Epa 2020 Community Involvement Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C

REPORT NO. PN-1-210205-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/05/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000132840 Assignment AM WING 25039 Main 1410.0 DAYTON, OH ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession 0000132974 Assignment FM KKUU 11658 Main 92.7 INDIO, CA ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession 0000132926 Assignment AM WSGW 22674 Main 790.0 SAGINAW, MI ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession 0000132914 Assignment FM WDLD 23469 Main 96.7 HALFWAY, MD ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession 0000132842 Assignment AM WJQS 50409 Main 1400.0 JACKSON, MS ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession Page 1 of 66 REPORT NO. PN-1-210205-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/05/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. -

Alpha Media USA LLC ) FRN: 0025019530 ) Licensee of Various Commercial Radio Stations ) ) )

Federal Communications Commission DA 20-772 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of Online Political Files of ) File No.: MB/POL-07072020-A ) Alpha Media USA LLC ) FRN: 0025019530 ) Licensee of Various Commercial Radio Stations ) ) ) ORDER Adopted: July 22, 2020 Released: July 22, 2020 By the Chief, Media Bureau: 1. In this Order, we adopt the attached Consent Decree entered into between the Federal Communications Commission (the Commission) and Alpha Media USA LLC (Alpha Media). The Consent Decree resolves the Commission’s investigation into whether Alpha Media violated section 315(e)(3) of the Communications Act of 1934, as amended (the Act), and section 73.1943(c) of the Commission’s rules in connection with the timeliness of uploads of required information to the online political files of certain of its owned and operated radio stations. To resolve this matter, Alpha Media agrees, among other things, to implement a comprehensive Compliance Plan and to provide periodic Compliance Reports to the Bureau. 2. The Commission first adopted rules requiring broadcast stations to maintain public files documenting requests for political advertising time more than 80 years ago,1 and political file obligations have been embodied in section 315(e) of the Act since 2002.2 Section 315(e)(1) requires radio station licensees, among other regulatees, to maintain and make available for public inspection information about each request for the purchase of broadcast time that is made: (a) by or on behalf of a -

Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions Poster Sessions Continuing

Sessions and Events Day Thursday, January 21 (Sessions 1001 - 1025, 1467) Friday, January 22 (Sessions 1026 - 1049) Monday, January 25 (Sessions 1050 - 1061, 1063 - 1141) Wednesday, January 27 (Sessions 1062, 1171, 1255 - 1339) Tuesday, January 26 (Sessions 1142 - 1170, 1172 - 1254) Thursday, January 28 (Sessions 1340 - 1419) Friday, January 29 (Sessions 1420 - 1466) Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions More than 50 sessions and workshops will focus on the spotlight theme for the 2019 Annual Meeting: Transportation for a Smart, Sustainable, and Equitable Future . In addition, more than 170 sessions and workshops will look at one or more of the following hot topics identified by the TRB Executive Committee: Transformational Technologies: New technologies that have the potential to transform transportation as we know it. Resilience and Sustainability: How transportation agencies operate and manage systems that are economically stable, equitable to all users, and operated safely and securely during daily and disruptive events. Transportation and Public Health: Effects that transportation can have on public health by reducing transportation related casualties, providing easy access to healthcare services, mitigating environmental impacts, and reducing the transmission of communicable diseases. To find sessions on these topics, look for the Spotlight icon and the Hot Topic icon i n the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section beginning on page 37. Poster Sessions Convention Center, Lower Level, Hall A (new location this year) Poster Sessions provide an opportunity to interact with authors in a more personal setting than the conventional lecture. The papers presented in these sessions meet the same review criteria as lectern session presentations. For a complete list of poster sessions, see the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section, beginning on page 37. -

Stability of a Flapping Wing Micro Air Vehicle

Stability of a Flapping Wing Micro Air Vehicle Marc Evan MacMaster A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Applied Science Graduate Department of Aerospace Science and Engineering University of Toronto 0 Copynpynghtby Marc MacMaster 2001 Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibbgraphic Se~ices seMeas bibliographiques The author has grauteci a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive Licence aiiowing the exclusive permettant à la National Li- of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seii reproduire, prêter, distriiuer ou copies of this thesis m microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous papa or ekcîronic fomats. Ia forme de microfichelf;ilm,de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownershfp of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auîeur qai protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantid extracts tiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othewise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the anthor's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Stability of a Flapping Wing Micro Air Vehicle Masters of Appiied Science, 2001 Marc Evan MacMaster Graduate Department of Aerospace Saence and Engineering University of Toronto Abstract An experimental investigation into the stabiiii of a flappiug wing micro air vehicle was perfomied at the University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies. A thtee-degree of Wom force balance was designed and constnicted to measure the forces and moments exhibiteci by a set of flapping wings through 180' of rotation at varied fiee-stream velocities. -

Wing Installation Instructions

Sonex Aircraft, LLC PO Box 2521 Oshkosh, WI 54903-2521 (920) 231-8297 Fax: 920-426-8333 www.SonexAircraft.com ________________________________________________________________________ WING INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS 032706 Wing Installation Instructions Step 1: Preparation: Lay wings on each side of the fuselage, Lubricate the root tangs with WD40, Remove Bottom Seat Cushion. Step 2: With one person at the root and the other at the tip, pick up the wing panel. Step 3: Slide the right wing spar partially into the fuselage. Support the flap so the linkage does not jam. Check the pitot lines and aileron pushrod for proper position and then continue to push the wing into the spar box, carefully engaging the rear spar. Step 4: While looking at the spar position in the left side of the spar tunnel, raise or lower the wingtip until the spar pin holes are aligned. Step 5: Insert spar pins halfway into the right spar. Step 6: Slide left wing partially into the spar tunnel. Step 7: Check the aileron pushrod for proper position and then continue to push the wing into the spar box, carefully engaging the rear spar. Step 8: Push the spar pins into place. Step 9: Raise or lower the rear spar to align the holes and install the pins. Step 10: Insert all four safety pins in the spar pins. Step 11: With the flaps supported, connect and safety the flap pushrods. Step 12: Attach the aileron pushrods. Step 13: Connect the pitot lines at the wing root. Step 14: Connect the pitot lines at the pitot tube and check for leaks. -

The Role of the Intensive Care Unit Environment in the Pathogenesis and Prevention of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

The Role of the Intensive Care Unit Environment in the Pathogenesis and Prevention of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia Christopher J Crnich MD MSc, Nasia Safdar MD MSc, and Dennis G Maki MD Introduction Epidemiology and Pathogenesis Aerodigestive Colonization Direct Inoculation of the Lower Airway Importance of Endogenous Versus Exogenous Colonization Environmental Sources of Colonization Animate Environment Inanimate Environment The Need for a More Comprehensive Approach to the Prevention of VAP That Acknowledges the Important Role of the Hospital Environment Organizational Structure Interventions at the Interface Between the Health Care Worker and the Patient or Inanimate Environment Prevention of Infections Caused by Respiratory Devices Prevention of Infections Caused by Legionella Species Prevention of Infections Caused by Filamentous Fungi Summary Ventilator-associated pneumonia is preceded by lower-respiratory-tract colonization by pathogenic microorganisms that derive from endogenous or exogenous sources. Most ventilator-associated pneumonias are the result of exogenous nosocomial colonization, especially, pneumonias caused by resistant bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and multi-resistant Acineto- bacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa,orbyLegionella species or filamentous fungi, such as Aspergillus. Exogenous colonization originates from a very wide variety of animate and inani- mate sources in the intensive care unit environment. As a result, a strategic approach that combines measures to prevent cross-colonization with those that focus on oral hygiene and prevention of microaspiration of colonized oropharyngeal secretions should bring the greatest reduction in the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia. This review examines strategies to prevent transmission of environmental pathogens to the vulnerable mechanically-ventilated patient. Key words: ventilator- associated pneumonia. [Respir Care 2005;50(6):813–836. -

UTSA Roadrunners

UTSA R O A D ru NNE rs BASKETBALL 2012-13 MEN’S BasKEtbaLL MEDIA SUPPLEMENT T ABLE OF C ON T EN T S MEDIA INFORMATION OPPONENTS Season Outlook ___________________________________2-3 Opponents Quick Facts _________________________ 32-34 Roster ____________________________________________ 4 Western Athletic Conference Tournament _____________ 35 Schedule __________________________________________ 5 Western Athletic Conference ________________________ 36 Media Information _________________________________ 6 Broadcast Information_______________________________ 7 SEASON REVIEW Quick Facts _______________________________________ 7 Schedule/Results __________________________________ 38 goUTSA.com ______________________________________ 8 Season Box Score _________________________________ 39 Team Statistics ____________________________________ 39 MEET THE ROADRUNNERS Attendance Summary ______________________________ 39 Kannon Burrage __________________________________ 10 Game-by-Game Statistics ___________________________ 40 Michael Hale III ___________________________________ 11 Superlatives ______________________________________ 41 Larry Wilkins _____________________________________ 12 Game Capsules ________________________________ 42-47 Jeromie HIll _______________________________________ 13 Starters Summary _________________________________ 47 Jordan Sims ______________________________________ 14 Southland Conference Review _______________________ 48 Tyler Wood _______________________________________ 15 Devon Agusi______________________________________ -

Public Comment Response Report

Public Comment Response Report December 1993 GOV^ ENTS 1S94 THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS Low-Level Radioactive Waste Management Board Department of Public Health Department of Environmental Protection Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/publicconinientresOOmass Public Comment Response Report December 1993 THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS Low-Level Radioactive Waste Management Board Department of Public Health Department of Environmental Protection Publication No. 17488 - 165 - 1400 - 1/94 - 4.00 - C. R. printed on recycled paper Approved by; Philmore Anderson III, State Purchasing Agent Table of Contents Page Introduction 1 Overall Summary 5 Comments on VOLUME I of the Draft Low-Level Radioactive Waste Management Plan (with responses) 11 Comments on VOLUME 11 of the Draft Low-Level Radioactive Waste Management Plan (with responses) 21 Comments on the Draft LLRW Facility Operator Selection Regulations (345 CMR 3.00) (with responses) 115 Comments on the Draft Department of Public Health Licensing and Op)erational Regulations for LLRW Facilities (Part M - 105 CMR 120.800) and LLRW Minimization Regulations (Part Ml - 105 CMR 120.890) (with responses) 119 Comments on the Draft Department of Environmental Protection LLRW Facility Site Selection Criteria regulations (310 CMR 41.00) (with responses) 137 List of Commenters 1 47 Introduction This Public Comment Response Report summarizes the comments received on draft documents relating to the management of low-level radioactive waste (LLRW) in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The -- documents were issued January 21 , 1993. by three state government agencies the Low-Level Radioactive Waste Management Board (a nine-member board appointed by the Governor), the Department of Public Health (DPH), and the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) - in accordance with Massachusetts General Laws Chapter 1 1 1 H, the Massachusetts Low-Level Radioactive Waste Management Act (referenced throughout this report as "Chapter 111H"). -

State of Ohio Emergency Alert System Plan

STATE OF OHIO EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM PLAN SEPTEMBER 2003 ASHTABULA CENTRAL AND LAKE LUCAS FULTON WILLIAMS OTTAWA EAST LAKESHORE GEAUGA NORTHWEST CUYAHOGA SANDUSKY DEFIANCE ERIE TRUMBULL HENRY WOOD LORAIN PORTAGE YOUNGSTOWN SUMMIT HURON MEDINA PAULDING SENECA PUTNAM MAHONING HANCOCK LIMA CRAWFORD ASHLAND VAN WERT WYANDOT WAYNE STARK COLUMBIANA NORTH RICHLAND ALLEN EAST CENTRAL ‘ HARDIN CENTRAL CARROLL HOLMES MERCER MARION AUGLAIZE MORROW JEFFERSON TUSCARAWAS KNOX LOGAN COSHOCTON SHELBY UNION HARRISON DELAWARE DARKE CHAMPAIGN LICKING GUERNSEY BELMONT MIAMI MUSKINGUM WEST CENTRAL FRANKLIN CLARK CENTRAL MONTGOMERY UPPER OHIO VALLEY MADISON PERRY NOBLE MONROE PREBLE FAIRFIELD GREENE PICKAWAY MORGAN FAYETTE HOCKING WASHINGTON BUTLER WARREN CLINTON ATHENS SOUTHWEST ROSS VINTON HAMILTON HIGHLAND SOUTHEAST MEIGS CLERMONT SOUTH CENTRAL PIKE JACKSON GALLIA BROWN ADAMS SCIOTO LAWRENCE Ohio Emergency Management Agency (EMA) (20) All Ohio County EMA Directors NWS Wilmington, OH NWS Cleveland, OH NWS Pittsburgh, PA NWS Charleston, WV NWS Fort Wayne, IN NWS Grand Rapids, MI All Ohio Radio and TV Stations All Ohio Cable Systems WOVK Radio, West Virginia Ohio Association of Broadcasters (OAB) Ohio SECC Chairman All Operational Area LECC Chairmen All Operational Area LECC Vice Chairmen Ohio SECC Cable Co-Chairman All Ohio County Sheriffs President, All County Commissioners Ohio Educational Telecommunications Network Commission (OET) Ohio Cable Telecommunications Association (OCTA) Michigan Emergency Management Agency Michigan SECC Chairman Indiana Emergency Management Agency Indiana SECC Chairman Kentucky Emergency Management Agency Kentucky SECC Chairman Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency Pennsylvania SECC Chairman West Virginia Emergency Management Agency West Virginia SECC Chairman Additional copies are available from: Ohio Emergency Management Agency 2855 West Dublin Granville Road Columbus, Ohio 43235-2206 (614) 889-7150 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. -

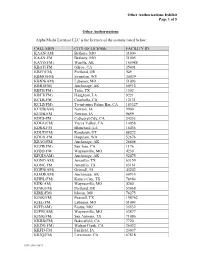

Alpha Assignees Other Authorizations Exhibit.Pdf

Other Authorizations Exhibit Page 1 of 5 Other Authorizations Alpha Media Licensee LLC is the licensee of the stations listed below: CALL SIGN CITY OF LICENSE FACILITY ID KAAN(AM) Bethany, MO 31004 KAAN-FM Bethany, MO 31005 KAYO(FM) Wasilla, AK 165988 KBAY(FM) Gilroy, CA 35401 KBFF(FM) Portland, OR 949 KBMG(FM) Evanston, WY 20029 KBNN(AM) Lebanon, MO 51093 KBRJ(FM) Anchorage, AK 60915 KBTE(FM) Tulia, TX 1302 KBTT(FM) Haughton, LA 9221 KCLB-FM Coachella, CA 12131 KCLZ(FM) Twentynine Palms Bas, CA 183327 KCOB(AM) Newton, IA 9900 KCOB-FM Newton, IA 9899 KDES-FM Cathedral City, CA 24253 KDGL(FM) Yucca Valley, CA 14058 KDKS-FM Blanchard, LA 16436 KDUT(FM) Randolph, UT 88272 KDUX-FM Hoquiam, WA 52676 KEAG(FM) Anchorage, AK 28648 KEZR(FM) San Jose, CA 1176 KFBD-FM Waynesville, MO 4259 KFQD(AM) Anchorage, AK 52675 KGNC(AM) Amarillo, TX 63159 KGNC-FM Amarillo, TX 63161 KGRN(AM) Grinnell, IA 43242 KHAR(AM) Anchorage, AK 60914 KHHL(FM) Karnes City, TX 78984 KIIK(AM) Waynesville, MO 4260 KINK(FM) Portland, OR 53068 KIRK(FM) Macon, MO 78275 KJAK(FM) Pearsall, TX 198762 KJEL(FM) Lebanon, MO 51094 KJFF(AM) Festus, MO 35532 KJPW(AM) Waynesville, MO 53877 KJXK(FM) San Antonio, TX 71086 KKBB(FM) Bakersfield, CA 7720 KKDV(FM) Walnut Creek, CA 36032 KKFD-FM Fairfield, IA 23037 KKIQ(FM) Livermore, CA 67818 4843-2998-3967.1 Other Authorizations Exhibit Page 2 of 5 CALL SIGN CITY OF LICENSE FACILITY ID KKRT(AM) Wenatchee, WA 28634 KKRV(FM) Wenatchee, WA 28635 KKUS(FM) Tyler, TX 68651 KKUU(FM) Indio, CA 11658 KKWK(FM) Cameron, MO 50745 KLAK(FM) Tom Bean, TX -

West Central Ohio Emergency Alert System

WEST CENTRAL OHIO EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM OPERATIONAL AREA PLAN ASHTABULA LAKE LUCAS FULTON WILLIAMS OTTAWA GEAUGA CUYAHOGA DEFIANCE SANDUSKY ERIE TRUMBULL HENRY WOOD LORAIN PORTAGE SUMMIT HURON MEDINA PAULDING SENECA PUTNAM MAHONING HANCOCK ASHLAND VAN WERT WYANDOT CRAWFORD WAYNE STARK COLUMBIANA ALLEN RICHLAND ‘ HARDIN CARROLL MERCER MARION HOLMES AUGLAIZE MORROW JEFFERSON TUSCARAWAS KNOX LOGAN COSHOCTON SHELBY UNION HARRISON DELAWARE DARKE LICKING CHAMPAIGN GUERNSEY MIAMI MUSKINGUM BELMONT FRANKLIN CLARK MONTGOMERY MADISON PERRY NOBLE MONROE PREBLE GREENEGREENE FAIRFIELD PICKAWAY MORGAN FAYETTE HOCKING WASHINGTON BUTLER WARREN CLINTON ATHENS ROSS VINTON HAMILTON HIGHLAND MEIGS CLERMONT PIKE JACKSON GALLIA BROWN ADAMS SCIOTO LOGAN SHELBY LAWRENCE DARKE CHAMPAIGN MIAMI CLARK MONTGOMERY PREBLE GREENE EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM WEST CENTRAL OHIO OPERATIONAL AREA PLAN AND PROCEDURES FOR THE FOLLOWING OHIO COUNTIES CHAMPAIGN CLARK DARKE GREENE LOGAN MIAMI MONTGOMERY PREBLE SHELBY Revised January 2005 DISTRIBUTION: Ohio Emergency Management Agency (EMA) (20) All West Central Ohio Operational Area County EMA Directors All West Central Ohio Operational Area County Sheriffs Miami County 911 Coordinator All EAS West Central Ohio Operational Area Radio and TV Stations All West Central Ohio Cable TV Systems Ohio SECC Chairman Ohio SECC Cable Co-Chairman Local Area LECC Chairman Local Area LECC Vice Chairman Federal Communications Commission (FCC) National Weather Service - Wilmington Ohio Educational Telecommunications Network Commission (OET) Ohio Cable Telecommunications Association (OCTA) Ohio Association of Broadcasters (OAB) Indiana SECC Indiana Emergency Management Agency Jay County, Indiana, Emergency Management Agency Randolph County, Indiana, Emergency Management Agency Union County, Indiana, Emergency Management Agency Wayne County, Indiana, Emergency Management Agency Additional copies are available from: Ohio Emergency Management Agency 2855 West Dublin Granville Road Columbus, Ohio 43235-2206 (614) 889-7150 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. -

The Hilltop 9-12-2005

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University The iH lltop: 2000 - 2010 The iH lltop Digital Archive 9-12-2005 The iH lltop 9-12-2005 Hilltop Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_0010 Recommended Citation Staff, Hilltop, "The iH lltop 9-12-2005" (2005). The Hilltop: 2000 - 2010. 250. https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_0010/250 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The iH lltop Digital Archive at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH lltop: 2000 - 2010 by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .................................._...._ .................. __ .._. __ ._. __ .._ ..... _.._..~--~~~~~~--~~~ -:--~~~~--------- -- - - - ----------- - - -- -- w --- - r- --- ·-~-------- ------------- • • The Daily Student Voice of Howard University . - - - -- .. - : . -- ~ . - VOLUME 89, NO. 12 MONDAY, SEPTEMB~R 12, 2005 WWW.THEHILLTOPONLINE.COM MONDAY NOf EJOOK Feelings of Fear Four fears Later CAMPUS HU Students Still Afraid Years After 9111 MAKING A MILESTONE WHBC IS CELEBRATING THEIR 30TH ANNIVER SARY. FIND OUT WHAT THEY HAVE PLANNED FOR THIS MAJOR ACCOMPLISH MENT. PAGE 2 NATION & WORLD NOT GIVING PRAISE TOTIIELORD FIND OUT WHY SO MANY PREACHERS SAY THERE AREN'T ENOUGH BLACK MEN IN THE CHURCH. PAGE4 LIFE & SrYLE A MOUTH TO DIE FOR FIND OUT HOW TO MAKE YOUR CROOKED SMILE LOOKK DAZZLING WHITE. Sunday marked the four year annlvtr1ary 1lnct th• terrorllt attack• of Stpt1mb1r 11, 2001. De1plt• bllllon1 of dollar• 1pent by Con;rt11 to 11cur1 th1 homo PAGES land, poll• 1how that many Am1rlcnn1 do not foel any 11f1r today and fear 1noth1r t1rrorl1t attack.