Martlesham Heath 199-225

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tarmac Breedon Full Text Decision

CMA/07/2018 Anticipated acquisition by Tarmac Trading Limited of certain assets of Breedon Group PLC Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition ME/6719-17 The CMA’s decision on reference under section 33(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 given on 26 April 2018. Full text of the decision published on 15 May 2018. Please note that [] indicates figures or text which have been deleted or replaced in ranges at the request of the parties for reasons of commercial confidentiality. SUMMARY 1. Tarmac Trading Limited (Tarmac) has agreed to acquire 27 ready-mix concrete (RMX) plants, a marine aggregates terminal at Briton Ferry (the Briton Ferry Wharf) as well as certain assets utilised in connection with the RMX plants and the Briton Ferry Wharf from Breedon Group PLC (Breedon) (the Merger). The acquired assets are together referred to as the Target Assets. Tarmac and the Target Assets are together referred to as the Parties. 2. The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) believes that it is or may be the case that the Parties will cease to be distinct as a result of the Merger, that the share of supply test is met and that accordingly arrangements are in progress or in contemplation which, if carried into effect, will result in the creation of a relevant merger situation. 3. The Parties overlap in the supply of: (i) primary aggregates which are used as base materials in the construction of roads, buildings, and other infrastructure, and are quarried from land or dredged from the sea; and (ii) RMX, which comprises a mix of aggregates, cement, and water supplied in ready-mix form. -

January 2009 "Vertical Short Take-Off's & Landings " 3 April 09’

What’s on Vicky Gunnell - Programme Secretary 2 January 09'........................................................... TAFF GILLINGHAM "Remembering the Great War" 6 February 09'.................Ex-BAE Systems Test Pilot - IAN WORMALD "Fifty Years Out & Back to Suffolk" 6 March 09'.......................................................................... JIM PYLE Volume 5 No.9 www.mhas.org.uk January 2009 "Vertical Short Take-off's & Landings " 3 April 09’............................From English Heritage Sarah Newsome "Suffolk's Defended Shore" Martlesham Heath Aviation Society 1 May 09'...............................Your chance to have your say - A.G.M. Plus... The Holly Hall Photo Competition 22 May 09'..........Ex-BOAC later BA Concorde Pilot - CHRIS ORLEBAR NEWSLETTER The Concorde Story, an Audio/Visual Lecture - Tickets Only President: Gordon Kinsey Newsletter Contributions If you have an article or a story you would like to share with the other members of the Society then please send it to me.... Alan Powell - Newsletter Editor Tel: Ipswich 622458 16 Warren Lane RAF Martlesham Heath Martlesham Heath Aviation Society 356th Fighter Group Martlesham Heath E-Mail Address Ipswich IP5 3SH [email protected] Other Committee Contacts... Chairman Martyn Cook (01473) 614442 Vice Chairman Bob Dunnett (01473) 624510 Secretary Alan Powell (01473) 622458 Treasurer Peter Durrell (01473) 726396 Program Sec. Vicky Gunnell (01473) 720004 Membership Sec. John Bulbeck (01473) 273326 Publicity Sec. Howard King (01473) 274300 Rag Trade David Bloomfield (01473) 686204 Catering Peter Morris (01473) 415787 Society Adviser Tom Scrivener (01473) 684636 Society Advisor Colin Whitmore (01473) 729512 Society Advisor Frank Bright (01473) 623853 Jack Russell Designs EDITORIAL A very Happy New Year to everyone. Each year I express the hope that we can live in peace, but as soon as one theatre of conflict leaves the headlines so another flashpoint occurs. -

Keep Calm and Carillion – the Company’S Pension Schemes Are More Secure Than They Look

Keep Calm and Carillion – The Company’s Pension Schemes Are More Secure than They Look Safeguarding the Carillion pension empire The company we came to know as Carillion was created in July 1999, following a demerger from Tarmac, through which it acquired a number of huge UK employers, including Mowlem and Alfred McAlpine. This gave the new company immediate responsibility for 13 defined benefit pension schemes. Almost two decades later, 27,500 people First Actuarial’s Catherine Lockyer continue to have benefits in schemes reliant on Carillion as sponsor, with close to half of sheds light on the doom and gloom these already receiving their pensions. surrounding Carillion’s pension schemes Commentators were not slow to point to The recent collapse of the construction and public problems with Carillion’s pension schemes. services contractor, Carillion plc, sent shockwaves The Guardian reported that MPs were through the British economy. accusing the company of trying to wriggle out of its pension obligations, for example. When the news broke in January, the future looked And The Economist asked whether pension uncertain for the company’s 20,000 UK employees. protection was still viable, referring to ‘a big And as industrialists took the measure of the hole’. All in all, the future of these schemes consequences for the country, other questions looked deeply uncertain, and this can only quickly emerged. have added to the anxieties of Carillion’s employees and pensioners. How would the Government deal with the huge infrastructure projects that Carillion had failed to The fantastic news, however, is that all of complete? Who would manage the maintenance Carillion’s pension scheme members have and service of hundreds of hospitals, schools and the security of the Pension Protection Fund homes? And as for the thousands of smaller (PPF). -

Phd Studentship: Research Is the Door to Tomorrow - the Post Office Research Station, Dollis Hill, C.1935-1970

H-Sci-Med-Tech PhD Studentship: Research is the Door to Tomorrow - The Post Office Research Station, Dollis Hill, c.1935-1970 Discussion published by Carsten Timmermann on Monday, June 9, 2014 An AHRC-funded Collaborative PhD Award with the University of Manchester and the Science Museum/BT Archives 'Research is the Door to Tomorrow': The Post Office Research Station, Dollis Hill, c.1935-1970 Re-advertisement: closing date 20 June 2014 Have you completed or are you close to completing a Master’s degree in History of Science and Technology, Modern History or a related field? Are you interested in twentieth century history and the role that technological R&D played in it? Do you enjoy investigating the personal stories and histories behind major developments? Would you relish the opportunity to work within a national museum? Then this could be the project for you! Applications are invited for an AHRC-funded PhD studentship on the mid-twentieth century history of the UK’s Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill, London. The studentship will commence in September 2014, and is tenable for three years’ full-time study. Owned and managed by the General Post Office, the UK’s largest state bureaucracy in the twentieth century, Dollis Hill was one of the government’s most important research establishments in electrical engineering, telecommunications and computing. By the late 1930s, it had an international reputation in an extensive network of telecommunications research, testing and manufacturing facilities encompassing other state civil -

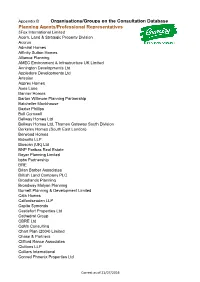

Organisations/Groups on the Consultation Database Planning

Appendix B Organisations/Groups on the Consultation Database Planning Agents/Professional Representatives 3Fox International Limited Acorn, Land & Strategic Property Division Acorus Admiral Homes Affinity Sutton Homes Alliance Planning AMEC Environment & Infrastructure UK Limited Annington Developments Ltd Appledore Developments Ltd Artesian Asprey Homes Axes Lane Banner Homes Barton Willmore Planning Partnership Batcheller Monkhouse Baxter Phillips Bell Cornwell Bellway Homes Ltd Bellway Homes Ltd, Thames Gateway South Division Berkeley Homes (South East London) Berwood Homes Bidwells LLP Bioscan (UK) Ltd BNP Paribas Real Estate Boyer Planning Limited bptw Partnership BRE Brian Barber Associates British Land Company PLC Broadlands Planning Broadway Malyan Planning Burnett Planning & Development Limited Cala Homes Calfordseaden LLP Capita Symonds Castlefort Properties Ltd Cathedral Group CBRE Ltd CgMs Consulting Chart Plan (2004) Limited Chase & Partners Clifford Rance Associates Cluttons LLP Colliers International Conrad Phoenix Properties Ltd Correct as of 21/07/2016 Conrad Ritblat Erdman Co-Operative Group Ltd., Countryside Strategic Projects plc Cranbrook Home Extensions Crest Nicholson Eastern Crest Strategic Projectsl Ltd Croudace D & M Planning Daniel Watney LLP Deloitte Real Estate DHA Planning Direct Build Services Limited DLA Town Planning Ltd dp9 DPDS Consulting Group Drivers Jonas Deloitte Dron & Wright DTZ Edwards Covell Architecture & Planning Fairclough Homes Fairview Estates (Housing) Ltd Firstplan FirstPlus Planning Limited -

CHANGING LANDSCAPES REPORT to SOCIETY 2005 Tarmac Artwork2.Qxd 24/2/06 3:28 Pm Page 2

Tarmac artwork2.qxd 24/2/06 3:28 pm Page 1 ® CHANGING LANDSCAPES REPORT TO SOCIETY 2005 Tarmac artwork2.qxd 24/2/06 3:28 pm Page 2 BIODIVERSITY HEALTH & SAFETY WATER USE COMMUNITY & EDUCATION CASE REPORT 1 04 - 05 CASE REPORT 2 06 - 07 CASE REPORT 3 08 - 09 CASE REPORT 4 10 - 11 A look at some of the In 2005 Tarmac invested Our new ‘reservoir Tarmac’s Millennium many ways in which we heavily in new equipment pavement’ technology – Eco-Centre near Wrexham are helping to encourage and devised innovative ways Tarmac Aquifa™ – is set to is helping to promote biodiversity and restore of working to ensure that reduce the risk and costs of sustainable living and natural habitats across hand arm vibration doesn’t flash flooding through its raise awareness of the UK. compromise the health of environmentally friendly environmental issues across our workforce. drainage system. the wider community. Tarmac artwork2.qxd 24/2/06 3:28 pm Page 3 CONTENTS WELCOME TO TARMAC’S REPORT TO SOCIETY FOR 2005. AS A BUSINESS, WE INTRODUCTION 01 PLAY AN ESSENTIAL ROLE IN PROVIDING ABOUT TARMAC 02 - 03 SOCIETY WITH THE RAW CONSTRUCTION CASE REPORT 1 04 - 05 MATERIALS WHICH MAKE UP THE FABRIC CASE REPORT 2 06 - 07 OF OUR DAILY LIVES. CASE REPORT 3 08 - 09 CASE REPORT 4 10 - 11 As well as our commercial considerations, we are guided by a strong sense of responsibility for the health and safety of our SAFETY 12 - 14 employees, for the environment and for the communities we HEALTH 15 - 16 work in and society as a whole. -

Guide to The

Guide to the St. Martin WWI Photographic Negative Collection 1914-1918 7.2 linear feet Accession Number: 66-98 Collection Number: FW66-98 Arranged by Jack McCracken, Ken Rice, and Cam McGill Described by Paul A. Oelkrug July 2004 Citation: The St. Martin WWI Photographic Negative Collection, FW66-98, Box number, Photograph number, History of Aviation Collection, Special Collections Department, McDermott Library, The University of Texas at Dallas. Special Collections Department McDermott Library, The University of Texas at Dallas Revised 8/20/04 Table of Contents Additional Sources ...................................................................................................... 3 Series Description ....................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ...................................................................................................... 4 Provenance Statement ................................................................................................. 4 Literary Rights Statement ........................................................................................... 4 Note to the Researcher ................................................................................................ 4 Container list ............................................................................................................... 5 2 Additional Sources Ed Ferko World War I Collection, George Williams WWI Aviation Archives, The History of Aviation Collection, -

Martlesham Heath Area Specific Guidance June 2001

Supplementary Planning Guidance 12.8 Hi-Tech Cluster: Martlesham Heath Area Specific Guidance June 2001 Following the reforms to the Planning system through the enactment of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 all Supplementary Planning Guidance’s can only be kept for a maximum of three years. It is the District Council’s intention to review each Supplementary Planning Guidance in this time and reproduce these publications as Supplementary Planning Documents which will support the policies to be found in the Local Development Framework which is to replace the existing Suffolk Coastal Local Plan First Alteration, February 2001. Some Supplementary Planning Guidance dates back to the early 1990’s and may no longer be appropriate as the site or issue may have been resolved so these documents will be phased out of the production and will not support the Local Development Framework. Those to be kept will be reviewed and republished in accordance with new guidelines for public consultation. A list of those to be kept can be found in the Suffolk Coastal Local Development Scheme December 2004. Please be aware when reading this guidance that some of the Government organisations referred to no longer exist or do so under a different name. For example MAFF (Ministry for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food) is no longer in operation but all responsibilities and duties are now dealt with by DEFRA (Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs). Another example may be the DETR (Department of Environment, Transport and Regions) whose responsibilities are now dealt with in part by the DCLG (Department of Communities & Local Government). -

Cement in 1994, 1.3 Million Tons Was 1.17 Million Tons Or 10% of the Total

CEMENT By Cheryl Solomon The industry's main product, portland California, Southern.—All other counties production, excluding Puerto Rico, increased by cement, makes up 95% of the total domestic in California. 5% to 74.3 million metric tons. production. The remainder comes from Chicago, Metropolitan.—The Illinois The industry operated 118 plants, including masonry, hydraulic, and aluminous cements. counties of Cook, DuPage, Kane, Kendall, 8 grinding facilities, to produce various types of In 1994, U.S. demand for cement increased Lake, McHenry, and Will. finished hydraulic cement. by approximately 7%. Domestic production of Illinois.—All other counties in Illinois. The size of individual companies, as a portland cement increased by 5%. Cement New York, Western.—All counties west of percentage of total U.S. finished cement imported for consumption increased to 11.3 a dividing line following the eastern boundaries production capacity, ranged from 0.4% to million metric tons. Portland cement values of Broome, Chenango, Lewis, Madison, 12.7%. The top 10 producing companies, in increased to approximately $61 per metric ton. Oneida, and St. Lawrence Counties. declining order of production, were Holnam New York, Eastern.—All counties east of Inc.; Lafarge Corp.; Essroc Materials, Inc., Legislation and Government Programs the aforementioned dividing line, except Southdown Inc.; Ash Grove Cement Co.; Blue At the beginning of the year, the Metropolitan New York. Circle Inc.; Lone Star Industries, Inc.; Lehigh Environmental Protection Agency announced New York, Metropolitan.—The five counties Portland Cement Co.; California Portland; and the availability of the agency's Report to of New York City (Bronx, Kings, New York, RC Cement Co., Inc. -

2019/3 Minutes of the Development Plans

Draft until signed MINUTES OF THE DEVELOPMENT PLANS COMMITTEE OF MARTLESHAM PARISH COUNCIL HELD ON 13 FEBRUARY 2019 Present: Mr L Brome (Committee), Mr S Denton (Chairman), Ms Drummond (Committee), Mr J Forbes (Committee), Mr Irwin (ex officio), Mr Kelso (Committee), Mr E Thompson (Committee). There were 2 members of the public. In attendance: Mrs S Robertson (Clerk) and Mrs D Linsley (Deputy Clerk). 1. Apologies: Miss J Bear, Mr C Blundell, Mr Calver, Mr W Welch. 2. Interests 2.1 Disclosable Pecuniary Interest (DPI): None declared. 2.2 Local non-Pecuniary Interest (LNPI): Mr Kelso – agenda item 7.1 Suffolk Coastal Final Draft Local Plan. Mr Kelso is the District Council ward member for Martlesham. 3. Actions from last Meeting Ongoing or on agenda 4. PUBLIC FORUM: To allow members of the public to address business on the agenda; to note any issues raised by the public Both members of the public objected to the planning application for Springfield Lodge. They had already submitted their objections to the District Council. They objected to the application on the grounds that the proposed development is overdeveloped and access to the site is dangerously close to the junction with School Lane. The development is also near the Red Lion cottages which are Grade II listed buildings. They were seeking clarification on the ownership of the right of way across the land. A previous application to develop the site more than 20 years ago had been refused by the District Council. The owner of the site had cleared the site of trees, moved earth towards Main Road and had recently put in drainage. -

Martlesham Heath - an Unorthodox Development

Home About FAQs Documents History Contact SSSI Martlesham Heath - An Unorthodox Development Over the last three decades much has been written about Martlesham Heath and the unorthodox approach taken in its development. A Revolt Against Convention A new development, rather than the spoliation of existing village communities, seemed a possible way of breaking out from the orthodoxy of the now traditional housing estate... A Village of Vision? The qualities of a village are notoriously hard to define. The only certainty is that the physical and social mesh of the village, that most subtle thing, is slow to evolve, slower still to dissolve... The Garden City: Past, Present and Future Just a few other precedents exist of private villages on green field sites. The design and layout of all these schemes has stuck closely to the standard formula favoured by the volume builders, based on discrete clusters of houses along loops or culs-de-sac, to maximise marketability and minimise capital locked up in the ground... History of The Bradford Property Trust Limited 1928-1978 The largest of the wartime purchases, the 7,420 acre Brightwell estate near Ipswich Suffolk, formed the basis of a thirty five year project that is only now (1978) coming to fruition. Brightwell included freehold rights to the Royal Air Force airfield at Martlesham... The Culpin Partnership Typical housing projects include: Master plan and some neighbourhood areas in the new village at Martlesham Heath... The Bidwell Dynasty Since 1840 surveying firm Bidwells has been quietly building a reputation in East Anglia... Urban Regeneration - The Importance of Place Making Fifty years on, they are not gated worlds, they are enclaves, (middle class ghettos maybe), of owners bonded together by a compulsory management company. -

Building Progress Together

Grafton Group plc Grafton Group Annual Report and Accounts 2020 Building Progress Together Grafton Group plc Annual Report and Accounts 2020 Introduction Building Progress Together Our Business Operating Safely During We demonstrated the strength and resilience Covid-19 of our organisation by responding to the Health and safety is a fundamental priority. challenges of 2020 while continuing to Our branches, stores and manufacturing locations evolve our business and strategy. continue to operate to the highest health and safety standards in line with Covid-19 guidance. More information on page 30 More information on page 29 1 In This Report Overview Grafton Group plc is an 2020 Highlights 2 At a Glance 4 international distributor of Our Top Brands 6 Our Story 8 building materials to trade Our Purpose and Values 10 Investment Case 12 customers and has leading Sustainability Summary 14 Stakeholder Engagement 16 positions in its markets in the Strategic Report UK, Ireland and the Netherlands. Chairman’s Statement 20 Business Model 24 Grafton is also the market Our Strategy 26 Chief Executive Officer’s Review 30 leader in the DIY, Home and Key Performance Indicators 34 Sectoral and Strategic Review 38 Garden market in Ireland and is – Distribution 38 – Retail 48 the largest manufacturer of dry – Manufacturing 50 Financial Review 52 mortar in the UK. Risk Management 56 Sustainability 66 Corporate Governance Board of Directors and Secretary 78 Directors’ Report on Corporate Governance 80 Audit and Risk Committee Report 88 Nomination Committee