When the NCAA Strikes, Who Is Called Out?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAROLINA PANTHERS at NEW ORLEANS SAINTS MAKE YOU LOOK JANUARY 7, 2018• MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME • NEW ORLEANS, LA

WE CAROLINA PANTHERS AT NEW ORLEANS SAINTS MAKE YOU LOOK JANUARY 7, 2018• MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME • NEW ORLEANS, LA. • 3:40 PM GOOD ON PAPER. CAROLINA PANTHERS SAINTS defense SAINTS offense NEW ORLEANS SAINTS NO. NAME . P OS . NO. NAME . POS. 1 CAM NEWTON. QB LDE 94 CAMERON JORDAN 97 Al Quadin Muhammad WR 19 TED GINN JR. 83 Willie Snead IV 11 Tommylee Lewis 3 WIL LUTZ. K 3 DEREK ANDERSON . QB 6 THOMAS MORSTEAD. P LT 72 TERRON ARMSTEAD 4 GARRETT GILBERT . QB LDT 98 SHELDON RANKINS 76 Tony McDaniel 7 TAYSOM HILL. QB 5 MICHAEL PALARDY. P 9 DREW BREES. QB RDT 95 TYELER DAVISON 93 David Onyemata LG 75 ANDRUS PEAT 65 Senio Kelemete 77 John Fullington 9 GRAHAM GANO. K 10 CHASE DANIEL. QB C 60 MAX UNGER 61 Josh LeRibeus 63 Cameron Tom 11 BRENTON BERSIN. WR RDE 91 TREY HENDRICKSON 90 George Johnson 58 Kasim Edebali 11 TOMMYLEE LEWIS. WR 12 KAELIN CLAY. WR RG 67 LARRY WARFORD 13 MICHAEL THOMAS. WR 14 MOSE FRAZIER. WR WILL 52 CRAIG ROBERTSON 16 BRANDON COLEMAN. WR RT 71 RYAN RAMCZYK 17 DEVIN FUNCHESS . WR ED INN R MLB 51 MANTI TE’O 50 Gerald Hodges 19 T G J .. .WR 19 RUSSELL SHEPARD. .WR TE 89 JOSH HILL 84 Michael Hoomanawanui 86 John Phillips 20 KEN CRAWLEY. CB 20 KURT COLEMAN. FS SAM 56 MICHAEL MAUTI 55 Jonathan Freeny 22 MARK INGRAM II. RB WR 13 MICHAEL THOMAS 16 Brandon Coleman 80 Austin Carr 22 CHRISTIAN MCCAFFREY. RB 23 MARSHON LATTIMORE. CB LCB 20 KEN CRAWLEY 26 P.J. -

DENVER BRONCOS Vs. BUFFALO BILLS SUNDAY, DEC

DENVER BRONCOS vs. BUFFALO BILLS SUNDAY, DEC. 7, 2014 • 2:05 P.M. MST • SPORTS AUTHORITY FIELD AT MILE HIGH • DENVER BRONCOS NUMERICAL BRONCOS 2014 SCHEDULE BRONCOS OFFENSE BRONCOS DEFENSE BILLS 2014 SCHEDULE BILLS NUMERICAL No. Player Pos. Wk. Date Opponent Time/Res. Wk. Date Opponent Time/Res. No. Player Pos. 1 Connor Barth . K WR 88 Demaryius Thomas 12 Andre Caldwell LDE 95 Derek Wolfe 97 Malik Jackson 2 Dan Carpenter . K 4 Britton Colquitt . P 1 Sept . 7 vs . Indianapolis W, 31-24 1 Sept . 7 at Chicago W, 23-20 OT 3 EJ Manuel . QB 10 Emmanuel Sanders . WR LT 78 Ryan Clady 75 Chris Clark DT 92 Sylvester Williams 96 Mitch Unrein 2 Sept . 14 vs . Miami W, 29-10 4 Jordan Gay . K 2 Sept . 14 vs . Kansas City W, 24-17 6 Colton Schmidt . P 12 Andre Caldwell . .WR LG 74 Orlando Franklin 63 Ben Garland 3 Sept . 21 vs . San Diego L, 10-22 14 Cody Latimer . WR 3 Sept . 21 at Seattle L, 20-26 (OT) NT 98 Terrance Knighton 76 Marvin Austin Jr . 10 Robert Woods . WR 17 Brock Osweiler . QB 4 Sept . 28 BYE C 64 Will Montgomery 66 Manny Ramirez 4 Sept . 28 at Houston L, 17-23 11 Marcus Thigpen . WR 18 Peyton Manning . QB RDE 94 DeMarcus Ware 93 Quanterus Smith 14 Sammy Watkins . WR 5 Oct . 5 vs . Arizona W, 41-20 RG 66 Manny Ramirez 63 Ben Garland 5 Oct . 5 at Detroit W, 17-14 15 Chris Hogan . WR 19 Isaiah Burse . .WR SLB 58 Von Miller 55 Lerentee McCray 6 Oct . -

The Fifth Down

Members get half off on June 2006 Vol. 44, No. 2 Outland book Inside this issue coming in fall The Football Writers Association of President’s Column America is extremely excited about the publication of 60 Years of the Outland, Page 2 which is a compilation of stories on the 59 players who have won the Outland Tro- phy since the award’s inception in 1946. Long-time FWAA member Gene Duf- Tony Barnhart and Dennis fey worked on the book for two years, in- Dodd collect awards terviewing most of the living winners, spin- ning their individual tales and recording Page 3 their thoughts on winning major-college football’s third oldest individual award. The 270-page book is expected to go on-sale this fall online at www.fwaa.com. All-America team checklist Order forms also will be included in the Football Hall of Fame, and 33 are in the 2006-07 FWAA Directory, which will be College Football Hall of Fame. Dr. Outland Pages 4-5 mailed to members in late August. also has been inducted posthumously into As part of the celebration of 60 years the prestigious Hall, raising the number to 34 “Outland Trophy Family members” to of Outland Trophy winners, FWAA mem- bers will be able to purchase the book at be so honored . half the retail price of $25.00. Seven Outland Trophy winners have Nagurski Award watch list Ever since the late Dr. John Outland been No. 1 picks overall in NFL Drafts deeded the award to the FWAA shortly over the years, while others have domi- Page 6 before his death, the Outland Trophy has nated college football and pursued greater honored the best interior linemen in col- heights in other areas upon graduation. -

108843 FB MG Text 111-208.Indd

2005OPPONENTS IDAHO AT NEVADA IDAHO NEVADA SEPTEMBER 1 SEPTEMBER 9 TBA 7:00 p.m. PULLMAN RENO 2005 SCHEDULE VANDAL INFORMATION 2005 SCHEDULE WOLF PACK INFORMATION 2005 OUTLOOK Sept. 1 at Washington State LOCATION: Moscow, Idaho Sept. 9 WASHINGTON STATE LOCATION: Reno, Nev. Sept. 10 at UNLV NICKNAME: Vandals Sept. 17 UNLV NICKNAME: Wolf Pack Sept. 17 at Washington COLORS: Silver and Gold Sept. 24 at Colorado State COLORS: Navy Blue and Silver Sept. 24 HAWAI’I PRESIDENT: Dr. Timothy White Oct. 1 at San Jose State PRESIDENT: Dr. John Lilley Oct. 1 UTAH STATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR: Dr. Rob Spear Oct. 8 IDAHO ATHLETIC DIRECTOR: Cary Groth Oct. 8 at Nevada CONFERENCE: Western Athletic Oct. 15 LOUISIANA TECH CONFERENCE: Western Athletic Oct. 22 FRESNO STATE ENROLLMENT: 12,894 Oct. 29 at Boise State ENROLLMENT: 16,500 Oct. 29 at New Mexico State STADIUM: Kibbie Dome (16,000, arti- Nov. 5 HAWAI’I STADIUM: Mackay Stadium (31,900, Nov. 12 LOUISIANA TECH fi cial turf) Nov. 12 at New Mexico State FieldTurf) Nov. 19 at Boise State WEB SITE: www.uiathletics.com Nov. 19 at Utah State WEB SITE: www.nevadawolfpack.com Nov. 26 at San Jose State Nov. 26 FRESNO STATE IDAHO STAFF NEVADA STAFF 2004 RESULTS (3-9/2-5/T7TH) HEAD COACH: Nick Holt (Pacifi c, 2004 RESULTS (5-7/3-5/T6TH) HEAD COACH: Chris Ault (Neveda, WSU COACHES Sept. 4 at Boise State L, 7-65 1986) Sept. 6 at Louisiana Tech L, 38-21 1968) Sept. 11 at Utah State L, 7-14 Record at School: 3-9 (1 year) Sept. -

The Following Players Comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set

COLLEGE FOOTBALL GREAT TEAMS OF THE PAST 2 SET ROSTER The following players comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. 1971 NEBRASKA 1971 NEBRASKA 1972 USC 1972 USC OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Woody Cox End: John Adkins EB: Lynn Swann TA End: James Sims Johnny Rodgers (2) TA TB, OA Willie Harper Edesel Garrison Dale Mitchell Frosty Anderson Steve Manstedt John McKay Ed Powell Glen Garson TC John Hyland Dave Boulware (2) PA, KB, KOB Tackle: John Grant Tackle: Carl Johnson Tackle: Bill Janssen Chris Chaney Jeff Winans Daryl White Larry Jacobson Tackle: Steve Riley John Skiles Marvin Crenshaw John Dutton Pete Adams Glenn Byrd Al Austin LB: Jim Branch Cliff Culbreath LB: Richard Wood Guard: Keith Wortman Rich Glover Guard: Mike Ryan Monte Doris Dick Rupert Bob Terrio Allan Graf Charles Anthony Mike Beran Bruce Hauge Allan Gallaher Glen Henderson Bruce Weber Monte Johnson Booker Brown George Follett Center: Doug Dumler Pat Morell Don Morrison Ray Rodriguez John Kinsel John Peterson Mike McGirr Jim Stone ET: Jerry List CB: Jim Anderson TC Center: Dave Brown Tom Bohlinger Brent Longwell PC Joe Blahak Marty Patton CB: Charles Hinton TB. -

FINAL TOP 10 POLLS ASSOCIATED PRESS (1936-Present) 1936 1943 1950 1956 1962 1969 1

FINAL TOP 10 POLLS ASSOCIATED PRESS (1936-Present) 1936 1943 1950 1956 1962 1969 1. Minnesota 1. Notre Dame 1. Oklahoma 1. Oklahoma 1. USC 1. Texas 2. LSU 2. Iowa Pre-Flight 2. Army 2. Tennessee 2. Wisconsin 2. Penn State 3. Pittsburgh 3. Michigan 3. Texas 3. Iowa 3. Mississippi 3. USC 4. Alabama 4. Navy 4. Tennessee 4. Georgia Tech 4. Texas 4. Ohio State 5. Washington 5. Purdue 5. California 5. Texas A&M 5. Alabama 5. Notre Dame 6. Santa Clara 6. Great Lakes 6. Princeton 6. Miami (Fla.) 6. Arkansas 6. Missouri 7. Northwestern 7. Duke 7. Kentucky 7. Michigan 7. LSU 7. Arkansas 8. Notre Dame 8. Del Monte 8. Michigan State 8. Syracuse 8. Oklahoma 8. Mississippi 9. Nebraska 9. Northwestern 9. Michigan 9. Michigan State 9. Penn State 9. Michigan 10. Pennsylvania 10. March Field 10. Clemson 10. Oregon State 10. Minnesota 10. LSU 18. USC 1937 1944 1951 1963 1970 1. Pittsburgh 1. Army 1. Tennessee 1957 1. Texas 1. Nebraska 2. California 2. Ohio State 2. Michigan State 1. Auburn 2. Navy 2. Notre Dame 3. Fordham 3. Randolph Field 3. Maryland 2. Ohio State 3. Illinois 3. Texas 4. Alabama 4. Navy 4. Illinois 3. Michigan State 4. Pittsburgh 4. Tennessee 5. Minnesota 5. Bainbridge 5. Georgia Tech 4. Oklahoma 5. Auburn 5. Ohio State 6. Iowa Pre-Flight 6. Villanova 6. Princeton 5. Navy 6. Nebraska 6. Arizona State 7. USC 7. Dartmouth 7. Stanford 6. Iowa 7. Mississippi 7. LSU 8. Michigan 8. LSU 8. Wisconsin 7. -

The Absolute Power the NFL's Collective Bargaining Agreement

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 82 | Issue 1 Article 10 Fall 12-1-2016 Between the Hash Marks: The Absolute Power the NFL’s Collective Bargaining Agreement Grants Its Commissioner Eric L. Einhorn Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Eric L. Einhorn, Between the Hash Marks: The Absolute Power the NFL’s Collective Bargaining Agreement Grants Its Commissioner, 82 Brook. L. Rev. (2016). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol82/iss1/10 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. Between the Hash Marks THE ABSOLUTE POWER THE NFL’S COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT GRANTS ITS COMMISSIONER INTRODUCTION For many Americans, Sundays revolve around one thing—the National Football League (the NFL or the League). Fans come from all over to watcH their favorite teams compete and partake in a sport that has become more than just a game. Sunday worries for NFL fans consist of painting their faces, tailgating, and setting their fantasy lineups.1 For professional football players, football is a way to earn a living; touchdowns, yards, and big hits highlight ESPN’s top plays,2 generating a multibillion-dollar industry.3 Like the other three major sports leagues,4 the NFL is governed by a multitude of intricate rules, regulations, and agreements that dictate the employment and 1 Fantasy sports involve fans signing up for a league and creating a virtual team. -

2016 FOOTBALL ROSTER RATINGS SHEET Updated 8/1/2017

2016 FOOTBALL ROSTER RATINGS SHEET Updated 8/1/2017 AFC East 37 35 39 BUFFALO OFFENSE 37 35 39 POSITION B P R B P R B P R B P R B P R B P R QB Tyrod Taylor 3 3 4 EJ Manuel 2 2 2 Cardale Jones 1 1 1 HB LeSean McCoy 4 4 4 Mike Gillislee OC 3 3 3 Reggie Bush TC OC 2 2 2 Jonathan Williams 2 2 2 WR Robert Woods 3 3 3 Percy Harvin 2 2 2 Dezmin Lewis 1 1 1 Greg Salas 1 2 1 TE Charles Clay 3 3 3 Nick O'Leary OC 2 2 2 Gerald Christian 1 1 1 T Cordy Glenn 3 3 4 Michael Ola 2 2 2 Seantrel Henderson 2 2 2 T Jordan Mills 4 3 4 Cyrus Kouandjio 2 3 2 G Richie Incognito 4 4 4 G John Miller 3 3 3 WR Marquise Goodwin 3 3 3 Justin Hunter 2 2 2 C Eric Wood 4 3 4 Ryan Groy 2 3 2 Garrison Sanborn 2 2 2 Gabe Ikard 1 1 1 Patrick Lewis 1 1 1 WR Sammy Watkins 3 3 3 Walt Powell 2 2 2 Brandon Tate TA TB OA OB 1 1 1 FB/TE Jerome Felton OC 2 2 2 Glenn Gronkowski 1 1 1 AFC East 36 38 34 BUFFALO DEFENSE 36 38 34 POSITION B P R B P R B P R B P R B P R B P R DT Adolphus Washington 2 3 2 Deandre Coleman 1 1 1 DT/DE Kyle Williams 3 4 3 Leger Douzable 3 3 3 Jerel Worthy 2 2 2 LB Lorenzo Alexander 5 5 5 Bryson Albright 1 1 1 MLB Preston Brown 3 3 3 Brandon Spikes 2 2 2 LB Zach Brown 5 5 5 Ramon Humber 2 2 2 Shaq Lawson 2 2 2 LB Jerry Hughes 3 3 3 Lerentee McCray 2 2 2 CB Ronald Darby 3 3 2 Marcus Roberson 2 2 2 CB Stephon Gilmore 3 3 3 Kevon Seymour 2 2 2 FS Corey Graham 3 3 3 Colt Anderson 2 2 2 Robert Blanton 2 2 2 SS Aaron Williams 3 3 2 Sergio Brown 2 2 2 Jonathan Meeks 2 2 2 NT Marcell Dareus 3 3 3 Corbin Bryant 2 3 2 DB James Ihedigbo 3 3 2 Nickell Robey-Coleman 2 3 -

BASE CARDS 1 Aaron Rodgers Green Bay Packers 51 Jason Witten Dallas Cowboys 2 Troy Polamalu Pittsburgh Steelers 52 Steven Jackson St

BASE CARDS 1 Aaron Rodgers Green Bay Packers 51 Jason Witten Dallas Cowboys 2 Troy Polamalu Pittsburgh Steelers 52 Steven Jackson St. Louis Rams 3 Josh Freeman Tampa Bay Buccaneers 53 Carson Palmer Oakland Raiders 4 Kenny Britt Tennessee Titans 54 Miles Austin Dallas Cowboys 5 Dez Bryant Dallas Cowboys 55 Jay Cutler Chicago Bears 6 Victor Cruz New York Giants 56 Brandon Pettigrew Detroit Lions 7 Jahvid Best Detroit Lions 57 Jared Allen Minnesota Vikings 8 Jimmy Graham New Orleans Saints 58 Mario Williams Buffalo Bills 9 Demaryius Thomas Denver Broncos 59 Jamaal Charles Kansas City Chiefs 10 Cam Newton Carolina Panthers 60 Peyton Manning Indianapolis Colts 11 Jason Pierre-Paul New York Giants 61 Jordy Nelson Green Bay Packers 12 Vernon Davis San Francisco 49ers 62 Reggie Bush Miami Dolphins 13 Rashard Mendenhall Pittsburgh Steelers 63 Joe Flacco Baltimore Ravens 14 Marshawn Lynch Seattle Seahawks 64 Sam Bradford St. Louis Rams 15 Andy Dalton Cincinnati Bengals 65 Philip Rivers San Diego Chargers 16 Beanie Wells Arizona Cardinals 66 Daniel Thomas Miami Dolphins 17 Patrick Willis San Francisco 49ers 67 Steve Smith Carolina Panthers 18 Maurice Jones-Drew Jacksonville Jaguars 68 Ahmad Bradshaw New York Giants 19 Julio Jones Atlanta Falcons 69 Roddy White Atlanta Falcons 20 Calvin Johnson Detroit Lions 70 Adrian Peterson Minnesota Vikings 21 LaDainian Tomlinson New York Jets 71 Cedric Benson Cincinnati Bengals 22 Anquan Boldin Baltimore Ravens 72 A.J. Green Cincinnati Bengals 23 Andre Johnson Houston Texans 73 Rob Gronkowski New England Patriots -

2009 Dr Pepper Big 12 Football Championship

2009 DR PEPPER BIG 12 FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIP 2009 STANDINGS BIG 12 GAMES OVERALL NORTH DIVISION W-L Pct. PF PA W-L Pct. PF PA Home Road Neutral vs. Div. vs. Top 25 Streak Nebraska 6-2 .750 150 105 9-3 .750 307 133 5-2 4-1 0-0 4-1 2-1 Won 5 Missouri 4-4 .500 217 233 8-4 .667 364 295 3-3 3-1 2-0 4-1 0-3 Won 3 Kansas State 4-4 .500 182 216 6-6 .500 276 280 5-1 0-5 1-0 3-2 0-2 Lost 2 Iowa State 3-5 .375 151 195 6-6 .500 253 271 4-2 2-3 0-1 2-3 0-2 Lost 1 Colorado 2-6 .250 164 234 3-9 .250 267 346 3-3 0-6 0-0 1-4 1-3 Lost 3 Kansas 1-7 .125 191 287 5-7 .417 353 341 4-2 1-4 0-1 1-4 0-2 Lost 7 SOUTH DIVISION Texas 8-0 1.000 317 145 12-0 1.000 516 185 6-0 5-0 1-0 5-0 2-0 Won 16 Oklahoma State 6-2 .750 206 176 9-3 .750 362 261 6-2 3-1 0-0 3-2 2-1 Lost 1 Texas Tech 5-3 .625 271 181 8-4 .667 440 261 6-1 1-3 1-0 2-3 1-3 Won 2 Oklahoma 5-3 .625 231 127 7-5 .583 373 162 6-0 1-3 0-2 3-2 2-3 Won 1 Texas A&M 3-5 .375 253 290 6-6 .500 407 392 5-2 1-3 0-1 2-3 1-2 Lost 1 Baylor 1-7 .125 104 248 4-8 .333 249 327 2-4 2-3 0-1 0-5 0-3 Lost 3 BIG 12 FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIP - SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Friday, December 4 Noon and 1:00 p.m. -

1423 a Microcosm of Our Broken Society (Sports)

#1423 A Microcosm of our Broken Society (Sports) JAY TOMLINSON - HOST, BEST OF THE LEFT: [00:00:00] Welcome to this episode of the award-winning Best of the Le; podcast in which we shall look at the poli=cs of sports, including racism, sexism, capitalism, media, and mental health. So, preCy much just like regular poli=cs, but with the one group of rich people who society broadly thinks don't have a right to be heard. Clips today are from Why is This Happening With Chris Hayes; Cita=ons Needed; The Damage Report; TYT Sports; Vice News; Edge of Sports; Past Present; and The Old Man and the Three. THe Uneven PLaying FieLd witH Howard Bryant - WHy Is THis Happening? witH CHris Hayes - Air Date 1-21-20 HOWARD BRYANT: [00:00:34] Sports, and the culture... it's mirroring each other in so many different ways, where you're star=ng to see... Okay, like the sec=on in the book is called "The Jokes On You," where the numerous opportuni=es to cheat... it's like it's open season. Whether you're talking about the Cabinet, whether you're talking about what's happening in sports, whether you're talking about the priva=za=on of public money, all of it. It's the same "If you ain't chea=ng, you ain't trying" a]tude. CHRIS HAYES - HOST, WHY IS THE HAPPENING?: [00:00:58] That's such a good point because, and the crazy thing too, and one of the ways that I think that sports and society mirror each other, is that we have increasingly adopted a kind of compe==ve ethos in non sport situa=ons, HOWARD BRYANT: [00:01:12] That's right! CHRIS HAYES - HOST, WHY IS THE HAPPENING?: [00:01:12] Right? Like the way that firms are run, the way that we think about like the market driving, everything, the idea that like, the person that makes the most money wins the superstar performers, HOWARD BRYANT: [00:01:21] That idea of meritocracy. -

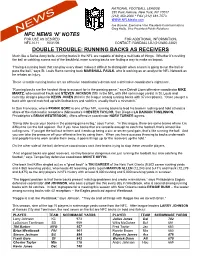

Nfc News 'N' Notes Double Trouble: Running Backs As

NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE 280 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017 (212) 450-2000 * FAX (212) 681-7573 WWW.NFLMedia.com Joe Browne, Executive Vice President-Communications Greg Aiello, Vice President-Public Relations NFC NEWS ‘N’ NOTES FOR USE AS DESIRED FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION, NFC-N-11 10/31/06 CONTACT: RANDALL LIU (212/450-2382) DOUBLE TROUBLE: RUNNING BACKS AS RECEIVERS Much like a Swiss Army knife, running backs in the NFL are capable of doing a multitude of things. Whether it’s rushing the ball or catching a pass out of the backfield, more running backs are finding a way to make an impact. “Having a running back that can play every down makes it difficult to distinguish when a team is going to run the ball or pass the ball,” says St. Louis Rams running back MARSHALL FAULK, who is working as an analyst for NFL Network as he rehabs an injury. These versatile running backs are an offensive coordinator’s dream and a defensive coordinator’s nightmare. “Running backs are the hardest thing to account for in the passing game,” says Detroit Lions offensive coordinator MIKE MARTZ, who coached Faulk and STEVEN JACKSON (fifth in the NFL with 884 scrimmage yards) in St. Louis and currently designs plays for KEVIN JONES (third in the league among running backs with 37 receptions). “Once you get a back with speed matched up with linebackers and safeties, usually that’s a mismatch.” In San Francisco, where FRANK GORE is one of four NFL running backs to lead his team in rushing and hold at least a share of the club lead in receptions (Minnesota’s CHESTER TAYLOR, San Diego’s LA DAINIAN TOMLINSON, Philadelphia’s BRIAN WESTRBOOK), 49ers offensive coordinator NORV TURNER agrees.