The Didache and Traditioned Innovation: Shaping Christian Community in the First Century and the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tradition of the Female Deacon in the Eastern Churches

The Tradition of the Female Deacon in the Eastern Churches Valerie Karras, Th.D., Ph.D. and Caren Stayer, Ph.D. St. Phoebe Center Conference on “Women and Diaconal Ministry in the Orthodox Church: Past, Present, and Future” Union Theological Seminary, New York, NY December 6, 2014 PURPOSE OF HISTORY SESSION • To briefly review the scholarship on the history of the deaconess, both East and West • To lay the groundwork for discussions later in the day about the present and future • To familiarize everyone with material you can take with you • Book list; book sales • We ask you to share and discuss this historical material with others in your parish TIMELINE—REJUVENATION FROM PATRISTIC PERIOD (4TH -7TH C.) • Apostolic period (AD 60-80): Letters of Paul (Rom 16:1 re Phoebe) • Subapostolic period (late 1st/early 2nd c.): deutero-Pauline epistles (I Tim. 3), letter of Trajan to Pliny the Younger • Byzantine period (330-1453) − comparable to Early, High, and Late Middle Ages plus early Renaissance in Western Europe • Early church manuals (Didascalia Apostolorum, late 3rd/early 4th c.; Testamentum Domini, c.350; Apostolic Constitutions, c.370, Syriac) • 325-787: Seven Ecumenical Councils • Saints’ lives, church calendars, typika (monastic rules), homilies, grave inscriptions, letters • 988: conversion of Vladimir and the Rus’ • 12th c. or earlier: office of deaconess in Byz. church fell into disuse • Early modern period in America • 1768: first group of Greek Orthodox arrives in what is now Florida • 1794: first formal Russian Orthodox mission arrives in what is now Alaska BYZANTINE EMPIRE AND FIVE PATRIARCHATES CIRCA 565 A.D. -

Paper for the Oxford Institute of Methodist Theological Studies, August 2007 History of Methodism Working Group

Paper for the Oxford Institute of Methodist Theological Studies, August 2007 History of Methodism Working Group A Calling to Fulfill: Women in 19th Century American Methodism Janie S. Noble In Luke’s account of the resurrection, it is women, Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the other women who take the message of the empty tomb to the apostles (24:10).1 The Old and New Testaments provide other witnesses to women’s involvement in a variety of ministries; the roles for women in the church through time have been equally as varied. Regardless of the official position of the church regarding their roles, women have remained integral to continuation of our faith. Historical restrictions on the involvement of women have been justified both scripturally and theologically; arguments supporting their involvement find the same bases. Even women who stand out in history often did not challenge the practices of their times that confined women to home, family, or the convent. For example, Hildegard of Bingen is considered a model of piety and while she demonstrated courage in her refusal to bend to the demands of clergy, she was not an advocate of change or of elevation of women’s authority in the church. Patristic attitudes have deep roots in the Judeo-Christian traditions and continue to affect contemporary avenues of ministry available to women. Barriers for women in America began falling in the nineteenth century as women moved to increasingly visible activities outside the home. However, women’s ascent into leadership roles in the church that matched the roles of men was much slower than in secular areas. -

The Following Article on How Religions Use Water in Rituals Is Recommended Reading Especially for Week I

Lenten Study Reading Material: Week One The following article on how religions use water in rituals is recommended reading especially for Week I. Baha'i Water is fundamental in the rites, language and symbolism of all religions, and the Bahá'í Faith is no exception. There are Bahá'í laws concerning water and cleanliness, and many ways that water is used as a metaphor for spiritual truths. This brief summary of the Bahá'í perspective on water is based as far as possible on direct quotations from the Bahá'í Writings. (Full article by Arthur Lyon Dahl) In a more general context, the Bahá'í Faith places great importance on agriculture and the preservation of the ecological balance of the world. Water is of course a fundamental resource for agriculture. It is essential to the functioning of all ecological communities and plays a key role in all the life support systems of the planet. It is essential to life itself, which is why it is so often used in spiritual symbolism. Water is an important medium for linking us with the environment in the complex interactions that are such an important feature of our integrated planetary system. For Bahá'ís, respect for the creation in all its beauty and diversity is important, and water is a key element of that creation. "The Almighty Lord is the provider of water, and its maker, and hath decreed that it be used to quench man's thirst, but its use is dependent upon His Will. If it should not be in conformity with His Will, man is afflicted with a thirst which the oceans cannot quench." (`Abdu'l-Bahá, in Prayer, Meditation, and the Devotional Attitude (compilation), pages 231-232) Lenten Study Reading Material: Week One The wise management of all the natural resources of the planet, including water, will require a global approach, since water is not a respecter of national boundaries. -

History of Christian Doctrine Vol 1.Pdf

A HISTORYof Christian Doctrine The Post–Apostolic Age to the Middle Ages A . D . 100–1500 Volume 1 David K. Bernard A HISTORYof Christian Doctrine The Post–Apostolic Age to the Middle Ages A . D . 100–1500 Volume 1 A History of Christian Doctrine, Volume One The Post-Apostolic Age to the Middle Ages, A.D. 100-1500 by David K. Bernard ISBN 1-56722-036-3 Cover Design by Paul Povolni ©1995 David K. Bernard Hazelwood, MO 63042-2299 All Scripture quotations in this book are from the King James Version of the Bible unless otherwise identified. All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in an electronic system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of David K. Bernard. Brief quotations may be used in literary reviews. Printed in United States of America Printed by Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bernard, David K., 1956– A history of Christian doctrine / by David K. Bernard. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: v. 1. The Post-Apsotolic Age to the Middle Ages, A.D. 100-1500. ISBN 1-56722-036-3 (pbk.) 1. Theology, Doctrinal—History. 2. Church history. 3. Oneness doctrine (Pentecostalism)—History. I. Title. BT 21.2.B425 1995 230'.09—dc20 95-35396 CIP Contents Preface . 7 1. The Study of Doctrine in Church History . 9 2. Early Post-Apostolic Writers, A.D. 90-140 . 21 3. Early Heresies . 31 4. The Greek Apologists, A.D. 130-180 . -

Procedures for Reverencing the Tabernacle and the Altar Before, During and After Mass

Procedures for Reverencing the Tabernacle and the Altar Before, During and After Mass Key Terms: Eucharist: The true presence of Christ in the form of his Body and Blood. During Mass, bread and wine are consecrated to become the Body and Blood of Christ. Whatever remains there are of the Body of Christ may be reserved and kept. Tabernacle: The box-like container in which the Eucharistic Bread may be reserved. Sacristy: The room in the church where the priest and other ministers prepare themselves for worship. Altar: The table upon which the bread and wine are blessed and made holy to become the Eucharist. Sanctuary: Often referred to as the Altar area, the Sanctuary is the proper name of the area which includes the Altar, the Ambo (from where the Scriptures are read and the homily may be given), and the Presider’s Chair. Nave: The area of the church where the majority of worshippers are located. This is where the Pews are. Genuflection: The act of bending one knee to the ground whilst making the sign of the Cross. Soon (maybe even next weekend – August 25-26) , the tabernacle will be re-located to behind the altar. How should I respond to the presence of the reserved Eucharist when it will now be permanently kept in the church sanctuary? Whenever you are in the church, you are in a holy place, walking upon holy ground. Everyone ought to be respectful of Holy Rosary Church as a house of worship and prayer. Respect those who are in silent prayer. -

CHAPTER 2 CHRISTIAN INITIATION of ADULTS and CHILDREN of CATECHETICAL AGE I. INTRODUCTION 2.1.1 out of the Baptismal Font, Chri

CHAPTER 2 CHRISTIAN INITIATION OF ADULTS AND CHILDREN OF CATECHETICAL AGE I. INTRODUCTION 2.1.1 Out of the baptismal font, Christ the Lord generates children to the Church who bear the image of the resurrected one. United to Christ in the Holy Spirit, they are rendered fit to celebrate with Christ the sacred liturgy, spiritual worship.123 2.1.2 “This bath is called enlightenment, because those who receive this instruction are enlightened in their understanding....” Having received in baptism the Word, “the true light that enlightens every man,” the person baptized has been “enlightened,” he becomes a “son of light,” indeed, he becomes “light” himself: “Baptism is God’s most beautiful and magnificent gift.... We call it gift, grace, anointing, enlightenment, garment of immortality, bath of rebirth, seal, and most precious gift. It is called gift because it is conferred on those who bring nothing of their own; grace since it is given even to the guilty; baptism because sin is buried in the water; anointing for it is priestly and royal as are those who are anointed; enlightenment because it radiates light; clothing since it veils our shame; bath because it washes; and seal as it is our guard and the sign of God’s Lordship.”124 2.1.3 From the time of the Apostles, becoming a Christian has been accomplished by a journey and initiation in several stages. This journey can be covered rapidly or slowly, but certain essential elements will always have to be present: proclamation of the Word, acceptance of the Gospel entailing conversion, profession of faith, baptism itself, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, and admission to Eucharistic Communion.125 2.1.4 The image of the journey of faith is clearly evident in the Church’s ritual for the initiation of adults and older children. -

The Place of the Local Preacher in Methodism

Wofford College Digital Commons @ Wofford Historical Society Addresses Methodist Collection 12-7-1909 The lP ace of the Local Preacher in Methodism Joseph B. Traywick Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/histaddresses Part of the Church History Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Traywick, Joseph B., "The lP ace of the Local Preacher in Methodism" (1909). Historical Society Addresses. Paper 14. http://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/histaddresses/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Methodist Collection at Digital Commons @ Wofford. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Society Addresses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Wofford. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Place of the Local Preacher in Methodism With Sketches of the Lives of Some Representative Local Preachers of the South Carolin'a Conference BY REV. JOSEPH B. TRAYWICK An Address Delivered Before the Historical Society of the South Carolina Conference, Methodist Episcopal Church, South, in Abbeville, S. C ., December 7, 1909. \ The origin of local preachers and their work in Methodi sm, like all else in that great SI)irituai awakening, was Providential. The work at the Foundry in London had been inaugurateu by Mr. Wesley for some lime. When he must needs be away for awhile. he nppoillted Thomas Maxfield. a gifted layman, to hold prayer meetings in hi s absence. But Maxfield's exhortations proved to be preaching with great effect. On Mr. Wesley's return, he was alarmed Jest he hOld gone too far; but the wise counsel of his mother served him well at thi s critical h OUT in the great movement. -

Understanding When to Kneel, Sit and Stand at a Traditional Latin Mass

UNDERSTANDING WHEN TO KNEEL, SIT AND STAND AT A TRADITIONAL LATIN MASS __________________________ A Short Essay on Mass Postures __________________________ by Richard Friend I. Introduction A Catholic assisting at a Traditional Latin Mass for the first time will most likely experience bewilderment and confusion as to when to kneel, sit and stand, for the postures that people observe at Traditional Latin Masses are so different from what he is accustomed to. To understand what people should really be doing at Mass is not always determinable from what people remember or from what people are presently doing. What is needed is an understanding of the nature of the liturgy itself, and then to act accordingly. When I began assisting at Traditional Latin Masses for the first time as an adult, I remember being utterly confused with Mass postures. People followed one order of postures for Low Mass, and a different one for Sung Mass. I recall my oldest son, then a small boy, being thoroughly amused with the frequent changes in people’s postures during Sung Mass, when we would go in rather short order from standing for the entrance procession, kneeling for the preparatory prayers, standing for the Gloria, sitting when the priest sat, rising again when he rose, sitting for the epistle, gradual, alleluia, standing for the Gospel, sitting for the epistle in English, rising for the Gospel in English, sitting for the sermon, rising for the Credo, genuflecting together with the priest, sitting when the priest sat while the choir sang the Credo, kneeling when the choir reached Et incarnatus est etc. -

Synoptic Traditions in Didache

Synoptic Tradition in the Didache Revisited Dr. Aaron Milavec Center for the Study of Religion and Society University of Victoria Ever since a complete copy of the Didache was first discovered in 1873, widespread efforts have been undertaken to demonstrate that the framers of the Didache depended upon a known Gospel (usually Matthew, Luke, or both) and upon one or more Apostolic Fathers (Barnabas, Hermas, and/or Justin Martyr). In more recent times, however, most scholars have pushed back the date of composition to the late first or early second century and called into question dependency upon these sources. In the late 50s, Audet1. Glover2, and Koester3 cautiously developed this stance independent of each other. More recently, Draper4, Kloppenborg5, Milavec6, Niederwimmer7, Rordorf8, and Van de Sandt9 have argued quite persuasively in favor of this position. Opposition voices, however, are still heard. C.M. Tuckett10 of Oxford University, for example, reexamined all the evidence in 1989 and came to the conclusion that parts of the Didache "presuppose the redactional activity of both evangelists" thereby reasserting an earlier position that "the Didache here presupposes the gospels of Matthew and Luke in their finished forms."11 Clayton N. Jefford, writing in the same year independent of Tuckett, came to the conclusion that the Didache originated in the same community that produced the Gospel of Matthew and that both works had common sources but divergent purposes.12 Vicky Balabanski, in a book-length treatment of the eschatologies of Mark, Matthew, and Didache, reviewed all the evidence up until 1997 and concluded that Did. 16 was written "to clarify and specify certain aspects of Matthew's eschatology."13 This essay will weigh the evidence for and against dependence upon the Gospel of Matthew--the most frequently identified "written source" for the Didache. -

Simple Catechism in Question-And-Answer Form [ Know and Love Your Catholic Faith \

A Simple Catechism in Question-and-Answer Form [ Know and Love Your Catholic Faith \ Download, Print, Propagate. www.TheCatholicFaith.info Holiness Through Truth ✠ A Simple Catechism A Catholic Faith Booklet Download, Print, Propagate. www.thecatholicfaith.info Dedicated to St. Francis de Sales About this booklet: This booklet is directed to all Catholic lay faithful, young and old, to mobilise the ‘sleeping giant’ of the Church by helping them to know and love their faith. It is The Catholic Faith edition of the ‘Penny Catechism’, which features a few minor changes including updating of terminologies (QQ. 319, 321, 324, etc.) and dates (Q. 231), formatting improvements, and the addition of the five Luminous Mysteries (p. 59), introduced by Pope John Paul II in 2002. This version was last edited on October 20, 2013. Basic Catechism Of Christian Doctrine (4 Week Meditation Cycle) sourced with permission from: www.memorare.com with: Imprimatur ✠ John Cardinal Heenan Archbishop of Westminster 18 July 1971 Explanatory text from: The Complete Catholic Handbook www.holyspiritinteractive.net “Advance this book” - Mother Teresa of Calcutta (South Bronx, N.Y.) Permission is given to reproduce and distribute this booklet for non-profit purposes. 1 Preface The greatest commandment given to us as Catholics is to “love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind” (Matthew 22:37). As such, we must first know our faith with all our mind, for it reveals God – we cannot love what we do not know. It is for this reason that catechisms - meaning ‘oral instructions’ – developed in the early Church. -

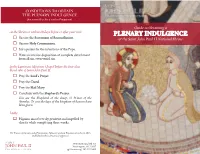

Plenary Indulgence Guide

CONDITIONS TO OBTAIN THE PLENARY INDULGENCE (for yourself or for a soul in Purgatory) Guide to Obtaining a At the Shrine or within 20 days before or after your visit: PLENARY INDULGENCE ¨¨Receive the Sacrament of Reconciliation. at the Saint John Paul II National Shrine ¨¨Receive Holy Communion. ¨¨Say a prayer for the intentions of the Pope. ¨¨Have an interior disposition of complete detachment from all sin, even venial sin. In the Luminous Mysteries Chapel before the first-class blood relic of Saint John Paul II: ¨¨Pray the Lord’s Prayer. ¨¨Pray the Creed. ¨¨Pray the Hail Mary. ¨¨Conclude with the Shepherd’s Prayer: You are the Shepherd of the sheep, O Prince of the Apostles. To you the keys of the kingdom of heaven have been given. Lastly: ¨¨Pilgrims must be truly penitent and impelled by charity while completing these works. Per Decree of the Apostolic Penitentiary Mauro Cardinal Piacenza October 3, 2016. Published with ecclesiastical approval. SAINT 3900 Harewood Rd NE OHN PAUL II Washington, DC 20017 JN ATIO N AL SHRINE jp2shrine.org | 202.635.5400 WHAT IS A PLENARY INDULGENCE? HOW CAN I OBTAIN A PLENARY INDULGENCE? “The starting-point for understanding indulgences is the The Holy Father grants a Plenary Indulgence to Christ’s faithful who make a pilgrimage to the Saint John Paul II National Shrine on one of abundance of God’s mercy revealed in the Cross of Christ. these occasions: The crucified Jesus is the great ‘indulgence’ that the Father X¨October 22 on the Solemnity of Saint John Paul II has offered humanity through the forgiveness of sins and X¨Divine Mercy Sunday (Second Sunday of Easter) the possibility of living as children in the Holy Spirit.” X¨Once a year on a day of their choice Saint John Paul II X¨Whenever they participate in a group pilgrimage God desires to forgive sins and bring us to eternal life. -

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms Liturgical Objects Used in Church The chalice: The The paten: The vessel which golden “plate” that holds the wine holds the bread that that becomes the becomes the Sacred Precious Blood of Body of Christ. Christ. The ciborium: A The pyx: golden vessel A small, closing with a lid that is golden vessel that is used for the used to bring the distribution and Blessed Sacrament to reservation of those who cannot Hosts. come to the church. The purificator is The cruets hold the a small wine and the water rectangular cloth that are used at used for wiping Mass. the chalice. The lavabo towel, The lavabo and which the priest pitcher: used for dries his hands after washing the washing them during priest's hands. the Mass. The corporal is a square cloth placed The altar cloth: A on the altar beneath rectangular white the chalice and cloth that covers paten. It is folded so the altar for the as to catch any celebration of particles of the Host Mass. that may accidentally fall The altar A new Paschal candles: Mass candle is prepared must be and blessed every celebrated with year at the Easter natural candles Vigil. This light stands (more than 51% near the altar during bees wax), which the Easter Season signify the and near the presence of baptismal font Christ, our light. during the rest of the year. It may also stand near the casket during the funeral rites. The sanctuary lamp: Bells, rung during A candle, often red, the calling down that burns near the of the Holy Spirit tabernacle when the to consecrate the Blessed Sacrament is bread and wine present there.