Psilocybin Dose-Dependently Causes Delayed, Transient Headaches in Healthy Volunteers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nitrate Prodrugs Able to Release Nitric Oxide in a Controlled and Selective

Europäisches Patentamt *EP001336602A1* (19) European Patent Office Office européen des brevets (11) EP 1 336 602 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.7: C07C 205/00, A61K 31/00 20.08.2003 Bulletin 2003/34 (21) Application number: 02425075.5 (22) Date of filing: 13.02.2002 (84) Designated Contracting States: (71) Applicant: Scaramuzzino, Giovanni AT BE CH CY DE DK ES FI FR GB GR IE IT LI LU 20052 Monza (Milano) (IT) MC NL PT SE TR Designated Extension States: (72) Inventor: Scaramuzzino, Giovanni AL LT LV MK RO SI 20052 Monza (Milano) (IT) (54) Nitrate prodrugs able to release nitric oxide in a controlled and selective way and their use for prevention and treatment of inflammatory, ischemic and proliferative diseases (57) New pharmaceutical compounds of general effects and for this reason they are useful for the prep- formula (I): F-(X)q where q is an integer from 1 to 5, pref- aration of medicines for prevention and treatment of in- erably 1; -F is chosen among drugs described in the text, flammatory, ischemic, degenerative and proliferative -X is chosen among 4 groups -M, -T, -V and -Y as de- diseases of musculoskeletal, tegumental, respiratory, scribed in the text. gastrointestinal, genito-urinary and central nervous sys- The compounds of general formula (I) are nitrate tems. prodrugs which can release nitric oxide in vivo in a con- trolled and selective way and without hypotensive side EP 1 336 602 A1 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 1 336 602 A1 Description [0001] The present invention relates to new nitrate prodrugs which can release nitric oxide in vivo in a controlled and selective way and without the side effects typical of nitrate vasodilators drugs. -

Intramuscular Tramadol Vs. Diclofenac Sodium for The

J Headache Pain (2005) 6:143–148 DOI 10.1007/s10194-005-0169-y ORIGINAL Zulfi Engindeniz Intramuscular tramadol vs. diclofenac sodium Celaleddin Demircan Necdet Karli for the treatment of acute migraine attacks Erol Armagan in emergency department: a prospective, Mehtap Bulut Tayfun Aydin randomised, double-blind study Mehmet Zarifoglu Received: 6 February 2005 Abstract The aim of this prospec- injection in future visits. Any Accepted in revised form: 15 April 2005 tive, randomised, double-blind study adverse events, whether related to Published online: 13 May 2005 was to evaluate the efficacy of intra- the drug or not, were also recorded. muscular (IM) tramadol 100 mg in Patients were followed up by tele- emergency department treatment of phone 48 h later to check for any acute migraine attack and to com- headache recurrence. Two-hour pain pare it with that of IM diclofenac response rate, which was the prima- sodium 75 mg. Forty patients who ry endpoint, was 80% for both tra- were admitted to our emergency madol and diclofenac groups. There department with acute migraine were no statistically significant dif- attack according to the International ferences among groups in terms of Z. Engindeniz (౧) • E. Armagan • M. Bulut Headache Society criteria were 48-h pain response, rescue treat- T. Aydin Department of Emergency Medicine, included in the study. Patients were ment, associated symptoms’ Uludag University Medical Faculty, randomised to receive either tra- response, headache recurrence and Acil Tip ABD Gorukle, madol 100 mg (n=20) or diclofenac adverse event rates. Fifteen (75%) Bursa 16059, Turkey sodium 75 mg (n=20) intramuscular- patients in the tramadol group and e-mail: [email protected] ly. -

ERJ-01090-2018.Supplement

Shaheen et al Online data supplement Prescribed analgesics in pregnancy and risk of childhood asthma Seif O Shaheen, Cecilia Lundholm, Bronwyn K Brew, Catarina Almqvist. 1 Shaheen et al Figure E1: Data available for analysis Footnote: Numbers refer to adjusted analyses (complete data on covariates) 2 Shaheen et al Table E1. Three classes of analgesics included in the analyses ATC codes Generic drug name Opioids N02AA59 Codeine, combinations excluding psycholeptics N02AA79 Codeine, combinations with psycholeptics N02AA08 Dihydrocodeine N02AA58 Dihydrocodeine, combinations N02AC04 Dextropropoxyphene N02AC54 Dextropropoxyphene, combinations excluding psycholeptics N02AX02 Tramadol Anti-migraine N02CA01 Dihydroergotamine N02CA02 Ergotamine N02CA04 Methysergide N02CA07 Lisuride N02CA51 Dihydroergotamine, combinations N02CA52 Ergotamine, combinations excluding psycholeptics N02CA72 Ergotamine, combinations with psycholeptics N02CC01 Sumatriptan N02CC02 Naratriptan N02CC03 Zolmitriptan N02CC04 Rizatriptan N02CC05 Almotriptan N02CC06 Eletriptan N02CC07 Frovatriptan N02CX01 Pizotifen N02CX02 Clonidine N02CX03 Iprazochrome N02CX05 Dimetotiazine N02CX06 Oxetorone N02CB01 Flumedroxone Paracetamol N02BE01 Paracetamol N02BE51 Paracetamol, combinations excluding psycholeptics N02BE71 Paracetamol, combinations with psycholeptics 3 Shaheen et al Table E2. Frequency of analgesic classes prescribed to the mother during pregnancy Opioids Anti- Paracetamol N % migraine No No No 459,690 93.2 No No Yes 9,091 1.8 Yes No No 15,405 3.1 No Yes No 2,343 0.5 Yes No -

The Serotonergic System in Migraine Andrea Rigamonti Domenico D’Amico Licia Grazzi Susanna Usai Gennaro Bussone

J Headache Pain (2001) 2:S43–S46 © Springer-Verlag 2001 MIGRAINE AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY Massimo Leone The serotonergic system in migraine Andrea Rigamonti Domenico D’Amico Licia Grazzi Susanna Usai Gennaro Bussone Abstract Serotonin (5-HT) and induce migraine attacks. Moreover serotonin receptors play an impor- different pharmacological preventive tant role in migraine pathophysiolo- therapies (pizotifen, cyproheptadine gy. Changes in platelet 5-HT content and methysergide) are antagonist of are not casually related, but they the same receptor class. On the other may reflect similar changes at a neu- side the activation of 5-HT1B-1D ronal level. Seven different classes receptors (triptans and ergotamines) of serotoninergic receptors are induce a vasocostriction, a block of known, nevertheless only 5-HT2B-2C neurogenic inflammation and pain M. Leone • A. Rigamonti • D. D’Amico and 5HT1B-1D are related to migraine transmission. L. Grazzi • S. Usai • G. Bussone (౧) syndrome. Pharmacological evi- C. Besta National Neurological Institute, Via Celoria 11, I-20133 Milan, Italy dences suggest that migraine is due Key words Serotonin • Migraine • e-mail: [email protected] to an hypersensitivity of 5-HT2B-2C Triptans • m-Chlorophenylpiperazine • Tel.: +39-02-2394264 receptors. m-Chlorophenylpiperazine Pathogenesis Fax: +39-02-70638067 (mCPP), a 5-HT2B-2C agonist, may The 5-HT receptor family is distinguished from all other 5- Introduction 1 HT receptors by the absence of introns in the genes; in addi- tion all are inhibitors of adenylate cyclase [1]. Serotonin (5-HT) and serotonin receptors play an important The 5-HT1A receptor has a high selective affinity for 8- role in migraine pathophysiology. -

Antimigraine Agents, Triptans Review 07/21/2008

Antimigraine Agents, Triptans Review 07/21/2008 Copyright © 2004 - 2008 by Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or via any information storage and retrieval system without the express written consent of Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All requests for permission should be mailed to: Attention: Copyright Administrator Intellectual Property Department Provider Synergies, L.L.C. 5181 Natorp Blvd., Suite 205 Mason, Ohio 45040 The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the collective authors and editors and should not be construed to be the official representation of any professional organization or group, any state Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee, any state Medicaid Agency, or any other clinical committee. This material is not intended to be relied upon as medical advice for specific medical cases and nothing contained herein should be relied upon by any patient, medical professional or layperson seeking information about a specific course of treatment for a specific medical condition. All readers of this material are responsible for independently obtaining medical advice and guidance from their own physician and/or other medical professional in regard to the best course of treatment for their specific medical condition. This publication, inclusive of all forms contained herein, is intended -

Frovatriptan Versus Zolmitriptan for the Acute Treatment of Migraine: a Double-Blind, Randomized, Multicenter, Italian Study

Neurol Sci (2010) 31 (Suppl 1):S51–S54 DOI 10.1007/s10072-010-0273-x SYMPOSIUM: NEWS IN TREATMENT OF MIGRAINE ATTACK Frovatriptan versus zolmitriptan for the acute treatment of migraine: a double-blind, randomized, multicenter, Italian study Vincenzo Tullo • Gianni Allais • Michel D. Ferrari • Marcella Curone • Eliana Mea • Stefano Omboni • Chiara Benedetto • Dario Zava • Gennaro Bussone Ó The Author(s) 2010. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The objective of this study is to assess patients’ of PF episodes at 2 h was 26% with F and 31% with Z satisfaction with migraine treatment with frovatriptan (F) (p = NS). PR episodes at 2 h were 57% for F and 58% for or zolmitriptan (Z), by preference questionnaire. 133 sub- Z(p = NS). Rate of recurrence was 21 (F) and 24% jects with a history of migraine with or without aura (IHS (Z; p = NS). Time to recurrence within 48 h was better for criteria) were randomized to F 2.5 mg or Z 2.5 mg. The F especially between 4 and 16 h (p \ 0.05). SPF episodes study had a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, cross- were 18 (F) versus 22% (Z; p = NS). Drug-related adverse over design, with each of the two treatment periods lasting events were significantly (p \ 0.05) less under F (3 vs. 10). no more than 3 months. At the end of the study, patients In conclusion, our study suggests that F has a similar were asked to assign preference to one of the treatments efficacy of Z, with some advantage as regards tolerability (primary endpoint). -

Pizotifen Activates ERK and Provides Neuroprotection in Vitro and in Vivo in Models of Huntington’S Disease

Journal of Huntington’s Disease 1 (2012) 195–210 195 DOI 10.3233/JHD-120033 IOS Press Research Report Pizotifen Activates ERK and Provides Neuroprotection in vitro and in vivo in Models of Huntington’s Disease Melissa R. Sarantos1, Theodora Papanikolaou1, Lisa M. Ellerby∗ and Robert E. Hughes∗ The Buck Institute for Research on Aging, Novato, CA, USA Abstract. Background: Huntington’s disease (HD) is a dominantly inherited neurodegenerative condition characterized by dysfunction in striatal and cortical neurons. There are currently no approved drugs known to slow the progression of HD. Objective: To facilitate the development of therapies for HD, we identified approved drugs that can ameliorate mutant huntingtin- induced toxicity in experimental models of HD. Methods: A chemical screen was performed in a mouse HdhQ111/Q111 striatal cell model of HD. This screen identified a set of structurally related approved drugs (pizotifen, cyproheptadine, and loxapine) that rescued cell death in this model. Pizotifen was subsequently evaluated in the R6/2 HD mouse model. Results: We found that in striatal HdhQ111/Q111 cells, pizotifen treatment caused transient ERK activation and inhibition of ERK activation prevented rescue of cell death in this model. In the R6/2 HD mouse model, treatment with pizotifen activated ERK in the striatum, reduced neurodegeneration and significantly enhanced motor performance. Conclusions: These results suggest that pizotifen and related approved drugs may provide a basis for developing disease modifying therapeutic interventions for HD. Keywords: Huntington’s disease, Drug screening, Pizotifen, ERK Pathway, R6/2 HD mouse model ABBREVIATIONS of mutant huntingtin (Htt) protein containing an expanded polyglutamine tract. -

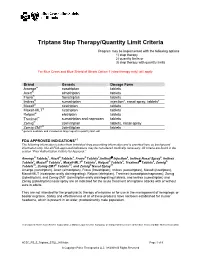

Triptans Step Therapy/Quantity Limit Criteria

Triptans Step Therapy/Quantity Limit Criteria Program may be implemented with the following options 1) step therapy 2) quantity limits or 3) step therapy with quantity limits For Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois Option 1 (step therapy only) will apply. Brand Generic Dosage Form Amerge® naratriptan tablets Axert® almotriptan tablets Frova® frovatriptan tablets Imitrex® sumatriptan injection*, nasal spray, tablets* Maxalt® rizatriptan tablets Maxalt-MLT® rizatriptan tablets Relpax® eletriptan tablets Treximet™ sumatriptan and naproxen tablets Zomig® zolmitriptan tablets, nasal spray Zomig-ZMT® zolmitriptan tablets * generic available and included as target agent in quantity limit edit FDA APPROVED INDICATIONS1-7 The following information is taken from individual drug prescribing information and is provided here as background information only. Not all FDA-approved indications may be considered medically necessary. All criteria are found in the section “Prior Authorization Criteria for Approval.” Amerge® Tablets1, Axert® Tablets2, Frova® Tablets3,Imitrex® injection4, Imitrex Nasal Spray5, Imitrex Tablets6, Maxalt® Tablets7, Maxalt-MLT® Tablets7, Relpax® Tablets8, Treximet™ Tablets9, Zomig® Tablets10, Zomig-ZMT® Tablets10, and Zomig® Nasal Spray11 Amerge (naratriptan), Axert (almotriptan), Frova (frovatriptan), Imitrex (sumatriptan), Maxalt (rizatriptan), Maxalt-MLT (rizatriptan orally disintegrating), Relpax (eletriptan), Treximet (sumatriptan/naproxen), Zomig (zolmitriptan), and Zomig-ZMT (zolmitriptan orally disintegrating) tablets, and Imitrex (sumatriptan) and Zomig (zolmitriptan) nasal spray are all indicated for the acute treatment of migraine attacks with or without aura in adults. They are not intended for the prophylactic therapy of migraine or for use in the management of hemiplegic or basilar migraine. Safety and effectiveness of all of these products have not been established for cluster headache, which is present in an older, predominantly male population. -

(DMT), Harmine, Harmaline and Tetrahydroharmine: Clinical and Forensic Impact

pharmaceuticals Review Toxicokinetics and Toxicodynamics of Ayahuasca Alkaloids N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), Harmine, Harmaline and Tetrahydroharmine: Clinical and Forensic Impact Andreia Machado Brito-da-Costa 1 , Diana Dias-da-Silva 1,2,* , Nelson G. M. Gomes 1,3 , Ricardo Jorge Dinis-Oliveira 1,2,4,* and Áurea Madureira-Carvalho 1,3 1 Department of Sciences, IINFACTS-Institute of Research and Advanced Training in Health Sciences and Technologies, University Institute of Health Sciences (IUCS), CESPU, CRL, 4585-116 Gandra, Portugal; [email protected] (A.M.B.-d.-C.); ngomes@ff.up.pt (N.G.M.G.); [email protected] (Á.M.-C.) 2 UCIBIO-REQUIMTE, Laboratory of Toxicology, Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Porto, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal 3 LAQV-REQUIMTE, Laboratory of Pharmacognosy, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Porto, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal 4 Department of Public Health and Forensic Sciences, and Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, 4200-319 Porto, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.D.-d.-S.); [email protected] (R.J.D.-O.); Tel.: +351-224-157-216 (R.J.D.-O.) Received: 21 September 2020; Accepted: 20 October 2020; Published: 23 October 2020 Abstract: Ayahuasca is a hallucinogenic botanical beverage originally used by indigenous Amazonian tribes in religious ceremonies and therapeutic practices. While ethnobotanical surveys still indicate its spiritual and medicinal uses, consumption of ayahuasca has been progressively related with a recreational purpose, particularly in Western societies. The ayahuasca aqueous concoction is typically prepared from the leaves of the N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT)-containing Psychotria viridis, and the stem and bark of Banisteriopsis caapi, the plant source of harmala alkaloids. -

Diapositiva 1

Characterization of the 5-HT7 receptor as a new therapeutic target for the treatment of pain Àlex Brenchat Barberà ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. -

Zomig and Zomig Rapimelt Are Trade Marks of the Astrazeneca Group of Companies

AUSTRALIAN PRODUCT INFORMATION Zomig® and Zomig Rapimelt® (zolmitriptan) 1 NAME OF THE MEDICINE Zolmitriptan 2 QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Zomig is presented as round, yellow (2.5 mg) or pink (5 mg), biconvex film-coated intagliated (with a ‘Z’ on one side) tablets containing 2.5 mg or 5 mg zolmitriptan. The 2.5 mg tablets are 7.4 mm in diameter and are compressed to a weight of 122 mg. The 5 mg tablets are 8.6 mm in diameter and are compressed to a weight of 244 mg. Zomig Rapimelt is presented as orally dispersible white round uncoated orange flavoured tablets containing 2.5 mg zolmitriptan. The tablets are 6.4 mm in diameter, flat-faced with a bevelled edge and intagliated with ‘Z’ on one side. The tablets are compressed to a weight of 100 mg. Excipient(s) with known effect: lactose monohydrate (Zomig), aspartame (Zomig Rapimelt). For the full list of excipients, see Section 6.1 List of excipients. 3 PHARMACEUTICAL FORM • Tablet, film-coated • Tablet, dispersible (oral) 4 CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 THERAPEUTIC INDICATIONS Zomig is indicated for the acute treatment of migraine with or without aura. 4.2 DOSE AND METHOD OF ADMINISTRATION The recommended initial dose of Zomig to treat a migraine attack is 2.5 mg. The Zomig conventional tablet should be swallowed whole with water. The Zomig Rapimelt orally dispersible tablet rapidly dissolves when placed on the tongue and is swallowed with the patient’s saliva. A drink of water is not required when taking the Zomig Rapimelt orally dispersible tablet. -

Daily Triptans for Headache

Expert Opinion Daily Triptans for Headache Case History Submitted by Randolph W. Evans, MD Expert Opinion by Lawrence Robbins, MD Key words: headache, triptans Abbreviations: CDH chronic daily headache (Headache 2001;41:907-909) Will a triptan a day keep the headache away? I advised the patient that the increased frequency of the headaches could be rebound due to sumatriptan CLINICAL HISTORY and that the headaches might decrease by restricting This 47-year-old woman has a history of migraine the sumatriptan to no more than 2 days per week and since aged 4 years. Until 1 year ago, the headaches oc- starting another preventative such as sodium valpro- curred one to two times per week, lasted all day, re- ate. She is concerned about the possible side effects sulted in functional incapacity, and were not relieved of sodium valproate, which she has read can make you by over-the-counter medications or nonsteroidal anti- fat and bald. She also stated that the headaches were inflammatory drugs. About 10 years ago, she was tak- quite tolerable with the daily sumatriptan and she ing Fiorinal #3 but stopped when she developed could not see the difference between taking daily rebound headaches. She has been on multiple preven- sumatriptan as compared to a preventative which may tative medications including amitriptyline, -blockers, or may not work and may have significant side effects. paroxetine, fluoxetine, and verapamil which were ei- Questions.—Is there evidence to support daily ther not effective or stopped due to side effects. triptan use for migraine? What would you recom- One year ago, she saw another neurologist and mend in this case? had an MRI scan of the brain with normal findings.