The Status of Graceful Felt Lichen (Erioderma Mollissimum)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pannariaceae Generic Taxonomy LL Ver. 27.9.2013.Docx

http://www.diva-portal.org Preprint This is the submitted version of a paper published in The Lichenologist. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Ekman, S. (2014) Extended phylogeny and a revised generic classification of the Pannariaceae (Peltigerales, Ascomycota). The Lichenologist, 46: 627-656 http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S002428291400019X Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nrm:diva-943 Extended phylogeny and a revised generic classification of the Pannariaceae (Peltigerales, Ascomycota) Stefan EKMAN, Mats WEDIN, Louise LINDBLOM & Per M. JØRGENSEN S. Ekman (corresponding author): Museum of Evolution, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 16, SE –75236 Uppsala, Sweden. Email: [email protected] M. Wedin: Dept. of Botany, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, SE –10405 Stockholm, Sweden. L. Lindblom and P. M. Jørgensen: Dept. of Natural History, University Museum of Bergen, Box 7800, NO –5020 Bergen, Norway. Abstract: We estimated phylogeny in the lichen-forming ascomycete family Pannariaceae. We specifically modelled spatial (across-site) heterogeneity in nucleotide frequencies, as models not incorporating this heterogeneity were found to be inadequate for our data. Model adequacy was measured here as the ability of the model to reconstruct nucleotide diversity per site in the original sequence data. A potential non-orthologue in the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) of Degelia plumbea was observed. We propose a revised generic classification for the Pannariaceae, accepting 30 genera, based on our phylogeny, previously published phylogenies, as well as morphological and chemical data available. -

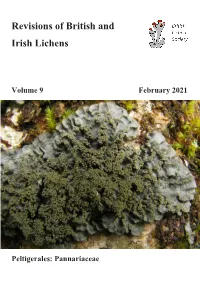

Revisions of British and Irish Lichens

Revisions of British and Irish Lichens Volume 9 February 2021 Peltigerales: Pannariaceae Cover image: Pectenia atlantica, on bark of Fraxinus excelsior, Strath Croe, Kintail, Wester Ross. Revisions of British and Irish Lichens is a free-to-access serial publication under the auspices of the British Lichen Society, that charts changes in our understanding of the lichens and lichenicolous fungi of Great Britain and Ireland. Each volume will be devoted to a particular family (or group of families), and will include descriptions, keys, habitat and distribution data for all the species included. The maps are based on information from the BLS Lichen Database, that also includes data from the historical Mapping Scheme and the Lichen Ireland database. The choice of subject for each volume will depend on the extent of changes in classification for the families concerned, and the number of newly recognized species since previous treatments. To date, accounts of lichens from our region have been published in book form. However, the time taken to compile new printed editions of the entire lichen biota of Britain and Ireland is extensive, and many parts are out-of-date even as they are published. Issuing updates as a serial electronic publication means that important changes in understanding of our lichens can be made available with a shorter delay. The accounts may also be compiled at intervals into complete printed accounts, as new editions of the Lichens of Great Britain and Ireland. Editorial Board Dr P.F. Cannon (Department of Taxonomy & Biodiversity, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Surrey TW9 3AB, UK). Dr A. Aptroot (Laboratório de Botânica/Liquenologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Avenida Costa e Silva s/n, Bairro Universitário, CEP 79070-900, Campo Grande, MS, Brazil) Dr B.J. -

H. Thorsten Lumbsch VP, Science & Education the Field Museum 1400

H. Thorsten Lumbsch VP, Science & Education The Field Museum 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive Chicago, Illinois 60605 USA Tel: 1-312-665-7881 E-mail: [email protected] Research interests Evolution and Systematics of Fungi Biogeography and Diversification Rates of Fungi Species delimitation Diversity of lichen-forming fungi Professional Experience Since 2017 Vice President, Science & Education, The Field Museum, Chicago. USA 2014-2017 Director, Integrative Research Center, Science & Education, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. Since 2014 Curator, Integrative Research Center, Science & Education, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. 2013-2014 Associate Director, Integrative Research Center, Science & Education, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. 2009-2013 Chair, Dept. of Botany, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. Since 2011 MacArthur Associate Curator, Dept. of Botany, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. 2006-2014 Associate Curator, Dept. of Botany, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. 2005-2009 Head of Cryptogams, Dept. of Botany, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. Since 2004 Member, Committee on Evolutionary Biology, University of Chicago. Courses: BIOS 430 Evolution (UIC), BIOS 23410 Complex Interactions: Coevolution, Parasites, Mutualists, and Cheaters (U of C) Reading group: Phylogenetic methods. 2003-2006 Assistant Curator, Dept. of Botany, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. 1998-2003 Privatdozent (Assistant Professor), Botanical Institute, University – GHS - Essen. Lectures: General Botany, Evolution of lower plants, Photosynthesis, Courses: Cryptogams, Biology -

Habitat Quality and Disturbance Drive Lichen Species Richness in a Temperate Biodiversity Hotspot

Oecologia (2019) 190:445–457 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-019-04413-0 COMMUNITY ECOLOGY – ORIGINAL RESEARCH Habitat quality and disturbance drive lichen species richness in a temperate biodiversity hotspot Erin A. Tripp1,2 · James C. Lendemer3 · Christy M. McCain1,2 Received: 23 April 2018 / Accepted: 30 April 2019 / Published online: 15 May 2019 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract The impacts of disturbance on biodiversity and distributions have been studied in many systems. Yet, comparatively less is known about how lichens–obligate symbiotic organisms–respond to disturbance. Successful establishment and development of lichens require a minimum of two compatible yet usually unrelated species to be present in an environment, suggesting disturbance might be particularly detrimental. To address this gap, we focused on lichens, which are obligate symbiotic organ- isms that function as hubs of trophic interactions. Our investigation was conducted in the southern Appalachian Mountains, USA. We conducted complete biodiversity inventories of lichens (all growth forms, reproductive modes, substrates) across 47, 1-ha plots to test classic models of responses to disturbance (e.g., linear, unimodal). Disturbance was quantifed in each plot using a standardized suite of habitat quality variables. We additionally quantifed woody plant diversity, forest density, rock density, as well as environmental factors (elevation, temperature, precipitation, net primary productivity, slope, aspect) and analyzed their impacts on lichen biodiversity. Our analyses recovered a strong, positive, linear relationship between lichen biodiversity and habitat quality: lower levels of disturbance correlate to higher species diversity. With few exceptions, additional variables failed to signifcantly explain variation in diversity among plots for the 509 total lichen species, but we caution that total variation in some of these variables was limited in our study area. -

Lichens and Associated Fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska

The Lichenologist (2020), 52,61–181 doi:10.1017/S0024282920000079 Standard Paper Lichens and associated fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska Toby Spribille1,2,3 , Alan M. Fryday4 , Sergio Pérez-Ortega5 , Måns Svensson6, Tor Tønsberg7, Stefan Ekman6 , Håkon Holien8,9, Philipp Resl10 , Kevin Schneider11, Edith Stabentheiner2, Holger Thüs12,13 , Jan Vondrák14,15 and Lewis Sharman16 1Department of Biological Sciences, CW405, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2R3, Canada; 2Department of Plant Sciences, Institute of Biology, University of Graz, NAWI Graz, Holteigasse 6, 8010 Graz, Austria; 3Division of Biological Sciences, University of Montana, 32 Campus Drive, Missoula, Montana 59812, USA; 4Herbarium, Department of Plant Biology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA; 5Real Jardín Botánico (CSIC), Departamento de Micología, Calle Claudio Moyano 1, E-28014 Madrid, Spain; 6Museum of Evolution, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 16, SE-75236 Uppsala, Sweden; 7Department of Natural History, University Museum of Bergen Allégt. 41, P.O. Box 7800, N-5020 Bergen, Norway; 8Faculty of Bioscience and Aquaculture, Nord University, Box 2501, NO-7729 Steinkjer, Norway; 9NTNU University Museum, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway; 10Faculty of Biology, Department I, Systematic Botany and Mycology, University of Munich (LMU), Menzinger Straße 67, 80638 München, Germany; 11Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK; 12Botany Department, State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, Rosenstein 1, 70191 Stuttgart, Germany; 13Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK; 14Institute of Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Zámek 1, 252 43 Průhonice, Czech Republic; 15Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 1760, CZ-370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic and 16Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve, P.O. -

Species Fact Sheet

SPECIES FACT SHEET Common Name: pink-eyed mouse, shingle lichen. Scientific Name: Fuscopannaria saubinetii (Mont.) P. M. Jørg. Synonym: Pannaria saubinetii (Mont.) Nyl. Division: Ascomycota Class: Lecanoromycetes Order: Peltigerales Family: Pannariaceae Note: This species not found in North America. Previous records misidentifications, most often Fuscopannaria pacifica (see below for details and references). Technical Description: Thallus made of small (to 1 mm diameter), smooth, delicately incised, bluish leaf-like flaps (squamulose). The squamules have an upper cortex, a medulla with the cyanobacteria Nostoc (photobiont) and fungal hyphae, and no lower cortex. Apothecia convex, flesh-colored, to 0.5 mm diam., with a pale margin of fungal tissue (proper margin) but without an obvious ring of thallus-colored tissue around the edge (thalline margin). Hymenium reacts blue-green then turns red-brown rapidly in I. Asci with apical amyloid sheet (this is a microscopic character that takes acquired skill to locate). Spores simple, colorless, ellipsoid, 15- 17x5-6 µm. Other descriptions and illustrations: Jørgensen 1978, Brodo 2001. Chemistry: All spot tests on thallus negative. Distinctive Characters: (1) pale blue-gray, delicately incised squamules with small flesh- colored apothecia, (2) spores 15-17X5-6 µm, (3) asci with amyloid sheet. Similar Species: Many Pannaria and Fuscopannaria species look similar and are very difficult to distinguish. Fuscopannaria pacifica is the species described from North America that is most often confused with F. saubinetii. Fuscopannaria pacifica has squamules that are brownish gray and minutely incised, lying on a black mat of hyphal strands. Its pale orangish brown convex apothecia lack a margin of thallus-colored tissue, the spores are 16-20x7-10 µm, and the asci have amyloid rings instead of an amyloid sheet. -

Lichens of East Limestone Island

Lichens of East Limestone Island Stu Crawford, May 2012 Platismatia Crumpled, messy-looking foliose lichens. This is a small genus, but the Pacific Northwest is a center of diversity for this genus. Out of the six species of Platismatia in North America, five are from the Pacific Northwest, and four are found in Haida Gwaii, all of which are on Limestone Island. Platismatia glauca (Ragbag lichen) This is the most common species of Platismatia, and is the only species that is widespread. In many areas, it is the most abundant lichen. Oddly, it is not the most abundant Platismatia on Limestone Island. It has soredia or isidia along the edges of its lobes, but not on the upper surface like P. norvegica. It also isn’t wrinkled like P. norvegica or P. lacunose. Platismatia norvegica It has large ridges or wrinkles on its surface. These ridges are covered in soredia or isidia, particularly close to the edges of the lobes. In the interior, it is restricted to old growth forests. It is less fussy in coastal rainforests, and really seems to like Limestone Island, where it is the most abundant Platismatia. Platismatia lacunosa (wrinkled rag lichen) This species also has large wrinkles on its surface, like P. norvegica. However, it doesn’t have soredia or isidia on top of these ridges. Instead, it has tiny black dots along the edges of its lobes which produce spores. It is also usually whiter than P. lacunosa. It is less common on Limestone Island. Platismatia herrei (tattered rag lichen) This species looks like P. -

Extended Phylogeny and a Revised Generic Classification of The

The Lichenologist 46(5): 627–656 (2014) 6 British Lichen Society, 2014 doi:10.1017/S002428291400019X Extended phylogeny and a revised generic classification of the Pannariaceae (Peltigerales, Ascomycota) Stefan EKMAN, Mats WEDIN, Louise LINDBLOM and Per M. JØRGENSEN Abstract: We estimated phylogeny in the lichen-forming ascomycete family Pannariaceae. We specif- ically modelled spatial (across-site) heterogeneity in nucleotide frequencies, as models not incorpo- rating this heterogeneity were found to be inadequate for our data. Model adequacy was measured here as the ability of the model to reconstruct nucleotide diversity per site in the original sequence data. A potential non-orthologue in the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) of Degelia plumbea was observed. We propose a revised generic classification for the Pannariaceae, accepting 30 genera, based on our phylogeny, previously published phylogenies, as well as available morphological and chemical data. Four genera are established as new: Austroparmeliella (for the ‘Parmeliella’ lacerata group), Nebularia (for the ‘Parmeliella’ incrassata group), Nevesia (for ‘Fuscopannaria’ sampaiana), and Pectenia (for the ‘Degelia’ plumbea group). Two genera are reduced to synonymy, Moelleropsis (included in Fuscopannaria) and Santessoniella (non-monophyletic; type included in Psoroma). Lepido- collema, described as monotypic, is expanded to include 23 species, most of which have been treated in the ‘Parmeliella’ mariana group. Homothecium and Leightoniella, previously treated in the Collemataceae, are here referred to the Pannariaceae. We propose 41 new species-level combinations in the newly described and re-circumscribed genera mentioned above, as well as in Leciophysma and Psoroma. Key words: Collemataceae, lichen taxonomy, model adequacy, model selection Accepted for publication 13 March 2014 Introduction which include c. -

Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Biogeography of the Lichen Genus Peltigera in Papua New Guinea

Fungal Diversity Taxonomy, phylogeny and biogeography of the lichen genus Peltigera in Papua New Guinea Sérusiaux, E.1*, Goffinet, B.2, Miadlikowska, J.3 and Vitikainen, O.4 1Plant Taxonomy and Conservation Biology Unit, University of Liège, Sart Tilman B22, B-4000 Liège, Belgium 2Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, 75 North Eagleville Road, Storrs CT 06269-3043 USA 3Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0338, USA 4Botanical Museum (Mycology), P.O. Box 7, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Sérusiaux, E., Goffinet, B., Miadlikowska, J. and Vitikainen, O. (2009). Taxonomy, phylogeny and biogeography of the the lichen genus Peltigera in Papua New Guinea. Fungal Diversity 38: 185-224. The lichen genus Peltigera is represented in Papua New Guinea by 15 species, including 6 described as new for science: P. cichoracea, P. didactyla, P. dolichorhiza, P. erioderma, P. extenuata, P. fimbriata sp. nov., P. granulosa sp. nov., P. koponenii sp. nov., P. montis-wilhelmii sp. nov., P. nana, P. oceanica, P. papuana sp. nov., P. sumatrana, P. ulcerata, and P. weberi sp. nov. Peltigera macra and P. tereziana var. philippinensis are reduced to synonymy with P. nana, whereas P. melanocoma is maintained as a species distinct from P. nana pending further studies. The status of several putative taxa referred to P. dolichorhiza s. lat. in the Sect. Polydactylon remains to be studied on a wider geographical scale and in the context of P. dolichorhiza and P. neopolydactyla. The phylogenetic affinities of all but one regional species (P. extenuata) are studied based on inferences from ITS (nrDNA) sequence data, in the context of a broad taxonomic sampling within the genus. -

Boreal Felt Lichen (Erioderma Pedicellatum) Is a Globally Threatened, Conspicuous Foliose Cyanolichen Belonging to the Pannariaceae

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Boreal Felt Lichen Erioderma pedicellatum Atlantic population Boreal population in Canada ENDANGERED - Atlantic population 2002 SPECIAL CONCERN - Boreal population 2002 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION DES ENDANGERED WILDLIFE IN ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: Please note: Persons wishing to cite data in the report should refer to the report (and cite the author(s)); persons wishing to cite the COSEWIC status will refer to the assessment (and cite COSEWIC). A production note will be provided if additional information on the status report history is required. COSEWIC 2002. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the boreal felt lichen Erioderma pedicellatum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. viii + 50 pp. Maass, W. and D. Yetman. 2002. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the boreal felt lichen Erioderma pedicellatum in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the boreal felt lichen Erioderma pedicellatum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1- 50 pp. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Ếgalement disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport du COSEPAC sur la situation de l’erioderme boréal (Erioderma pedicellatum) au Canada Cover illustration: Boreal felt lichen — Provided by the author, photo by Dr. -

Piedmont Lichen Inventory

PIEDMONT LICHEN INVENTORY: BUILDING A LICHEN BIODIVERSITY BASELINE FOR THE PIEDMONT ECOREGION OF NORTH CAROLINA, USA By Gary B. Perlmutter B.S. Zoology, Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA 1991 A Thesis Submitted to the Staff of The North Carolina Botanical Garden University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Advisor: Dr. Johnny Randall As Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Certificate in Native Plant Studies 15 May 2009 Perlmutter – Piedmont Lichen Inventory Page 2 This Final Project, whose results are reported herein with sections also published in the scientific literature, is dedicated to Daniel G. Perlmutter, who urged that I return to academia. And to Theresa, Nichole and Dakota, for putting up with my passion in lichenology, which brought them from southern California to the Traingle of North Carolina. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………….4 Chapter I: The North Carolina Lichen Checklist…………………………………………………7 Chapter II: Herbarium Surveys and Initiation of a New Lichen Collection in the University of North Carolina Herbarium (NCU)………………………………………………………..9 Chapter III: Preparatory Field Surveys I: Battle Park and Rock Cliff Farm……………………13 Chapter IV: Preparatory Field Surveys II: State Park Forays…………………………………..17 Chapter V: Lichen Biota of Mason Farm Biological Reserve………………………………….19 Chapter VI: Additional Piedmont Lichen Surveys: Uwharrie Mountains…………………...…22 Chapter VII: A Revised Lichen Inventory of North Carolina Piedmont …..…………………...23 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………..72 Appendices………………………………………………………………………………….…..73 Perlmutter – Piedmont Lichen Inventory Page 4 INTRODUCTION Lichens are composite organisms, consisting of a fungus (the mycobiont) and a photosynthesising alga and/or cyanobacterium (the photobiont), which together make a life form that is distinct from either partner in isolation (Brodo et al. -

Cyanobacteria Produce a High Variety of Hepatotoxic Peptides in Lichen Symbiosis

Cyanobacteria produce a high variety of hepatotoxic peptides in lichen symbiosis Ulla Kaasalainena,1, David P. Fewerb, Jouni Jokelab, Matti Wahlstenb, Kaarina Sivonenb, and Jouko Rikkinena aDepartment of Biosciences and bDepartment of Food and Environmental Sciences, Division of Microbiology, University of Helsinki, FIN-00014, Helsinki, Finland Edited by Robert Haselkorn, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and approved February 28, 2012 (received for review January 6, 2012) Lichens are symbiotic associations between fungi and photosyn- freshwater ecosystems. We have previously shown that the Nostoc thetic algae or cyanobacteria. Microcystins are potent toxins that symbionts of the tripartite cyanolichen species Peltigera leuco- are responsible for the poisoning of both humans and animals. phlebia can produce hepatotoxic microcystins in lichen symbiosis These toxins are mainly associated with aquatic cyanobacterial (11). However, it was unclear whether the production of these blooms, but here we show that the cyanobacterial symbionts of potent hepatotoxins in lichen symbiosis is a frequent phenome- terrestrial lichens from all over the world commonly produce non. Here we report that microcystins and nodularins are pro- microcystins. We screened 803 lichen specimens from five different duced in many different cyanolichen lineages and climatic regions continents for cyanobacterial toxins by amplifying a part of the all over the world. gene cluster encoding the enzyme complex responsible for micro- cystin production and detecting toxins directly from lichen thalli. We Results found either the biosynthetic genes for making microcystins or the A total of 803 lichen thalli representing 23 different cyanolichen toxin itself in 12% of all analyzed lichen specimens. A plethora of genera from different parts of the world were analyzed (Fig.