A Last Fling in Local Distinctiveness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bury St Edmunds

THE BURY ST EDMUNDS IP31 2PJ TBS YARD - GREATBARTON MOT Prep Exhausts Servicing Brakes Battries Tyres - Repars Open 7 Days a Week Issue 41 November 2020 Delivered from 26/10/20 Monday - Friday 8am - 17.30 Saturday 8am - 4pm Also covering - Horringer Westley - The Fornhams - Great Barton Sundays by Appointmnet only AAdvertisingdvertising SSales:ales: 0012841284 559292 449191 wwww.flww.fl yyeronline.co.ukeronline.co.uk The Flyer #YourFuture #YourSay - West Suffolk Local Plan at open all hours exhibition A virtual exhibition at a village hall space, or over the phone on 01284 that is open all hours is part of new 757368. initiatives designed to put residents at the heart of forming a new Local Plan The Local Plan helps local communities for West Suffolk. continue to thrive in the future by setting out where homes will be built A new 10 week consultation has and supports, with other Council been launched this week on the policies) where new jobs and other Local Plan which will help shape the vital facilities are located. All West future of communities and supporting Suffolk planning decisions are judged development up to 2040. against Local Plan policies. and Options which will started on 13 and seeking comments on a variety October and will last for 10 weeks. of issues and options. This includes West Suffolk Council are now asking The Local Plan ensures the right questions such as have we identifi ed people to have their say on the initial number and types of homes are built This initial stage which will help shape the challenges correctly, and relevant Issues and Options phase which sets in the right places and through its the plan and the future of West Suffolk local issues, as well whether we have the foundations of the formation of policies supports the provision of as it develops. -

Classes and Activities in the Mid Suffolk Area

Classes and activities in the Mid Suffolk area Specific Activities for Cardiac Clients Cardiac Exercise 4 - 6 Professional cardiac and exercise support set up by ex-cardiac patients. Mixture of aerobics, chair exercises and circuits. Education and social. Families and carers welcome. Mid Suffolk Leisure Centre, Stowmarket, IP14 1LH on Monday 2-3pm, Wednesday 2.30pm-3.30pm and Friday 10.45 – 11.45am. Bob Halls 01449 674980 or 07754 522233 Red House (Old Library), Stowmarket, IP14 1BE on Friday 1.30-2.30pm. Maureen Cooling 01787 211822 3 27/02/2017 General Activities Suitable for all Clients Aqua Fit 4-6 A fun and invigorating all over body workout in the water designed to effectively burn calories with minimal impact on the body. Great for those who are new or returning to exercise. Mid Suffolk Leisure Centre, Stowmarket, IP14 1LH on Monday 2-3pm (50+), Tuesday 1-2pm and Thursday 9.10 - 9.55pm. Becky Cruickshank 01449 674980 Stradbroke Leisure Centre, IP21 5JN on Monday 12pm-12.45pm, Tuesday 1.45- 2.30pm, Thursday 11- 11.45 and 6.30-7.30pm. Stuart Murdy 01379384376. Balance Class 3 Help with posture and stability. Red Gables Community Centre, Stowmarket, IP14 1BE on Mondays (1st, 2nd and 4th) at 10.15-11am. Lindsay Bennett 01473 345350 Body Balance 4-6 BODYBALANCE™ is the Yoga, Tai Chi, Pilates workout that builds flexibility and strength and leaves you feeling centred and calm. Controlled breathing, concentration and a carefully structured series of stretches, moves and poses to music create a holistic workout that brings the body into a state of harmony and balance. -

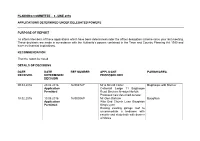

Planning Committee

PLANNING COMMITTEE - APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 28.03.2017 23.05.2017 17/00605/F Mr & Mrs P Carter Barton Bendish Application Victory Lodge Eastmoor Road Refused Eastmoor Barton Bendish REMOVAL OF CONDITION 2 OF PLANNING PERMISSION 2/89/4593/F: Construction of dwellinghouse, garage and grandad annexe 31.03.2017 26.05.2017 17/00633/F Mr Stephen Tighe Barton Bendish Application Keepers Cottage 29 Church Lane Permitted Barton Bendish King's Lynn Variation of Condition 2 attached to planning permission 16/01372/F to allow an increase in the ridge height and the addition of two rooflights 24.05.2017 14.06.2017 16/01719/NMA_1 Mr And Mrs David Hess Burnham Overy Application Hancocks Barn Church Hill Farm Permitted Barns Wells Road Burnham Overy Town Non-material amendment to planning permission 16/01719/F: Extending existing garage to create new kitchen, adding two roof lights to existing roof & rationalising existing roof lights to rear 17.02.2017 14.06.2017 17/00298/F Mr P Bateman Brancaster Application The Police House Main Road Permitted Brancaster King's Lynn Demolition of dwelling -

SEBC Planning Applications 30/18

LIST 30 27 July 2018 Applications Registered between 23.07.2018 – 27.07.2018 ST EDMUNDSBURY BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED The following applications for Planning Permission, Listed Building, Conservation Area and Advertisement Consent and relating to Tree Preservation Orders and Trees in Conservation Areas have been made to this Council. A copy of the applications and plans accompanying them may be inspected during normal office hours on our website www.westsuffolk.gov.uk Representation should be made in writing, quoting the reference number and emailed to [email protected] to arrive not later than 21 days from the date of this list. Application No. Proposal Location DC/18/1261/HH Householder Planning Application - (i) single Lavender Barn VALID DATE: storey rear extension to dwelling (ii) single Low Street 23.07.2018 storey rear extension to garage with velux Bardwell windows IP31 1AR EXPIRY DATE: 17.09.2018 APPLICANT: Mr Gordon Mc Meechan AGENT: Mr Mark Lewis - MNL Designs Ltd GRID REF: WARD: Bardwell 594207 273268 CASE OFFICER: Matthew Harmsworth PARISH: Bardwell DC/18/1164/HH Householder Planning Application - 63 Kings Road VALID DATE: Replacement of front door Bury St Edmunds 18.07.2018 IP33 3DR APPLICANT: Mr Timothy Glover EXPIRY DATE: 12.09.2018 GRID REF: CASE OFFICER: Debbie Cooper 584724 264116 WARD: Abbeygate PARISH: Bury St Edmunds Town Council (EMAIL) DC/18/1239/TPO TPO 178 (1974) Tree Preservation Order - 3 Hardwick Lane VALID DATE: 1no. Lime - Fell Bury St Edmunds 23.07.2018 IP33 2QF APPLICANT: Mr James Drew EXPIRY DATE: 17.09.2018 GRID REF: CASE OFFICER: Adam Yancy 585990 263107 WARD: Southgate PARISH: Bury St Edmunds Town Council (EMAIL) DC/18/1311/TPO TPO277 (1999) Tree Preservation Order - 2 Chancellery Mews VALID DATE: 3no Sycamore (T2 on plan and order) prune Bury St Edmunds 06.07.2018 back by 2. -

Suffolk. · [1\Elly's Waxed Paper Manufctrs

1420 WAX SUFFOLK. · [1\ELLY'S WAXED PAPER MANUFCTRS. Cowell J. Herringswell, Mildenhall S.O HoggerJn.ThorpeMorieux,BildestonS.O Erhardt H. & Co, 9 & 10 Bond court, Cowle Ernest, Clare R.S.O Hogger William, Bildeston S.O London E c; telegraphic address, CracknellJ.MonkSoham, Wickhm.Markt Hollmgsworth Saml. Bred field, Woodbdg "Erhardt, London" Cracknell Mrs. Lucy, Redlingfield, Eye IIowardW.Denningtn.Framlnghm.R.S.O Craske S. Rattlesden, BurySt.Edmunds Howes HaiTy, Debenham, Stonham WEIGHING MACHINE MAS. Crick A. Wickhambrook, Newmarket Hubbard Wm.llessett,BurySt.Edmunds Arm on Geo. S. 34 St.John's rd. Lowestoft Crisp Jn. RushmereSt. Andrew's, Ipswich J effriesE.Sth.ElmhamSt.George,Harlstn Cross J.6 OutN0rthgate,BurySt.Edmds Jillings Thos. Carlton Colville, Lowestft Poupard Thomas James 134 Tooley Cross Uriah, Great Cornard, Sudbury Josselyn Thomas, Belstead, Ipswich street London 8 E ' Crouchen George, Mutford, Beccles J osselyn Thomas, Wherstead, Ipswich ' Crow Edward, Somerleyton, Lowestoft Keeble Geo.jun.Easton, WickhamMarket WELL SINKERS. Cullingford Frederick, Little street, Keeble Samuel William, Nacton, Ipswich Alien Frederick Jas. Station rd. Beccles Yoxford, Saxmundham · Kendall Alfred, Tuddenham St. Mary, Chilvers William John Caxton road Culpitt John, Melton, Woodbridge Mildenhall S.O Beccles & at Wangford R.S.O ' Cur~is 0. Geo.Bedfiel~, ',"ickha~Market Kent E. Kettleburgh, Wickham Market Cornish Charles Botesdale Diss Damels Charles,Burkttt slane, ~udbury Kent John, Hoxne, Scole Prewer Jn. Hor~ingsheath; Bury St. Ed Davey Da:vi_d, Peasenhall, Saxrnund~am Kerry J~~Il:• Wattisfield, Diss Youell William Caxton road Beccles Davey "\Vllham, Swan lane, Haverh1ll Kerry\\ 1lham, Thelnetham, Thetford ' ' Davy John, Stoven, Wangford R.S.O Kerry William, Wattisfield, Diss WHABFINGERS. -

Heritage Impact Assessment for Local Plan Site Allocations Stage 1: Strategic Appraisal

Babergh & Mid Suffolk District Councils Heritage Impact Assessment for Local Plan Site Allocationsx Stage 1: strategic appraisal Final report Prepared by LUC October 2020 Babergh & Mid Suffolk District Councils Heritage Impact Assessment for Local Plan Site Allocations Stage 1: strategic appraisal Project Number 11013 Version Status Prepared Checked Approved Date 1. Draft for review R. Brady R. Brady S. Orr 05.05.2020 M. Statton R. Howarth F. Smith Nicholls 2. Final for issue R. Brady S. Orr S. Orr 06.05.2020 3. Updated version with additional sites F. Smith Nicholls R. Brady S. Orr 12.05.2020 4. Updated version - format and typographical K. Kaczor R. Brady S. Orr 13.10.2020 corrections Bristol Land Use Consultants Ltd Landscape Design Edinburgh Registered in England Strategic Planning & Assessment Glasgow Registered number 2549296 Development Planning London Registered office: Urban Design & Masterplanning Manchester 250 Waterloo Road Environmental Impact Assessment London SE1 8RD Landscape Planning & Assessment landuse.co.uk Landscape Management 100% recycled paper Ecology Historic Environment GIS & Visualisation Contents HIA Strategic Appraisal October 2020 Contents Cockfield 18 Wherstead 43 Eye 60 Chapter 1 Copdock 19 Woolverstone 45 Finningham 62 Introduction 1 Copdock and Washbrook 19 HAR / Opportunities 46 Great Bicett 62 Background 1 East Bergholt 22 Great Blakenham 63 Exclusions and Limitations 2 Elmsett 23 Great Finborough 64 Chapter 4 Sources 2 Glemsford 25 Assessment Tables: Mid Haughley 64 Document Structure 2 Great Cornard -

6 June 2016 Applications Determined Under

PLANNING COMMITTEE - 6 JUNE 2016 APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 09.03.2016 29.04.2016 16/00472/F Mr & Mrs M Carter Bagthorpe with Barmer Application Cottontail Lodge 11 Bagthorpe Permitted Road Bircham Newton Norfolk Proposed new detached garage 18.02.2016 10.05.2016 16/00304/F Mr Glen Barham Boughton Application Wits End Church Lane Boughton Permitted King's Lynn Raising existing garage roof to accommodate a bedroom with ensuite and study both with dormer windows 23.03.2016 13.05.2016 16/00590/F Mr & Mrs G Coyne Boughton Application Hall Farmhouse The Green Permitted Boughton Norfolk Amendments to extension design along with first floor window openings to rear. 11.03.2016 05.05.2016 16/00503/F Mr Scarlett Burnham Market Application Ulph Lodge 15 Ulph Place Permitted Burnham Market Norfolk Conversion of roofspace to create bedroom and showerroom 16.03.2016 13.05.2016 16/00505/F Holkham Estate Burnham Thorpe Application Agricultural Barn At Whitehall Permitted Farm Walsingham Road Burnham Thorpe Norfolk Proposed conversion of the existing barn to residential use and the modification of an existing structure to provide an outbuilding for parking and storage 04.03.2016 11.05.2016 16/00411/F Mr A Gathercole Clenchwarton Application Holly Lodge 66 Ferry Road Permitted Clenchwarton King's Lynn Proposed replacement sunlounge to existing dwelling. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Babergh Planning Committee, 06/12/2017 09:30

Public Document Pack COMMITTEE: PLANNING COMMITTEE VENUE: Hadleigh Town Hall, Market Place, Hadleigh DATE: Wednesday, 6 December 2017 9.30 am PLEASE NOTE CHANGE OF VENUE Members Sue Ayres Kathryn Grandon Simon Barrett John Hinton Peter Beer Michael Holt David Busby Adrian Osborne Luke Cresswell Stephen Plumb Derek Davis Nick Ridley Alan Ferguson Ray Smith The Council, members of the public and the press may record/film/photograph or broadcast this meeting when the public and the press are not lawfully excluded. Any member of the public who attends a meeting and objects to being filmed should advise the Committee Clerk. AGENDA PART 1 ITEM BUSINESS Page(s) 1 SUBSTITUTES AND APOLOGIES Any Member attending as an approved substitute to report giving his/her name and the name of the Member being substituted. To receive apologies for absence. 2 DECLARATION OF INTERESTS Members to declare any interests as appropriate in respect of items to be considered at this meeting. 3 TO RECEIVE NOTIFICATION OF PETITIONS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE COUNCIL'S PETITION SCHEME ITEM BUSINESS Page(s) 4 QUESTIONS BY THE PUBLIC To consider questions from, and provide answers to, the public in relation to matters which are relevant to the business of the meeting and of which due notice has been given in accordance with the Committee and Sub-Committee Procedure Rules. 5 QUESTIONS BY COUNCILLORS To consider questions from, and provide answer to, Councillors on any matter in relation to which the Committee has powers or duties and of which due notice has been given in accordance with the Committee and Sub-Committee Procedure Rules. -

Parish Mag Master

PARISH MAGAZINE Redgrave cum Botesdale and Rickinghall Village Word Search July 2012 Find the following words in the grid above Botesdale Bridewell Church Ducks Farmers Market Fen Hairdressers Hall Inferior Kitchen Manor Mid Suffolk Mobile Library Newsagents Parish Park Farm Pond Post Office Pub Redgrave Rickinghall St Botolphs Way Stream Street Superior Takeaway Tinteniac Ulfketel Village Waveney Rev’d Chris Norburn Rector of Redgrave cum Botesdale with the Rickinghalls The Rectory, Bury Road, Rickinghall, Diss. IP22 1HA Tel: 01379 898685 St Mary’s Rickinghall Inferior now has a web site http://stmarysrickinghallinferior.onesuffolk.net/ or Google: St Mary's Rickinghall Inferior When my passions rise up inside me I often find myself compelled we often call the ‘gospels’, the to speak. For me this happens when an issue close to my heart is narratives of Jesus’ life and death, being discussed by others and I feel compelled to interject. For me were only written later for the this also happens when I feel an injustice is being, or about to be benefit of those who had already perpetrated. Compulsion to speak out can be for many different accepted the gospel! They were in reasons and can sometimes take you by surprise, so there are many no sense the basis of Christianity different patterns to our compulsions to speak out. Likewise there because they were first written for are no fixed patterns for God as he speaks to us and compels us to those who had already converted to speak for him here. Christianity. The first fact in the Rev history of Christianity is that a This means that there are many different ways of bringing people number of people (Jesus’ disciples and first followers) say that they into His Kingdom. -

KING's LYNN SCHOOLS Including King Edward VII High, Springwood High, King's Lynn Academy SCHOOL Timetables from September 2014

KING'S LYNN SCHOOLS Including King Edward VII High, Springwood High, King's Lynn Academy SCHOOL Timetables from September 2014 Contractor ref: NG/25382/4 NG37 Setchey, Bridge Layby 804 1542 Setchey, Church 805 1541 Setchey, A10 Garage 806 1540 West Winch, A10 opp The Mill 810 1534 West Winch, A10 ESSO Garage 812 1532 King's Lynn Academy, Bus Loop 835 1510 Contractor ref: NG/25372/4 NG38 Blackborough End, Bus Shelter 750 1540 Middleton, School Road 752 1538 North Runcton, New Road Post Box 755 1535 West Winch, Coronation Avenue 757 1533 West Winch, Gravel Hill Lane / Oak Avenue 800 1530 West Winch, Hall Lane, junction of Eller Drive 802 1528 West Winch, Hall Lane,opp Laurel Grove 804 1526 West Winch, Back Lane / Common Close 805 1525 King's Lynn Academy, Bus Loop 820 1510 Contractor ref: NG/25371/4 NG39 West Winch, Gravel Hill Lane / Oak Avenue 803 1542 West Winch, Hall Lane,opp Eller Avenue 806 1540 West Winch, Long Lane / Hall Lane phone box 808 1538 King's Lynn Academy, Bus Loop 835 1510 Contractor ref: EG/19968/1 EG 1 Gayton Thorpe, Phone Box 805 1610 Gayton, opp The Crown 810 1605 Gayton, Lynn Road / Winch Road 816 1559 Gayton, Lynn Road / Whitehouse Service Station 818 1557 Ashwicken, B1145 / Well Hall Lane 821 1554 Ashwicken, B1145 / Pott Row Turn 823 1552 Ashwicken, B1145 / East Winch Road 825 1550 Springwood High School, Bus Loop 840 1535 Contractor ref: NG/19970/1 NG 3 Wolferton, Friar Marcus Stud 757 1609 Wolferton, Village Sign 758 1610 Sandringham, Gardens 804 1603 West Newton, Bus Shelter 807 1600 Castle Rising, Bus Stop 813 1554 North Wootton, Bus Shelter 817 1550 Springwood High School, Bus Loop 835 1535 @ CONNECTS WITH BUS TO/FROM CONGHAM Contractor ref: Flitcham, Fruit Farm 748 1624 Congham, Manor Farm 758 1614 .. -

Contact Details for the Website

1 Churches Together in Kings Lynn: Contact details for the website. www.churchestogetherkingslynn.com Churches Together in England https://www.cte.org.uk/ representative: Catherine Howe [email protected] County Ecumenical Officer for Norfolk and Waveney www.nwct.org.uk Denominational Ecumenical Minister: Revd Karlene Kerr (see St Faith’s Church entry). Andrew Frere-Smith, Development worker, Imagine Norfolk Together: Email: [email protected] Website: www.imaginenorfolktogether.org Baptist Church: Cornerstone King’s Lynn Baptist Church, Wisbech Rd., South Lynn, PE30 5JS. Pastor: Revd. Kevan Crane: The Church Office is open Monday to Friday 9am to 12.00 Noon. Community Cafe open Wed & Fridays 9am to 4pm & Thursdays 12.00 Noon to 4pm. Website: www.klbc.org.uk E-mail: [email protected]. Sunday services: 10.00am and worship, prayer and communion service on the last Sunday of the month at 6pm. All services are held in the church. Updated 28/01/20. Confidentiality agreed 15/11/17. Kings Lynn Churches Together Winter Night Shelter Charity No: 1175645. 5 St Ann's Fort, Kings Lynn, PE30 1QS. Co-ordinator: Lucy McKitterick. Tel: 01553 776109 Email: [email protected] Website: www.klwns.org.uk Donate at: https://mydonate.bt.com/charities/kingslynnwinternightshelter Christians Against Poverty (CAP) Debt Centre: Emily Hart, the Debt Centre manager: email [email protected] or ring 07495017364. Telephone: 01274 760720 Bradford head office: https://capuk.org/connect/contact-us Address: Christians Against Poverty, Jubilee Mill, North Street, Bradford, BD1 4EW New enquiries helpline: 0800 328 0006 Head office client support: 01274 761 999 or [email protected] (please include your six-digit case number in the subject line) Supporter enquiries: 01274 760 761 or [email protected] Any other enquiries: 01274 760 720 or [email protected] Updated 02/02/18. -

The King's Lynn and West Norfolk Local Plan

Examination of the King’s Lynn and West Norfolk Local Plan: Site Allocations and Development Management Policies King’s Lynn and West Norfolk Borough Council THE KING’S LYNN AND WEST NORFOLK LOCAL PLAN: SITE ALLOCATIONS AND DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT POLICIES HEARING AGENDAS FOR RESUMED HEARINGS September 2015 Clare Cobley - Programme Officer Tel 01553 616811 [email protected] 1 Examination of the King’s Lynn and West Norfolk Local Plan: Site Allocations and Development Management Policies INDEPENDENT EXAMINATION OF THE KING’S LYNN AND WEST NORFOLK LOCAL PLAN: SITE ALLOCATIONS AND DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT POLICIES 2011- 2026 (SADMP) Venues: Week 1 30th September Committee Suite, King’s Court 1st October Wembley Room, Lynnsport 2nd October Wembley Room, Lynnsport Week 2 3rd November South Lynn Community Centre 4th November South Lynn Community Centre 5th November South Lynn Community Centre Week 3 17th November Wembley Room, Lynnsport 18th November Committee Suite, King’s Court 19th November Wembley Room, Lynnsport Addresses: Committee Suite, Borough Council of King’s Lynn & West Norfolk Offices, King’s Court, Chapel Street, King’s Lynn PE30 1EX Wembley Room, Lynnsport, Greenpark Avenue, King’s Lynn PE30 2NB South Lynn Community Centre, 10 St Michaels Road, King’s Lynn PE30 5HE Please note the earlier start time of 9.30am for the weeks starting 3rd November and 17th November – with the exception of Wednesday 18th November. If you have any queries – please contact the Programme Officer at: [email protected]