A Market for Dead Things: the Gujari Bazaar and the Politics Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fish Diversity of the Vatrak Stream, Sabarmati River System, Rajasthan

Rec. zool. Surv. India: Vol. 117(3)/ 214-220, 2017 ISSN (Online) : (Applied for) DOI: 10.26515/rzsi/v117/i3/2017/120965 ISSN (Print) : 0375-1511 Fish diversity of the Vatrak stream, Sabarmati River system, Rajasthan Harinder Singh Banyal* and Sanjeev Kumar Desert Regional Centre, Zoological Survey of India, Jodhpur – 342005, Rajasthan, India; [email protected] Abstract Five species of fishes belonging to order cypriniformes from Vatrak stream of Rajasthan has been described. Taxonomic detailsKeywords along: with ecology of the fish fauna and stream morphology are also discussed. Diversity, Fish, Rajasthan, stream morphology, Vatrak Introduction Sei joins from right. Sabarmati River originates from Aravalli hills near village Tepur in Udaipur district of Rajasthan, the biggest state in India is well known for its Rajasthan and flows for 371 km before finally merging diverse topography. The state of Rajasthan can be divided with the Arabian Sea. Thus the Basin of Sabarmati River into the following geographical regions viz.: western and encompasses states of Rajasthan and Gujarat covering north western region, well known for the Thar Desert; the an area of 21,674 Sq.km between 70°58’ to 73°51’ East eastern region famous for the Aravalli hills, whereas, the longitudes and 22°15’ to 24°47’ North latitudes. The southern part of the state with its stony landscape offers Vatrak stream basin is circumscribed by Aravalli hills typical sites for water resource development where most on the north and north-east, Rann of Kachchh on the of the man-made reservoirs are present. Mahi River basin west and Gulf of Khambhat on the south. -

Charge Sheet

1 CHARGE SHEET Police station Naroda Dist Ahmedabad Charge sheet No 295/08 Date 11.12.08 Name, address & occupation of complainant / informer Shri VK Solanki Service Naroda police station Ahmedabad city. First information report no I CR No 100/02 / Date 28-2-02. Name address of Name address of Property (including Name and address of Charge or accused sent for trial accused not sent up weapons) found with witness. information name in custody on bail. for trial whether particulars of where, of offence & address and not when by & by whom circumstance addressed found & whether connected with it, including forwarded to Magistrate. in concise detail & absconders under what section (show absconder in of law charged. red ink). 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 1. Ashok Died Accused: --------- Nil-------- 1.Complainant him Offence : u/s Uttamchand Korani 1. Gulabbhai self. 143,147,148,149, (Sindhi), Age 43 Kalubhai Vanjhara, 2. Complainant Shri 302,332,323,395, years, Re. Janta Age 19 years, Re. Mahemudbhai 396, 397,398, 435, Nagar Society, Nr. Krushnanagar, Abbasbhai Bagdadi 436, 427, 376, 120 Apnaghar Society, Bhagirath resi at Chetandas’s B, 186,188, 153(A) 2 Naroda Bungalo’s, chali beside ST (1) (A) (B) and part 2. Vijaykumar Thakkarnagar, workshop Naroda 2 of 153 (A) (1) of Takhubhai Parmar, Naroda Patiya, Ahmedabad. IPC and U/s 135 (1) Age. 25 years, Ahmedabad, died in (Naroda I 111/02). of BP Act, in such Re.Mahajaniyawas, police firing in mob 3. Complainant Shri a way that, as the Jatubhai Chapra, at Naroda Patiya. Sumarmiyan incident of burning Saijpur Patiya, Muhammadmiyan alive 58 (Hindu) Naroda 2. -

Disastrous Condition of the Sabarmati River

PRESS RELEASE 27 March 2019 Disastrous Condition of the Sabarmati River - Release of report on joint investigations by Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti and Gujarat Pollution Control Board, of the pollution levels in the prime water source of Ahmedabad District. The Sabarmati River in the Ahmedabad City stretch, before the Riverfront, is dry and within the Riverfront Project stretch, is Brimming with Stagnant Water. In the last 120 kilometres, before meeting the Arabian Sea, it dead comprises of just industrial effluent and sewage. On 12 March 2019, the Regional Officers Mr Tushar Shah and Ms Nehalben Ajmera of Gujarat Pollution Control Board, Rohit Prajapati and Krishnakant of Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti, Social Activist Mudita Vidrohi of Ahmedabad, Subodh Parmar, Lawyer of Gujarat High Court, conducted a joint investigation. This was conducted in the context of implementation of the Order, dated 22.02.2017, of the Supreme Court in Writ Petition (Civil) No. 375 of 2012 (Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti & Anr V/s Union of India & Ors) about the status of industrial effluent and sewerage discharge into the Sabarmati River stretch of Ahmedabad District. The investigation reports are shocking and reveal the disastrous condition of Sabarmati River in and around Ahmedabad District and about 120 kilometres downstream. Sabarmati River no longer has any fresh water when it enters the city of Ahmedabad. The Sabarmati Riverfront has merely become a pool of polluted stagnant water while the river, downstream of the riverfront, has been reduced to a channel carrying effluents from industries from Naroda, Odhav Vatva, Narol and sewerage from Ahmedabad city. The drought like condition of the Sabarmati River intensified by the Riverfront Development has resulted in poor groundwater recharge and increased dependency on the already ailing Narmada River. -

87 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

87 bus time schedule & line map 87 Kalupur Terminus - Chandkheda View In Website Mode The 87 bus line (Kalupur Terminus - Chandkheda) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chandkheda: 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM (2) Kalupur Terminus: 7:50 AM - 10:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 87 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 87 bus arriving. Direction: Chandkheda 87 bus Time Schedule 26 stops Chandkheda Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Monday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Maninagar Maninagar Railway Station, Ahmadābād Tuesday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Jawahar Chowk Wednesday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Bhairavnath Thursday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Friday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Sah Alam Darwaja Saturday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM S. T. Stand Kamnath Mahadev / Raipur Darwaja Sarangpur 87 bus Info Direction: Chandkheda Kalupur Stops: 26 Trip Duration: 47 min Naroda Road, Ahmadābād Line Summary: Maninagar, Jawahar Chowk, Prem Darwaja Bhairavnath, Sah Alam Darwaja, S. T. Stand, Kamnath Mahadev / Raipur Darwaja, Sarangpur, Kalupur, Prem Darwaja, Dariyapur Darwaja, Delhi Dariyapur Darwaja Darwaja, Income Tax O∆ce, Usmanpura, Vadaj Bus Terminuss, Subhash Bridge, Keshav Nagar, Delhi Darwaja Dharmanagar, Ram Nagar, Chintamani Society, Abu Koba Cross Road, Gujarat Stadium, Motera Gam, Income Tax O∆ce Government Engineering College, Santokba Hospital, Shivshakti Nagar, Chandkheda Usmanpura Vadaj Bus Terminuss Subhash Bridge Keshav Nagar Dharmanagar Ram Nagar Chintamani Society Abu Koba Cross Road Ram Bag Road, Ahmadābād Gujarat Stadium -

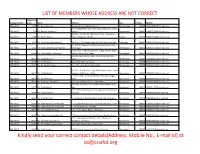

Kindly Send Your Correct Contact Details(Address, Mobile No., E-Mail Id) at [email protected] LIST of MEMBERS WHOSE ADDRESS ARE NOT CORRECT

LIST OF MEMBERS WHOSE ADDRESS ARE NOT CORRECT Membersh Category Name ip No. Name Address City PinCode EMailID IND_HOLD 6454 Mr. Desai Shamik S shivalik ,plot No 460/2 Sector 3 'c' Gandhi Nagar 382006 [email protected] Aa - 33 Shanti Nath Apartment Opp Vejalpur Bus Stand IND_HOLD 7258 Mr. Nevrikar Mahesh V Vejalpur Ahmedabad 380051 [email protected] Alomoni , Plot No. 69 , Nabatirtha , Post - Hridaypur , IND_HOLD 9248 Mr. Halder Ashim Dist - 24 Parganas ( North ) Jhabrera 743204 [email protected] IND_HOLD 10124 Mr. Lalwani Rajendra Harimal Room No 2 Old Sindhu Nagar B/h Sant Prabhoram Hall Bhavnagar 364002 [email protected] B-1 Maruti Complex Nr Subhash Chowk Gurukul Road IND_HOLD 52747 Mr. Kalaria Bharatkumar Popatlal Memnagar Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] F/ 36 Tarun - Nagar Society Part - 2 Opp Vishram Nagar IND_HOLD 66693 Mr. Vyas Mukesh Indravadan Gurukul Road, Mem Nagar, Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] 8, Keshav Kunj Society, Opp. Amar Shopping Centre, IND_HOLD 80951 Mr. Khant Shankar V Vatva, Ahmedabad 382440 [email protected] IND_HOLD 83616 Mr. Shah Biren A 114, Akash Rath, C.g. Road, Ahmedabad 380006 [email protected] IND_HOLD 84519 Ms. Deshpande Yogita A - 2 / 19 , Arvachin Society , Bopal Ahmedabad 380058 [email protected] H / B / 1 , Swastick Flat , Opp. Bhawna Apartment , Near IND_HOLD 85913 Mr. Parikh Divyesh Narayana Nagar Road , Paldi Ahmedabad 380007 [email protected] 9 , Pintoo Flats , Shrinivas Society , Near Ashok Nagar , IND_HOLD 86878 Ms. Shah Bhavana Paldi Ahmedabad 380006 [email protected] IND_HOLD 89412 Mr. Shah Rajiv Ashokbhai 119 , Sun Ville Row Houses , Mem Nagar , Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] B4 Swetal Park Opp Gokul Rowhouse B/h Manezbaug IND_HOLD 91179 Mr. -

INTRODUCTION Water Is Super Abundant on the Planet As a Whole

INTRODUCTION Water is super abundant on the planet as a whole, but fresh potable water is not always available for human or ecosystem use. The importance of water is underscored by the fact that many great civilizations in the past sprang up along or near water bodies and most developmental activities are still dependent upon them. The development of water resources has often been used as yardstick for socioeconomic and health status of many nations worldwide. However, pollution of water often been neglected the benefits obtained from the development of these water resources. Rivers have always been the most important fresh water resources; river water finds multiple uses in every sector of development like agriculture, industry, transportation, aquaculture, public water supply etc. but surface waters are most exposable to pollution due to their accessibility for disposal of wastewaters. Huge loads of waste from industries, domestic sewage & agricultural practices find their way into rivers, resulting in large scale deterioration of the water quality. The Sabarmati River arises in the Aravalli Hills, which roughly mark the Western boundary of Udaipur District, i.e. Mount Abu area, and flows in a South-Westerly direction. It is approximately 371 km in length. The main tributaries of the Sabarmati River are Wakal, the Harnay, the Hathimati, the Vatrak, the Meshwa & the Sei Nadi, which also flow South- Westwards in courses generally parallel to the Sabarmati River, up to their confluence with the river (in Gujarat). And finally it empties in the Gulf of Cambay of Arabian Sea. The Sabarmati River Basin is situated in the mid-Sothern part of Rajasthan, between latitudes 23025’ & 24055’ and longitudes 73000’ & 73048’. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

The Spectre of SARS-Cov-2 in the Ambient Urban Natural Water in Ahmedabad and Guwahati: a Tale of Two Cities

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.12.21258829; this version posted June 16, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . The Spectre of SARS-CoV-2 in the Ambient Urban Natural Water in Ahmedabad and Guwahati: A Tale of Two Cities Manish Kumar1,2*, Payal Mazumder3, Jyoti Prakash Deka4, Vaibhav Srivastava1, Chandan Mahanta5, Ritusmita Goswami6, Shilangi Gupta7, Madhvi Joshi7, AL. Ramanathan8 1Discipline of Earth Science, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382 355, India 2Kiran C Patel Centre for Sustainable Development, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India 3Centre for the Environment, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Assam 781039, India 4Discipline of Environmental Sciences, Gauhati Commerce College, Guwahati, Assam 781021, India 5Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Assam 781039, India 6Tata Institute of Social Science, Guwahati, Assam 781012, India 7Gujarat Biotechnology Research Centre (GBRC), Sector- 11, Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382 011, India 8School of Environmental Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi 110067, India *Corresponding Author: [email protected]; [email protected] Manish Kumar | Ph.D, FRSC, JSPS, WARI+91 863-814-7602 | Discipline of Earth Science | IIT Gandhinagar | India 1 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.12.21258829; this version posted June 16, 2021. -

Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation Councillor List (Term 2021-2026)

Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation Councillor List (term 2021-2026) Ward No. Sr. Mu. Councillor Address Mobile No. Name No. 1 1-Gota ARATIBEN KAMLESHBHAI CHAVDA 266, SHIVNAGAR (SHIV PARK) , 7990933048 VASANTNAGAR TOWNSHIP, GOTA, AHMEDABAD‐380060 2 PARULBEN ARVINDBHAI PATEL 291/1, PATEL VAS, GOTA VILLAGE, 7819870501 AHMEDABAD‐382481 3 KETANKUMAR BABULAL PATEL B‐14, DEV BHUMI APPARTMENT, 9924136339 SATTADHAR CROSS ROAD, SOLA ROAD, GHATLODIA, AHMEDABAD‐380061 4 AJAY SHAMBHUBHAI DESAI 15, SARASVATINAGAR, OPP. JANTA 9825020193 NAGAR, GHATLODIA, AHMEDABAD‐ 380061 5 2-Chandlodia RAJESHRIBEN BHAVESHBHAI PATEL H/14, SHAYONA CITY PART‐4, NR. R.C. 9687250254, 8487832057 TECHNICAL ROAD, CHANDLODIA‐ GHATLODIA, AHMDABAD‐380061 6 RAJESHWARIBEN RAMESHKUMAR 54, VINAYAK PARK, NR. TIRUPATI 7819870503, PANCHAL SCHOOL, CHANDLODIA, AHMEDABAD‐ 9327909986 382481 7 HIRABHAI VALABHAI PARMAR 2, PICKERS KARKHANA ,NR. 9106598270, CHAMUDNAGAR,CHANDLODIYA,AHME 9913424915 DABAD‐382481 8 BHARATBHAI KESHAVLAL PATEL A‐46, UMABHAVANI SOCIETY, TRAGAD 7819870505 ROAD, TRAGAD GAM, AHMEDABAD‐ 382470 9 3- PRATIMA BHANUPRASAD SAXENA BUNGLOW NO. 320/1900, Vacant due to Chandkheda SUBHASNAGAR, GUJ. HO.BOARD, resignation of Muni. CHANDKHEDA, AHMEDABAD‐382424 Councillor 10 RAJSHRI VIJAYKUMAR KESARI 2,SHYAM BANGLOWS‐1,I.O.C. ROAD, 7567300538 CHANDKHEDA, AHEMDABAD‐382424 11 RAKESHKUMAR ARVINDLAL 20, AUTAMNAGAR SOC., NR. D CABIN 9898142523 BRAHMBHATT FATAK, D CABIN SABARMATI, AHMEDABAD‐380019 12 ARUNSINGH RAMNYANSINGH A‐27,GOPAL NAGAR , CHANDKHEDA, 9328784511 RAJPUT AHEMDABAD‐382424 E:\BOARDDATA\2021‐2026\WEBSITE UPDATE INFORMATION\MUNICIPAL COUNCILLOR LIST IN ENGLISH 2021‐2026 TERM.DOC [ 1 ] Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation Councillor List (term 2021-2026) Ward No. Sr. Mu. Councillor Address Mobile No. Name No. 13 4-Sabarmati ANJUBEN ALPESHKUMAR SHAH C/O. BABULAL JAVANMAL SHAH , 88/A 079- 27500176, SHASHVAT MAHALAXMI SOCIETY, RAMNAGAR, SABARMATI, 9023481708 AHMEDABAD‐380005 14 HIRAL BHARATBHAI BHAVSAR C‐202, SANGATH‐2, NR. -

Floating Restaurant at Sabarmati Riverfront

Development of Floating restaurant at Sabarmati riverfront Tourism Government of Gujarat Contents Project Concept 3 Market Potential 4 Growth Drivers 5 Gujarat – Competitive Advantage 6 Project Information 8 - Location/ Size - Key Players/ Machinery Suppliers - Infrastructure Availability/ Connectivity - Raw Material/ Manpower - Key Considerations Project Financials 13 Approvals & Incentives 14 Key Department Contacts 15 Page 2 Project Concept About riverside floating restaurant A riverside restaurant or a floating restaurant is usually a restaurant built on a large flat steel barge floating on water. Some times retired ships are also refurbished and given a second term as a floating restaurant. Some of the floating restaurants in India are- 1. Majastique-1 operated by Majas Travels, Tours and Logistics at Kochi 2. Flor Do Mar operated at Morjim Beach, Goa A revolving restaurant or rotating restaurant on the other hand is usually a tower based restaurant eating space designed to rest on the top of a wide spherical rotating base that operates as a large turning table. The building remains stationary and the diners are seated on the revolving floor with all the other basic restaurant features in place. The main aim of such restaurant is to provide a scenic view to its diners from a height. About Sabarmati riverfront Sabarmati river has been an essential component in of daily life in Ahmedabad since when the city was established in 1411 along the river side. Apart from being an essential source of water, it provides a view of cultural activities and historic significance of various events. During the dry seasons, the fertile river side became a good farming land. -

Digital Issue 400.00 `

62 2020 lajournal.in ISSN 0975-0177 | cklB DIGITAL ISSUE 400.00 ` landscape 1 62 | 2020 INSTALLINGINSTALLING TWO-WIRE TWO-WIRE INSTALLINGJustJust Got Got aTWO-WIRE Lot a LotEasier Easier INSTALLINGJust Got a Lot TWO-WIRE Easier Just Got a Lot Easier INSTALLING TWO-WIRE Just Got a Lot Easier With the revolutionary EZ Decoder System, you get all the advantages of two-wire installations with simpler, more cost-effectiveWith the technology.revolutionary Plug EZ in theDecoder EZ-DM System, two-wire you output get allmodule the advantagesto enable up ofto two-wire54 stations installations of with simpler, you get all the advantages of two-wire installations with simpler, Withirrigation,With the the revolutionary revolutionary plusmore a master cost-effective valve,EZ EZ Decoder Decoder on atechnology. single System, System, pair of Plugwires. you in get the allEZ-DM the advantages two-wire output of two-wire module installations to enable up with to 54 simpler, stations of Withmore the cost-effective revolutionaryirrigation, technology. plusEZ Decoder a master System,Plug valve, in the you on EZ-DMget a singleall thetwo-wire advantagespair of output wires. of two-wiremodule toinstallations enable up with to 54simpler, stations of moremoreirrigation, cost-effective cost-effective plus a master technology. technology. valve, onPlug a insinglePlug the in EZ-DMpair the of two-wirewires.EZ-DM two-wireoutput module output to enable module up to to54 enablestations upof to 54 stations of irrigation,irrigation, plusplus a amaster master valve, valve, -

Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project

SABARMATI RIVERFRONT DEVELOPMENT PROJECT A Multidimensional Environmental Improvement and Urban Rejuvenation Project … one of the most innovative projects towards urban regeneration in the world to make the city livable & sustainable (KPMG ) SABARMATI RIVER and AHMEDABAD The River Sabarmati flows from north to south splitting Ahmedabad into almost two equal parts. For many years, it has served as a water source and provided almost no formal recreational space for the city. As the city has grown, the Sabarmati river had been abused and neglected and with the increased pollution was posing a major health and environmental hazard to the city. The slums on the riverbank were disastrously flood prone and lack basic infrastructure services. The River became back of the City and inaccessible to the public Ahmedabad and the Sabarmati :1672 Sabarmati and the Growth of Ahmedabad Sabarmati has always been important to Ahmedabad As a source for drinking water As a place for recreation As a place to gather Place for the poor to build their hutments Place for washing and drying clothes Place for holding the traditional Market And yet, Sabarmati was abused and neglected Sabarmati became a place Abuse of the River to dump garbage • Due to increase in urban pressures, carrying capacity of existing sewage system falling short and its diversion into storm water system releasing sewage into the River. Storm water drains spewed untreated sewage into the river • Illegal sewage connections in the storm water drains • Open defecation from the near by human settlements spread over the entire length. • Discharge of industrial effluent through Nallas brought sewage into some SWDs.