William Billings^S Hnthemfor Easter^: the Persistence of an Early American 'Hit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Land of Harmony a M E R I C a N C H O R a L G E M S

invites you to The Land of Harmony A MERIC A N C HOR A L G EMS April 5 • Shaker Heights April 6 • Cleveland QClevelanduire Ross W. Duffin, Artistic Director The Land of Harmony American Choral Gems from the Bay Psalm Book to Amy Beach April 5, 2014 April 6, 2014 Christ Episcopal Church Historic St. Peter Church shaker heights cleveland 1 Star-spangled banner (1814) John Stafford Smith (1750–1836) arr. R. Duffin 2 Psalm 98 [SOLOISTS: 2, 3, 5] Thomas Ravenscroft (ca.1590–ca.1635) from the Bay Psalm Book, 1640 3 Psalm 23 [1, 4] John Playford (1623–1686) from the Bay Psalm Book, 9th ed. 1698 4 The Lord descended [1, 7] (psalm 18:9-10) (1761) James Lyon (1735–1794) 5 When Jesus wep’t the falling tear (1770) William Billings (1746–1800) 6 The dying Christian’s last farewell (1794) [4] William Billings 7 I am the rose of Sharon (1778) William Billings Solomon 2:1-8,10-11 8 Down steers the bass (1786) Daniel Read (1757–1836) 9 Modern Music (1781) William Billings 10 O look to Golgotha (1843) Lowell Mason (1792–1872) 11 Amazing Grace (1847) [2, 5] arr. William Walker (1809–1875) intermission 12 Flow gently, sweet Afton (1857) J. E. Spilman (1812–1896) arr. J. S. Warren 13 Come where my love lies dreaming (1855) Stephen Foster (1826–1864) 14 Hymn of Peace (1869) O. W. Holmes (1809–1894)/ Matthias Keller (1813–1875) 15 Minuet (1903) Patty Stair (1868–1926) 16 Through the house give glimmering light (1897) Amy Beach (1867–1944) 17 So sweet is she (1916) Patty Stair 18 The Witch (1898) Edward MacDowell (1860–1908) writing as Edgar Thorn 19 Don’t be weary, traveler (1920) [6] R. -

Dissonance Treatment in Fuging Tunes by Daniel Read

NA7c DISSONANCE TREATMENT IN FUGING TUNES BY DANIEL READ FROM THE AMERICAN SINGING BOOK AND THE COLUMBIAN HARMONIST THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the' North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Scott G. Sims, B.M. Denton, Texas May, 1987 4vv , f\ Sims, Scott G., Dissonance Treatment in Fuging Tunes by Daniel Read from The American Singing Book and The Columbian Harmonist. Master of Music (Music Theory), May, 1987, 101 pp., 2 tables, 8 figures, 44 musical examples, 83 titles. This thesis treats Daniel Read's music analytically to establish style characteristics. Read's fuging tunes are examined for metric placement and structural occurrence of dissonance, and dissonance as text painting. Read's comments on dissonance are extracted from his tunebook introductions. A historical chapter includes the English origins of the fuging tune and its American heyday. The creative life of Daniel Read is discussed. This thesis contributes to knowledge of Read's role in the development of the New England Psalmody idiom. Specifically, this work illustrates the importance of understanding and analyzing Read's use of dissonance as a style determinant, showing that Read's dissonance treatment is an immediate and central characteristic of his compositional practice. Copyright by Scott G. Sims 1987 iii PREFACE The author wishes to thank The Lorenz Publishing Company for use of the following article: Metcalf, Frank, "Daniel Read and His Tune," The Choir Herald, XVII (April, 1914) , 124, 146-147. Copyright 1914, Renewal Secured, Lorenz Publishing Co., Used by Permission. -

The Evolution of American Choral Music: Roots, Trends, and Composers Before the 20Th Century James Mccray

The Evolution of American Choral Music: Roots, Trends, and Composers before the 20th Century James McCray I hear America singing, the varied car- such as Chester, A Virgin Unspotted, ols I hear. David’s Lamentation, Kittery, I Am the —Walt Whitman Rose of Sharon, and The Lord Is Ris’n Leaves of Grass1 Indeed received numerous performanc- es in concerts by church, school, com- Prologue munity, and professional choirs. Billings Unlike political history, American cho- generally is acknowledged to be the most ral music did not immediately burst forth gifted of the “singing school” composers with signifi cant people and events. Choral of eighteenth-century America. His style, music certainly existed in America since somewhat typical of the period, employs the Colonial Period, but it was not until fuguing tunes, unorthodox voice lead- the twentieth century that its impact was ing, open-fi fth cadences, melodic writing signifi cant. The last half of the twentieth in each of the parts, and some surpris- century saw an explosion of interest in ing harmonies.11 By 1787 his music was choral music unprecedented in the his- widely known across America. tory of the country. American choral mu- Billings was an interesting personal- sic came of age on a truly national level, ity as well. Because out-of-tune singing and through the expansion of music edu- was a serious problem, he added a ’cello cation, technology, professional organiza- to double the lowest part.12 He had a tions, and available materials, the interest “church choir,” but that policy met re- in choral singing escalated dramatically. -

Saving America from the Radical Left COVER the Radical Left Nearly Succeeded in Toppling the United States Republic

MAY-JUNE 2018 | THETRUMPET.COM Spiraling into trade war Shocking Parkland shooting story you have not heard Why U.S. men are failing China’s great leap toward strongman rule Is commercial baby food OK? Saving America from the radical left COVER The radical left nearly succeeded in toppling the United States republic. MAY-JUNE 2018 | VOL. 29, NO. 5 | CIRC.262,750 (GARY DORNING/TRUMPET, ISTOCK.COM/EUGENESERGEEV) We are getting a hard look at just what the radical left is willing to do in order to TARGET IN SIGHT seize power and President-elect Donald Trump meets with stay in power. President Barack Obama in the Oval Office in November 2016. FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 1 FROM THE EDITOR 18 INFOGRAPHIC 28 WORLDWATCH COVER STORY A Coming Global Trade War Saving America From the Radical 31 SOCIETYWATCH Left—Temporarily 20 China’s Great Leap Toward Strongman Rule 33 PRINCIPLES OF LIVING 4 1984 and the Liberal Left Mindset The Best Marriage Advice in 22 What Will Putin Do With Six More the World 6 The Parkland Shooting: The Years of Power? Shocking Story You Have Not Heard 34 DISCUSSION BOARD 26 Italy: Game Over for Traditional 10 Why American Men Are Failing Politics 35 COMMENTARY America’s Children’s Crusade 13 Commercial Baby Food: A Formula for Health? 36 THE KEY OF DAVID TELEVISION LOG 14 Spiraling Into Trade War Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Trumpet executive editor Stephen News and analysis Regular news updates and alerts Flurry’s weekly television program Flurry’s television program updated daily from our website to your inbox theTrumpet.com/keyofdavid theTrumpet.com/trumpet_daily theTrumpet.com theTrumpet.com/go/brief FROM THE EDITOR Saving America From the Radical Left—Temporarily People do not realize just how close the nation is to collapse. -

Earl Mclain Owen, Jr.-The Life and Music of Supply Belcher (1751-1836), ((Handel of Maine" Volume L· Text, Xvii + 152 Pp

Earl McLain Owen, Jr.-The Life and Music of Supply Belcher (1751-1836), ((Handel of Maine" Volume L· Text, xvii + 152 pp. Volume IL' Musical Supplement, vi + 204 pp. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms (UM order no. 69-4446, 1969. D.M.A., Musicology, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary diss.) Sterling E. Murray American studies is a comparatively little-researched region of historical musicology. As with any youthful area of study the often laborious and frustrating task oflaying a basic bibliographical and biographical foundation must be accomplished before more definitive studies can be achieved. Dr. Owen's dissertation contributes to this growing foundation and, thus, to a developing knowledge of our musical heritage. Dr. Owen organizes his study in a deductive manner, progressing from an investigation of the composer's life to his musical publications and culminat- ing in a stylistic study of the music. In the introductory remarks of Chapter I, Dr. Owen explains that "on October 22, 1886, an extensive fire in the central district of Farmington quite possibly destroyed certain priceless documents such as letters, diaries, singing society records, etc. Therefore, it has been necessary that this investigator base his historical research mainly on secondary sources-nine- teenth century histories, correspondence with historians and libraries, and recently published books" (p. 1). This is a supposition, which the author does not attempt to justify. It is also "quite possible" that there were no records of any importance relating to Supply Belcher destroyed in the Farmington fire. Lack of primary biographical source material is a handicap, but, in spite of this limitation, Dr. -

Images of the Divine Vision in the Four Zoas

Oberlin Digital Commons at Oberlin Honors Papers Student Work 1973 Nature, Reason, and Eternity: Images of the Divine Vision in The Four Zoas Cathy Shaw Oberlin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Shaw, Cathy, "Nature, Reason, and Eternity: Images of the Divine Vision in The Four Zoas" (1973). Honors Papers. 754. https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors/754 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Digital Commons at Oberlin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Oberlin. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATURE, nEASON, and ETERNITY: Images of the Divine Vision in The }1'our Zoas by Cathy Shaw English Honors }i;ssay April 26,1973 In The Four Zoas Blake wages mental ,/Ur against nature land mystery, reason and tyranny. As a dream in nine nights, the 1..Jorld of The Four Zoas illustrates an unreal world which nevertheless represents the real t-lorld to Albion, the dreamer. The dreamer is Blake's archetypal and eternal man; he has fallen asleep a~ong the floitlerS of Beulah. The t-lorld he dreams of is a product of his own physical laziness and mental lassitude. In this world, his faculties vie 'tvi th each other for pOi-vel' until the ascendence of Los, the imaginative shapeI'. Los heralds the apocalypse, Albion rem-Jakas, and the itwrld takes on once again its original eternal and infinite form. -

New Night Thoughts Sightings First Noticed by Bentley in 1980

MINUTE PARTICULAR was desperate for cash, the presence of any plates and other potentially lucrative bibliographic details are carefully not- ed in both categories. It is possible, therefore, that the cat- alogue describes the unillustrated state of Night Thoughts, 6 New Night Thoughts Sightings first noticed by Bentley in 1980. Whether or not this is the case, Mills did know at least one of the Edwardses, and his bookplate is found in a copy of Junius’s Stat nominis umbra, By Wayne C. Ripley 2 vols. (London: T. Bensley, 1796-97), with the inscription “1796 B[ough]t. of Edwards.”7 As Bentley notes, the ini- Wayne C. Ripley ([email protected]) is an associ- tials “J / E”, James Edwards, appear on the inner front cov- ate professor of English at Winona State University in er of the unillustrated Night Thoughts. As my discovery of Minnesota. He is the co-editor of Editing and Reading the advertisements for volume 2 suggests, James may have been more involved in the production and distribution of Blake with Justin Van Kleeck for Romantic Circles. He 8 has written on Blake and Edward Young. the book than has been recognized. Unfortunately, if Mills did, in fact, own the unillustrated copy, the sales catalogue explains neither why he did so nor why the copy was creat- ed in the first place. 1 O my list of catalogue references to Blake’s Night T Thoughts, which was augmented by G. E. Bentley, Jr.,1 3 The second new listing occurs in A Catalogue of Books, for should be added eight new listings. -

The Ambiguity of “Weeping” in William Blake's Poetry

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 The Ambiguity of “Weeping” in William Blake’s Poetry Audrey F. Lytle Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Liberal Studies Commons, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Commons Recommended Citation Lytle, Audrey F., "The Ambiguity of “Weeping” in William Blake’s Poetry" (1968). All Master's Theses. 1026. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1026 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~~ THE AMBIGUITY OF "WEEPING" IN WILLIAM BLAKE'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Education by Audrey F. Lytle August, 1968 LD S77/3 I <j-Ci( I-. I>::>~ SPECIAL COLL£crtoN 172428 Library Central W ashingtoft State Conege Ellensburg, Washington APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ________________________________ H. L. Anshutz, COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN _________________________________ Robert Benton _________________________________ John N. Terrey TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION 1 Method 1 Review of the Literature 4 II. "WEEPING" IMAGERY IN SELECTED WORKS 10 The Marriage of Heaven and Hell 10 Songs of Innocence 11 --------The Book of Thel 21 Songs of Experience 22 Poems from the Pickering Manuscript 30 Jerusalem . 39 III. CONCLUSION 55 BIBLIOGRAPHY 57 APPENDIX 58 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION I. -

William Blake and Sexuality

ARTICLE Desire Gratified aed Uegratified: William Blake aed Sexuality Alicia Ostriker Blake/Ae Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 16, Issue 3, Wieter 1982/1983, pp. 156-165 PAGH 156 BLAKE AS lLLUSTHMLD QUARTERLY WINTER 1982-83 Desire Gratified and Ungratified: William Blake and Sexuality BY ALICIA OSTRIKEK To examine Blake on sexuality is to deal with a many-layered But Desire Gratified thing. Although we like to suppose that everything in the Plants fruits of life & beauty there (E 465) canon "not only belongs in a unified scheme but is in accord What is it men in women do require? with a permanent structure of ideas,"1 some of Blake's ideas The lineaments of Gratified Desire clearly change during the course of his career, and some What is it Women do in men require? others may constitute internal inconsistencies powerfully at The lineaments of Gratified Desire (E 466) work in, and not resolved by, the poet and his poetry. What It was probably these lines that convened me to Blake I will sketch here is four sets of Blakean attitudes toward sex- when I was twenty. They seemed obviously true, splendidly ual experience and gender relations, each of them coherent symmetrical, charmingly cheeky —and nothing else I had read and persuasive if not ultimately "systematic;" for conven- approached them, although I thought Yeats must have pick- ience, and in emulation of the poet's own method of per- ed up a brave tone or two here. Only later did I notice that the sonifying ideas and feelings, I will call them four Blakes. -

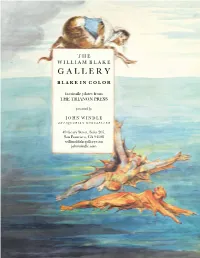

G a L L E R Y B L a K E I N C O L O R

T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E I N C O L O R facsimile plates from THE TRIANON PRESS presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 williamblakegallery.com johnwindle.com T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y TERMS: All items are guaranteed as described and may be returned within 5 days of receipt only if packed, shipped, and insured as received. Payment in US dollars drawn on a US bank, including state and local taxes as ap- plicable, is expected upon receipt unless otherwise agreed. Institutions may receive deferred billing and duplicates will be considered for credit. References or advance payment may be requested of anyone ordering for the first time. Postage is extra and will be via UPS. PayPal, Visa, MasterCard, and American Express are gladly accepted. Please also note that under standard terms of business, title does not pass to the purchaser until the purchase price has been paid in full. ILAB dealers only may deduct their reciprocal discount, provided the account is paid in full within 30 days; thereafter the price is net. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 233 San Francisco, CA 94108 T E L : (415) 986-5826 F A X : (415) 986-5827 C E L L : (415) 224-8256 www.johnwindle.com www.williamblakegallery.com John Windle: [email protected] Chris Loker: [email protected] Rachel Eley: [email protected] Annika Green: [email protected] Justin Hunter: [email protected] -

Musk in Manuscript a Massachusetts Tune-Book of 1782

Musk in Manuscript A Massachusetts Tune-book of 1782 RICHARD CRAWFORD AND DAVID P. McKAY J.HE characteristic musical publication of pre-Federal America was the tune collection. Especially popular were sacred tune- books, containing anywhere from a dozen to 100 or more dif- ferent pieces. Some 100 different issues devoted to sacred music had appeared in this country by 1786, when Chauncey Langdon's The Select Songster, the first printed American collection of secular songs with music, was published in New Haven by Daniel Bowen.^ Music also circulated in manuscript; 'The information about sacred music publication is taken from a bibliography of American sacred music through 1810 by Allen Britton, Irving Lowens, and Richard Crawford, to be published by the Society. The information about secular music is taken from Oscar Sonneck, Bibliography of Early Secular American Music, revised & enlarged by William Treat Upton {Washington: Library of Congress, 194^; reprinted, New York: Da Capo Press, 1964). Langdon's TAeA'e/eci Songj/fr had been preceded by only a meager scattering of non-sa- cred items; threePennsylvaniapublicationsof the early 1760s, TÍie Military Glory of Great Britain (Philadelphia: William Bradford, 1762) and A Dialogue on Peace (Philadelphia: William Bradford, 1763}, both perhaps by the psalmodist James Lyon, and John Stanley's music to the dramatic pastorale, Arcadia (Philadelphia: Andrew Stuart, 1762), no longer extant; single songs in two periodicals of the 1770s, THE HILL TOPS {Royal American Magazine, Boston, April, 1774-) -

![Articles "Blake, Thomas Boston, and the Fourfold Vision" (Blake 19 [1986]: 142) and "'W —M Among the Footnotes That Irritate Me Most (I Shall Call](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0753/articles-blake-thomas-boston-and-the-fourfold-vision-blake-19-1986-142-and-w-m-among-the-footnotes-that-irritate-me-most-i-shall-call-2530753.webp)

Articles "Blake, Thomas Boston, and the Fourfold Vision" (Blake 19 [1986]: 142) and "'W —M Among the Footnotes That Irritate Me Most (I Shall Call

MINUTE PARTICULAR The Orthodoxy of Blake Footnotes Michael Ferber Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 32, Issue 1, Summer 1998, pp. 16-19 If any readers in 1830 considered these affinities between The Orthodoxy of Blake Footnotes Blake and Hogg, they may also have recalled the cryptic allusion to "W — m B — e, a great original," in the ending BY MICHAEL FERBER of Hogg's greatest novel, six years earlier.22 Yet in spite of tempting evidence, none of the reviews of Cunningham in the Edinburgh Literary Journal can be proved he disheartening experience of reading the footnotes to to be Hogg's. The most that may safely be claimed is that TBlake's poems in recent student anthologies has Hogg probably saw, and enJoyed, those reviews, and he prob- launched little theories in my head. Is it a case of horror vacuP. ably read their comments on Blake. Like some readers of Some annotators seem unable to let a proper name go by the Journal, he may also have noticed the similarities be- without attaching an "explanation" to it; any explanation tween himself and Blake which that passage seems to sug- will serve, it seems, but preferably an "etymology." Or is it gest. the return of the repressed? Many of these notes have been refuted or strongly questioned for many years now. Is it a medieval deference to "authority"? If so, it is a selective def- erence, only to those with a loud, confident manner, such as Harold Bloom. Is it mere laziness? We need a note on "north- ern bar" so let's see what the last couple of anthologies said about it ..