An Interview with Daniel Epstein1 on Unlocking Baseball's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Topps Opening Day Baseball Checklist

BASE OD-1 Mike Trout Angels® OD-2 Noah Syndergaard New York Mets® OD-3 Carlos Santana Cleveland Indians® OD-4 Derek Norris San Diego Padres™ OD-5 Kenley Jansen Los Angeles Dodgers® OD-6 Luke Jackson Texas Rangers® Rookie OD-7 Brian Johnson Boston Red Sox® Rookie OD-8 Russell Martin Toronto Blue Jays® OD-9 Rick Porcello Boston Red Sox® OD-10 Felix Hernandez Seattle Mariners™ OD-11 Danny Salazar Cleveland Indians® OD-12 Dellin Betances New York Yankees® OD-13 Rob Refsnyder New York Yankees® Rookie OD-14 James Shields San Diego Padres™ OD-15 Brandon Crawford San Francisco Giants® OD-16 Tom Murphy Colorado Rockies™ Rookie OD-17 Kris Bryant Chicago Cubs® OD-18 Richie Shaffer Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie OD-19 Brandon Belt San Francisco Giants® OD-20 Anthony Rizzo Chicago Cubs® OD-21 Mike Moustakas Kansas City Royals® OD-22 Roberto Osuna Toronto Blue Jays® OD-23 Jimmy Nelson Milwaukee Brewers™ OD-24 Luis Severino New York Yankees® Rookie OD-25 Justin Verlander Detroit Tigers® OD-26 Ryan Braun Milwaukee Brewers™ OD-27 Chris Tillman Baltimore Orioles® OD-28 Alex Rodriguez New York Yankees® OD-29 Ichiro Miami Marlins® OD-30 R.A. Dickey Toronto Blue Jays® OD-31 Alex Gordon Kansas City Royals® OD-32 Raul Mondesi Kansas City Royals® Rookie OD-33 Josh Reddick Oakland Athletics™ OD-34 Wilson Ramos Washington Nationals® OD-35 Julio Teheran Atlanta Braves™ OD-36 Colin Rea San Diego Padres™ Rookie OD-37 Stephen Vogt Oakland Athletics™ OD-38 Jon Gray Colorado Rockies™ Rookie OD-39 DJ LeMahieu Colorado Rockies™ OD-40 Michael Taylor Washington Nationals® OD-41 Ketel Marte Seattle Mariners™ Rookie OD-42 Albert Pujols Angels® OD-43 Max Kepler Minnesota Twins® Rookie OD-44 Lorenzo Cain Kansas City Royals® OD-45 Carlos Beltran New York Yankees® OD-46 Carl Edwards Jr. -

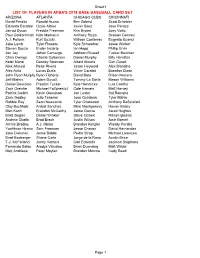

List of Players in Apba's 2018 Base Baseball Card

Sheet1 LIST OF PLAYERS IN APBA'S 2018 BASE BASEBALL CARD SET ARIZONA ATLANTA CHICAGO CUBS CINCINNATI David Peralta Ronald Acuna Ben Zobrist Scott Schebler Eduardo Escobar Ozzie Albies Javier Baez Jose Peraza Jarrod Dyson Freddie Freeman Kris Bryant Joey Votto Paul Goldschmidt Nick Markakis Anthony Rizzo Scooter Gennett A.J. Pollock Kurt Suzuki Willson Contreras Eugenio Suarez Jake Lamb Tyler Flowers Kyle Schwarber Jesse Winker Steven Souza Ender Inciarte Ian Happ Phillip Ervin Jon Jay Johan Camargo Addison Russell Tucker Barnhart Chris Owings Charlie Culberson Daniel Murphy Billy Hamilton Ketel Marte Dansby Swanson Albert Almora Curt Casali Nick Ahmed Rene Rivera Jason Heyward Alex Blandino Alex Avila Lucas Duda Victor Caratini Brandon Dixon John Ryan Murphy Ryan Flaherty David Bote Dilson Herrera Jeff Mathis Adam Duvall Tommy La Stella Mason Williams Daniel Descalso Preston Tucker Kyle Hendricks Luis Castillo Zack Greinke Michael Foltynewicz Cole Hamels Matt Harvey Patrick Corbin Kevin Gausman Jon Lester Sal Romano Zack Godley Julio Teheran Jose Quintana Tyler Mahle Robbie Ray Sean Newcomb Tyler Chatwood Anthony DeSclafani Clay Buchholz Anibal Sanchez Mike Montgomery Homer Bailey Matt Koch Brandon McCarthy Jaime Garcia Jared Hughes Brad Ziegler Daniel Winkler Steve Cishek Raisel Iglesias Andrew Chafin Brad Brach Justin Wilson Amir Garrett Archie Bradley A.J. Minter Brandon Kintzler Wandy Peralta Yoshihisa Hirano Sam Freeman Jesse Chavez David Hernandez Jake Diekman Jesse Biddle Pedro Strop Michael Lorenzen Brad Boxberger Shane Carle Jorge de la Rosa Austin Brice T.J. McFarland Jonny Venters Carl Edwards Jackson Stephens Fernando Salas Arodys Vizcaino Brian Duensing Matt Wisler Matt Andriese Peter Moylan Brandon Morrow Cody Reed Page 1 Sheet1 COLORADO LOS ANGELES MIAMI MILWAUKEE Charlie Blackmon Chris Taylor Derek Dietrich Lorenzo Cain D.J. -

Minnesota Twins Roster

MINNESOTA TWINS ROSTER MANAGER: Paul Molitor (4) COACHES: Eric Rasmussen, Pitching Coach (66); Tom Brunansky, Hitting Coach (23); Butch Davis, First Base Coach (40); Gene Glynn, Third Base Coach (13); Eddie Guardado, Bullpen Coach (18); Rudy Hernandez, Assistant Hitting Coach (63); Joe Vavra, Third Base Coach (46); Nate Dammann, Bullpen Catcher (75); Ben Richardson, Bullpen Catcher (76) HEAD ATHLETIC TRAINER: Dave Pruemer ASSISTANT ATHLETIC TRAINERS: Tony Leo, Lanning Tucker STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING COACH: Perry Castellano No. PITCHERS (13) B T HT WT Born Birthplace 58 Fernando Abad L L 6-1 220 12/17/1985 La Romana, DR TWINS NUMERICAL ROSTER 62 Buddy Boshers L L 6-3 205 05/09/1988 Huntsville, AL No. Player Pos. 64 Pat Dean L L 6-1 195 05/25/1989 Waterbury, CT 2 Dozier, Brian .................................... INF 56 Tyler Duffey R R 6-3 222 12/27/1990 Houston, TX 4 Molitor, Paul ...........................Manager 45 Phil Hughes R R 6-5 250 06/24/1986 Mission Viejo, CA 5 Escobar, Eduardo ............................ INF 7 Mauer, Joe ....................................... INF 49 Kevin Jepsen R R 6-3 235 07/26/1984 Anaheim, CA 8 Suzuki, Kurt ........................................ C 27 Brandon Kintzler R R 6-0 191 08/01/1984 Las Vegas, NV 9 Nunez, Eduardo ............................... INF 65 Trevor May R R 6-5 240 09/23/1989 Longview, WA 13 Glynn, Gene ...............Third Base Coach 47 Ricky Nolasco R R 6-2 235 12/13/1982 Corona, CA 18 Guardado, Eddie .............Bullpen Coach 57 Ryan Pressly R R 6-3 210 12/15/1988 Dallas, TX 23 Brunansky, Tom ...............Hitting Coach 24 Plouffe, Trevor ................................ -

Twins Notes, 4-16 At

MINNESOTA TWINS (6-7) AT LOS ANGELES ANGELS (7-5) FRIDAY, APRIL 16, 2021 - 6:38 P.M. (PT) - TV: BALLY SPORTS NORTH PLUS / RADIO: TIBN, WCCO, THE WOLF LHP Lewis Thorpe (2021 Debut) vs. LHP Andrew Heaney (1-1, 7.00) GAME 14 ROAD GAME 7 Upcoming Probable Pitchers & Broadcast Schedule Date Opponent Probable Pitchers Time Television Radio / Spanish Radio 4/17 at Los Angeles-AL RHP Matt Shoemaker (1-0, 4.09) vs. LHP José Quintana (0-1, 16.20) 8:07 p.m. (CT) FS1 TIBN, WCCO, The Wolf / None 4/18 at Los Angeles-AL LHP J.A. Happ (0-0, 3.12) vs. RHP Alex Cobb (1-0, 4.63) 3:07 p.m. (CT) Bally Sports North TIBN, WCCO, The Wolf / twinsbeisbol.com SEASON AT A GLANCE THE TWINS: The Twins completed their seven-game homestand with a record of 2-5, going STREAKS 1-2 vs. the Mariners and 1-3 vs. the Red Sox...tonight they will begin their second roadtrip of Under Baldelli (since '19): ...............143-92 Current Streak 1 win Home Record: ........................................2-5 the season with the first of three against the Angels in Anaheim...following this series, they Road Record: .........................................4-2 will travel north to play three against the A's in Oakland from Monday-Wednesday...the Twins Last 5 games 1-4 Record in series: ................................ 2-2-0 are 2-5 at home this season and 4-2 on the road...they were an MLB-best 24-7 at home and Last 10 games 4-6 Record in home series: ..................... -

877-446-9361 Tabletable of of Contentscontents

Hill Kelly Ad 6171 Pensacola Blvd Pensacola, FL 32505 877-446-9361 TableTABLE Of OF ContentsCONTENTS 2-4 Blue Wahoos Join Twins Territory 6 Blue Wahoos Stadium 10-11 New Foods, New Views Concessions Storefronts 13 Promotional Calendar 15 Twins Affiliates/Road To The Show 16 Manager Ramon Borrego 17 Coaching Staff 20-24 Player Bios 26 Admiral Fetterman 27 2019 Schedule 28-29 Scorecard 32-35 Pass The Mic: Broadcaster Chris Garagiola 37 Southern League Teams 39-42 Devin Smeltzer: Helping Others Beat Odds 44 How Are We Doing? 48-49 SCI: Is Your Child Ready? 53 Community Initiatives 54 Community Spotlight: Chloe Channell 59 Ballpark Rules 2019 Official Program Double-A Affiliate Minnesota Twins Blue Wahoos Join Twins Territory The Pensacola Blue Wahoos and the Minnesota Twins agreed to a two-year player development agreement for the 2019 and 2020 seasons. The new partnership will bring some of the most exciting prospects in the game to Blue Wahoos Stadium alongside the storied legacy of Twins baseball. Twins history began in 1961 when Washington Senators president Calvin Griffith made the historic decision to move his family’s team to the Midwest, settling on the Minneapolis/St. Paul area in Minnesota. The new team was named after the state’s famous Twin Cities and began their inaugual season with a talented roster featuring Harmon Killebrew, Bob Allison, Camilo Pascual, and Jim Lemon. Homegrown talents Jim Kaat, Zoilo Versalles, Jimmie Hall, and Tony Oliva combined with the Twins already potent nucleus to make the team a force to be reckoned with in the 1960s. -

Twins Notes, 10-4 at NYY – ALDS

MINNESOTA TWINS AT NEW YORK YANKEES ALDS - GAME 1, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 4, 2019 - 7:07 PM (ET) - TV: MLB NETWORK RADIO: TIBN-WCCO / ESPN RADIO / TWINSBEISBOL.COM RHP José Berríos vs. LHP James Paxton POSTSEASON GAME 1 POSTSEASON ROAD GAME 1 Upcoming Probable Pitchers & Broadcast Schedule Date Opponent Probable Pitchers Time Television Radio / Spanish Radio 10/5 at New York-AL TBA vs. RHP Masahiro Tanaka 5:07 pm (ET) Fox Sports 1 TIBN-WCCO / ESPN / twinsbeisbol.com 10/6 OFF DAY 10/7 vs. New York-AL TBA vs. RHP Luis Severino 7:40 or 6:37 pm (CT) Fox Sports 1 TIBN-WCCO / ESPN / twinsbeisbol.com SEASON AT A GLANCE THE TWINS: The Twins completed the 2019 regular season with a record of 101-61, winning the TWINS VS. YANKEES American League Central on September 25 after defeating Detroit by a score of 5-1, followed Record: ......................................... 101-61 2019 Record: .........................................2-4 Home Record: ................................. 46-35 by a White Sox 8-3 victory over the Indians later that night...the Twins will play Game 2 of this ALDS tomorrow, travel home for an off-day and a workout on Sunday (time TBA), followed Current Streak: ...............................2 losses Road Record: .................................. 55-26 2019 at Home: .......................................1-2 Record in series: .........................31-15-6 by Game 3 on Monday, which would mark the Twins first home playoff game since October Series Openers: .............................. 36-16 7, 2010 and third ever played at Target Field...the Twins spent 171 days in first place, tied 2019 at New York-AL: ............................1-2 Series Finales: ............................... -

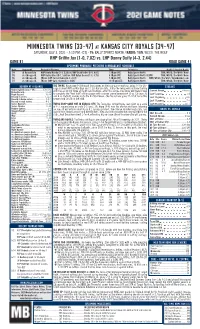

Twins Notes, 7-3 at KC

MINNESOTA TWINS (33-47) AT KANSAS CITY ROYALS (34-47) SATURDAY, JULY 3, 2021 - 3:10 P.M. (CT) - TV: BALLY SPORTS NORTH / RADIO: TIBN, WCCO, THE WOLF RHP Griffin Jax (1-0, 7.82) vs. LHP Danny Duffy (4-3, 2.44) GAME 81 ROAD GAME 41 Upcoming Probable Pitchers & Broadcast Schedule Date Opponent Probable Pitchers Time Television Radio / Spanish Radio 7/4 at Kansas City RHP Kenta Maeda (3-3, 5.56) vs. RHP Brad Keller (6-8, 6.67) 1:10 pm (CT) Bally Sports North TIBN, WCCO, The Wolf / None 7/5 vs. Chicago-AL RHP Bailey Ober (0-1, 5.84) vs. RHP Dylan Cease (7-3, 3.75) 6:10 pm (CT) Bally Sports North / ESPN TIBN, WCCO, The Wolf / None 7/6 vs. Chicago-AL TBA vs. LHP Carlos Rodón (6-3, 2.37) 7:10 pm (CT) Bally Sports North TIBN, WCCO, The Wolf / twinsbeisbol.com 7/7 vs. Chicago-AL TBA vs. RHP Lance Lynn (8-3, 2.02) 12:10 pm (CT) Bally Sports North TIBN, WCCO, The Wolf / None SEASON AT A GLANCE THE TWINS: Have gone 0-4 through four games on their six-game roadtrip, going 0-3 in Chi- STREAKS cago (rainout/PPD on Monday) and 0-1 in Kansas City...today the Twins will continue the trip Under Baldelli (since '19): .............170-132 Current Streak 4 losses Home Record: ....................................17-23 with the second of three at Kauffman Stadium...after this series, the Twins will travel home Road Record: .....................................16-24 to complete the "first half" of the season with a seven-game homestand (3 vs. -

Minnesota Twins Roster

MINNESOTA TWINS ROSTER MANAGER: Rocco Baldelli (5) COACHES: Mike Bell, Bench Coach (27); Tony Diaz, Third Base/IF Coach (46); Rudy Hernandez, Hitting Coach (63); Wes Johnson, Pitching Coach (47); Pete Maki, Bullpen Coach (88); Edgar Varela, Hitting Coach (84); Tommy Watkins, First Base/OF Coach (40); Nate Dammann, QC Coach (75); Garrett Kennedy, Bullpen Catcher (97); Connor Olson, Bullpen Catcher (98) HEAD ATHLETIC TRAINER: Michael Salazar ASST. ATHLETIC TRAINERS: Masa Abe, Matt Biancuzzo STRENGTH & CONDITIONING: Ian Kadish, Andrea Hayden PHYSICAL THERAPIST: Jeff Lahti MASSAGE THERAPIST: Kelli Bergheim No. PITCHERS (13) B T HT WT Born Birthplace TWINS NUMERICAL ROSTER 17 José Berríos R R 6-0 205 05/27/1994 Bayamón, PR No. Player Pos. 36 Tyler Clippard R R 6-3 200 02/14/1985 Lexington, KY 2 Arraez, Luis ............................................IF 68 Randy Dobnak R R 6-1 230 01/17/1995 South Park, PA 5 Baldelli, Rocco ............................Manager 8 Garver, Mitch ..........................................C 21 Tyler Duffey R R 6-3 220 12/27/1990 Houston, TX 9 Gonzalez, Marwin ............................. IF/OF 18 Kenta Maeda R R 6-1 185 04/11/1988 Osaka, Japan 11 Polanco, Jorge ........................................IF 65 Trevor May R R 6-5 240 09/23/1989 Longview, WA 12 Odorizzi, Jake ......................................RHP 12 Jake Odorizzi R R 6-2 190 03/27/1990 Breese, IL 13 Adrianza, Ehire .......................................IF 35 Michael Pineda R R 6-7 280 01/18/1989 Yaguate, DR 16 Avila, Alex ...............................................C 17 Berríos, José .......................................RHP 55 Taylor Rogers L L 6-3 190 12/17/1990 Denver, CO 18 Maeda, Kenta .....................................RHP 54 Sergio Romo R R 5-11 185 03/04/1983 Brawley, CA 20 Rosario, Eddie ..................................... -

2021 Topps Museum Collection Checklist.Xls

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Casey Mize Detroit Tigers® Rookie 2 Christian Yelich Milwaukee Brewers™ 3 Juan Soto Washington Nationals® 4 Alex Bregman Houston Astros® 5 Nolan Arenado St. Louis Cardinals® 6 Barry Larkin Cincinnati Reds® 7 Ketel Marte Arizona Diamondbacks® 8 Fernando Tatis Jr. San Diego Padres™ 9 Ron Santo Chicago Cubs® 10 Gerrit Cole New York Yankees® 11 Frank Robinson Baltimore Orioles® 12 Harmon Killebrew Minnesota Twins® 13 George Brett Kansas City Royals® 14 Cristian Pache Atlanta Braves™ Rookie 15 David Ortiz Boston Red Sox® 16 Robin Yount Milwaukee Brewers™ 17 Sammy Sosa Chicago Cubs® 18 Matt Chapman Oakland Athletics™ 19 Vladimir Guerrero Jr. Toronto Blue Jays® 20 Nate Pearson Toronto Blue Jays® Rookie 21 Babe Ruth New York Yankees® 22 Jorge Soler Kansas City Royals® 23 Ernie Banks Chicago Cubs® 24 Blake Snell San Diego Padres™ 25 Jacob deGrom New York Mets® 26 Sam Huff Texas Rangers® Rookie 27 Cal Ripken Jr. Baltimore Orioles® 28 Mike Schmidt Philadelphia Phillies® 29 Bryce Harper Philadelphia Phillies® 30 Carlos Correa Houston Astros® 31 Xander Bogaerts Boston Red Sox® 32 Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® 33 Joe Mauer Minnesota Twins® 34 Ichiro Seattle Mariners™ 35 Javier Baez Chicago Cubs® 36 Jose Ramirez Cleveland Indians® 37 Nick Madrigal Chicago White Sox® Rookie 38 Clayton Kershaw Los Angeles Dodgers® 39 Ted Williams Boston Red Sox® 40 Mookie Betts Los Angeles Dodgers® 41 Ryan Mountcastle Baltimore Orioles® Rookie 42 Cody Bellinger Los Angeles Dodgers® 43 Rickey Henderson Oakland Athletics™ 44 Eloy Jimenez Chicago White Sox® 45 Pete Alonso New York Mets® 46 Vladimir Guerrero Montréal Expos™ 47 Bob Gibson St. -

Play Ball in Style

Manager: Scott Servais (9) NUMERICAL ROSTER 1 Kyle Lewis OF 2 Tom Murphy C 3 J.P. Crawford INF 4 Shed Long Jr. INF 6 Perry Hill COACH 7 Marco Gonzales LHP 8 Jack Mayfield INF 9 Scott Servais MANAGER 12 Evan White INF 14 Manny Acta COACH 15 Kyle Seager INF 16 Drew Steckenrider RHP 17 Mitch Haniger OF 18 Yusei Kikuchi LHP 20 Taylor Trammell OF 21 Tim Laker COACH 23 Ty France INF 25 Dylan Moore INF 27 Dillon Thomas OF 28 Jake Fraley OF 31 Donovan Walton INF 32 Pete Woodworth COACH 33 Justus Sheffield LHP 35 Justin Dunn RHP 36 Logan Gilbert RHP 37 Paul Sewald RHP 38 Anthony Misiewicz LHP 39 Carson Vitale COACH 45 Yacksel Ríos RHP 47 Rafael Montero RHP 48 Jared Sandberg COACH 49 Kendall Graveman RHP 50 Erik Swanson RHP 53 Will Vest RHP 57 Héctor Santiago LHP 66 Fleming Baez COACH 77 Chris Flexen RHP 78 José Godoy C 79 Trent Blank COACH 84 JT Chargois RHP 88 Jarret DeHart COACH 89 Nasusel Cabrera COACH 99 Keynan Middleton RHP SEATTLE MARINERS ROSTER NO. PITCHERS (14) B-T HT. WT. BORN BIRTHPLACE 84 JT Chargois S-R 6-3 200 12/03/90 Sulphur, LA 35 Justin Dunn (IL) R-R 6-2 185 09/22/95 Freeport, NY 77 Chris Flexen R-R 6-3 230 07/01/94 Newark, CA 36 Logan Gilbert R-R 6-6 225 05/05/97 Apopka, FL PLAY BALL IN STYLE. 7 Marco Gonzales L-L 6-1 199 02/16/92 Fort Collins, CO 49 Kendall Graveman (IL) R-R 6-2 200 12/21/90 Alexander City, AL MARINERS SUITES PROVIDE THE PERFECT 18 Yusei Kikuchi L-L 6-0 200 06/17/91 Morioka, Japan SETTING FOR YOUR NEXT EVENT. -

Minnesota Twins Roster

MINNESOTA TWINS ROSTER MANAGER: Rocco Baldelli (5) COACHES: Tony Diaz, Third Base/IF Coach (46); Bill Evers, Major League Coach (67); Rudy Hernandez, Hitting Coach (63); Wes Johnson, Pitching Coach (47); Pete Maki, Bullpen Coach (88); Kevin Morgan, ML Field Coord. (12); Edgar Varela, Hitting Coach (84); Tommy Watkins, First Base/OF Coach (40); Nate Dammann, QC Coach (75); Garrett Kennedy, Bullpen Catcher (97); Connor Olson, Bullpen Catcher (98) HEAD ATHLETIC TRAINER: Michael Salazar ASST. ATHLETIC TRAINERS: Masa Abe, Matt Biancuzzo STRENGTH & CONDITIONING: Ian Kadish, Andrea Hayden PHYSICAL THERAPIST: Adam Diamond MASSAGE THERAPIST: Kelli Bergheim No. PITCHERS (13) B T HT WT Born Birthplace 66 Jorge Alcala R R 6-3 205 07/28/1995 Bajos De Haina, DR TWINS NUMERICAL ROSTER 41 Shaun Anderson R R 6-4 228 10/29/1994 Coral Springs, FL No. Player Pos. 2 Arraez, Luis ...................................... IF/OF 17 José Berríos R R 6-0 205 05/27/1994 Bayamón, PR 5 Baldelli, Rocco ............................Manager 48 Alex Colomé R R 6-1 225 12/31/1988 Santo Domingo, DR 8 Garver, Mitch ..........................................C 21 Tyler Duffey R R 6-3 220 12/27/1990 Houston, TX 9 Simmons, Andrelton ............................. SS 33 J.A. Happ L L 6-5 205 10/19/1982 Peru, IL 11 Polanco, Jorge ........................................IF 54 Derek Law R R 6-3 225 09/14/1990 Pittsburgh, PA 12 Morgan, Kevin .................. ML Field Coord. 18 Kenta Maeda R R 6-1 185 04/11/1988 Osaka, Japan 17 Berríos, José .......................................RHP -

The BG News May 02, 2019

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 5-2-2019 The BG News May 02, 2019 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation State University, Bowling Green, "The BG News May 02, 2019" (2019). BG News (Student Newspaper). 9101. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/9101 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. bg HEAVEN SPEAKS news An independent student press serving the campus and surrounding community, ESTABLISHED 1920 Bowling Green State University Thursday, May 2, 2019 Volume 98, Issue 54 University class to teach DIY reusable bags PAGE 5 ‘Me Too’ movement founder Study shows plant Tarana Burke says her ownership helps inspiration comes from a mental health woman she calls ‘Heaven’ PAGE 6 PAGE 8 PHOTO BY MICHAELA DAVIS Visit us on our Website for our MECCA 2019-2020 FULL LISTING! MANAGEMENT, INC. RESIDENTIAL • COMMERCIAL • INDUSTRIAL meccabg.com 1045 N. Main St. Bowling Green, OH 43402 . 419.353.5800 BE SMART. STUDENT LEGAL SERVICES BE SAFE. BE COVERED. REAL LAWYERS | REAL RESULTS just $9/semester [email protected] | 419-372-2951 www.bgsu.edu/sls SLS_Blotter_4x2.indd 4 8/22/18 12:47 PM BG NEWS May 2, 2019 | PAGE 2 Student runs for 1st Ward City Council Brian Geyer “I never used to be interested in politics – said that by running on the city ticket she’ll Stump VIA FACEBOOK Falcon Communications which is really interesting.