Examining the Trump Administration's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STANDING COMMITTEES of the HOUSE Agriculture

STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE [Democrats in roman; Republicans in italic; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface] [Room numbers beginning with H are in the Capitol, with CHOB in the Cannon House Office Building, with LHOB in the Longworth House Office Building, with RHOB in the Rayburn House Office Building, with H1 in O’Neill House Office Building, and with H2 in the Ford House Office Building] Agriculture 1301 Longworth House Office Building, phone 225–2171, fax 225–8510 http://agriculture.house.gov meets first Wednesday of each month Collin C. Peterson, of Minnesota, Chair Tim Holden, of Pennsylvania. Bob Goodlatte, of Virginia. Mike McIntyre, of North Carolina. Terry Everett, of Alabama. Bob Etheridge, of North Carolina. Frank D. Lucas, of Oklahoma. Leonard L. Boswell, of Iowa. Jerry Moran, of Kansas. Joe Baca, of California. Robin Hayes, of North Carolina. Dennis A. Cardoza, of California. Timothy V. Johnson, of Illinois. David Scott, of Georgia. Sam Graves, of Missouri. Jim Marshall, of Georgia. Jo Bonner, of Alabama. Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, of South Dakota. Mike Rogers, of Alabama. Henry Cuellar, of Texas. Steve King, of Iowa. Jim Costa, of California. Marilyn N. Musgrave, of Colorado. John T. Salazar, of Colorado. Randy Neugebauer, of Texas. Brad Ellsworth, of Indiana. Charles W. Boustany, Jr., of Louisiana. Nancy E. Boyda, of Kansas. John R. ‘‘Randy’’ Kuhl, Jr., of New York. Zachary T. Space, of Ohio. Virginia Foxx, of North Carolina. Timothy J. Walz, of Minnesota. K. Michael Conaway, of Texas. Kirsten E. Gillibrand, of New York. Jeff Fortenberry, of Nebraska. Steve Kagen, of Wisconsin. Jean Schmidt, of Ohio. -

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Updated January 25, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL30857 Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Summary Each new House elects a Speaker by roll call vote when it first convenes. Customarily, the conference of each major party nominates a candidate whose name is placed in nomination. A Member normally votes for the candidate of his or her own party conference but may vote for any individual, whether nominated or not. To be elected, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of all the votes cast for individuals. This number may be less than a majority (now 218) of the full membership of the House because of vacancies, absentees, or Members answering “present.” This report provides data on elections of the Speaker in each Congress since 1913, when the House first reached its present size of 435 Members. During that period (63rd through 117th Congresses), a Speaker was elected six times with the votes of less than a majority of the full membership. If a Speaker dies or resigns during a Congress, the House immediately elects a new one. Five such elections occurred since 1913. In the earlier two cases, the House elected the new Speaker by resolution; in the more recent three, the body used the same procedure as at the outset of a Congress. If no candidate receives the requisite majority, the roll call is repeated until a Speaker is elected. Since 1913, this procedure has been necessary only in 1923, when nine ballots were required before a Speaker was elected. -

May 20, 2020 the Honorable Mitch Mcconnell the Honorable Nancy Pelosi S-230, the Capitol Main Office Washington, DC

The Honorable Kay Ivey, Governor of Alabama (Chair) The Honorable Mike Dunleavy, Governor of Alaska (Vice Chair) The Honorable Greg Abbott, Governor of Texas The Honorable Tate Reeves, Governor of Mississippi The Honorable John Bel Edwards, Governor of Louisiana May 20, 2020 The Honorable Mitch McConnell The Honorable Nancy Pelosi S-230, The Capitol Main Office Washington, DC 20510 H-232, The Capitol Washington, DC 20515 The Honorable John Thune The Honorable Steny Hoyer S-208, The Capitol H-107, The Capitol Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20515 The Honorable Charles E. Schumer The Honorable Kevin McCarthy S-221, The Capitol H-204, The Capitol Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, DC 20515 The Honorable Richard J. Durbin The Honorable Steve Scalise S-321, The Capitol H-148, The Capitol Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20515 Dear Senate and House Leaders: As our states and the nation continue to grapple with the economic and health impacts from the COVID-19 virus, it is more crucial than ever to continue to find ways to stimulate our respective economies and provide relief for our families and businesses. Further, it is vital that we continue to supply the country with energy to meet our critical needs. To help achieve these critical goals, the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Governors Coalition offers its continued support for efforts to increase revenue sharing to support coastal states responsible for energy production on the OCS. The Coalition urges you to consider the impacted coastal resources in these states and to include these needs in additional stimulus legislative relief and recovery packages. -

Newly Elected Representatives in the 114Th Congress

Newly Elected Representatives in the 114th Congress Contents Representative Gary Palmer (Alabama-6) ....................................................................................................... 3 Representative Ruben Gallego (Arizona-7) ...................................................................................................... 4 Representative J. French Hill (Arkansas-2) ...................................................................................................... 5 Representative Bruce Westerman (Arkansas-4) .............................................................................................. 6 Representative Mark DeSaulnier (California-11) ............................................................................................. 7 Representative Steve Knight (California-25) .................................................................................................... 8 Representative Peter Aguilar (California-31) ................................................................................................... 9 Representative Ted Lieu (California-33) ........................................................................................................ 10 Representative Norma Torres (California-35) ................................................................................................ 11 Representative Mimi Walters (California-45) ................................................................................................ 12 Representative Ken Buck (Colorado-4) ......................................................................................................... -

May 13, 2021 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker of the House H-232

May 13, 2021 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker of the House H-232 The Capitol Washington, DC 20515 Speaker Pelosi, In accordance with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance released on May 13, 2021 we urge you to immediately return to normal voting procedures and end mandatory mask requirements in the House of Representatives. CDC guidance states fully vaccinated people no longer need to wear a mask or physically distance in any setting except where required by governmental or workplace mandate. It is time to update our own workplace regulations. Every member of Congress has had the opportunity to be vaccinated, and you have indicated about 75 percent have taken advantage of this opportunity. The United States Congress must serve as a model to show the country we can resume normal life through vaccination. Let’s follow the science and get back to work. Sincerely, Bob Gibbs Member of Congress Lisa McClain Nancy Mace Member of Congress Member of Congress Jeff Duncan Ashley Hinson Member of Congress Member of Congress Robert E. Latta Barry Moore Member of Congress Member of Congress Ann Wagner Lauren Boebert Member of Congress Member of Congress Dusty Johnson Guy Reschenthaler Member of Congress Member of Congress Larry Bucshon Ronny Jackson Member of Congress Member of Congress Austin Scott Dan Newhouse Member of Congress Member of Congress Ralph Norman Ted Budd Member of Congress Member of Congress Mike Bost Beth Van Duyne Member of Congress Member of Congress Cliff Bentz Barry Loudermilk Member of Congress Member of Congress Dan Bishop Russ Fulcher Member of Congress Member of Congress Brian Mast Louie Gohmert Member of Congress Member of Congress Troy Balderson Warren Davidson Member of Congress Member of Congress Mary Miller Jerry Carl Member of Congress Member of Congress Jody Hice Ken Buck Member of Congress Member of Congress Bruce Westerman James R. -

Congress of the United States

Congress of the United States Washington, DC 20510 June 16, 2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW Washington, D.C. 20554 Dear Commissioners: On behalf of our constituents, we write to thank you for the Federal Communications Commission’s (Commission’s) efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic. The work the Commission has done, including the Keep Americans Connected pledge and the COVID-19 Telehealth Program, are important steps to address the need for connectivity as people are now required to learn, work, and access healthcare remotely. In addition to these efforts, we urge you to continue the important, ongoing work to close the digital divide through all means available, including by finalizing rules to enable the nationwide use of television white spaces (TVWS). The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the consequences of the remaining digital divide: many Americans in urban, suburban, and rural areas still lack access to a reliable internet connection when they need it most. Even before the pandemic broadband access challenges have put many of our constituents at a disadvantage for education, work, and healthcare. Stay-at-home orders and enforced social distancing intensify both the problems they face and the need for cost- effective broadband delivery models. The unique characteristics of TVWS spectrum make this technology an important tool for bridging the digital divide. It allows for better coverage with signals traveling further, penetrating trees and mountains better than other spectrum bands. Under your leadership, the FCC has taken significant bipartisan steps toward enabling the nationwide deployment of TVWS, including by unanimously adopting the February 2020 notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM), which makes several proposals that we support. -

August 10, 2021 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi the Honorable Steny

August 10, 2021 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Steny Hoyer Speaker Majority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader Hoyer, As we advance legislation to rebuild and renew America’s infrastructure, we encourage you to continue your commitment to combating the climate crisis by including critical clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation tax incentives in the upcoming infrastructure package. These incentives will play a critical role in America’s economic recovery, alleviate some of the pollution impacts that have been borne by disadvantaged communities, and help the country build back better and cleaner. The clean energy sector was projected to add 175,000 jobs in 2020 but the COVID-19 pandemic upended the industry and roughly 300,000 clean energy workers were still out of work in the beginning of 2021.1 Clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation tax incentives are an important part of bringing these workers back. It is critical that these policies support strong labor standards and domestic manufacturing. The importance of clean energy tax policy is made even more apparent and urgent with record- high temperatures in the Pacific Northwest, unprecedented drought across the West, and the impacts of tropical storms felt up and down the East Coast. We ask that the infrastructure package prioritize inclusion of a stable, predictable, and long-term tax platform that: Provides long-term extensions and expansions to the Production Tax Credit and Investment Tax Credit to meet President Biden’s goal of a carbon pollution-free power sector by 2035; Extends and modernizes tax incentives for commercial and residential energy efficiency improvements and residential electrification; Extends and modifies incentives for clean transportation options and alternative fuel infrastructure; and Supports domestic clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation manufacturing. -

Capitol Insurrection at Center of Conservative Movement

Capitol Insurrection At Center Of Conservative Movement: At Least 43 Governors, Senators And Members Of Congress Have Ties To Groups That Planned January 6th Rally And Riots. SUMMARY: On January 6, 2021, a rally in support of overturning the results of the 2020 presidential election “turned deadly” when thousands of people stormed the U.S. Capitol at Donald Trump’s urging. Even Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell, who rarely broke with Trump, has explicitly said, “the mob was fed lies. They were provoked by the President and other powerful people.” These “other powerful people” include a vast array of conservative officials and Trump allies who perpetuated false claims of fraud in the 2020 election after enjoying critical support from the groups that fueled the Capitol riot. In fact, at least 43 current Governors or elected federal office holders have direct ties to the groups that helped plan the January 6th rally, along with at least 15 members of Donald Trump’s former administration. The links that these Trump-allied officials have to these groups are: Turning Point Action, an arm of right-wing Turning Point USA, claimed to send “80+ buses full of patriots” to the rally that led to the Capitol riot, claiming the event would be one of the most “consequential” in U.S. history. • The group spent over $1.5 million supporting Trump and his Georgia senate allies who claimed the election was fraudulent and supported efforts to overturn it. • The organization hosted Trump at an event where he claimed Democrats were trying to “rig the election,” which he said would be “the most corrupt election in the history of our country.” • At a Turning Point USA event, Rep. -

Congress of the United States Washington, DC 20515

Congress of the United States Washington, DC 20515 June 14, 2021 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker of the House H-232, The Capitol Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Madam Speaker: We write today to urge you to fully reopen the House of Representatives. The positive impact of increasing vaccination rates and decreasing cases of COVID-19 are clear to see. Businesses are open, sporting venues and cultural institutions have welcomed back fans and visitors, and restrictions have been lifted. On June 11, Washington D.C. fully reopened and lifted the restrictions put in place to stop the spread of COVID-19. Unfortunately, the United States Capitol and the People’s House have failed to do the same. The Capitol remains closed to the American people and the House continues to maintain policies that run contrary to science of COVID-19. It is time for you to reopen the House and get back to serving the American people. Weekly case numbers in the United States have reached their lowest point since March of 2020 at the very start of the pandemic, and every day hundreds of thousands of Americans are being vaccinated. This also holds true for the Washington D.C. metropolitan area and the Capitol Hill community specifically. Over the last two weeks cases are down 36% in Washington D.C. and over 40% in both Virginia and Maryland. On Capitol Hill, no congressional staffer is known to have tested positive in weeks and no Member of Congress is known to have tested positive in months. This can no doubt be attributed to the institution’s steady access to vaccinations. -

Betomania Has Bitten the Dust, but Texas Democrats Still Have a Reason to Give a Smile Mark P

Betomania Has Bitten the Dust, But Texas Democrats Still Have a Reason to Give a Smile Mark P. Jones Baker Institute Fellow in Political Science Joseph D. Jamail Chair in Latin American Studies Rice University Shift in US House & TX Leg Seats & Appeals Judges & Harris County Comm Court Office Seats 2018 Seats 2019 Net Dem Gain US House 25 R vs. 11 D 23 R vs. 13 D +2 TX Senate 21 R vs. 10 D 19 R vs. 12 D +2 TX House 95 R vs. 55 D 83 R vs. 67 D +12 Appeals Court Judges 66 R vs. 14 D 41 R vs. 39 D +25 Harris County Comm Court 4 R vs. 1 D 3 D vs. 2 R +2 Could Have Been Worse for TX GOP • Trump + Beto + Straight Ticket Voting – Record Midterm Turnout – Greater Use of STV – Higher Democratic STV • The 5 Percenters – Statewide – US House – TX Legislature The Statewide Races: Office GOP Percent Dem Percent Margin ’18/’14 Governor Greg Abbott 56 Lupe Valdez 43 13/20 Land Comm. George P. Bush 54 Miguel Suazo 43 11/25 Comptroller Glenn Hegar 53 Joi Chevalier 43 10/20 RRC Christi Craddick 53 Roman McAllen 44 9/21* Ag. Comm Sid Miller 51 Kim Olson 46 5/22 Lt. Governor Dan Patrick 51 Mike Collier 47 4/19 Atty General Ken Paxton 51 Justin Nelson 47 4/21 US Senate Ted Cruz 51 Beto O’Rourke 48 3/27* Trump 2016: 9% Margin of Victory. Statewide GOP Judicial: 15% Margin of Victory The US House 5 Percenters & Friends District Republican Democrat 2018/2016 Margins CD‐23 Will Hurd Gina Ortiz Jones** 1/1 CD‐21 Chip Roy* Joseph Kopser 3/21* CD‐31 John Carter MJ Hegar 3/22 CD‐24 Kenny Marchant Jan McDowell 3/17 CD‐10 Michael McCaul Mike Siegel 4/19 CD‐22 Pete -

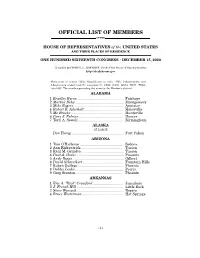

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

The Importance of Politics to CAALA and the Importance of CAALA to Politicians THIS ELECTION IS ABOUT YOUR PRACTICE

CAALA President Mike Arias ARIAS SANGUINETTI WANG & TORRIJOS, LLP October 2018 Issue The importance of politics to CAALA and the importance of CAALA to politicians THIS ELECTION IS ABOUT YOUR PRACTICE In a few short weeks, the mid-term Republicans, we will take back the House. efforts to pare down, strip down and take elections will take place, and I hope I don’t What does this mean to you as a Trial away access to justice.” Swalwell added that have to tell you how important this election Lawyer? It means that the wrath of legislta- “23 seats are between where we are and cut- is for consumer attorneys and the people tion that has emanated out of the ting in half our time in hell. We can prove we represent. Like so many CAALA mem- Republican-controlled House – that is that we are better than that in America.” bers, politics means a lot to me; not just designed to limit consumer rights, deny Katie Hill and Gil Cisneros both said they because I’m CAALA’s President and I’m trial by jury and eliminate our practices – have lived a life of service. Katie as a nurse and about to be installed as President of our will stop. Cisneros in the Navy. They say they are both state trial lawyer association, CAOC. And As is usually the case, California is at the fighting to keep President Trump from taking not because I’m a political junkie who center of the national political landscape, away what trial lawyers work to do.