A Critical Analysis of UK News Media Representations of Proposals To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Access Wales & U.K. Newspapers

Access Wales & U.K. Newspapers Easy access to local, regional and national news Quick Facts Features more than 25 newspapers from across Wales Includes the major dailies and community newspapers Interface in English or Welsh Overview Designed specifically for libraries in Wales, Access Wales & U.K. Newspapers features popular news sources from within Wales, providing in-depth coverage of local and regional issues and events. Well-known sources from England, Scotland, Northern Ireland are also included, further expanding the scope of this robust research tool. Welsh News This collection of more than 25 Welsh newspapers offers users daily and weekly news sources of interest, including the North Wales edition of the Daily Post, the Western Mail and the South Wales Evening Post. News articles provide detailed coverage of businesses, government, sports, politics, the arts, culture, finance, health, science, education and more – from large and small cities alike. Daily updates keep users informed of the latest developments from the assembly government, farming news, rugby and cricket events, and much more. Retrospective articles - ideal for comparing today’s issues and events with past news - are included, as well. U.K. News This optional collection of more than 500 news sources provides in-depth coverage of issues and events within the U.K. and Ireland. Major national broadsides and tabloids are complemented by a list of popular daily, weekly and online news sources, including The Times (1985 forward), Financial Times, The Guardian, and The Scotsman. This robust collection keeps readers and researchers abreast of local and national news, as well as developments in nearby countries that impact life in Wales. -

Sheet1 Page 1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen

Sheet1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen - Press & Journal 71,044 Dundee Courier & Advertiser 61,981 Norwich - Eastern Daily Press 59,490 Belfast Telegraph 59,319 Shropshire Star 55,606 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Evening Chronicle 52,486 Glasgow - Evening Times 52,400 Leicester Mercury 51,150 The Sentinel 50,792 Aberdeen - Evening Express 47,849 Birmingham Mail 47,217 Irish News - Morning 43,647 Hull Daily Mail 43,523 Portsmouth - News & Sports Mail 41,442 Darlington - The Northern Echo 41,181 Teesside - Evening Gazette 40,546 South Wales Evening Post 40,149 Edinburgh - Evening News 39,947 Leeds - Yorkshire Post 39,698 Bristol Evening Post 38,344 Sheffield Star & Green 'Un 37,255 Leeds - Yorkshire Evening Post 36,512 Nottingham Post 35,361 Coventry Telegraph 34,359 Sunderland Echo & Football Echo 32,771 Cardiff - South Wales Echo - Evening 32,754 Derby Telegraph 32,356 Southampton - Southern Daily Echo 31,964 Daily Post (Wales) 31,802 Plymouth - Western Morning News 31,058 Southend - Basildon - Castle Point - Echo 30,108 Ipswich - East Anglian Daily Times 29,932 Plymouth - The Herald 29,709 Bristol - Western Daily Press 28,322 Wales - The Western Mail - Morning 26,931 Bournemouth - The Daily Echo 26,818 Bradford - Telegraph & Argus 26,766 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Journal 26,280 York - The Press 25,989 Grimsby Telegraph 25,974 The Argus Brighton 24,949 Dundee Evening Telegraph 23,631 Ulster - News Letter 23,492 South Wales Argus - Evening 23,332 Lancashire Telegraph - Blackburn 23,260 -

National Library of Ireland

ABOUT TOWN (DUNGANNON) AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) No. 1, May - Dec. 1986 Feb. 1950- April 1951 Jan. - June; Aug - Dec. 1987 Continued as Jan.. - Sept; Nov. - Dec. 1988 AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Jan. - Aug; Oct. 1989 May 1951 - Dec. 1971 Jan, Apr. 1990 April 1972 - April 1975 All Hardcopy All Hardcopy Misc. Newspapers 1982 - 1991 A - B IL B 94109 ADVERTISER (WATERFORD) AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Mar. 11 - Sept. 16, 1848 - Microfilm See AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) ADVERTISER & WATERFORD MARKET NOTE ALLNUTT'S IRISH LAND SCHEDULE (WATERFORD) (DUBLIN) March 4 - April 15, 1843 - Microfilm No. 9 Jan. 1, 1851 Bound with NATIONAL ADVERTISER Hardcopy ADVERTISER FOR THE COUNTIES OF LOUTH, MEATH, DUBLIN, MONAGHAN, CAVAN (DROGHEDA) AMÁRACH (DUBLIN) Mar. 1896 - 1908 1956 – 1961; - Microfilm Continued as 1962 – 1966 Hardcopy O.S.S. DROGHEDA ADVERTISER (DROGHEDA) 1967 - May 13, 1977 - Microfilm 1909 - 1926 - Microfilm Sept. 1980 – 1981 - Microfilm Aug. 1927 – 1928 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1982 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1929 - Microfilm 1983 - Microfilm Incorporated with DROGHEDA ARGUS (21 Dec 1929) which See. - Microfilm ANDERSONSTOWN NEWS (ANDERSONSTOWN) Nov. 22, 1972 – 1993 Hardcopy O.S.S. ADVOCATE (DUBLIN) 1994 – to date - Microfilm April 14, 1940 - March 22, 1970 (Misc. Issues) Hardcopy O.S.S. ANGLO CELT (CAVAN) Feb. 6, 1846 - April 29, 1858 ADVOCATE (NEW YORK) Dec. 10, 1864 - Nov. 8, 1873 Sept. 23, 1939 - Dec. 25th, 1954 Jan. 10, 1885 - Dec. 25, 1886 Aug. 17, 1957 - Jan. 11, 1958 Jan. 7, 1887 - to date Hardcopy O.S.S. (Number 5) All Microfilm ADVOCATE OR INDUSTRIAL JOURNAL ANOIS (DUBLIN) (DUBLIN) Sept. 2, 1984 - June 22, 1996 - Microfilm Oct. 28, 1848 - Jan 1860 - Microfilm ANTI-IMPERIALIST (DUBLIN) AEGIS (CASTLEBAR) Samhain 1926 June 23, 1841 - Nov. -

Implementing Trinity Mirror's Online Strategy

Supplementary memorandum submitted by the NUJ (Glob 21a) Turning Around the Tanker: Implementing Trinity Mirror’s Online Strategy Dr. Andrew Williams and Professor Bob Franklin The School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies, Cardiff University Executive Summary The UK local and regional newspaper industry presents a paradox. On “Why kill the goose the one hand: that laid the golden egg? [...] The goose • Profit margins are very high: almost 19% at Trinity Mirror, and has got bird flu” 38.2% at the Western Mail and Echo in 2005 Michael Hill, Trinity Mirror’s regional head of multimedia on the future of print newspapers • Newspaper advertising revenues are extremely high: £3 billion in 2005, newspapers are the second largest advertising medium in the UK But on the other hand: • Circulations have been declining steeply: 38% drop at Cardiff’s “Pay is a disgrace. Western Mail since 1993, more than half its readers lost since 1979 When you look at • Companies have implemented harsh staffing cuts: 20% cut in levels of pay […] in editorial and production staff at Trinity Mirror, and 31% at relation to other white collar Western Mail and Echo since 1999 professionals of • Journalists’ workloads are incredibly heavy while pay has comparable age remained low: 84% of staff at Western Mail and Echo think their and experience they workload has increased, and the starting wage for a trainee are appallingly journalist is only £11,113 bad”. Western Mail • Reporters rely much more on pre-packaged sources of news like and Echo journalist agencies and PR: 92% of survey respondents claimed they now use more PR copy in stories than previously, 80% said they use the wires more often The move to online Companies like Trinity Mirror will not be able to sustain high profits is like “turning based on advertising revenues because of growing competition from round an oil tanker […] some staff will the internet. -

The Journal of the Association for Journalism Education

Journalism Education ISSN: 2050-3903 Journalism Education The Journal of the Association for Journalism Education Volume Nine, No: One Spring 2020 Page 2 Journalism Education Volume 9 number 1 Journalism Education Journalism Education is the journal of the Association for Journalism Education a body representing educators in HE in the UK and Ireland. The aim of the journal is to promote and develop analysis and understanding of journalism education and of journalism, particu- larly when that is related to journalism education. Editors Sallyanne Duncan, University of Strathclyde Chris Frost, Liverpool John Moores University Deirdre O’Neill Huddersfield University Stuart Allan, Cardiff University Reviews editor: Tor Clark, de Montfort University You can contact the editors at [email protected] Editorial Board Chris Atton, Napier University Olga Guedes Bailey, Nottingham Trent University David Baines, Newcastle University Guy Berger, UNESCO Jane Chapman, University of Lincoln Martin Conboy, Sheffield University Ros Coward, Roehampton University Stephen Cushion, Cardiff University Susie Eisenhuth, University of Technology, Sydney Ivor Gaber, University of Sussex Roy Greenslade, City University Mark Hanna, Sheffield University Michael Higgins, Strathclyde University John Horgan, Ireland Sammye Johnson, Trinity University, San Antonio, USA Richard Keeble, University of Lincoln Mohammed el-Nawawy, Queens University of Charlotte An Duc Nguyen, Bournemouth University Sarah Niblock, CEO UKCP Bill Reynolds, Ryerson University, Canada Ian Richards, -

News Consumption Survey 2019

News Consumption Survey 2019 Wales PROMOTING CHOICE • SECURING STANDARDS • PREVENTING HARM About the News Consumption report 2019 The aim of the News Consumption report is to inform understanding of news consumption across the UK and within each UK nation. This includes sources and platforms used, the perceived importance of different outlets for news, attitudes towards individual news sources, international and local news use. The primary source* is Ofcom’s News Consumption Survey. The survey is conducted using face-to- face and online interviews. In total, 2,156 face-to-face and 2,535 online interviews across the UK were carried out during 2018/19. The interviews were conducted over two waves (November & December and March) in order to achieve a robust and representative view of UK adults. The sample size for all adults over the age of 16 in Wales is 475. The full UK report and details of its methodology can be read here. *The News Consumption 2019 report also contains information from a range of industry currencies including BARB for television viewing, TouchPoints for newspaper readership, ABC for newspaper circulation and Comscore for online consumption. PROMOTING CHOICE • SECURING STANDARDS • PREVENTING HARM 2 Key findings from the 2019 report • TV remains the most-used platform for news nowadays by adults in Wales at 75%, compared to 80% last year. • Social media is the second most used platform for news in Wales (45%) and is used more frequently than any other type of internet news source. • More than half of adults (57%) in Wales use BBC One for news, but this is down from 68% last year. -

BMJ in the News Is a Weekly Digest of BMJ Stories, Plus Any Other News

BMJ in the News is a weekly digest of BMJ stories, plus any other news about the company that has appeared in the national and a selection of English-speaking international media. This week’s (8-14 May) highlights: ● A study in The BMJ reporting heightened risk of heart attacks with common painkillers generated global news headlines, including BBC, CNN and Voice of America ● A rapid recommendations article in The BMJ, advising against surgery for most patients with knee arthritis also made global headlines, including CBS and National Public Radio (NPR) in the US ● A warning by doctors in BMJ Case Reports of parasites in raw and undercooked fish generated global headlines, including BBC, Newsweek, CNN and Hindustan Times ● Dr Krishna Chinthapalli was interviewed on Channel 4 News, Sky News, and BBC about this weekend’s cyberattack after warning in The BMJ that hospitals must be better prepared The BMJ Awards Birch's life-saver wins a top award [print only] - Leicester Mercury, 10/05/2017 The BMJ Analysis: Medicalising unhappiness: new classification of depression risks more patients being put on drug treatment from which they will not benefit Fluctuating emotions are part of sport, they must not cloud mental health debate - The Times + The Times Scotland [The Game] 08/05/2017 Trump, the doctor and the vaccine scandal [mentions The BMJ’s articles accusing Andrew Wakefield of fraud] - Channel 4 Dispatches 08/05/2017 Why on earth are so many broken bones not spotted in casualty? - Daily Mail -

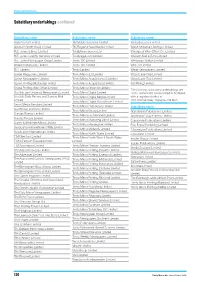

Subsidiary Undertakings Continued

Financial Statements Subsidiary undertakings continued Subsidiary name Subsidiary name Subsidiary name Planetrecruit Limited TM Mobile Solutions Limited Websalvo.com Limited Quids-In (North West) Limited TM Regional New Media Limited Welsh Universal Holdings Limited R.E. Jones & Bros. Limited Totallyfinancial.com Ltd Welshpool Web-Offset Co. Limited R.E. Jones Graphic Services Limited Totallylegal.com Limited Western Mail & Echo Limited R.E. Jones Newspaper Group Limited Trinity 100 Limited Whitbread Walker Limited Reliant Distributors Limited Trinity 102 Limited Wire TV Limited RH1 Limited Trinity Limited Wirral Newspapers Limited Scene Magazines Limited Trinity Mirror (L I) Limited Wood Lane One Limited Scene Newspapers Limited Trinity Mirror Acquisitions (2) Limited Wood Lane Two Limited Scene Printing (Midlands) Limited Trinity Mirror Acquisitions Limited Workthing Limited Scene Printing Web Offset Limited Trinity Mirror Cheshire Limited The following subsidiary undertakings are Scottish and Universal Newspapers Limited Trinity Mirror Digital Limited 100% owned and incorporated in Scotland, Scottish Daily Record and Sunday Mail Trinity Mirror Digital Media Limited with a registered office at Limited One Central Quay, Glasgow, G3 8DA. Trinity Mirror Digital Recruitment Limited Smart Media Services Limited Trinity Mirror Distributors Limited Subsidiary name Southnews Trustees Limited Trinity Mirror Group Limited Aberdonian Publications Limited Sunday Brands Limited Trinity Mirror Huddersfield Limited Anderston Quay Printers Limited Sunday -

Cotwsupplemental Appendix Fin

1 Supplemental Appendix TABLE A1. IRAQ WAR SURVEY QUESTIONS AND PARTICIPATING COUNTRIES Date Sponsor Question Countries Included 4/02 Pew “Would you favor or oppose the US and its France, Germany, Italy, United allies taking military action in Iraq to end Kingdom, USA Saddam Hussein’s rule as part of the war on terrorism?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 8-9/02 Gallup “Would you favor or oppose sending Canada, Great Britain, Italy, Spain, American ground troops (the United States USA sending ground troops) to the Persian Gulf in an attempt to remove Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 9/02 Dagsavisen “The USA is threatening to launch a military Norway attack on Iraq. Do you consider it appropriate of the USA to attack [WITHOUT/WITH] the approval of the UN?” (Figures represent average across the two versions of the UN approval question wording responding “under no circumstances”) 1/03 Gallup “Are you in favor of military action against Albania, Argentina, Australia, Iraq: under no circumstances; only if Bolivia, Bosnia, Bulgaria, sanctioned by the United Nations; Cameroon, Canada, Columbia, unilaterally by America and its allies?” Denmark, Ecuador, Estonia, (Figures represent percent responding “under Finland, France, Georgia, no circumstances”) Germany, Iceland, India, Ireland, Kenya, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malaysia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, Portugal, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Uganda, United Kingdom, USA, Uruguay 1/03 CVVM “Would you support a war against Iraq?” Czech Republic (Figures represent percent responding “no”) 1/03 Gallup “Would you personally agree with or oppose Hungary a US military attack on Iraq without UN approval?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 2 1/03 EOS-Gallup “For each of the following propositions tell Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, me if you agree or not. -

7 Shocking Local News Industry Trends Which Should Terrify You

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru / National Assembly for Wales Pwyllgor Diwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chyfathrebu / The Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee Newyddiaduraeth Newyddion yng Nghymru / News Journalism in Wales CWLC(5) NJW10 Ymateb gan Dr. Andy Williams, Prifysgol Caerdydd / Evidence from Dr. Andy Williams, Cardiff University 7 shocking local news industry trends which should terrify you. The withdrawal of established journalism from Welsh communities and its effects on public interest reporting. In the first of two essays about local news in Wales, I draw on Welsh, UK, and international research, published company accounts, trade press coverage, and first-hand testimony about changes to the economics, journalistic practices, and editorial priorities of established local media. With specific reference to the case study of Media Wales (and its parent company Trinity Mirror) I provide an evidence-based and critical analysis which charts both the steady withdrawal of established local journalism from Welsh communities and the effects of this retreat on the provision of accurate and independent local news in the public interest. A second essay, also submitted as evidence to this committee, explores recent research about the civic and democratic value of a new generation of (mainly online) community news producers. Local newspapers are in serious (and possibly terminal) decline In 1985 Franklin found 1,687 local newspapers in the UK (including Sunday and free titles); by 2005 this had fallen by almost a quarter to 1,286 (Franklin 2006b). By 2015 the figure stood at 1,100, a 35% drop over 30 years, with a quarter of those lost being paid-for newspapers (Ramsay and Moore 2016). -

Coercive Control in Domestic Relationships

Submission No 109 COERCIVE CONTROL IN DOMESTIC RELATIONSHIPS Name: Professor Marilyn McMahon and Mr Paul McGorrery Position: Deputy Dean Date Received: 3 February 2021 3 February 2021 Natalie Ward MP Chair, Joint Select Committee on Coercive Control CC: Trish Doyle MP (Deputy Chair) Abigail Boyd MP (Member) Justin Clancy MP (Member) Steph Cooke MP (Member) Rod Roberts MP (Member) Peter Sidgreaves MP (Member) Anna Watson MP (Member) Dear Ms Ward and Committee Members, RE: CRIMINALISING COERCIVE CONTROL IN NSW Thank you for the invitation to make a submission in response to the discussion paper published in October 2020 about whether NSW criminal law should be extended to capture what is now commonly referred to as coercive control. The discussion paper discusses a broad range of issues. There are no doubt many reforms across the criminal law and related areas that would benefit from review in light of our contemporary understanding of domestic abuse. Our submission is, however, limited to the issue of whether a new, standalone offence should be enacted to criminalise the behaviours known as ‘coercive control.’ We understand the term ‘coercive control’ to refer to a pattern of control and domination in a domestic relationship that can include verbal, economic and psychological abuse, as well as sexual and physical violence. The term is commonly associated with the work of Evan Stark but should not be dependent on that single stream of research and advocacy. The issue of criminalising ‘coercive control’ is significant because many of these abusive behaviours are not yet criminalised, and those that are directly or indirectly criminalised do not adequately recognise the harms caused and/or are difficult to enforce. -

Gwynedd Archives, Caernarfon Record Office

GB0219XM 6233, XM2830 Gwynedd Archives, Caernarfon Record Office This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 37060 The National Archives GWYNEDD ARCHIVES AND MUSEUMS SERVICE Caernarfon Record Office Name of group/collection Group reference code: XM Papers of Mr. J.H. Roberts, AelyBryn, Caernarfon, newpaper reporter (father of the donors); Mr. Roberts was the Caernarfon and district representative of the Liverpool Evening Express and the Daily Post. He had also worked on the staff of the Genedl Gymreig and the North Wales Observer and Express. He was the official shorthand writer for the Caernarfon Assizes and the Quarter Sessions. Shorthand notebooks of Mr. 3.H. Roberts containing notes on: 'Reign of Common People' by H. Ward Beecher at Caernarvon, 20 Aug. 1886. Caernarvon Board of Guardians, 21 Aug. 1886. Caernarvon Borough Court, 23 Aug. 1886 Caernarvon Town Council (Special Meeting) 24 Aug. 1886. Methodists' Association at Bangor, 25-26 Aug. 1886 Quarrymen's Meeting, Bethesda, 3 Sept. 1886. ' Caernarvon Board of Guardians, 4 Sept. 1886 Bangor City Council, 6 Sept. 1886. Bangor Parliamentary Debating Society - Reports of Debates, 1886: Nov. 26 - Adjourned Queen's Speech. Dec. 10 - Adjourned Queen's Speech Government Inquiry at Conway to the Tithed Riots at Mochdre and other places before 3. Bridge, a Metropolitan magistrate. Professor 3ohn Rhys acting as Secretary and interpreter, 26-28 3uly, 1887. Interview with Col. West (agent of Penrhyn Estate, 1887). Liberal meeting on Irish Question at Bangor. 1 Class Mark XM/6233 XS/2830 Sunday Closing Commission at Bangor 1889.