PROGRAM NOTES by Geoffrey D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aaron Copland

9790051721474 Orchestra (score & parts) Aaron Copland John Henry 1940,rev.1952 4 min for orchestra 2(II=picc ad lib).2(1).2.2(1)-2.2.1.0-timp.perc:anvil/tgl/BD/SD/sand paper-pft(ad lib)-strings 9790051870714 (Parts) Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Aaron Copland photo © Roman Freulich Midday Thoughts Aaron Copland, arranged by David Del Tredici 2000 3 min CHAMBER ORCHESTRA for chamber ensemble Appalachian Spring 1(=picc.).2.2.bcl.2-2.0.0.0-strings Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Suite for 13 instruments 1970 25 min Music for Movies Chamber Suite 1942 16 min 1.0.1.1-0.0.0.0-pft-strings(2.2.2.2.1) for orchestra <b>NOTE:</b> An additional insert of section 7, "The Minister's Dance," is available for 1(=picc).1.1.1-1.2.1.0-timp.perc(1):glsp/xyl/susp.cym/tgl/BD/SD- performance. This version is called "Complete Ballet Suite for 13 Instruments." pft(harp)-strings 9790051096442 (Full score) 9790051094073 (Full score) Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world 9790051214297 Study Score - Hawkes Pocket Score 1429 9790051208760 Study Score - Hawkes Pocket Score 876 Music for the Theatre 9790051094066 (Full score) 1925 22 min Billy the Kid for chamber orchestra Waltz 1(=picc).1(=corA).1(=Eb).1-0.2.1.0-perc:glsp/xyl/cyms/wdbl/BD/SD- pft-strings 1938 4 min 9790051206995 Study Score - Hawkes Pocket Score 699 for chamber orchestra Availability: This work is available from Boosey -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 44,1924-1925, Trip

SANDERS THEATRE . CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY Thursday Evening, November 6, at 8.00 ,jgr BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA mc. FORTY-FOURTH SEASON <* I924^J925 ^ PRoGRZWIE 21 iTIfli'MIVIfl STEINWAY STEINERT JEWETT WOODBURY PIANOS DUOART Reproducing Pianos Pianola Pianos *% VICTROLAS VICTOR RECORDS DeForest Radio Merchandise ML STEINERT & SONS 162 Boylston Street 35 Arch Street BOSTON, MASS. SANDERS THEATRE . CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY FORTY-FOURTH SEASON, 1924-1925 INC. SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor SEASON 1924-1925 THURSDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 6, at 8.00 o'clock WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1924, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. FREDERICK P. CABOT President GALEN L. STONE . " . Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE Treasurer FREDERICK P. CABOT HENRY B. SAWYER ERNEST B. DANE GALEN L. STONE M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE BENTLEY W. WARREN JOHN ELLERTON LODGE E. SOHIER WELCH ARTHUR LYMAN W. H. BRENNAN, Manager G. E. JUDD, Assistant Manager 1 — 1 E. i TH£ INSTRUMENT OF THE IMMORTALS IT IS true that Rachmaninov, Pader- Each embodies all the Steinway ewski, Hofmann—to name but a few principles and ideals. And each waits of a long list of eminent pianists only your touch upon the ivory keys have chosen the Steinway as the one to loose its matchless singing tone, perfect instrument. It is true that in to answer in glorious voice your the homes of literally thousands of quickening commands, to echo in singers, directors and musical celebri- lingering beauty or rushing splendor ties, the Steinway is an integral part the genius of the great composers. -

Symphony Shopping

Table of Contents | Week 1 7 bso news 15 on display in symphony hall 16 bso music director andris nelsons 18 the boston symphony orchestra 21 a message from andris nelsons 22 this week’s program Notes on the Program 24 The Program in Brief… 25 Dmitri Shostakovich 33 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky 41 Sergei Rachmaninoff 49 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artist 55 Evgeny Kissin 58 sponsors and donors 78 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 83 symphony hall information the friday preview talk on october 2 is given by bso director of program publications marc mandel. program copyright ©2015 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. program book design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photo of Andris Nelsons by Chris Lee cover design by BSO Marketing BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617)266-1492 bso.org andris nelsons, ray and maria stata music director bernard haitink, lacroix family fund conductor emeritus seiji ozawa, music director laureate 135th season, 2015–2016 trustees of the boston symphony orchestra, inc. William F. Achtmeyer, Chair • Paul Buttenwieser, President • George D. Behrakis, Vice-Chair • Cynthia Curme, Vice-Chair • Carmine A. Martignetti, Vice-Chair • Theresa M. Stone, Treasurer David Altshuler • Ronald G. Casty • Susan Bredhoff Cohen • Richard F. Connolly, Jr. • Alan J. Dworsky • Philip J. Edmundson, ex-officio • William R. Elfers • Thomas E. Faust, Jr. • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Susan Hockfield • Barbara W. Hostetter • Stephen B. Kay • Edmund Kelly • Martin Levine, ex-officio • Joyce Linde • John M. Loder • Nancy K. Lubin • Joshua A. Lutzker • Robert J. Mayer, M.D. -

Production Database Updated As of 25Nov2020

American Composers Orchestra Works Performed Workshopped from 1977-2020 firstname middlename lastname Date eventype venue work title suffix premiere commission year written Michael Abene 4/25/04 Concert LGCH Improv ACO 2004 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Piano Improv Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Violin & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Double Bass & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/9/00 Concert CH Tomorrow's Song, as Yesterday Sings Today World 2000 Ricardo Lorenz Abreu 12/4/94 Concert CH Concierto para orquesta U.S. 1900 John Adams 4/25/83 Concert TULLY Shaker Loops World 1978 John Adams 1/11/87 Concert CH Chairman Dances, The New York ACO-Goelet 1985 John Adams 1/28/90 Concert CH Short Ride in a Fast Machine Albany Symphony 1986 John Adams 12/5/93 Concert CH El Dorado New York Fromm 1991 John Adams 5/17/94 Concert CH Tromba Lontana strings; 3 perc; hp; 2hn; 2tbn; saxophone1900 quartet John Adams 10/8/03 Concert CH Christian Zeal and Activity ACO 1973 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH The Wound-Dresser 1988 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH My Father Knew Charles Ives ACO 2003 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH Violin Concerto 1993 John Luther Adams 10/15/10 Concert ZANKL The Light Within World 2010 Victor Adan 10/16/11 Concert MILLR Tractus World 0 Judah Adashi 10/23/15 Concert ZANKL Sestina World 2015 Julia Adolphe 6/3/14 Reading FISHE Dark Sand, Sifting Light 2014 Kati Agocs 2/20/09 Concert ZANKL Pearls World 2008 Kati Agocs 2/22/09 Concert IHOUS -

Aaron Copland: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

AARON COPLAND: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1922-25/32: Ballet “Grogh”: 30 minutes 1922-25: Dance Symphony: 18 minutes 1923: “Cortege macabre” for orchestra: 8 minutes 1923-28: Two Pieces for String Orchestra: 10 minutes 1924: Symphony for Organ and orchestra: 24 minutes 1925: Suite “Music for the Theater” for small orchestra: 21 minutes 1926: Piano Concerto: 16 minutes 1927-29/55: Symphonic Ode for orchestra: 19 minutes 1928: Symphony No.1 (revised version of Symphony for Organ) 1930/57: Orchestral Variations: 12 minutes 1931-33: Short Symphony (Symphony No.2): 15 minutes 1934/35: Ballet “Hear Ye! Hear Ye!”: 32 minutes 1934-35: “Statements” for orchestra: 18 minutes 1936: “El salon Mexico” for orchestra: 10 minutes 1937: “Prairie Journal” (“Music for Radio”) for orchestra: 11 minutes 1938: Ballet “Billy the Kid”: 32 minutes (and Ballet Suite: 22 minutes) (and extracted Waltz and Celebration for concert band: 6 minutes) 1940/41: “An Outdoor Overture” for orchestra or concert band: 10 minutes 1940: Suite “A Quiet City” for trumpet, cor anglais and strings: 10 minutes 1940/52: “John Henry” for orchestra: 4 minutes 1942: “A Lincoln Portrait” for narrator and orchestra or concert band: 15 minutes Ballet “Rodeo”: 23 minutes (and Four Dance Episodes: 19 minutes) “Fanfare for the Common Man” for brass and percussion: 2 minutes “Music for the Movies” for orchestra: 17 minutes 1942/44: “Danzon Cubano” for orchestra: 6 minutes 1943: “Song of the Guerillas” for orchestra 1944: Ballet “Appalachian Spring” for orchestra or chamber orchestra: -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 120, 2000-2001, Subscription, Volume 02

BOSTON SYMPHONY CHAMBER PLAYERS Sunday, October 22, 2000, at 3 p.m. at Jordan Hall BOSTON SYMPHONY CHAMBER PLAYERS Malcolm Lowe, violin Richard Svoboda, bassoon Steven Ansell, viola James Sommerville, horn Jules Eskin, cello Charles Schlueter, trumpet Edwin Barker, double bass Ronald Barron, trombone Jacques Zoon, flute Everett Firth, percussion William R. Hudgins, clarinet with JAYNE WEST, soprano HALDAN MARTINSON, violin MARTHA BABCOCK, cello STEPHEN DRURY, piano COPLAND As It Fell Upon a Day, for soprano, flute, and clarinet Ms. WEST, Mr. ZOON, and Mr. HUDGINS Threnodies I and II, for flute and string trio Mr. ZOON, Mr. LOWE, Mr. ANSELL, and Ms. BABCOCK Sextet for clarinet, piano, and string quartet Allegro vivace Lento Finale Mr. HUDGINS, Mr. DRURY; Mr. LOWE, Mr. MARTINSON, Mr. ANSELL, and Ms. BABCOCK The Copland performances in this concert celebrate the centennial of Aaron Copland's birth* INTERMISSION BEETHOVEN Septet in E-flat for clarinet, horn, bassoon, violin, viola, cello, and double bass, Opus 20 Adagio—Allegro con brio Adagio cantabile Tempo di menuetto Tema con variazioni: Andante Scherzo: Allegro molto e vivace Andante con moto alia marcia—Presto Baldwin piano Nonesuch, DG, Philips, RCA, and New World records NOTES ON THE PROGRAM AARON COPLAND (November 14, 1900-December 2, 1990) To many listeners, Aaron Copland was the epitome and fountainhead of American music. While Copland was studying with Nadia Boulanger in France, Boulanger introduced him in the spring of 1923 to her friend Serge Koussevitzky, who was soon to become the new conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Koussevitzky and Copland hit it off at once. -

I. ARNOLD SCHOENBERG: Violin Pha!1Tasy, Op. L:·7 (19L~9) the Violin Phantasy, a Work Typical of Schoenberg's Last Years, Is Ostensibly a Virtuoso Piece

e TIlE CONTEMPORARY GROUP November 29, 1967 CONCERT NOTES - I. ARNOLD SCHOENBERG: Violin Pha!1tasy, Op. l:·7 (19l~9) The Violin Phantasy, a work typical of Schoenberg's last years, is ostensibly a virtuoso piece. Its audience appeal is unmistakeable; this immediate attract iveness, however, masks the tight-knit craftsmanship displayed in every measure. Schoenberg lived long enough to see his twelve-tone system accepted and adopted as the musical language of the future. In the Violin Phantasy he refined his doctrine still more: This is an early example of serial hexachords, in which four interrelated sets of six notes form the foundation of the entire work. This style of composition bears a resemblance to Medieval and Renaissance practice. Each six-note group (hexachord) assumes the character of a mode, and the harmonic move ment is subtle and continuous. Schoenberg's formal structure, by contrast, is quite obvious. Phrase-lengths, cadences, and dynamic/textural contrasts are in the classic language of Mozart or r- Beethoven. The first half of the work is based on the violin motives of the first m~nsure - a repeated note (short, long) and a fast three note ascending figure. Thz second half is a lively scherzo reminiscent of Viennese dance music. The Phantasy ends dramatically t<lith a restatement of the opening measures. II. JOHN VERRALL: Symphony for Chamber Orchestra (1967) John Verrall's Symphony for Chanber Orchestra, which tonight receives its pre:::;<i~:re performance, is tailored to the University of tfashington Contemporary Group. E':ery n:ember is employed, and each part is independent. -

Program Notes

with the NASHVILLESYMPHONY CLASSICAL SERIES THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 21, AT 7 PM | FRIDAY & SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 22 & 23, AT 8 PM NASHVILLE SYMPHONY GIANCARLO GUERRERO, conductor CONCERT PARTNER ALBAN GERHARDT, cello AARON JAY KERNIS Symphony No. 4, “Chromelodeon” Out of Silence Thorn, Rose | Weep, Freedom (after Handel) Fanfare Chromelodia SAMUEL BARBER This weekend's performances are made Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 22 possible through the generosity of Allegro moderato Drs. Mark & Nancy Peacock. Andante sostenuto Molto allegro ed appassionato Alban Gerhardt, cello – INTERMISSION – LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 Poco sostenuto – Vivace Allegretto Presto Allegro con brio This concert will last 1 hour and 55 miutes, including a 20-minute intermission. INCONCERT 33 TONIGHT’S CONCERT AT A GLANCE AARON JAY KERNIS Symphony No. 4, “Chromelodeon” • New York City-based composer Kernis has earned the Pulitzer Prize in Music and the prestigious Grawemeyer Award, as well a 2019 GRAMMY® nomination for Best Contemporary Classical Composition. (Winners had not yet been announced at the time of the program guide’s printing.) He also serves as workshop director for the Nashville Symphony’s Composer Lab & Workshop. • The title of his latest symphony, “Chromelodeon,” comes from an unusual word previously used by maverick American composer Harry Partch to describe one of his musical inventions. As defined by the composer, this word aptly describes his own creation here: “chromatic, colorful, melodic music performed by an orchestra.” • The idea of color is especially significant in Kernis’ work, as the composer has synesthesia, a condition that associates specific notes and chords and with distinct colors. -

PROGRAM NOTES Igor Stravinsky Concerto for Piano and Wind

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Igor Stravinsky Born June 18, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia. Died April 6, 1971, New York City. Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments Stravinsky began this piano concerto in the summer of 1923 and completed it on April 21, 1924; he was the soloist at the first performance, conducted by Serge Koussevitzky, on May 22, 1924, in Paris. The orchestra consists of two flutes and piccolo, two oboes and english horn, two clarinets, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, and double basses. Performance time is approximately twenty minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Stravinsky’s Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments were given at Orchestra Hall on January 30 and 31, 1935, with Jane Anderson and Jean Williams as soloists (the work was performed twice; once before and once after intermission) and Eric DeLamarter conducting. Stravinsky himself conducted the work at Orchestra Hall on November 7 and 8, 1940, with Jane Anderson as soloist. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on March 3, 4, 5, and 8, 2005, with Pierre-Laurent Aimard as soloist and David Robertson conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on July 10, 1993, with Peter Serkin as soloist and Libor Pešek conducting. Stravinsky would offer a handful of ways to define the word “concerto” before his career was over. This work for piano and winds was the first, and it was followed by pieces that look back as far as the eighteenth-century concerto grosso and others that help us to hear the original meaning of the word (from the Italian concertare, to join together, and the Latin concertare, to fight or contend) in new ways. -

World Premieres Composer Work Date Conductor Loder Concert Overture, Marmion 17-Jan 1846 Loder Bristow Concert Overture, Op

World Premieres Composer Work Date Conductor Loder Concert Overture, Marmion 17-Jan 1846 Loder Bristow Concert Overture, Op. 3 9-Jan 1847 Timm Bristow Symphony No. 4, Arcadian 14-Feb 1874 Bergmann Liszt Symphonic Poem No. 2, Tasso: 24-Mar 1877 L.Damrosch lamento e trionfo Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2 12-Nov 1881 Thomas R. Strauss Symphony in F minor, Op. 12 13-Dec 1884 Thomas *Lalo Arlequin 28-Nov 1892 W. Damrosch Beach Scena and Aria from Mary Stuart 2-Dec 1892 W.Damrosch Dvořák Symphony No. 9, From the New 16-Dec 1893 Seidl World (formerly No. 5) Herbert Cello Concerto No. 2 9-Mar 1894 Seidl Hadley Symphony No. 2, The Four Seasons 21-Dec 1901 Paur Burmeister Dramatic Tone Poem, The Sisters 10-Jan 1902 Paur Rezniček Donna Dianna 23-Nov 1907 W. Damrosch Lyapunov Concerto for Piano and Orchestra 7-Dec 1907 W. Damrosch Hofmann Concerto for Pianoforte No. 3 28-Feb 1908 Safonoff *Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 3 28-Nov 1909 W.Damrosch *W. Damrosch Excerpt from Canterbury Pilgrims 20-Feb 1910 W.Damrosch *Wallace Symphonic Poem, François Villon 6-Nov 1910 W.Damrosch Busoni Berceuse élégiaque 21-Feb 1911 Mahler *Kolar Symphonic Poem, Hiawatha 12-Mar 1911 Damrosch Laucella Symphonic Poem, Consalvo 26-Nov 1911 Stransky Van der Pals Two Symphonic Pieces 17-Dec 1911 Stransky *W. Damrosch Ballad, The Looking Glass 31-Dec 1911 W.Damrosch *W. Damrosch Juanita's Song from Dove of Peace 31-Dec 1911 W.Damrosch *Wolf "Fairy Song" from A Midsummer 2-Feb 1912 Harris Night's Dream Stahlberg Two Symphonic Sketches from Im 4-Feb 1912 W.Damrosch Hochland *Wolf-Ferrari Two Intermezzi from Jewels of 11-Feb 1912 W.Damrosch Madonna *Handel/Reger Concerto Grosso No. -

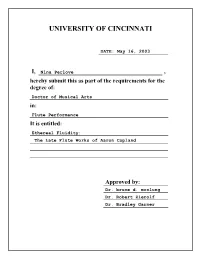

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: May 16, 2003 I, Nina Perlove , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Flute Performance It is entitled: Ethereal Fluidity: The Late Flute Works of Aaron Copland Approved by: Dr. bruce d. mcclung Dr. Robert Zierolf Dr. Bradley Garner ETHEREAL FLUIDITY: THE LATE FLUTE WORKS OF AARON COPLAND A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS (DMA) in the Division of Performance Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Nina Perlove B.M., University of Michigan, 1995 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 1999 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Aaron Copland’s final compositions include two chamber works for flute, the Duo for Flute and Piano (1971) and Threnodies I and II (1971 and 1973), all written as memorial tributes. This study will examine the Duo and Threnodies as examples of the composer’s late style with special attention given to Copland’s tendency to adopt and reinterpret material from outside sources and his desire to be liberated from his own popular style of the 1940s. The Duo, written in memory of flutist William Kincaid, is a representative example of Copland’s 1940s popular style. The piece incorporates jazz, boogie-woogie, ragtime, hymnody, Hebraic chant, medieval music, Russian primitivism, war-like passages, pastoral depictions, folk elements, and Indian exoticisms. The piece also contains a direct borrowing from Copland’s film scores The North Star (1943) and Something Wild (1961).