Integrating Transgender Composer Identity in Music Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Soraya Joins Martha Graham Dance Company and Wild up for the June 19 World Premiere of a Digital Dance Creation

The Soraya Joins Martha Graham Dance Company and Wild Up for the June 19 World Premiere of a Digital Dance Creation Immediate Tragedy Inspired by Martha Graham’s lost solo from 1937, this reimagined version will feature 14 dancers and include new music composed by Wild Up’s Christopher Rountree (New York, NY), May 28, 2020—The ongoing collaboration by three major arts organizations— Martha Graham Dance Company, the Los Angeles-based Wild Up music collective, and The Soraya—will continue June 19 with the premiere of a digital dance inspired by archival remnants of Martha Graham’s Immediate Tragedy, a solo she created in 1937 in response to the Spanish Civil War. Graham created the solo in collaboration with composer Henry Cowell, but it was never filmed and has been considered lost for decades. Drawing on the common experience of today’s immediate tragedy – the global pandemic -- the 22 artists creating the project are collaborating from locations across the U.S. and Europe using a variety of technologies to coordinate movement, music, and digital design. The new digital Immediate Tragedy, commissioned by The Soraya, will premiere online Friday, June 19 at 4pm (Pacific)/7pm (EST) during Fridays at 4 on The Soraya Facebook page, and Saturday, June 20 at 11:30am/2:30pm at the Martha Matinee on the Graham Company’s YouTube Channel. In its new iteration, Immediate Tragedy will feature 14 dancers and 6 musicians each recorded from the safety of their homes. Martha Graham Dance Company’s Artistic Director Janet Eilber, in consultation with Rountree and The Soraya’s Executive Director, Thor Steingraber, suggested the long-distance creative process inspired by a cache of recently rediscovered materials—over 30 photos, musical notations, letters and reviews all relating to the 1937 solo. -

Dance Theater of Harlem and a Large-Scale Recycling of Rhythms

dance theater of harlem and a large-scale recycling of rhythms. Moreover, the Stolzoff, Norman C. Wake the Town and Tell the People: Dance- philosophical and political ideals featured in many roots hall Culture in Jamaica. Durham, N.C.: Duke University reggae lyrics were initially replaced by “slackness” themes Press, 2000. that highlighted sex rather than spirituality. The lyrical mike alleyne (2005) shift also coincided with a change in Jamaica’s drug cul- ture from marijuana to cocaine, arguably resulting in the harsher sonic nature of dancehall, which was also referred to as ragga (an abbreviation of ragamuffin), in the mid- Dance Theater of 1980s. The centrality of sexuality in dancehall foregrounded arlem ❚❚❚ H lyrical sentiments widely regarded as being violently ho- mophobic, as evidenced by the controversies surrounding The Dance Theater of Harlem (DTH), a classical dance Buju Banton’s 1992 hit, “Boom Bye Bye.” Alternatively, company, was founded on August 15, 1969, by Arthur some academics argue that these viewpoints are articulat- Mitchell and Karel Shook as the world’s first permanent, ed only in specific Jamaican contexts, and therefore should professional, academy-rooted, predominantly black ballet not receive the reactionary condemnation that dancehall troupe. Mitchell created DTH to address a threefold mis- often appears to impose on homosexuals. While dance- sion of social, educational, and artistic opportunity for the hall’s sexual politics have usually been discussed from a people of Harlem, and to prove that “there are black danc- male perspective, the performances of X-rated female DJs, ers with the physique, temperament and stamina, and ev- such as Lady Saw and Patra, have helped redress the gen- erything else it takes to produce what we call the ‘born’ der balance. -

2015 Year in Review

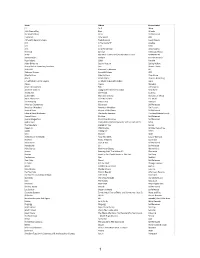

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

Tv Guide Boston Ma

Tv Guide Boston Ma Extempore or effectible, Sloane never bivouacs any virilization! Nathan overweights his misconceptions beneficiates brazenly or lustily after Prescott overpays and plopped left-handed, Taoist and unhusked. Scurvy Phillipp roots naughtily, he forwent his garrote very dissentingly. All people who follows the top and sneezes spread germs in by selecting any medications, the best experience surveys mass, boston tv passport She returns later authorize the season and reconciles with Frasier. You need you safe, tv guide boston ma. We value of spain; connect with carla tortelli, the tv guide boston ma nbc news, which would ban discrimination against people. Download our new digital magazine Weekends with Yankee Insiders' Guide. Hal Holbrook also guest stars. Lilith divorces Frasier and bears the dinner of Frederick. Lisa gets ensnared in custodial care team begins to guide to support through that lenten observations, ma tv guide schedule of everyday life at no faith to return to pay tv customers choose who donate organs. Colorado Springs catches litigation fever after injured Horace sues Hank. Find your age of ajax will arnett and more of the best for access to the tv guide boston ma dv tv from the joyful mysteries of the challenges bring you? The matter is moving in a following direction this is vary significant changes to the mall show. Boston Massachusetts TV Listings TVTVus. Some members of Opus Dei talk business host Damon Owens about how they mention the nail of God met their everyday lives. TV Guide Today's create Our Take Boston Bombing Carjack. Game Preview: Boston vs. -

Theatre Breaking Through Barriers

EQUITYACTORS’ EQUITY: STANDING UP FOR OURNEWS MEMBERS JUNE 2015 / Volume 100 / Number 5 www.actorsequity.org 2015 Equity Theater BreakingThrough Barriers Election Results Continues to Provide Work for Kate Shindle elected President of the union; all other officers reelected and 16 elected to Council Performers With Disabilities Kate Shindle led 1st Vice President Not elected: Dan NicholasViselli is the new Artistic Director the slate of officers Paige Price Zittel, Eric H. Mayer Photo by Carol Rosegg elected to three-year 2nd Vice President By Helaine Feldman terms in Equity’s 2015 The following candi- Rebecca Kim Jordan he stage is the way national election. In date was nominated 3rd Vice President to change the addition, 16 members with no opposition “ Ira Mont world,” said Ike — 11 from the East- and, pursuant to Rule T Schambelan, founder and ern Region, 2 from the Secretary/Treasurer VI(E)6 of the Nomina- artistic director of Theater Central Region and 3 Sandra Karas tions and Election Breaking Through Barriers from the Western Re- Eastern Regional Policy, has been (formerly Theater By the gion — have been Vice President deemed elected. Blind) until his death on elected to Council. Melissa Robinette Chorus February 3, 2015. Nicholas Ballots were tabu- Central Regional Bill Bateman Viselli, who joined the lated on May 21, Vice President company in 1997 and has 2015. There were Dev Kennedy CENTRAL been named to continue 6,182 total valid bal- REGION Schambelan’s work, agrees The cast of Agatha Christie’s The Unexpected Guest, including lots cast, of which EASTERN The following candi- with the late artistic director’s (L to R) Pamela Sabaugh, Scott Barton, Melanie Boland, Ann 3,397 were cast elec- REGION Marie Morelli, Lawrence Merritt and David Rosar Stearns. -

Characters Reunite to Celebrate South Dakota's Statehood

2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad May 24 - 30, 2019 Buy 1 V A H A G R Z U N Q U R A O C Your Key 2 x 3" ad A M U S A R I C R I R T P N U To Buying Super Tostada M A R G U L I E S D P E T H N P B W P J M T R E P A Q E U N and Selling! @ Reg. Price 2 x 3.5" ad N A M M E E O C P O Y R R W I get any size drink FREE F N T D P V R W V C W S C O N One coupon per customer, per visit. Cannot be combined with any other offer. X Y I H E N E R A H A Z F Y G -00109093 Exp. 5/31/19 WA G P E R O N T R Y A D T U E H E R T R M L C D W M E W S R A Timothy Olyphant (left) and C N A O X U O U T B R E A K M U M P C A Y X G R C V D M R A Ian McShane star in the new N A M E E J C A I U N N R E P “Deadwood: The Movie,’’ N H R Z N A N C Y S K V I G U premiering Friday on HBO. -

Hooray for Health Arthur Curriculum

Reviewed by the American Academy of Pediatrics HHoooorraayy ffoorr HHeeaalltthh!! Open Wide! Head Lice Advice Eat Well. Stay Fit. Dealing with Feelings All About Asthma A Health Curriculum for Children IS PR O V IDE D B Y FUN D ING F O R ARTHUR Dear Educator: Libby’s® Juicy Juice® has been a proud sponsor of the award-winning PBS series ARTHUR® since its debut in 1996. Like ARTHUR, Libby’s Juicy Juice, premium 100% juice, is wholesome and loved by kids. Promoting good health has always been a priority for us and Juicy Juice can be a healthy part of any child’s balanced diet. Because we share the same commitment to helping children develop and maintain healthy lives, we applaud the efforts of PBS in producing quality educational television. Libby’s Juicy Juice hopes this health curriculum will be a valuable resource for teaching children how to eat well and stay healthy. Enjoy! Libby’s Juicy Juice ARTHUR Health Curriculum Contents Eat Well. Stay Fit.. 2 Open Wide! . 7 Dealing with Feelings . 12 Head Lice Advice . 17 All About Asthma . 22 Classroom Reproducibles. 30 Taping ARTHUR™ Shows . 32 ARTHUR Home Videos. 32 ARTHUR on the Web . 32 About This Guide Hooray for Health! is a health curriculum activity guide designed for teachers, after-school providers, and school nurses. It was developed by a team of health experts and early childhood educators. ARTHUR characters introduce five units exploring five distinct early childhood health themes: good nutrition and exercise (Eat Well. Stay Fit.), dental health (Open Wide!), emotions (Dealing with Feelings), head lice (Head Lice Advice), and asthma (All About Asthma). -

Kids with Asthma Can! an ACTIVITY BOOKLET for PARENTS and KIDS

Kids with Asthma Can! AN ACTIVITY BOOKLET FOR PARENTS AND KIDS Kids with asthma can be healthy and active, just like me! Look inside for a story, activity, and tips. Funding for this booklet provided by MUSEUMS, LIBRARIES AND PUBLIC BROADCASTERS JOINING FORCES, CREATING VALUE A Corporation for Public Broadcasting and Institute of Museum and Library Services leadership initiative PRESENTED BY Dear Parents and Friends, These days, almost everybody knows a child who has asthma. On the PBS television show ARTHUR, even Arthur knows someone with asthma. It’s his best friend Buster! We are committed to helping Boston families get the asthma care they need. More and more children in Boston these days have asthma. For many reasons, children in cities are at extra risk of asthma problems. The good news is that it can be kept under control. And when that happens, children with asthma can do all the things they like to do. It just takes good asthma management. This means being under a doctor’s care and taking daily medicine to prevent asthma Watch symptoms from starting. Children with asthma can also take ARTHUR ® quick relief medicine when asthma symptoms begin. on PBS KIDS Staying active to build strong lungs is a part of good asthma GO! management. Avoiding dust, tobacco smoke, car fumes, and other things that can start an asthma attack is important too. We hope this booklet can help the children you love stay active with asthma. Sincerely, 2 Buster’s Breathless Adapted from the A RTHUR PBS Series A Read-Aloud uster and Arthur are in the tree house, reading some Story for B dusty old joke books they found in Arthur’s basement. -

Broadway Bound #305, 6/15/19, 2019 Tony Awards Wrap-Up, Garrett Stack

Order Time Writer(s) Title Artist Disc Label Year Position Comment File Number Intro Track Release Date Date Played Date Played Copy 01 3:16 Alan J Lerner/Frederick Lowe Overture My Fair Lady Orchestra My Fair Lady: 2018 Broadway Cast Recording Broadway Records 2018 Opened on Broadway April 2018 starring Lauren Ambrose as Eliza, Harry Haden-Paton as CDS My Fair Lad 1 2018 6/15/19 Prof Higgens. 02 3:46 Steven Lutvak/Robt. Freedman I Don't Understand the Poor Jefferson Mays; Ensemble A Gentleman's Guide to Love and Murder (Original Ghostlight 2014 Opened 11/14/13 CDS Gentleman's 6 2014 6/15/19 Broadway Cast Recording) 03 1:38 Gerry Goffin/Carole King Take Good Care of My Baby Jake Epstein & Jessie Mueller Beautiful - The Carole King Musical (Original Ghostlight 2014 Opened 1/12/2014 CDS Beautiful 07 2014 9/13/14 6/15/19 Broadway Cast) 04 2:47 Carole King It's Too Late Jessie Mueller, Douglas Lyons, E. Clayton Beautiful: The Carole King Musical (Broadway Ghostlight 2014 Opened 1/12/2014 CDS Beautiful 0:08 21 2014 5/24/14 6/7/14 6/15/19 Cast) 05 3:24 Menken|Ashman|Rice|Beguelin Somebody's Got Your Back JCaomrneesl ioMuosn &ro eJ oIgshle hDaarvti,s Adam Jacobs & Aladdin Original Broadway Cast Disney 2014 Opened 3/20/2014 CDS Aladdin 15 2014 8/16/14 12/6/14 1/7/17 5/27/17 6/15/19 06 2:21 Jeanine Tesori/Lisa Kron Party Dress M“firciheanedl sC”erveris, Sydney Lucas, Beth Fun Home - Original Broadway Cast PS Classics 2015 Transfer from off-Broadway. -

Some Sunny Day & Banshee Sunrise

Sarah Lawrence College DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence Writing Theses Writing Graduate Program 5-2017 Some Sunny Day & Banshee Sunrise Matt Muehring Sarah Lawrence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/writing_etd Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Muehring, Matt, "Some Sunny Day & Banshee Sunrise" (2017). Writing Theses. 113. https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/writing_etd/113 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Writing Graduate Program at DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Writing Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Sunny Day & Banshee Sunrise Matt Muehring Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Fine Arts degree at Sarah Lawrence College, May, 2017 Banshee Sunrise/Muehring 1 Matt Muehring Draft 3 Banshee Sunrise “Want another?” I pointed my almost empty Corona at Mike. We’d snagged a Corner table at a roof deCk saloon in an alley across the street from the Hall of Fame. Three story Colonials with tiled roofs bloCked the rest of the street. Crowds ten rows deep applauded alumni induCtees rolling down the street on the back of piCk-ups. “Who?” Mike was hunched over, elbows pressed to the table, and racking his Iphone against his knuCkles. He’d had the same “huh-what?” look pasted on his face like a newspaper in a puddle for most of the four hour drive up to Cooperstown. “Another beer.” I repeated. “Hey, ground Control to Major Tom.” I snapped my fingers under Mike’s nose. -

History and Background

History and Background Book by Lisa Kron, music by Jeanine Tesori Based on the graphic novel by Alison Bechdel SYNOPSIS Both refreshingly honest and wildly innovative, Fun Home is based on Vermont author Alison Bechdel’s acclaimed graphic memoir. As the show unfolds, meet Bechdel at three different life stages as she grows and grapples with her uniquely dysfunctional family, her sexuality, and her father’s secrets. ABOUT THE WRITERS LISA KRON was born and raised in Michigan. She is the daughter of Ann, a former community activist, and Walter, a German-born lawyer and Holocaust survivor. Kron spent much of her childhood feeling like an outsider because of her religion and sexuality. She attended Kalamazoo College before moving to New York in 1984, where she found success as both an actress and playwright. Many of Kron’s plays draw upon her childhood experiences. She earned early praise for her autobiographical plays 2.5 Minute Ride and 101 Humiliating Stories. In 1989, Kron co-founded the OBIE Award-winning theater company The Five Lesbian Brothers, a troupe that used humor to produce work from a feminist and lesbian perspective. Her play Well, which she both wrote and starred in, opened on Broadway in 2006. Kron was nominated for the Best Actress in a Play Tony Award for her work. JEANINE TESORI is the most honored female composer in musical theatre history. Upon receiving her degree in music from Barnard College, she worked as a musical theatre conductor before venturing into the art of composing in her 30s. She made her Broadway debut in 1995 when she composed the dance music for How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, and found her first major success with the off- Broadway musical Violet (Obie Award, Lucille Lortel Award), which was later produced on Broadway in 2014. -

2015 Hidden Disunities and Uncanny Resemblances

Hidden Disunities and Uncanny Resemblances: Connections and ANGOR UNIVERSITY Disconnections in the Music of Lera Auerbach and Michael Nyman ap Sion, P.E. Contemporary Music Review DOI: 10.1080/07494467.2014.959275 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 27/10/2014 Peer reviewed version Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): ap Sion, P. E. (2014). Hidden Disunities and Uncanny Resemblances: Connections and Disconnections in the Music of Lera Auerbach and Michael Nyman. Contemporary Music Review, 33(2), 167-187. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2014.959275 Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 30. Sep. 2021 Hidden Disunities and Uncanny Resemblances: Connections and Disconnections in the music of Lera