James Rolfe's Vocal Chamber Music: a Performance Analysis and Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Bruneau and David Gordon Duke Jean Coulthard: a Life in Music

150 Historical Studies in Education / Revue d’histoire de l’éducation BOOK REVIEWS / COMPTES RENDUS William Bruneau and David Gordon Duke Jean Coulthard: A Life in Music. Vancouver: Ronsdale, 2005. 216 pp. William J. Egnatoff She “made sense of life by composing.” (p. 146) “My aim is simply to write music that is good . to minister to human welfare . [A] composer’s musical language should be instinctive, personal, and natural to him.” (p. 157) Bruneau and Duke’s illuminating guide to the life and music of Vancouver composer Jean Coulthard (“th” pronounced as in “Earth Music” (‘cello, 1986) or “Threnody” (various choral and instrumental, 1933, 1947, 1960, 1968, 1970, 1981, 1986) con- tributes substantially and distinctively in form and detail to the growing array of biographical material on internationally-known Canadian composers of the twen- tieth century. Coulthard (1908–2000) began writing music in childhood and con- tinued as long as she could. Composition dates in the 428-page catalogue of the Coulthard manuscripts which can be found at the Web page http://www.library. ubc.ca/archives/u_arch/2007.06.27.cat.pdf, and was prepared by the authors to accompany the posthumous third accession to the composer’s archives, range from 1917 to 1997. The catalogue is housed at the University of British Columbia at the Web site http://www.library.ubc.ca/archives/u_arch/coulth.html. Her works span all forms from delightful graded pieces for young piano students, through choral and chamber music, to opera and large orchestral scores. The book addresses students of Canadian classical music, women’s issues, and the performing arts. -

Report to the Friends of Music

Summer, 2020 Dear Friends of the Music Department, The 2019-20 academic year has been like no other. After a vibrant fall semester featur- ing two concerts by the Parker Quartet, the opening of the innovative Harvard ArtLab featuring performances by our faculty and students, an exciting array of courses and our inaugural department-wide throwdown–an informal sharing of performance projects by students and faculty–we began the second semester with great optimism. Meredith Monk arrived for her Fromm Professorship, Pedro Memelsdorff came to work with the Univer- sity Choir as the Christoph Wolff Scholar, Esperanza Spalding and Carolyn Abbate began co-teaching an opera development workshop about Wayne Shorter’s Iphigenia, and Vijay Iyer planned a spectacular set of Fromm Players concerts and a symposium called Black Speculative Musicalities. And then the world changed. Harvard announced on March 10, 2020 that due to COVID-19, virtual teaching would begin after spring break and the undergraduates were being sent home. We had to can- cel all subsequent spring events and radically revise our teaching by learning to conduct classes over Zoom. Our faculty, staff, and students pulled together admirably to address the changed landscape. The opera workshop (Music 187r) continued virtually; students in Vijay Iyer’s Advanced Ensemble Workshop (Music 171) created an album of original mu- sic, “Mixtape,” that is available on Bandcamp; Meredith Monk created a video of students in her choral class performing her work in progress, Fields/Clouds, and Andy Clark created an incredible performance of the Harvard Choruses for virtual graduation that involved a complicated process of additive recording over Zoom. -

Download Snow in Summer

About Snow in Summer Snow in Summer is the second in a series of concerts in Nicole Ge Li and Corey Hamm’s Snow in Summer erhu and piano project (PEP). Look for many more World Premieres at the next PEP concerts at the Sound of Dragon Festival (May 9-14, 2014 Roundhouse), May 24, 2014 (UBC Barnett Hall), and for the PEP double-CD release concert (Fall 2014), and tours of China and North America (2014/2015). Over forty Canadian and Chinese composers have already agreed to write works for erhu and piano to be premiered, recorded, and toured in both Canada and China. To date, the list of composers includes James Harley, Brian Cherney, Hope Lee, David Eagle, Douglas Finch, Daniel Marshall, Elizabeth Raum, Dai Fujikura, Alexis Renault, Michael Park, John Oliver, Scott Godin, Stephen Chatman, Keith Hamel, Bob Pritchard, Jordan Nobles, Jocelyn PEP Morlock, Gabriel Dharmoo, Paul Steenhuisen, Marc Mellits, Remy Siu, Dorothy Chang, Edward Top, Chris Gainey, Dubravko Pajalic, Jared Miller, Martin Ritter, Alyssa Aska, Alfredo Piano and Erhu Project Santa Ana, Francois Houle, Owen Underhill, Vivian Fung, Hope Lee, Jian Qiang Xu, Yuan Qing Li, Ying Jiang, Joshua Chan, Si Ang Chen, I Yu Wang, Laura Pettigrew, Laurie Radford, Chan Kan Nin, Alice Ho, Emily Doolittle. Nicole Ge Li erhu Corey Hamm piano Thank you! For all their support, PEP would like to thank: The Canada Council for the Arts, Canadian Jenny Lu poetry reader Music Centre, Fairchild Media Group, Lahoo, New Leaf Weekly, World Journal, UBC School of Music, Redshift Records, Consulate General -

FEATURE | Pondering the Direction of Canadian Classical Music by Jennifer Liu on February 4, 2017

FEATURE | Pondering The Direction Of Canadian Classical Music By Jennifer Liu on February 4, 2017 150 Years of History, Another Good 150 of Innovation: A commemoration of classical music in Canada. [excerpt: see full article here: http://www.musicaltoronto.org/2017/02/04/feature-pondering-the-question- of-canadian-classical-music/] Step into the future, and we see pianist Darren Creech stepping on stage in tropical short shorts, glittery hair and a big grin on his face. But in fact, as his audiences from Montreal to Toronto have witnessed, Darren has already pulled off the dress code to rave reviews, including for his Master’s graduation recital (to which a jury panelist gushed “LOVE those legs!”) How does Darren project his many identities through music — from his Mennonite heritage, to identifying as queer, to experiences from his eclectic childhood on three continents? Darren was born in Ottawa before his family went on the move — first to Texas, then to France, then to Dakar, Senegal. There on the African continent, Darren sought out a local piano teacher who had studied with the venerable pedagogue Alfred Cortot. Thus Darren gained his entry into the authentic classical tradition: through his teachers in Dakar and eventually in Canada, he is the direct heir to the musical lineages of Chopin and Beethoven. But how does a disciple carry out their legacy for today’s audiences, whether in Africa or in North America? Here Darren counters with a question: “Why perpetuate classical music in the context of social disparity. What is its relevance?” That was the probing sentiment that instilled his spirit to search for answers — and self-made opportunities. -

Howard Dyck Reflects on Glenn Gould's The

“What you intended to say”: Howard Dyck Reflects on Glenn Gould’s The Quiet in the Land Doreen Helen Klassen The Quiet in the Land is a radio documentary by Canadian pianist and composer Glenn Gould (1932-82) that features the voices of nine Mennonite musicians and theologians who reflect on their Mennonite identity as a people that are in the world yet separate from it. Like the other radio compositions in his The Solitude Trilogy—“The Idea of North” (1967) and “The Latecomers” (1969)—this work focuses on those who, either through geography, history, or ideology, engage in a “deliberate withdrawal from the world.”1 Based on Gould’s interviews in Winnipeg in July 1971, The Quiet in the Land was released by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) only in 1977, as Gould awaited changes in technology that would allow him to weave together snatches of these interviews thematically. His five primary themes were separateness, dealing with an increasingly urban and cosmopolitan lifestyle, the balance between evangelism and isolation, concern with others’ well-being in relation to the historic peace position, and maintaining Mennonite unity in the midst of fissions.2 He contextualized the documentary ideologically and sonically by placing it within the soundscape of a church service recorded at Waterloo-Kitchener United Mennonite Church in Waterloo, Ontario.3 Knowing that the work had received controversial responses from Mennonites upon its release, I framed my questions to former CBC radio producer Howard Dyck,4 one of Gould’s interviewees and later one of his 1 Bradley Lehman, “Review of Glenn Gould’s ‘The Quiet in the Land,’” www. -

American Masters 200 List Finaljan2014

Premiere Date # American Masters Program Title (Month-YY) Subject Name 1 ARTHUR MILLER: PRIVATE CONVERSATIONS On the Set of "Death of a Salesman" June-86 Arthur Miller 2 PHILIP JOHNSON: A SELF PORTRAIT June-86 Philip Johnson 3 KATHERINE ANNE PORTER: THE EYE OF MEMORY July-86 Katherine Anne Porter 4 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 1) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 5 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 2) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 6 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 3) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 7 BILLIE HOLIDAY: THE LONG NIGHT OF LADY DAY August-86 Billie Holiday 8 JAMES LEVINE: THE LIFE IN MUSIC August-86 James Levine 9 AARON COPLAND: A SELF PORTRAIT August-86 Aaron Copland 10 THOMAS EAKINS: A MOTION PORTRAIT August-86 Thomas Eakins 11 GEORGIA O'KEEFFE September-86 Georgia O'Keeffe 12 EUGENE O'NEILL: A GLORY OF GHOSTS September-86 Eugene O'Neill 13 ISAAC IN AMERICA: A JOURNEY WITH ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER July-87 Isaac Bashevis Singer 14 DIRECTED BY WILLIAM WYLER July-87 William Wyler 15 ARTHUR RUBENSTEIN: RUBENSTEIN REMEMBERED July-87 Arthur Rubinstein 16 ALWIN NIKOLAIS AND MURRAY LOUIS: NIK AND MURRAY July-87 Alwin Nikolais/Murray Louis 17 GEORGE GERSHWIN REMEMBERED August-87 George Gershwin 18 MAURICE SENDAK: MON CHER PAPA August-87 Maurice Sendak 19 THE NEGRO ENSEMBLE COMPANY September-87 Negro Ensemble Co. 20 UNANSWERED PRAYERS: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF TRUMAN CAPOTE September-87 Truman Capote 21 THE TEN YEAR LUNCH: THE WIT AND LEGEND OF THE ALGONQUIN ROUND TABLE September-87 Algonquin Round Table 22 BUSTER KEATON: A HARD ACT TO FOLLOW (Part 1) November-87 Buster Keaton 23 BUSTER KEATON: -

UBC High Notes

UBC High Notes 2009-2010 Season UBC High Notes The newsletter of the School of Music at the University of British Columbia I am delighted to welcome you to the eleventh edition of High Notes, in which we celebrate the recent activities and major achievements of faculty, staff and students in the UBC School of Music. I hope you enjoy this snapshot, which captures the diversity, quality, and impact of our activities and contributions — we are a vibrant community of creators, performers, and scholars! I warmly invite you to read about the School of Music in these pages, and to attend many of our performances in the coming months and years. The 2009-10 year is a significant anniversary for the School. UBC established its Department of Music in 1947 under the leadership of Harry Adaskin, and initially offered B.A. degrees with a major in Music. The Bachelor of Music degree was then developed with the first students entering in September 1959 (by which time the faculty also included other Canadian musical trailblazers like Jean Coulthard and Bar- bara Pentland). These 50 years have witnessed an impressive expansion in our degree programs, so that we now offer Bachelor’s, Master’s, and Doctoral programs in performance, music education, composition, music theory, musicology, and ethnomusicology. What started with a few dozen students has grown into a dynamic and diverse community of over 300 undergraduates and 130 graduate students. Music is thriving at UBC, and we continue to witness exciting increases in the size, quality, and scope of our programs. Our 50th Anniversary year is an opportunity to reflect with gratitude on the generous support the School has received from many donors, and with admiration on the countless contributions to musical performance and education that scores of faculty and thousands of alumni have made over the past five decades — throughout BC, across Canada, and around the world. -

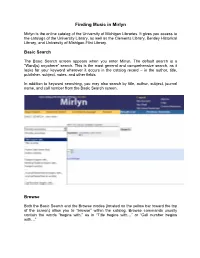

Finding Music in Mirlyn

Finding Music in Mirlyn Mirlyn is the online catalog of the University of Michigan Libraries. It gives you access to the catalogs of the University Library, as well as the Clements Library, Bentley Historical Library, and University of Michigan-Flint Library. Basic Search The Basic Search screen appears when you enter Mirlyn. The default search is a “Word(s) anywhere” search. This is the most general and comprehensive search, as it looks for your keyword wherever it occurs in the catalog record – in the author, title, publisher, subject, notes, and other fields. In addition to keyword searching, you may also search by title, author, subject, journal name, and call number from the Basic Search screen. Browse Both the Basic Search and the Browse modes (located on the yellow bar toward the top of the screen) allow you to “browse” within the catalog. Browse commands usually contain the words “begins with,” as in “Title begins with…” or “Call number begins with…” A browse results in an alphabetical or numerical (in the case of a call number search) list with your search term or the nearest match in the second position. For example, a “journal/serial name begins with” search on “rolling stone” retrieves the following: Advanced Search Advanced searching allows you to search by multiple parameters (e.g., author and title) at the same time. It also allows you to limit your search by format, language, location, and years; these options appear on the bottom half of the search screen. The following example is a subject search on “jazz” that has been limited to DVDs held by the Music Library: 2 Searching for Music When looking for music scores or recordings, “words anywhere” (aka keyword) searching is recommended. -

Maureen Batt, Soprano: Biography – May 2014 Noted by Opera Canada

Maureen Batt, soprano: Biography – May 2014 Noted by Opera Canada as a “young, lovely and captivating soprano,” and by the Halifax Herald as being “enthusiastically at home on stage” and having an “endlessly energetic and animated interpretation,” Maureen Batt is an accomplished concert and opera artist. Maureen’s opera credits include Belinda, Dido and Aeneas (Purcell), Silvia, L’isola disabitata (Haydn), Lauretta, Gianni Schicchi (Puccini), Rosa, Il campanello (Donizetti), Polly, The Threepenny Opera/Die Dreigroschenoper (Weill), Morgana, Alcina (Händel), Nina, Chérubin (Massenet), Susanna, Le nozze di Figaro (Mozart), Eusebia, Die Freunde von Salamanka (Schubert), Jenny, La Dame Blanche (Boieldieu), Papagena, Die ZauberFlöte (Mozart), Zerlina, Don Giovanni (Mozart), Annina, La Traviata (Verdi), Despina, Così Fan tutte (Mozart), Laetitia, The Old Maid and the ThieF (Menotti), Serpina, The Maid Mistress (Pergolesi), Limonia, Ten Belles Without a Ring (Von Suppe), Miss Silverpeal, The Impresario (Mozart). As an actor, she has appeared in Theatre St. Thomas University’s productions of Measure For Measure, Oh, What a Lovely War, and Caucasian Chalk Circle. She filmed a TV pilot for a series called Oznaberg, which premiered in the 2011 Silverwave Film Festival, and has since aired on Rogers Television. Her selected concert and oratorio credits include Handel’s Messiah and Esther, Mozart’s Vesperae solennes de ConFessore and Exsultate Jubilate, Bach’s BWV 187 Es wartet alles auF dich, BWV 4 Christ lag in Todes Banden, and BWV 245 St. John Passion. Maureen’s formal training includes a Master of Music from the University of Toronto, a Bachelor of Music from Dalhousie University, and a Bachelor of Arts from St. -

Filumena and the Canadian Identity a Research Into the Essence of Canadian Opera

Filumena and The Canadian Identity A Research into the Essence of Canadian Opera Alexandria Scout Parks Final thesis for the Bmus-program Icelandic Academy of the Arts Music department May 2020 Filumena and The Canadian Identity A Research into the Essence of Canadian Opera Alexandria Scout Parks Final Thesis for the Bmus-program Supervisor: Atli Ingólfsson Music Department May 2020 This thesis is a 6 ECTS final thesis for the B.Mus program. You may not copy this thesis in any way without consent from the author. Abstract In this thesis I sought to identify the essence of Canadian opera and to explore how the opera Filumena exemplifies that essence. My goal was to first establish what is unique about Canadian opera. To do this, I started by looking into the history of opera composition and performance in Canada. By tracing these two interlocking histories, I was able to gather a sense of the major bodies of work within the Canadian opera repertoire. I was, as well, able to deeper understand the evolution, and at some points, stagnation of Canadian opera by examining major contributing factors within this history. My next steps were to identify trends that arose within the history of opera composition in Canada. A closer look at many of the major works allowed me to see the similarities in terms of things such as subject matter. An important trend that I intend to explain further is the use of Canadian subject matter as the basis of the operas’ narratives. This telling of Canadian stories is one aspect unique to Canadian opera. -

MAGISTERRA-Canada-Fundraiser

MAGISTERRA SOLOISTS Magisterra Soloists is a vibrant Canadian classical music ensemble dedicated to programming innovative and venturesome chamber music works in juxtaposition with traditional staples of the classical repertoire. The ensemble brings together established professional musicians and young emerging artists from across the globe to create something fresh, engaging, and gutsy. In the context of its varied programming, Magisterra is delighted to collaborate with esteemed guest singers and instrumentalists. Magisterra is proud to offer its mentorship program, “Magisterra Fellows”, for select young artists who are invited to perform with the group. In the Spring of 2016, Magisterra launched its “Salon Series”, which is designed to offer music to more intimate audiences. Outside of its regular concert schedule, the ensemble presents concerts in schools throughout Ontario through its outreach program, “Magisterra in Schools”. Founded in the fall of 2015 by internationally-acclaimed German violinist, Annette-Barbara Vogel, Magisterra Soloists is currently based in London, Ontario. Within its first twelve months of concertizing, the ensemble performed to critical acclaim in more than two dozen of venues across Ontario, including Kingston’s Isabel Bader Centre for the Performing Arts. It has also succeeded in designing an educational program which provides interactive exposure to the arts for young children, and which it has presented to captivated audiences of both students and teachers in a number of schools throughout the province. In May of 2016, Magisterra Soloists gave the Canadian premiere of the ensemble’s first commission, Sapling, by award-winning Canadian composer Emily Doolittle. It subsequently premiered this work in August during its inaugural international six-city tour to Brazil which included performances in Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo, Porto Alegre, Belo Horizonte, Campinas, and Florianopolis, with the support of the Canadian Consulate in Rio de Janeiro. -

La Phil and Gustavo Dudamel Announce 2020/21 Season That Celebrates the Music of the Americas, Expands the Musical World with Mo

LA PHIL AND GUSTAVO DUDAMEL ANNOUNCE 2020/21 SEASON THAT CELEBRATES THE MUSIC OF THE AMERICAS, EXPANDS THE MUSICAL WORLD WITH MORE THAN TWO DOZEN COMMISSIONS, AND BRINGS EXCITING NEW VOICES TO BELOVED MASTERWORKS Dudamel launches multi-year Pan-American Music Initiative celebrating the vision and creativity of artists from across the Americas; inaugural year curated by composer Gabriela Ortiz features commissions and multi-disciplinary collaborations America: The Stories We Tell, a season-long musical journey into the ways in which narrative shapes American identity Seoul Festival, curated by composer Unsuk Chin, links South Korea’s cultural scene to the city with America’s largest Korean population The return of the landmark Tristan Project led by Esa-Pekka Salonen, with direction by Peter Sellars and visuals by Bill Viola, featuring Nina Stemme, Stephen Gould, Michelle DeYoung and Franz Josef Selig Katia and Marielle Labèque in an immersive multimedia journey, Supernova, with Barbara Hannigan and director Netia Jones, and concerts featuring new music by Nico Muhly and The National’s Bryce Dessner Season Subscription Series Available Now Single Ticket Sales Begin Sunday, August 23, 2020 Los Angeles, CA (February 5, 2020) – Los Angeles Philharmonic Music & Artistic Director Gustavo Dudamel and David C. Bohnett Chief Executive Officer Chair Chad Smith today announced the 2020/21 Walt Disney Concert Hall season featuring three trailblazing new projects: Pan-American Music Initiative and America: The Stories We Tell led by Gustavo Dudamel and Seoul Festival curated by Unsuk Chin; the premieres of 27 LA Phil commissions; the revival of LA Phil productions including the landmark Tristan Project Page 1 of 11 collaboration of Esa-Pekka Salonen, Peter Sellars and Bill Viola; and performances by world- renowned guest artists including Yuja Wang, Hélène Grimaud, Lang Lang, Itzhak Perlman, Yefim Bronfman, Leila Josefowicz, Katia and Marielle Labèque and Barbara Hannigan.