Sawaba party was a dismal failure and culminated in a failed attempt on the life of President Diori in the spring of 1965. Personal aspirations for higher education, access to jobs and social advancement, probably constituted the driving force of Sawaba’s rank and file. Lured by the party leader, Djibo Bakary, with promises of scholarships abroad, they went to the far corners of the world, for what turned out to be guerrilla training. The leadership’s motivations were grounded in a personal desire for political power, justified by a cocktail of militant nationalism, Marxism-Leninism and Maoist beliefs. Sawaba, however, failed to grasp the weakness of its domestic support base. The mystifying dimensions of revolutionary ideologies may have encouraged Djibo to ignore the facts on the ground and order his foot soldiers to march to their deaths. -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

COUNTRY ANALYSES and PLANS Niger NIGER

COUNTRY ANALYSES AND PLANS Niger NIGER $104M of CapEx funding and $96M of annual OpEx funding will enable Niger to connect over 19,000 schools This investment will bring 3.5 million students and teachers online and bring connectivity to 7.2 million community members who live locally, potentially enabling over 525 million USD of GDP growth, a 1.8% increase. Source: Dalberg Analysis based on Giga mapping and modelling data, 2020 NIGER “The Giga initiative is a great project for us because it comes to complement the already existing efforts we had of last mile connectivity to different essential services like schools.” IBRAHIMA GUIMBA-SAÏDOU Director, ANSI & Minister | Special Advisor NIGER Mobile coverage has steadily increased over the last 5 years, further connectivity is required to achieve rural development plans In the last 5 years mobile broadband coverage has grown The Government of Niger is aiming to drive economic growth through but internet use has lagged behind digitization with universal access to connectivity Broadband coverage and internet penetration, % of Niger hopes to achieve this target through the following internet population. (ITU, 2020) connectivity and education policies: 100 • Renaissance Act II Program: The President’s 2016 reform program envisages 3G Coverage an improvement in the quality of public services by improving digital Internet users1 communication within society. This led to the creation of National Agency for 80 Information Systems (ANSI) and the strategic vision "NIGER 2.0“ Airtel became the first 4G -

Niger Country Brief: Property Rights and Land Markets

NIGER COUNTRY BRIEF: PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS Yazon Gnoumou Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison with Peter C. Bloch Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison Under Subcontract to Development Alternatives, Inc. Financed by U.S. Agency for International Development, BASIS IQC LAG-I-00-98-0026-0 March 2003 Niger i Brief Contents Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Purpose of the country brief 1 1.2 Contents of the document 1 2. PROFILE OF NIGER AND ITS AGRICULTURE SECTOR AND AGRARIAN STRUCTURE 2 2.1 General background of the country 2 2.2 General background of the economy and agriculture 2 2.3 Land tenure background 3 2.4 Land conflicts and resolution mechanisms 3 3. EVIDENCE OF LAND MARKETS IN NIGER 5 4. INTERVENTIONS ON PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS 7 4.1 The colonial regime 7 4.2 The Hamani Diori regime 7 4.3 The Kountché regime 8 4.4 The Rural Code 9 4.5 Problems facing the Rural Code 10 4.6 The Land Commissions 10 5. ASSESSMENT OF INTERVENTIONS ON PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKET DEVELOPMENT 11 6. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 13 BIBLIOGRAPHY 15 APPENDIX I. SELECTED INDICATORS 25 Niger ii Brief NIGER COUNTRY BRIEF: PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS Yazon Gnoumou with Peter C. Bloch 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE COUNTRY BRIEF The purpose of the country brief is to determine to which extent USAID’s programs to improve land markets and property rights have contributed to secure tenure and lower transactions costs in developing countries and countries in transition, thereby helping to achieve economic growth and sustainable development. -

NER N3051 4.Pdf

Hamani Diori President of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of the Niger Bornbeganin his1916careerin Niger,as a teacher.Hamani InDiori1952graduatedhe becamefromthetheprincipalEcole ofNormalea schoolin inDakarNiamey.and In 1946,he founded the Niger Progressive Party (P. P. N. ), local division of the African Democratic Rally (R.D.A.). Mr. Diori served as Deputy from Niger to the French National Assembly from 1946 to 1951, and again from 1956 to 1958. He became Vice President of that Assembly on June 21, 1957 and remained in that post until December 1958. In March 1958, Mr. Diori was a member of the French Delegation to the European Parliamentary Assembly. When, on December 18, 1958, Niger chose the status of self-governing Republic and member State of the Community, Mr. Diori became President of the Provisional Government. Following adoption of the Niger's Constitution on February 25, 1959 by the Constituent Assembly, the Republic of the Niger formed its first Government and Mr. Diori was con¬ firmed as President of the Council of Ministers. (o M - H Zg TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE The Republic of the Niger 3 Highlights of History and Recent Political Evolution 6 The Land and the People 8 Social and Cultural Development 13 Education 13 Public Health 16 Social Legislation 17 The Economy 18 Cash Crops 21 Stock Raising 24 Industry 28 Transportation 29 Foreign Trade 32 rTHE REPUBLIC OF THE NIGER A Modern Democratic State In 78%the Referendumvote in favorofofSeptemberthe Constitution28, 1958,drawnthe peopleup by Generalof Niger dereturnedGaulle'sa Government, offering the Overseas Territories of the French Republic a choice between several possible statuses. -

Caught in the Middle a Human Rights and Peace-Building Approach to Migration Governance in the Sahel

Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar CRU Report Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin CRU Report December 2018 December 2018 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: © Jérôme Tubiana. Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the authors Fransje Molenaar is a Senior Research Fellow with Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit, where she heads the Sahel/Libya research programme. She specializes in the political economy of (post-) conflict countries, organized crime and its effect on politics and stability. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THE POLITICS OF ELECTORAL REFORM IN FRANCOPHONE WEST AFRICA: THE BIRTH AND CHANGE OF ELECTORAL RULES IN MALI, NIGER, AND SENEGAL By MAMADOU BODIAN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Mamadou Bodian To my late father, Lansana Bodian, for always believing in me ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want first to thank and express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Leonardo A. Villalón, who has been a great mentor and good friend. He has believed in me and prepared me to get to this place in my academic life. The pursuit of a degree in political science would not be possible without his support. I am also grateful to my committee members: Bryon Moraski, Michael Bernhard, Daniel A. Smith, Lawrence Dodd, and Fiona McLaughlin for generously offering their time, guidance and good will throughout the preparation and review of this work. This dissertation grew in the vibrant intellectual atmosphere provided by the University of Florida. The Department of Political Science and the Center for African Studies have been a friendly workplace. It would be impossible to list the debts to professors, students, friends, and colleagues who have incurred during the long development and the writing of this work. Among those to whom I am most grateful are Aida A. Hozic, Ido Oren, Badredine Arfi, Kevin Funk, Sebastian Sclofsky, Oumar Ba, Lina Benabdallah, Amanda Edgell, and Eric Lake. I am also thankful to fellow Africanists: Emily Hauser, Anna Mwaba, Chesney McOmber, Nic Knowlton, Ashley Leinweber, Steve Lichty, and Ann Wainscott. -

Threat Analysis

Threat analysis: West African giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis peralta) in Republic of Niger April 2020 Kateřina Gašparová1, Julian Fennessy2, Thomas Rabeil3 & Karolína Brandlová1 1Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Kamýcká 129, 165 00 Praha Suchdol, Czech Republic 2Giraffe Conservation Foundation, Windhoek, Namibia 3Wild Africa Conservation, Niamey, Niger Acknowledgements We would like to thank the Nigerien Wildlife Authorities for their valuable support and for the permission to undertake the work. Particularly, we would like to thank the wildlife authorities’ members and rangers. Importantly, we would like to thank IUCN-SOS and European Commission, Born Free Foundation, Ivan Carter Wildlife Conservation Alliance, Sahara Conservation Fund, Rufford Small Grant, Czech University of Life Sciences and GCF for their valuable financial support to the programme. Overview The Sudanian savannah currently suffers increasing pressure connected with growing human population in sub-Saharan Africa. Human settlements and agricultural lands have negatively influenced the availability of resources for wild ungulates, especially with increased competition from growing numbers of livestock and local human exploitation. Subsequently, and in context of giraffe (Giraffa spp.), this has led to a significant decrease in population numbers and range across the region. Remaining giraffe populations are predominantly conserved in formal protected areas, many of which are still in the process of being restored and conservation management improving. The last population of West African giraffe (G. camelopardalis peralta), a subspecies of the Northern giraffe (G. camelopardalis) is only found in the Republic of Niger, predominantly in the central region of plateaus and Kouré and North Dallol Bosso, about 60 km south east of the capital – Niamey, extending into Doutchi, Loga, Gaya, Fandou and Ouallam areas (see Figure 1). -

Niger: Frequently Asked Questions About the October 2017 Attack on U.S

Niger: Frequently Asked Questions About the October 2017 Attack on U.S. Soldiers Alexis Arieff, Coordinator Specialist in African Affairs Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs Andrew Feickert Specialist in Military Ground Forces Kathleen J. McInnis Analyst in International Security John W. Rollins Specialist in Terrorism and National Security Matthew C. Weed Specialist in Foreign Policy Legislation October 27, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44995 Niger: Frequently Asked Questions About the October 2017 Attack on U.S. Soldiers Summary A deadly attack on U.S. soldiers in Niger and their local counterparts on October 4, 2017, has prompted many questions from Members of Congress about the incident. It has also highlighted a range of broader issues for Congress pertaining to oversight and authorization of U.S. military deployments, evolving U.S. global counterterrorism activities and strategy, interagency security assistance and cooperation efforts, and U.S. engagement with countries historically considered peripheral to core U.S. national security interests. This report provides background information in response to the following frequently asked questions: What is the security situation in Niger? How big is the U.S. military presence in Niger? For what purposes are U.S. military personnel in Niger, and what role has Congress played in the U.S. military presence there? Is the U.S. military presence in Niger related to the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF)? What is the state of U.S.-Niger relations and aid? Where else in Africa are U.S. military personnel deployed? Medical evacuation: What is the “golden hour” and does it apply to troop deployments in Africa? What are the broader implications of building partner capacity in Niger for DOD? Who were the four U.S. -

Natiolnal DEMOCRATIC INS'l'l'l'u'l'e '

NATIOlNAL DEMOCRATIC INS'l'l'l'U'l'E' - FOR INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS FA.. (202) 939-3 166 Fihh Fhr. I-1- Yrruchtwttr lrmw. Y.W. Washington. D.C. 2W.W (202) .W?-llZb H E-Mail 5Ym0~9@htCIMAILCOht AREAF Project Find Report DEMOCRATIC CONSOILIDATION IN NIGER, MALI AND BENIN THE ROLE OF AN EFFECTIVE LEGISLATURE Grant No. AOT-0486-A-00-2134-00 Modification #I0 January 1 to September 30, 1994 AREAF Project Final Report DEMOCRATIC CONSOLIDATION IN NIGER, MALI AND BENIN THE ROLE OF AN EFFECTIVE LEGISLATURE Grant No. AOT-0486-A-00-2134-00 Modification #10 January 1 to September 30, 1994 I. INTRODUCTION The National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) organized a legislative rogram program in Niamey, Niger, for deputies from the national assemblies of Benin, Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. The primary objective of the seminar was to increase the effectiveness of these nascent assemblies and to assist the process of consolidating democratic governance in these countries. The program was planned in direct response to requests for assistance from newly elected representatives of three of the national assemblies. The program was designed in three parts: an advance visit by a small team of NDI staff and a parliamentary expert to plan for the seminar and develop a specific agenda; the seminar itself and a follow-up presence by an NDI field representative to assess the project and assist in initiatives that may have flown from the seminar. The seminar provided an opportunity for the West African participants to address problems common to their fledgling legislstures. -

PNAAJ203.Pdf

PN-MJ203 EDa-000-C 212 'Draft enviromnental report on Niger Speece, Mark Ariz. Univ. Office of Arid Lands Studies 6. IXOCUMVT DATE (110) )7.NJMDER OF1 P. (125) II. R NIR,(175) 19801 166p. NG330.96626. S742 9. EFERENZE ORGANIZATIUN (150) Ariz. 10. SUPLMENTAiY Na1M (500) (Sponsored by AID through the U. S. National Committee for Man and the Biosphere) 11. ABSTRACT (950) 12. D SCKWrOR5 (o20) ,. ?mj3Cr N (iS5 ' Niger Enviironmental factors Soil erosion 931015900 Desertification Deforestation 14. WRiA .414.) IL Natural resources Water resources Water supply Droughts AID/ta-G-11t1 wnmiwommmr 4, NG6 sq~DRAFT ErWIROHIITAL REPORT ON NIGER prepared by the Arid Lands Information Center Office of Arid Lands Studies University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 ,National Park Service Contract No. CX-0001-0-0003 with U.S. Man and the Biosphere Secretariat Department of Stati Washington, D.C. Septmber 1980 2.0 Hmtu a ReOe$4 , 9 2.1 OU6era Iesources and Energy 9 2. 1.1",Mineral Policy 11 2.1.2 Ainergy 12 2.2 Water 13 2.2.1 Surface Water 13 2.2.2 Groundwater I: 2.2.3 Water Use 16 2.2.4 Water Law 17 2.3 Soils and Agricultural Land Use 18 2.3.1 Soils 18 2.3.2 Agriculture 23 2.4 Vegetation 27 2.4.1 Forestry 32 2.4.2 Pastoralism 33 2.5 Fau, and Protected Areas 36 2.5.1 Endangered Species 38 2.5.2 Fishing 38 3.0 Major Environmental Problems 39 3.1 Drouqht 39 3.2 Desertification 40 3.3 Deforestation and Devegetation 42 3.4 Soil Erosion and Degradation 42 3.5 Water 43 4.0 Development 45 Literature Cited 47 Appendix I Geography 53 Appendix II Demographic Characteristics 61 Appendix III Economic Characteristics 77 Appendi" IV List of U.S. -

Table of Contents

NIGER COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Mercer Cook 1961-1964 Ambassador, Niger Cecil S. Richardson 1962-1965 Economic Officer, Niamey Robert J. Ryan Sr. 1964-1968 Ambassador, Niger Richard S. Thompson 1965-1967 Economic Officer, Niamey Samuel C. Adams Jr. 1968-1969 Ambassador, Niger John A. Buche 1973-1975 Deputy Chief of Mission, Niamey Wayne White 1974-1976 General Service Officer/Consular Officer, Niamey Ernestine S. Heck 1974-1976 Wife of the Ambassador, Niamey Joseph C. Wilson IV 1976-1978 General Services Officer, Niamey Walter J. Sherwin 1977-1979 Program Officer, USAID, Niamey Richard C. Howland 1978 Office of the Inspector General, Washington, DC Harvey E. Gutman 1978-1979 Program Officer, USAID, Niamey Susan Keogh 1978-1980 Spouse of Deputy Chief of Mission, Niamey E. Michael Southwick 1982-1985 Deputy Chief of Mission, Niamey Albert E. Fairchild 1985-1987 Deputy Chief of Mission, Niamey Richard W. Bogosian 1985-1988 Ambassador, Niger Carl C. Cundiff 1988-1991 Ambassador, Niger Claudia Anyaso 1990-1993 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Niamey Charles O. Cecil 1996-1999 Ambassador, Niger 1 MERCER COOK Ambassador Niger (1961-1964) Ambassador Cook was born and raised in Washington D.C. and educated at Amherst College and the Universities of Paris and Brown. During his career as a professor of romance languages, the Ambassador served on the faculties of Atlanta University, the University of Haiti and Howard University. In 1961 he was appointed US Ambassador to Niger, where he served until May, 1964. That year he was appointed Ambassador to Senegal and Gambia, residing at Dakar, where he served until July, 1966.