Thriving in Crisis: the Chick Webb Orchestra and the Great Depression”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the DRUMS of Chick Webb

1 The DRUMS of WILLIAM WEBB “CHICK” Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: Feb. 16, 2021 2 Born: Baltimore, Maryland, Feb. 10, year unknown, 1897, 1902, 1905, 1907 and 1909 have been suggested (ref. Mosaic’s Chick Webb box) Died: John Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, June 16, 1939 Introduction: We loved Chick Webb back then in Oslo Jazz Circle. And we hated Ella Fitzgerald because she sung too much; even took over the whole thing and made so many boring records instead of letting the band swing, among the hottest jazz units on the swing era! History: Overcame physical deformity caused by tuberculosis of the spine. Bought first set of drums from his earnings as a newspaper boy. Joined local boys’ band at the age of 11, later (together with John Trueheart) worked in the Jazzola Orchestra, playing mainly on pleasure steamers. Moved to New York (ca. 1925), subsequently worked briefly in Edgar Dowell’s Orchestra. In 1926 led own five- piece band at The Black Bottom Club, New York, for five-month residency. Later led own eight-piece band at the Paddocks Club, before leading own ‘Harlem Stompers’ at Savoy Ballroom from January 1927. Added three more musicians for stint at Rose Danceland (from December 1927). Worked mainly in New York during the late 1920s – several periods of inactivity – but during 1928 and 1929 played various venues including Strand Roof, Roseland, Cotton Club (July 1929), etc. During the early 1930s played the Roseland, Sa voy Ballroom, and toured with the ‘Hot Chocolates’ revue. From late 1931 the band began playing long regular seasons at the Savoy Ballroom (later fronted by Bardu Ali). -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

Ella Fitzgerald Biography Mini-Unit

Page 1 Ella Fitzgerald Biography Mini-Unit A Mini-Unit Study by Look! We’re Learning! ©2014 Look! We’re Learning! ©Look! We’re Learning! Page 2 This printable pack is an original creation from Look! We’re Learning! All rights are reserved. If you would like to share this pack with others, please do so by directing them to the post that features this pack. Please do not redistribute this printable pack via direct links or email. This pack makes use of several online images and includes the appropriate permissions. Special thanks to the following authors for their images: Lewin/Kaufman/Schwartz, Public Relations, Beverly Hills via Wikimedia Commons U.S. Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons William P. Gottlieb Collection via Wikimedia Commons Hans Bernhard via Wikimedia Commons White House Photo Office via Wikimedia Commons ©Look! We’re Learning! Page 3 Ella Fitzgerald Biography Ella Fitzgerald was an American jazz singer who became famous during the 1930s and 1940s. She was born on April 25, 1917, in Newport News, Virginia to William and Temperance Fitzgerald. Shortly after Ella turned three, her mother and father separated and the family moved to Yonkers, New York. When Ella was six, her mother had another little girl named Frances. As a child, Ella loved to sing and, like many jazz and soul musicians, she gained most of her early musical experience at church. When Ella got older, she developed a love for dancing and frequented many of the famous Harlem jazz clubs of the 1920s, including the Savoy Ballroom and the Cotton Club. -

The Impact of the Music of the Harlem Renaissance on Society

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1989 Volume I: American Communities, 1880-1980 The Impact of the Music of the Harlem Renaissance on Society Curriculum Unit 89.01.05 by Kenneth B. Hilliard The community of Harlem is one which is rich in history and culture. Throughout its development it has seen everything from poverty to urban growth. In spite of this the people of this community banded together to establish a strong community that became the model for other black urban areas. As a result of this millions have migrated to this community since the 1880’s, bringing with them heritages and traditions of their own. One of these traditions was that of music, and it was through music that many flocked to Harlem, especially in the 1920’s through 1950’s to seek their fortune in the big apple. Somewhere around the year 1918 this melting pot of southern blacks deeply rooted in the traditions of spirituals and blues mixed with the more educated northern blacks to create an atmosphere of artistic and intellectual growth never before seen or heard in America. Here was the birth of the Harlem Renaissance. The purpose of this unit will be to; a. Define the community of Harlem. b. Explain the growth of music in this area. c. Identify important people who spearheaded this movement. d. Identify places where music grew in Harlem. e. Establish a visual as well as an aural account of the musical history of this era. f. Anthologize the music of this era up to and including today’s urban music. -

Black Dance Stories Presents All-New Episodes Featuring Robert

Black Dance Stories Presents All-New Episodes Featuring Robert Garland & Tendayi Kuumba (Apr 8), Amy Hall Garner & Amaniyea Payne (Apr 15), NIC Kay & Alice Sheppard (Apr 22), Christal Brown & Edisa Weeks (Apr 29) Thursdays at 6pm EST View Tonight’s Episode Live on YouTube at 6pm EST Robert Battle and Angie Pittman Episode Available Now (Brooklyn, NY/ March 8, 2021) – Black Dance Stories will present new episodes in April featuring Black dancers, choreographers, movement artists, and creatives who use their work to raise societal issues and strengthen their community. This month the dance series brings together Robert Garland & Tendayi Kuumba (Apr 8), Amy Hall Garner & Amaniyea Payne (Apr 15), NIC Kay & Alice Sheppard (Apr 22), Christal Brown & Edisa Weeks (Apr 29), and Robert Battle & Angie Pittman (Apr 1). The incomparable Robert Garland (Dance Theatre of Harlem) and renaissance woman Tendayi Kuumba (American Utopia) will be guests on an all-new episode of Black Dance Stories tonight, Thursday, April 8 at 6pm EST. Link here. Robert Battle, artistic director of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and Angie Pittman, Bessie award- winning dancer, joined the Black Dance Stories community on April 1. In the episode, they talk about (and sing) their favorite hymens, growing up in the church, and the importance of being kind. During the episode, Pittman has a full-circle moment when she shared with Battle her memory of meeting him for the first time and being introduced to his work a decade ago. View April 1st episode here. Conceived and co-created by performer, producer, and dance writer Charmaine Warren, the weekly discussion series showcases and initiates conversations with Black creatives that explore social, historical, and personal issues and highlight the African Diaspora's humanity in the mysterious and celebrated dance world. -

Frankie Manning: Ambassador of Lindy Hop Free

FREE FRANKIE MANNING: AMBASSADOR OF LINDY HOP PDF Frankie Manning,Cynthia R. Millman | 312 pages | 28 Sep 2008 | Temple University Press,U.S. | 9781592135646 | English | Philadelphia PA, United States Frankie Manning - Wikipedia N o one has contributed more to the Lindy Hop than Frankie Manning -- as a dancer, innovator and choreographer. For much of his lifetime he was an unofficial Ambassador of Lindy Hop. Once again, since the swing dance revival that started in the s, Frank Manning was a driving force worldwide with his teaching, choreography and performance. His own love of swing music and dancing was contagious as his dazzling smile. History African Roots Reading. F rankie Manning started dancing in his early teens at a Sunday afternoon dance at the Alhambra Ballroom in Harlem to the music of Vernon Andrade. From there he moved on to the Rennaissance Ballroomwhich had an early Frankie Manning: Ambassador of Lindy Hop dance for older teens with the live swing music of the Claude Hopkins Orchestra. Finally, Frankie "graduated" to the Savoy Ballroomwhich was known for its great dancers and bands. Competitive as well as gifted, Manning, became a star in the informal jams in the " Kat's Korner " of Frankie Manning: Ambassador of Lindy Hop Savoy, frequently won the Saturday night contests, and was invited to join the elite Clubwhose members could come to the Savoy Ballroom daytime hours to practise alongside the bands that were booked at the Savoy. F Frankie Manning: Ambassador of Lindy Hop Manning's dancing stood out, even among the greats of the Savoy Ballroom, for its unerring musicality. -

Savoy Ballroom 03-16-03

Roxane Due Professor David Popalisky Final Paper: Savoy Ballroom 03-16-03 Savoy Ballroom: A place where African Americans Shined Many clubs have been named after the famous Savoy Ballroom located at 596 Lenox Avenue, between West 140th Street and West 141st Street, in Harlem, New York. These clubs can be found in Boston, Chicago, California, and many other places. But the Savoy ballroom in Harlem was known as the world's most beautiful, famous ballroom. The Savoy has been called many different things; "The World's Most Beautiful Ballroom", "The Home of Happy Feet," and later as "The Track", but it all comes down to one thing, the Savoy Ballroom was a dancer's paradise. After the Civil War African Americans left the South. The failure of the Reconstruction, the establishment of the Ku Klux Klan, and Jim Crow led to begin the migration to the North. World War I and the stoppage of European Immigrants opened up jobs. The growth of the KKK and the poor cropping grounds gave African Americans even better excuses to continue migration. Many black Americans migrated to northern cities such as Chicago, Washington D.C., and New York City. By 1930 200,000 blacks populated Harlem. "The rise in the African American population coincided with over development of Harlem by white entrepreneurs. In 1907 four hundred and fifty tenements were built in Central Harlem at 135street for white tenants. When whites began to pass Harlem for the Bronx and Washington Heights this area was opened to black renters and buyers." As blacks continued to leave many brought all they had. -

HARLEM RENAISSANCE MAN: JOHNNY HUDGINS Presented in Conjunction with the Uptown Triennial 2020 Exhibition

HARLEM RENAISSANCE MAN: JOHNNY HUDGINS Presented in conjunction with the Uptown Triennial 2020 exhibition. Lecturer: Robert G. O’Meally, Zora Neale Hurston Professor of English and Comparative Literature and Founder and Director of Columbia University’s Jazz Center Moderator: Jennifer Mock, Associate Director for Education and Public Programs, Wallach Art Gallery TRANSCRIPT (BLACK TITLE SLIDE ONSCREEN WITH WHITE TEXT THAT READS “CONTINUITIES OF THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: JOHNNY HUDGINS AND COURTNEY BRYAN COME ON - A TALK BY ROBERT G. O’MEALLY FEATURING MUSIC BY COURTNEY BRYAN” ABOVE THE IMAGE OF ROMARE BEARDEN’S COLLAGE JOHNNY HUDGINS COMES ON) Robert G. O'Meally: I am very grateful to Jennifer (Mock) and to the Wallach Gallery. And I would join her in urging you to see the Uptown Triennial (2020) show. It's right in our neighborhood and you can see part of it online, but you can walk over and take a look as well. I'm very happy to be here, and I'm hoping that we'll have a chance as we meet together this time to have as much fun as anything else. We need some fun out here. As we face another day with the children home from school tomorrow - we're glad to have children home, but quite enough of that some of us would say. And so let's take a break from all of that, and take a look at a performer named Johnny Hudgins. This is a long shot if ever there was one. In talking about the Harlem Renaissance, I bet every single one of the people on the (Zoom) call, could call the role of the Zora Neale Hurstons, and the Alain Lockes, and that you would never get to Johnny Hudgins, most of you. -

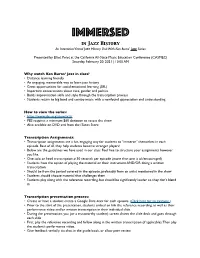

Elliot Polot: Immersed in Jazz History

Immersed in Jazz History An Interactive Virtual Jazz History Unit With Ken Burns' Jazz Series Presented by Elliot Polot at the California All-State Music Education Conference (CASMEC) Saturday, February 20, 2021 | 10:00 AM Why watch Ken Burns’ Jazz in class? • Distance learning friendly • An engaging, memorable way to learn jazz history • Great opportunities for social-emotional learning (SEL) • Important conversations about race, gender, and politics • Builds improvisation skills and style through the transcription process • Students return to big band and combo music with a newfound appreciation and understanding How to view the series: • https://www.pbs.org/show/jazz/ • PBS requires a minimum $60 donation to access the show • Also available on DVD and from the iTunes Store Transcription Assignments: • Transcription assignments are a fun, engaging way for students to “immerse” themselves in each episode. Best of all, they help students become stronger players! • Below are the guidelines we have used in our class. Feel free to structure your assignments however you like. • One solo or head transcription ≥ 30 seconds per episode (more than one is ok/encouraged) • Students have the option of playing the material on their instrument AND/OR doing a written transcription • Should be from the period covered in the episode, preferably from an artist mentioned in the show • Students should choose material that challenges them • Students play along with the reference recording, but should be significantly louder so they don’t blend in Transcription presentation process: • Create or have a student create a Google Slide deck for each episode. (Click here for an example.) • Prior to the start of the presentation, students embed or link the reference recording, as well as their performance video and/or written transcription in their individual slide. -

STARK, 'Bobbie'

THE PRE-CHICK WEBB RECORDINGS OF BOBBY STARK An Annotated Tentative Personnelo - Discography STARK, ‘Bobbie’ Robert Victor, trumpet born:, New York City, 6th January 1906; died: New York City, 29th December 1945 Began on the alto horn at 15, taught by Lt. Eugene Mikell Sr. at M.T. Industrial School, Bordentown, New Jersey, also studied piano and reed instruments before specialising on trumpet. First professional work subbing for June Clark at Small´s (Sugar Cane Club – KBR), New York (late 1925), then played for many bandleaders in New York including: Edgar Dowell, Leon Abbey, Duncan Mayers, Bobby Brown, Bobby Lee, Billy Butler, and Charlie Turner, also worked briefly in McKinney´s Cotton Pickers. Worked with Chick Webb on and off during 1926-7. Joined Fletcher Henderson early in 1928 and remained with that band until late 1933 except for a brief spell with Elmer Snowden in early 1932. With Chick Webb from 1934 until 1939. Free-lancing, then service in U.S. Army from 14th November 1943. With Garvin Bushell´s Band at Tony Pastor´s Club, New York, from April until July 1944, then worked at Camp Unity with Cass Carr until joining Benny Morton´s Sextet at Café Society (Downtown) New York in September 1944. (J. Chilton, Who´s Who Of Jazz) BOBBY E. STARK (trumpet), b. New York, Jan. 6/06. d. New York, Dec 29/45. Played with Chick Webb´s small band (1927); said also to have worked with McKinney´s Cotton Pickers, but this seems unlikely; joined Fletcher Henderson Nov/27, stayed until c Mar/34 (except said to have left briefly to Elmer Snowden, early 1932). -

Aug-Sept 1980

MODERN DRUMMER VOL. 4 NO. 4 FEATURES: KEITH KNUDSEN and CHET MCCRACKEN Keith Knudsen and Chet McCracken, drummers for the pop- ular Doobie Brothers, relate how the advantages outweigh the difficulties working in a two drummer situation. The pair also evaluate their own performance styles and preferences within the musical context of the band. 12 JOE COCUZZO Having worked professionally since the age of 19, Joe Co- cuzzo has an abundance of musical knowledge. His respect for and understanding of the drummer's position within the music has prepared him for affiliations with Buddy DeFranco, Gary McFarland, Don Ellis, Woody Herman and Tony Bennett. 20 ED GREENE Ed Greene has the distinction of being one of Los Angeles' hottest studio drummers. Greene explains what it's like to work in the studios while trying to keep your personal musical goals alive, and what the responsibilities of a studio musician entail. He also speaks on the methods used in a recording studio and how the drums are appropriately adjusted for each session. 29 THE GREAT JAZZ DRUMMERS, INSIDE STAR INSTRUMENTS 26 PART II 16 MORRIS LANG: N.Y. PHILHARMONIC VETERAN 24 COLUMNS: EDITOR'S OVERVIEW 2 SHOW AND STUDIO READERS' PLATFORM 4 Music Cue by Danny Pucillo 46 ASK A PRO 7 UP AND COMING IT'S QUESTIONABLE 8 Rob the Drummer: A New Kid on the Street ROCK PERSPECTIVES by Karen Larcombe 48 A Practical Application of the Five Stroke Roll by David Garibaldi 32 DRUM MARKET 56 STRICTLY TECHNIQUE CLUB SCENE Wrist Versus Fingers Space Saving and the Custom Set by Forrest Clark 34 by Rick Van Horn 60 JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP Coordinating Accents Independently PRINTED PAGE 70 by Ed Soph 38 RUDIMENTAL SYMPOSIUM DRIVER'S SEAT Rudimental Set Drumming Avoiding Common Pitfalls by Ken Mazur 74 by Mel Lewis 42 TEACHER'S FORUM INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS 78 An Overview by Charley Perry 44 JUST DRUMS 79 Two years ago, MD mailed questionaires to 1,000 randomly selected subscribers in an effort to obtain a profile of a typical MD reader.