Film History As Cultural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Personality Development - English 1 Personality Development - English 2 Initiative for Moral and Cultural Training [IMCTF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8831/personality-development-english-1-personality-development-english-2-initiative-for-moral-and-cultural-training-imctf-168831.webp)

Personality Development - English 1 Personality Development - English 2 Initiative for Moral and Cultural Training [IMCTF]

Personality Development - English 1 Personality Development - English 2 Initiative for Moral and Cultural Training [IMCTF] Personality Development (English) Details Book Name : Personality Development (English) Edition : 2015 Pages : 224 Size : Demmy 1/8 Published by : Initiative for Moral and Cultural Training Foundation (IMCTF) Head Office : 4th Floor, Ganesh Towers, 152, Luz Church Road, Mylapore, Chennai - 600 004. Admin Office : 2nd Floor, “Gargi”, New No.6, (Old No.20) Balaiah Avenue, Luz, Mylapore, Chennai - 600 004. Email : [email protected], Website : www.imct.org.in This book is available on Website : www.imct.org.in Printed by : Enthrall Communications Pvt. Ltd., Chennai - 30 © Copy Rights to IMCTF Personality Development - English Index Class 1 1. Oratorical ................................................................................................12 2. Great sayings by Thiruvalluvar .........................................................12 3. Stories .......................................................................................................12 4. Skit ........................................................................................................15 Class 2 1. Oratorical .................................................................................................16 2. Poems .......................................................................................................16 3. Stories .......................................................................................................18 4. -

Unclaimed Dividend

Nature of Date of transfer to Name Address Payment Amount IEPF A B RAHANE 24 SQUADRON AIR FORCE C/O 56 APO Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 A K ASTHANA BRANCH RECRUITING OFFICE COLABA BOMBAY Dividend 37.50 02-OCT-2018 A KRISHNAMOORTHI NO:8,IST FLOOR SECOND STREET,MANDAPAM ROAD KILPAUK MADRAS Dividend 300.00 02-OCT-2018 A MUTHALAGAN NEW NO : 1/194 ELANJAVOOR HIRUDAYAPURAM(P O) THIRUMAYAM(TK) PUDHUKOTTAI Dividend 15.00 02-OCT-2018 A NARASIMHAIAH C/O SRI LAXMI VENKETESWAR MEDICAL AGENCIES RAJAVEEDHI GADWAL Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 A P CHAUDHARY C/O MEHATA INVESTMENT 62, NAVI PETH , NR. MALAZA MARKET M.H JALGAON Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 A PARANDHAMA NAIDU BRANCH MANAGER STATE BANK OF INDIA DIST:CHITTOOR,AP NAGALAPURAM Dividend 112.50 02-OCT-2018 A RAMASUBRAMAIAN NO. 22, DHANLEELA APPT., VALIPIR NAKA, BAIL BAZAR, KALYAN (W), MAHARASHTRA KALYAN Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 A SREENIVASA MOORTHY 3-6-294 HYDERAGUDA HYDERABAD Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 A V NARASIMHARAO C-133 P V TOWNSHIP BANGLAW AREA MANUGURU Dividend 262.50 02-OCT-2018 A VENKI TESWARDKAMATH CANARA BANK 5/A,21, SAHAJANAND PATH MUMBAI Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABBAS TAIYEBALI GOLWALA C/O A T GOLWALA 207 SAIFEE JUBILEE HUSEINI BLDG 3RD FLOOR BOMBAY 40000 BOMBAY Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABDUL KHALIK HARUNRAHID DIST.BHARUCH (GUJ) KANTHARIA Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABDUL SALIM AJ R T C F TERLS VSSC TRIVANDRUM Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABDUL WAHAB 3696 AUSTODIA MOTI VAHOR VAD AHMEDABAD Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABHA ANAND PRAKASHGANDHI DOOR DARSHAN KENDRA POST BOX 5 KOTHI COMPOUND RAJKOT Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABHAY KUMAR DOSHI DHIRENDRA SOTRES MAIN BAZAR JASDAN RAJKOT Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABHAY KUMAR DOSHI DHIRENDRA SOTRES MAIN BAZAR JASDAN RAJKOT Dividend 150.00 02-OCT-2018 ABHINAV KUMAR 5712, GEORGE STREET, APT NO. -

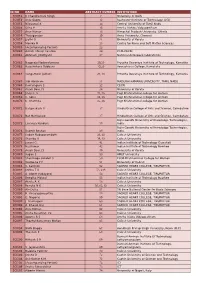

Id No Name Abstract Number

ID NO NAME ABSTRACT NUMBER INSTITUTION SCI051 K Chandramani Singh 7 University of Delhi SCI052 Anju Gupta 12 Rochester Institute of Technology, USA SCI053 Nilavarasi K 14 Central University of Tamil Nadu SCI054 Dilna P 15 Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham SCI055 Arun Kumar 16 Himachal Pradesh University, Shimla SCI056 Thiyagarajan 19 Anna University, Chennai SCI057 Jyothi G 21 University of Kerala SCI058 Monika M 23 Centre for Nano and Soft Matter Sciences SCI059 (Accompanying Person) 23 SCI060 Ashish Shivaji Salunke 24 CSIR-CECRI SCI061 Abhilash J Kottiyatil 27 National Aerospace laboratories SCI062 Nagaraja Nadavalumane 29,30 Proudha Devaraya Institute of Technology, Karnatka SCI063 Rajashekara Gobburu 29,30 Veerashiava College, Karnataka SCI064 Sangamesh Jakhati 29, 30 Proudha Devaraya Institute of Technology, Karnatka SCI065 Sibi Abraham 31 MADURAI KAMARAJ UNIVERSITY, TAMIL NADU SCI066 Kumaraguru S 32 CECRI SCI067 Anjali Devi J S 34 University of Kerala SCI068 Jincy C. S. 35, 36 Psgr Krishnammal college for women SCI069 C. Selvi 35, 36 Psgr Krishnammal college for women SCI070 C. Sharmila 35, 36 Psgr Krishnammal college for women SCI071 Balaprakash V 37 Hindusthan College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore SCI072 Not Mentioned 37 Hindusthan College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Rajiv Gandhi University of Knowledge Technologies, SCI073 Lavanya Kunduru 38 India Rajiv Gandhi University of Knowledge Technologies, SCI074 Rakesh Roshan 38 India SCI075 Subair Naduparambath 39, 40 Calicut University SCI076 Shaniba V 39, 40 Calicut University SCI077 Janani G. 41 Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati SCI078 Raj Kumar 42 Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee SCI079 Anjali Devi J S 49 University of Kerala SCI080 Sugan S 50 AMET University SCI081 Shanmuga Sundari S 50 PSGR Krishnammal College for Women SCI082 Soufeena P P 51 University of Calicut SCI083 S. -

2012 - March 2013

1 2 One force shall be your mover and your guide, One light shall be around you and within; Hand in strong hand confront Heaven’s question, life: Challenge the ordeal of the immense disguise. Ascend from Nature to divinity’s heights; Face the high gods, crowned with felicity, Then meet a greater god, thy self beyond Time.” This word was seed of all the thing to be: A hand from some Greatness opened her heart’s locked doors And showed the work for which her strength was born. - “Savitri” by Sri Aurobindo - Book IV, Canto III 1 3 CONTENTS ACTIVITY REPORT APRIL 2012 - MARCH 2013 Highlights 1 Patient Care 7 Education and Training 21 Consultancy and Capacity Building 39 Research 49 Ophthalmic Supplies 57 Central Functions 61 Awards and Accolades 66 Partners in Service 70 Trustees and Staff 72 Photo Credits Mohan, Aravind–Tirunelveli Mike Myers, USA Iruthayaraj, Aravind–Pondicherry Rajkumar, Aravind–Madurai Sasipriya, LAICO–Madurai Senthil Kumar, Aravind–Coimbatore 2 4 6$373Y9R[3J[ All across South India every morning in front of each home, patterns are drawn on the ground with steady streams of white powder (traditionally made from rice flour) released between thumb and forefinger, weaving in continuous curving lines around a pattern of small dots.They are called Kolams and their variations are infinite and fascinating…in many ways they remind us of the beautiful patterns that emerge in our lives merely by connecting-the-dots….for in a finished kolam not a single dot is left un-embraced. Aravind has become a pattern-unto-itself and the ideas, inspirations and individuals who weave in and out of its work for sight continue to create powerful connections. -

The Journal of International Communication Film Remakes As

This article was downloaded by: [Mr C.S.H.N. Murthy] On: 08 January 2015, At: 09:46 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Journal of International Communication Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rico20 Film remakes as cross-cultural connections between North and South: A case study of the Telugu film industry's contribution to Indian filmmaking C.S.H.N. Murthy Published online: 13 Nov 2012. To cite this article: C.S.H.N. Murthy (2013) Film remakes as cross-cultural connections between North and South: A case study of the Telugu film industry's contribution to Indian filmmaking, The Journal of International Communication, 19:1, 19-42, DOI: 10.1080/13216597.2012.739573 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13216597.2012.739573 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Smita Patil: Fiercely Feminine

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 Smita Patil: Fiercely Feminine Lakshmi Ramanathan The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2227 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SMITA PATIL: FIERCELY FEMININE BY LAKSHMI RAMANATHAN A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 i © 2017 LAKSHMI RAMANATHAN All Rights Reserved ii SMITA PATIL: FIERCELY FEMININE by Lakshmi Ramanathan This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts. _________________ ____________________________ Date Giancarlo Lombardi Thesis Advisor __________________ _____________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Acting Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT SMITA PATIL: FIERCELY FEMININE by Lakshmi Ramanathan Advisor: Giancarlo Lombardi Smita Patil is an Indian actress who worked in films for a twelve year period between 1974 and 1986, during which time she established herself as one of the powerhouses of the Parallel Cinema movement in the country. She was discovered by none other than Shyam Benegal, a pioneering film-maker himself. She started with a supporting role in Nishant, and never looked back, growing into her own from one remarkable performance to the next. -

We Had Vide HO Circular 443/2015 Dated 07.09.2015 Communicated

1 CIRCULAR NO.: 513/2015 HUMAN RESOURCES WING I N D E X : STF : 23 INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS SECTION HEAD OFFICE : BANGALORE-560 002 D A T E : 21.10.2015 A H O N SUB: IBA MEDICAL INSURANCE SCHEME FOR RETIRED OFFICERS/ EMPLOYEES. ******* We had vide HO Circular 443/2015 dated 07.09.2015 communicated the salient features of IBA Medical Insurance Scheme for the Retired Officers/ Employees and called for the option from the eligible retirees. Further, the last date for submission of options was extended upto 20.10.2015 vide HO Circular 471/2015 dated 01.10.2015. The option received from the eligible retired employees with mode of exit as Superannuation, VRS, SVRS, at various HRM Sections of Circles have been consolidated and published in the Annexure. We request the eligible retired officers/ employees to check for their name if they have submitted the option in the list appended. In case their name is missing we request such retirees to take up with us by 26.10.2015 by sending a scan copy of such application to the following email ID : [email protected] Further, they can contact us on 080 22116923 for further information. We also observe that many retirees have not provided their email, mobile number. In this regard we request that since, the Insurance Company may require the contact details for future communication with the retirees, the said details have to be provided. In case the retirees are not having personal mobile number or email ID, they have to at least provide the mobile number or email IDs of their near relatives through whom they can receive the message/ communication. -

![ENGLISH, Paper – II (Third Language) Parts a and B Time: 2 ½ Hours] [Maximum Marks: 50](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1817/english-paper-ii-third-language-parts-a-and-b-time-2-%C2%BD-hours-maximum-marks-50-1691817.webp)

ENGLISH, Paper – II (Third Language) Parts a and B Time: 2 ½ Hours] [Maximum Marks: 50

This Question Paper contains 2 Printed Pages. ENGLISH, Paper – II (Third language) Parts A and B Time: 2 ½ Hours] [Maximum Marks: 50 Instructions: 1. Answer the questions under Part-A on a separate answer book. 2. Write the answers to the questions under Part-B on the question paper itself in the space provided and attach it to the answer book of Part-A. 3. Start answering the questions as you read them. Part - A Time: 1 ½ Hours Marks: 30 (1-10) Answer ANY FIVE of the following questions. Each answer should be in one or two sentences. 5x1=5 1. What ‘in Narayana Murthy’s opinion’ can change one’s life? (I’ll do it) 2. What things would you buy if you were Jack? Why? (The Never-Never Nest) 3. The King made the Potter the General of the Army? Why? (The brave Potter) 4. What made the Potter a hero? (The brave Potter) 5. Narayana Murthy is uncompromising. How? 6. Why are Savitri’s films called ‘an album of life’? (A Tribute) 7. How was the abandoned baby? (Abandoned) 8. What are the evil effects of pyramid of drums? (A tale of three villages) 9. What made superficial observers bewildered about India? (Unity in diversity in India) 10. What made Mrs. Murthy forget her name? (What is my name) 11. Read the following passage. 5x1=5 Savitri captured the audiences with her charm and magnificent acting. She was able to convey a wide range of feelings through her expressive eyes. Her mischievous look- it captivates anyone; the look of fake anger provokes, the looks filled with real anger pierces the heart. -

Unclaimed Dividend 2011-12 As on 31.12.2018

NCL INDUSTRIES LTD Dividend A/c No - 0133103000006798 LIST OF UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND AS ON 31/12/2018 FOR THE FY 2011-12 S.No. FOLIO MICR AMOUNT WARDATE NAME WARNO 1 000004 14753 200 01-10-2012 S VISWANATHA RAJU 90 2 000008 13861 20 01-10-2012 G.VENKATA DURGA RAJU 124 3 000025 13862 400 01-10-2012 G VISHWANADHA RAJU 263 4 000028 13863 80 01-10-2012 K SAVITRI 279 5 000053 17525 800 01-10-2012 B BHAGAVATHI RAO 411 6 000054 17524 500 01-10-2012 KADA SRINIVASA RAO 415 7 000056 17503 200 01-10-2012 PENTA ANANDA RAO 425 8 000057 17504 480 01-10-2012 PENTA MANMADA RAO 428 9 000058 17505 400 01-10-2012 PENTA VENKATA RAJU 434 10 000059 17446 500 01-10-2012 CHITTORI VENKATA KRISHNA NARASIMHA RAO439 11 000061 17506 200 01-10-2012 PENTA KRISHNA RAO 455 12 000062 17507 200 01-10-2012 PENTA SURYA RAO 464 13 000063 17508 200 01-10-2012 PENTA KAMESHWARA RAO 468 14 000064 17509 200 01-10-2012 PENTA BALARAMA MURTHY 471 15 000067 17864 240 01-10-2012 BONDA NOOKA RAJU 487 16 000070 17865 200 01-10-2012 MAMIDI VARAHA NARASIMHA MURTHY 504 17 000073 17866 600 01-10-2012 PALURI VENKATA RAMANA 520 18 000075 15536 100 01-10-2012 CH CHANDRA REDDY 530 19 000078 17268 60 01-10-2012 RAVI NAGHABUSHANAM 550 20 000105 13864 1300 01-10-2012 G.SUBBAYAMMA 674 21 000107 13612 30 01-10-2012 RAMESH ARORA 684 22 000133 19937 120 01-10-2012 M VARALAXMI 790 23 000134 14568 120 01-10-2012 K SARADAMBA 794 24 000135 972 120 01-10-2012 T MANIKYAMBA 799 25 000137 973 120 01-10-2012 U SUSHEELA 804 26 000138 13918 120 01-10-2012 K RAJYALAXMI 809 27 000161 12743 500 01-10-2012 RAVI PEDA -

Annexure 1B 18416

Annexure 1 B List of taxpayers allotted to State having turnover of more than or equal to 1.5 Crore Sl.No Taxpayers Name GSTIN 1 BROTHERS OF ST.GABRIEL EDUCATION SOCIETY 36AAAAB0175C1ZE 2 BALAJI BEEDI PRODUCERS PRODUCTIVE INDUSTRIAL COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED 36AAAAB7475M1ZC 3 CENTRAL POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE 36AAAAC0268P1ZK 4 CO OPERATIVE ELECTRIC SUPPLY SOCIETY LTD 36AAAAC0346G1Z8 5 CENTRE FOR MATERIALS FOR ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY 36AAAAC0801E1ZK 6 CYBER SPAZIO OWNERS WELFARE ASSOCIATION 36AAAAC5706G1Z2 7 DHANALAXMI DHANYA VITHANA RAITHU PARASPARA SAHAKARA PARIMITHA SANGHAM 36AAAAD2220N1ZZ 8 DSRB ASSOCIATES 36AAAAD7272Q1Z7 9 D S R EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY 36AAAAD7497D1ZN 10 DIRECTOR SAINIK WELFARE 36AAAAD9115E1Z2 11 GIRIJAN PRIMARY COOPE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED ADILABAD 36AAAAG4299E1ZO 12 GIRIJAN PRIMARY CO OP MARKETING SOCIETY LTD UTNOOR 36AAAAG4426D1Z5 13 GIRIJANA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED VENKATAPURAM 36AAAAG5461E1ZY 14 GANGA HITECH CITY 2 SOCIETY 36AAAAG6290R1Z2 15 GSK - VISHWA (JV) 36AAAAG8669E1ZI 16 HASSAN CO OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UNION LTD 36AAAAH0229B1ZF 17 HCC SEW MEIL JOINT VENTURE 36AAAAH3286Q1Z5 18 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISER COOPERATIVE LIMITED 36AAAAI0050M1ZW 19 INDU FORTUNE FIELDS GARDENIA APARTMENT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 36AAAAI4338L1ZJ 20 INDUR INTIDEEPAM MUTUAL AIDED CO-OP THRIFT/CREDIT SOC FEDERATION LIMITED 36AAAAI5080P1ZA 21 INSURANCE INFORMATION BUREAU OF INDIA 36AAAAI6771M1Z8 22 INSTITUTE OF DEFENCE SCIENTISTS AND TECHNOLOGISTS 36AAAAI7233A1Z6 23 KARNATAKA CO-OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCER\S FEDERATION -

(S/SRI/SMT/Ms) FATHER NAME

SLNO NAME (S/SRI/SMT/Ms) FATHER NAME (S/SRI) DESIGNATION BILLUNIT DEPARTMENT PFNO 1 D.N.MANORAMA D.J.MANOHAR AA 00000 ACCOUNTS 01114700 2 P SHANKAR STYPST 00000 ACCOUNTS 03102063 3 B.SARADA PADMINI K.RAMA KRISHNA SR.SEC.OFFR A/C 00000 ACCOUNTS 10001700 4 G. NAGESWARA RAO SR.SEC.OFFR A/C 00000 ACCOUNTS 03673534 5 S. RAMA SASTRY CTYPST 00000 ACCOUNTS 10052008 6 M R VIJAYABHASKAR JAYA RAO AA 00000 ACCOUNTS 08045550 7 A.RAMA RAJU VENKATA RAJU ACLRK 00000 ACCOUNTS 03167719 8 M RANGA CHARYULU STGPR1 00000 ACCOUNTS 01117099 9 S KARUNAKARAN SR.SEC.OFFR A/C 00000 ACCOUNTS 07103384 10 S.SATYANARAYANA S VITTALL RAO CTYPST 00000 ACCOUNTS 04521237 11 T.SUDHAKAR T.AGAIAH MVDRVR 00000 ACCOUNTS IZ060386 12 L.SANTOSH KUMAR L.SATYANARAYANA PEON 00000 ACCOUNTS IA080079 13 K.P.PRANAY KUMAR K.N. PRAMOD KUMAR JAA 00000 ACCOUNTS IZ040001 14 M SAVITRI M PANDURANGA ACLRK 00000 ACCOUNTS IA090043 15 RAJEEV BAGALWADI SR.SEC.OFFR A/C 00000 ACCOUNTS 07103232 16 MANSOOR HUSSAIN .C SR.SEC.OFFR A/C 00000 ACCOUNTS 05484716 17 G HANUMANTHA RAO SR.SEC.OFFR A/C 00000 ACCOUNTS 03099106 18 CH N V L SUNDARA RAO CH V RAMANA RAO SR.SEC.OFFR A/C 00000 ACCOUNTS 01120098 19 L SATHYANARAYANA L NARASIMHA AA 00000 ACCOUNTS 01112168 20 MOHD SALEEM MOHD KASIM MVDRVR 00000 ACCOUNTS 01112235 21 MOHD OSMAN MOHD KASIM MVDRVR 00000 ACCOUNTS 01112247 22 MAHESH KUMAR D MALLIAH D AA 00000 ACCOUNTS 01112259 23 B VINAY KUMAR B ASEERVADAM SR.SEC.OFFR A/C 00000 ACCOUNTS 01121595 24 KUMAR K B M NAGALINGA SARMA HDTYST 00000 ACCOUNTS 01121674 25 K.RAGHUNATH STYPST 00000 ACCOUNTS 01110068 26 NARENDER -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons For

Form9_AC153_24/11/2020 http://eronet.ecinet.in/FormProcess/GetFormReport ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Neyveli Revision identy applicaons have been received) From date To date 1. List number@ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 22/11/2020 22/11/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial number$ Date of Name of Father / Mother / Da Name of claimant Place of residence of receipt Husband and (Relaonship)# hea applicaon 1 22/11/2020 S Manikandan G Subramanian (F) 106/1F, Middle street, Tenkuthu, , Cuddalore 2 22/11/2020 Srikanth Chitra V (M) 111/2, East Street, Muthukrishnapuram, , Cuddalore No 348, Sri Sakthi Nagar 3 22/11/2020 Aldrin Antony AAlbert Kumar A (F) Extension, Vadakuthu, , Cuddalore GOWTHAM 122, ANNA GRAMAM 4 22/11/2020 BALAMURUGAN (F) GANESH EXTENSION, VADAKUTHU, , Cuddalore Mehrunnisa shahirshah mohammed 5 22/11/2020 D‐24, high school road, Neyveli township, , Cuddalore begam Noortheen yakub (H) Shahirshah Mohammed D‐24, high school road Block‐10, Neyveli 6 22/11/2020 Irfana Shahirshah yakub (F) Township, , Cuddalore VIGNESHKUMAR 102, MARIYAMMAN KOVIL 7 22/11/2020 ARUMUGAM (F) ARUMUGAM STREET, ELANTHAMPATTU, , Cuddalore ANITHKUMAR 102, MARIYAMMAN KOVIL 8 22/11/2020 ARUMUGAM (F) ARUMUGAM STREET, ELANTHAMPATTU, , Cuddalore 9 22/11/2020 Meenakshi R Raja Wife Husband (H) B‐28, Bench Street, Block ‐3, Kurinjipadi, , Cuddalore 10 22/11/2020 Vasanth sakthivel (F) 72, North street, vasanankuppam, , Cuddalore