A Study of Informal Adjudication Procedures* Paul R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 134/Friday, July 16, 2021/Rules

37674 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 134 / Friday, July 16, 2021 / Rules and Regulations (Federalism), it is determined that this DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, action does not have sufficient DC 20530. Comments received by mail federalism implications to warrant the 28 CFR Part 50 will be considered timely if they are preparation of a Federalism Assessment. [Docket No. OAG 174; AG Order No. 5077– postmarked on or before August 16, As noted above, this action is an 2021] 2021. The electronic Federal eRulemaking portal will accept order, not a rule. Accordingly, the RIN 1105–AB61 comments until Midnight Eastern Time Congressional Review Act (CRA) 3 is at the end of that day. inapplicable, as it applies only to rules. Processes and Procedures for FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: 5 U.S.C. 801, 804(3). It is in the public Issuance and Use of Guidance Robert Hinchman, Senior Counsel, interest to maintain the temporary Documents Office of Legal Policy, U.S. Department placement of N-ethylhexedrone, a-PHP, AGENCY: Office of the Attorney General, of Justice, telephone (202) 514–8059 4-MEAP, MPHP, PV8, and 4-chloro-a- Department of Justice. (not a toll-free number). PVP in schedule I because they pose a ACTION: Interim final rule; request for SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: public health risk, for the reasons comments. expressed in the temporary scheduling I. Posting of Public Comments order (84 FR 34291, July 18, 2019). The SUMMARY: This interim final rule Please note that all comments temporary scheduling action was taken (‘‘rule’’) implements Executive Order received are considered part of the pursuant to 21 U.S.C. -

U.S. Core+ for Firms, Government Institutions, and Other Organizations

U.S. CORE+ FOR FIRMS, GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS, AND OTHER ORGANIZATIONS Choose HeinOnline and give your organization the competitive advantage with our premier online legal research package offering 30 databases of current and historical content. THE HEINONLINE ADVANTAGE FEATURED DATABASES IN THE PACKAGE Affordable • Brennan Center for Justice Publications • Canada Supreme Court Reports In addition to the wealth of material • Civil Rights and Social Justice - New at an incredible price, more than one • Code of Federal Regulations million pages are added to HeinOnline each month. The value of a subscription • COVID-19: Pandemics Past and Present - New increases with each content release. • Criminal Justice & Criminology • Early American Case Law • English Reports Comprehensive • European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) HeinOnline contains more than 3,000 • Executive Privilege - New journals on a variety of subjects. All • Fastcase (U.S. State & Federal Case Law) journals date back to inception, and • Federal Register Library more than 90% are available through the • GAO Reports and Comptroller General Decisions current issue or volume. • Gun Regulation and Legislation in America • Law Journal Library Authoritative • Legal Classics • Military and Government - New HeinOnline is composed of image-based • Open Society Justice Initiative - New PDFs, which are as authoritative as print • Pentagon Papers material for citation purposes, because • Revised Statutes of Canada they are exact facsimiles of the original print materials. • Statutes of the Realm • U.S. Code • U.S. Congressional Documents Incredible Customer Service • U.S. Congressional Serial Set HeinOnline’s support team is second to • U.S. Federal Legislative History Library none, providing users with searching • U.S. Presidential Impeachment Library - New and document retrieval assistance, • U.S. -

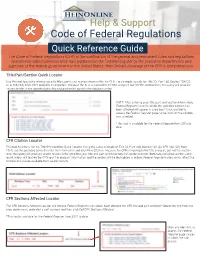

Code of Federal Regulations | Quick Reference Guide

Help & Support Help & Support Code of Federal Regulations Quick Reference Guide The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) is the codification of the general and permanent rules and regulations (sometimes called administrative law) published in the Federal Register by the executive departments and agencies of the federal government of the United States. HeinOnline’s coverage of the CFR is comprehensive. Title/Part/Section Quick Locator Use this tool to quickly retrieve specific titles, parts, and sections from within the CFR. For example, search for Title 33, Part 160, Section 204 (33 CFR 160.204) from 2015 and click Find Section. Because the CFR is indexed to the title and part, but not the section level, this query will produce search results in the specified year, title and part which contain the section number. NOTE: After entering year, title, part, and section information, Federal Register issues in which the specified citation has been affected will appear in a red box.* Click any link to access the Federal Register page range in which the citation was affected. *This tool is available for the Federal Register from 2015 to date. CFR Citation Locator This tool functions like the Title/Part/Section Quick Locator. Using the same example of Title 33, Part 160, Section 204 (33 CFR 160.204) from 2015, use the provided boxes to enter the information and click Find Citation. Because the CFR is indexed to the title and part, but not the section level, this query will produce search results in the specified year, title and part which contain the section number. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 248/Friday, December 27, 2019

71714 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 248 / Friday, December 27, 2019 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION procedures for the review and clearance Department’s rulemaking process can be of guidance documents; and (3) a found at 49 CFR 5.5. Office of the Secretary General Counsel memorandum, This final rule reflects the existing ‘‘Procedural Requirements for DOT role of the Department’s Regulatory 14 CFR Parts 11, 300, and 302 Enforcement Actions’’ (February 15, Reform Task Force in the development 2019),3 which clarifies the procedural of the Department’s regulatory portfolio 49 CFR Parts 1, 5, 7, 106, 211, 389, 553, requirements governing enforcement and ongoing review of regulations. and 601 actions initiated by the Department, Established in response to Executive including administrative enforcement Order 13777, ‘‘Enforcing the Regulatory RIN 2105–AE84 proceedings and judicial enforcement Reform Agenda’’ (February 24, 2017), Administrative Rulemaking, Guidance, actions brought in Federal court. the Regulatory Reform Task Force is the and Enforcement Procedures This final rule removes the existing Department’s internal body, chaired by procedures on rulemaking, which are the Regulatory Reform Officer, tasked AGENCY: Office of the Secretary of outdated and inconsistent with current with evaluating proposed and existing Transportation (OST), U.S. Department departmental practice, and replaces regulations and making of Transportation (DOT). them with a comprehensive set of recommendations to the Secretary of ACTION: Final rule. procedures that will increase Transportation regarding their transparency, provide for more robust promulgation, repeal, replacement, or SUMMARY: This final rule sets forth a public participation, and strengthen the modification, consistent with applicable comprehensive revision and update of overall quality and fairness of the law. -

Attorney General's Manual on The

Attorney GeneraI's'Man~al on the Administrative Procedure Act WM. W. GAUNT 6' SONS, INC. Holmes Beach, Florida 33510 1973 ~ ;' Wm. W. Gaunt & Sons, Inc Reprint Edition This is an unabridged republication of the first editign published in [~H7 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 7Z-97700 International Standard Book Number 9 12004 - 11 - 4 Published by Wm. W. Gaunt & Sons, Inc. 3011 Gulf Drive, Holmes Beach, Florida 33510 Printed in the United States of America by Jones Offset, Inc., Bradenton Beach, Florida 33510 Attorney General's Manual on the Administrative Procedure Act Prepared by the United States Department of Justice TOM C. CLARK Attorney General TAnLB OF CONTENTS Pa~ INTRODUCTION . 5 Note Concerning Manner of Citation of Legi.dative MateriaL . 8 I-FuNDAMJo:NTAL CONC'EPTIl . 9 •.\. •• ~a..lic PurpO!le:lof the, ~dmin.htra~ive Procedure Act . 9 b. Coverage of the Admlm:ltrallve I roeedure Act.. : . 9 :=) c. Distinction between Hille Making an<1 Adjudieation .. 12 ,/ . II-SeCTION 3, PUBLIC INfORMATION. .. 17 .. Agencies Subject to Section 3 . 17 Exceptions to Requirement! of Section 3........... .. 17 (1) Any function of the United State3 rerluiring secrecy in the public interest . 17 (2) Any matter relatinlf !lo]rdy to the internal management of an agency.. 18 Effective Date-Pro3pectlve Operation............. .. 18 SECTION 3 (a)-RULES...................................... 19 Separate Statement._.................... 19 Description of Organization......... 19 Statement of Procedures. .. 20 Substantive Rules.................... .. .. 22 Section 3 (b)-Opinions and Or'!eri............ 23 24 1I~~~T:o~C)~Kt~~C fi~~~[~~.::: .• :::::.::.. :.. :::::::::::::·::::::::::::.:::::::::::::::::::~::: 26 Exceptions (1) Any military, naval, or foreign alTairs function of the United StatelJ... -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 124/Friday, June 26

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 124 / Friday, June 26, 2020 / Rules and Regulations 38301 the applicant’s or co-applicant’s day delayed effective date for SMALL BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION ethnicity, race, sex, and age as ‘‘not substantive rules under section 553(d) applicable’’ if the applicant or co- of the Administrative Procedure Act.7 13 CFR Part 120 applicant is not a natural person. For Therefore, this rule is effective on June [Docket No. SBA–2020–0039] these reasons, the Bureau will not count 26, 2020, the same date that it is first-lien originations reported in HMDA published in the Federal Register. RIN 3245–AH53 data for which both the applicant’s and III. Regulatory Requirements co-applicant’s ethnicity, race, sex, and Business Loan Program Temporary age all are reported as follows: (1) The This rule articulates the Bureau’s Changes; Paycheck Protection applicant’s ethnicity is reported as ‘‘Not interpretation of Regulation Z and TILA. Program—Additional Eligibility applicable’’ (HMDA Code 4); (2) the Revisions to First Interim Final Rule applicant’s race is reported as ‘‘Not As an interpretive rule, it is exempt applicable’’ (HMDA Code 7); (3) the from the notice-and-comment AGENCY: U.S. Small Business applicant’s sex is reported as ‘‘Not rulemaking requirements of the Administration. 8 applicable’’ (HMDA Code 4); (4) the Administrative Procedure Act. Because ACTION: Interim final rule. applicant’s age is reported as ‘‘Not no notice of proposed rulemaking is applicable’’ (HMDA Code 8888); (5) the required, the Regulatory Flexibility Act SUMMARY: On April 2, 2020, the U.S. -

Counting Regulations: an Overview of Rulemaking, Types of Federal Regulations, and Pages in the Federal Register

Counting Regulations: An Overview of Rulemaking, Types of Federal Regulations, and Pages in the Federal Register Updated September 3, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R43056 Counting Regulations Summary Federal rulemaking is an important mechanism through which the federal government implements policy. Federal agencies issue regulations pursuant to statutory authority granted by Congress. Therefore, Congress may have an interest in performing oversight of those regulations, and measuring federal regulatory activity can be one way for Congress to conduct that oversight. The number of federal rules issued annually and the total number of pages in the Federal Register are often referred to as measures of the total federal regulatory burden. Certain methods of quantifying regulatory activity, however, may provide an imperfect portrayal of the total federal rulemaking burden. For example, the number of final rules published each year is generally in the range of 3,000-4,500, according to the Office of the Federal Register. Some of those rules have a large effect on the economy, and others have a significant legal and/or policy effect, even if the direct economic effects of the regulation are minimal. On the other hand, many federal rules are routine in nature and impose minimal regulatory burden, if any. In addition, rules that are deregulatory in nature and those that repeal existing rules are still defined as “rules” under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA, 5 U.S.C. §§551 et seq.) and are therefore generally included in counts of total regulatory activity, even though they do not impose a new net regulatory burden. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 135/Tuesday, July 14, 2020/Rules

42494 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 135 / Tuesday, July 14, 2020 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE docket number or RIN for this FIRREA Financial Institutions Reform, rulemaking. All comments received will Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989 Rural Utilities Service be posted without change to https:// FR Federal Register www.regulations.gov, including any FSRIA Farm Security and Rural Investment Rural Housing Service Act of 2002 personal information provided. GAAP Generally accepted accounting Docket: For access to the docket to principles Rural Business-Cooperative Service read background documents or GPO Government Printing Office comments received, go to https:// ICBA Independent Community Bankers of 7 CFR Parts 1779, 3575, 4279, 4287, www.regulations.gov. America and 5001 LNG Loan Note Guarantee FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: NEPA National Environmental Policy Act [Docket No. RUS–19-Agency–0030] Thomas P. Dickson, Regulations NMTC New Markets Tax Credit Management Division Team 2, Rural RIN 0572–AC43 OGC Office of General Counsel Development Innovation Center, U.S. OMB Office of Management and Budget OneRD Guaranteed Loan Regulation Department of Agriculture, 1400 OneRD OneRD Guaranteed Loan Program Independence Ave. SW, Stop 1522, PER Preliminary Engineering Reports AGENCY: Rural Business-Cooperative Washington, DC 20250; telephone 202– QALICB Qualified Active Low Income Service, Rural Housing Service, Rural 690–4492; email thomas.dickson@ Community Business Utilities Service, USDA. RD Rural Development usda.gov. REAP Rural Energy for America Program ACTION: Final rule; request for SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: RFA Regulatory Flexibility Act comments. RMA Risk Management Association Table of Contents for Preamble SAM System for Award Management SUMMARY: The Rural Business- § Section Cooperative Service, Rural Housing I. -

Reg Flex Agenda

16848 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 60 / Wednesday, March 31, 2021 / UA: Reg Flex Agenda REGULATORY INFORMATION selected for periodic review under Office of Management and Budget SERVICE CENTER section 610 of the Regulatory Flexibility Office of National Drug Control Policy Act. Office of Personnel Management Introduction to the Unified Agenda of The complete fall 2020 Unified Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation Federal Regulatory and Deregulatory Agenda contains the Regulatory Plans of Small Business Administration Social Security Administration Actions—Fall 2020 28 Federal agencies and 68 Federal agency regulatory agendas. Independent Regulatory Agencies AGENCY: Regulatory Information Service ADDRESSES: Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Center. Regulatory Information Service Center (MVE), General Services Consumer Product Safety Commission ACTION: Introduction to the Regulatory Administration, 1800 F Street NW, Federal Trade Commission Plan and the Unified Agenda of Federal 2219F, Washington, DC 20405. National Indian Gaming Commission Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions. Nuclear Regulatory Commission FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: For Federal Permitting Improvement Steering SUMMARY: Publication of the Unified further information about specific Council regulatory actions, please refer to the Agenda of Regulatory and Deregulatory Agency Agendas Actions and the Regulatory Plan agency contact listed for each entry. To represent key components of the provide comment on or to obtain further Cabinet Departments regulatory planning -

ADS Chapter 516

ADS Chapter 516 Federal Register Notices Partial Revision Date: 04/19/2019 Responsible Office: M/MS/IRD Filename: 516_041919 04/19/2019 Partial Revision Functional Series 500 – Management Services ADS 516 – Federal Register Notices POC for ADS 516: Coy Lindsay, (202) 921-5017, [email protected] Table of Contents 516.1 OVERVIEW .................................................................................................... 3 516.2 PRIMARY RESPONSIBILITIES .................................................................... 4 516.3 POLICY DIRECTIVES AND REQUIRED PROCEDURES ............................. 4 516.3.1 Writing and Clearing Federal Register Documents ................................... 4 516.3.2 Preparation and Processing of Federal Register Package ....................... 5 516.3.3 Public Inspection of Documents ................................................................. 5 516.3.3.1 Correcting or Withdrawing a Federal Register Submission ............................ 6 516.3.3.2 Emergency Publications ................................................................................. 6 516.4 MANDATORY REFERENCES ...................................................................... 6 516.4.1 External References ..................................................................................... 6 516.4.2 Internal Mandatory References ................................................................... 7 516.5 ADDITIONAL HELP....................................................................................... 7 516.6 -

Regulatory Flexibility Act

Regulatory Flexibility Act The following text of the Regulatory Flexibility Act of 1980, as amended, is taken from Title 5 of the United States Code, sections 601 – 612 (The Regulatory Flexibility Act was originally passed in 1980 (P. L. 96-354). The Act was amended by the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-121).) Congressional Findings and Declaration of Purpose (a) The Congress finds and declares that —(1) when adopting regulations to protect the health, safety and economic welfare of the Nation, Federal agencies should seek to achieve statutory goals as effectively and efficiently as possible without imposing unnecessary burdens on the public; (2) laws and regulations designed for application to large scale entities have been applied uniformly to small businesses, small organizations, and small governmental jurisdictions even though the problems that gave rise to government action may not have been caused by those smaller entities; (3) uniform Federal regulatory and reporting requirements have in numerous instances imposed unnecessary and disproportionately burdensome demands including legal, accounting and consulting costs upon small businesses, small organizations, and small governmental jurisdictions with limited resources; (4) the failure to recognize differences in the scale and resources of regulated entities has in numerous instances adversely affected competition in the marketplace, discouraged innovation and restricted improvements in productivity; (5) unnecessary regulations create entry barriers -

Department of Health and Human Services

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 07/15/2013 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2013-16271, and on FDsys.gov DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 42 CFR Parts 431, 435, 436, 438, 440, 447, and 457 Office of the Secretary 45 CFR Parts 155 and 156 [CMS-2334-F] RIN 0938-AR04 Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Programs: Essential Health Benefits in Alternative Benefit Plans, Eligibility Notices, Fair Hearing and Appeal Processes, and Premiums and Cost Sharing; Exchanges: Eligibility and Enrollment AGENCY: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: This final rule implements provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (collectively referred to as the Affordable Care Act. This final rule finalizes new Medicaid eligibility provisions; finalizes changes related to electronic Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) eligibility notices and delegation of appeals; modernizes and streamlines existing Medicaid eligibility rules; revises CHIP rules relating to the substitution of coverage to improve the coordination of CHIP coverage with other coverage; and amends requirements for benchmark and benchmark-equivalent benefit packages consistent with sections 1937 of the Social Security Act (which we refer to as “alternative benefit plans”) to ensure that these benefit packages include essential health benefits and meet certain other minimum standards. This rule also implements specific provisions including those related to authorized representatives, notices, and verification of eligibility for qualifying coverage in an eligible employer-sponsored CMS-2334-F 2 plan for Affordable Insurance Exchanges.