Something 'Wyrd' This Way Comes: Folklore and British Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

The 400Th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and Its Meaning in 2012

The 400th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and its Meaning in 2012. Todd Andrew Bridges A thesis submitted for the degree of M.A.D. History 2016. Department of History The University of Essex 27 June 2016 1 Contents Abbreviations p. 3 Acknowledgements p. 4 Introduction: p. 5 Commemorating witch-trials: Lancashire 2012 Chapter One: p. 16 The 1612 Witch trials and the Potts Pamphlet Chapter Two: p. 31 Commemoration of the Lancashire witch-trials before 2012 Chapter Three: p. 56 Planning the events of 2012: key organisations and people Chapter Four: p. 81 Analysing the events of 2012 Conclusion: p. 140 Was 2012 a success? The Lancashire Witches: p. 150 Maps: p. 153 Primary Sources: p. 155 Bibliography: p. 159 2 Abbreviations GC Green Close Studios LCC Lancashire County Council LW 400 Lancashire Witches 400 Programme LW Walk Lancashire Witches Walk to Lancaster PBC Pendle Borough Council PST Pendle Sculpture Trail RPC Roughlee Parish Council 3 Acknowledgement Dr Alison Rowlands was my supervisor while completing my Masters by Dissertation for History and I am honoured to have such a dedicated person supervising me throughout my course of study. I gratefully acknowledge Dr Rowlands for her assistance, advice, and support in all matters of research and interpretation. Dr Rowland’s enthusiasm for her subject is extremely motivating and I am thankful to have such an encouraging person for a supervisor. I should also like to thank Lisa Willis for her kind support and guidance throughout my degree, and I appreciate her providing me with the materials that were needed in order to progress with my research and for realising how important this research project was for me. -

Seeing the Supernatural

SEEING THE SUPERNATURAL How to Sense, Discern and Battle in the Spiritual Realm JENNIFER EIVAZ G Jennifer Eivaz, Seeing the Supernatural Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2017. Used by permission. (Unpublished manuscript—copyright protected Baker Publishing Group) © 2017 by Jennifer Eivaz Published by Chosen Books 11400 Hampshire Avenue South Bloomington, Minnesota 55438 www.chosenbooks.com Chosen Books is a division of Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, Michigan Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, pho- tocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Control Number: 2017941812 ISBN 978-0-8007-9854-3 Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from the Holy Bible, New Inter- national Version®. NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.zondervan.com Scripture quotations identified amp are from the Amplified® Bible, copyright © 2015 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. (www.Lockman.org) Scripture quotations identified esv are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Ver- sion® (ESV®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. ESV Text Edition: 2011 Scripture quotations identified mounce are from THE MOUNCE REVERSE-INTER- LINEAR NEW TESTAMENT Copyright © 2011 by Robert H Mounce and William D Mounce. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. Scripture quotations identified nasb are from the New American Standard Bible®, copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lock- man Foundation. -

Master Class with George R.R. Martin: Selected Filmography 1 The

Master Class with George R.R. Martin: Selected Filmography The Higher Learning staff curate digital resource packages to complement and offer further context to the topics and themes discussed during the various Higher Learning events held at TIFF Bell Lightbox. These filmographies, bibliographies, and additional resources include works directly related to guest speakers’ work and careers, and provide additional inspirations and topics to consider; these materials are meant to serve as a jumping-off point for further research. Please refer to the event video to see how topics and themes relate to the Higher Learning event. Films and Television Series mentioned or discussed during the master class Game of Thrones (2011-2013). 2 seasons, 20 episodes. Creators: David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, U.S.A. Airs on HBO. Production Co.: HBO / Television 360 / Grok! Studio / Generator Entertainment / Bighead Littlehead / Embassy Films. The Twilight Zone (1959-1964). 5 seasons, 156 episodes. Creator: Rod Sterling, U.S.A. Originally aired on CBS. Production Co.: Cayuga Productions / CBS. Captain Video and His Video Rangers (1949-1955). 7 seasons, number of episodes unknown. Creator: James Caddiga, U.S.A. Originally aired on DuMont Television Network. Production Co.: DuMont Television Network. Rocky Jones, Space Ranger (1954). 2 seasons, 39 episodes. Creator: Roland D. Reed, U.S.A. Originally aired on DuMont Television Network. Production Co.: Roland Reed Productions / Space Ranger Enterprises. Tom Corbett, Space Cadet (1950-1955). 4 seasons, number of episodes unknown. Creator: unknown, U.S.A. Originally aired on CBS (1950), ABC (1951-1952), DuMont Television Network (1953-1954), and NBC (1954-1955). -

C Asper the Friendly Ghost Jumpchain

C asper The Friendly Ghost Jumpchain Welcome to the Worlds of Casper the Friendly Ghost... Alive or dead you'll be spending the next ten years dwelling here. The Worlds of Casper have one common theme, ghosts should be scary; those that won't be mean, will be disciplined. Here, Have 1000 Casper Points to get you started. Location To start off roll 1d8 to determine your location or pay 50cp to choose 1. 1950's Animated Casper – Noveltoons/HarveyToons. - This is the world of the original Casper cartoons, Casper 'lives' with his three 'Uncles' the Terrible Trio; Fatso, Fusso, and Lazo pressure poor Casper into being mean when he just want's to make friends. You may be able to make friends with the family of Richie Rich while you are here. 2. 1960's New Casper Cartoon Show – Casper and his friends, the ghost horse Nightmare, and Wendy the Good Little Witch, are all somewhat ostracized by their peers as they just want to be nice. This world features many elements from classic fantasy, enchanted forests, A Toyland, even Alien visitors. 3. 1970's Casper TV Specials by Hanna-Barbera - Casper Celebrated Both Halloween and Christmas with the Hanna-Barbera Gang. Yogi Bear, Snagglepuss, Huckleberry Hound et cetra. Why not visit Jellystone park while you're here? 4. 1990's Casper Film/The Spooktacular New Adventures of Casper series - This is the only version of Casper to have a Human Life to be remembered. C. McFadden is the son of a mysterious inventor and owner of Whipstaff Manor. -

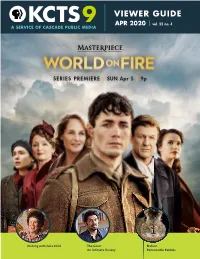

VIEWER GUIDE APR 2020 | Vol

VIEWER GUIDE APR 2020 | vol. 22 no. 4 A SERVICE OF CASCADE PUBLIC MEDIA SERIES PREMIERE | SUN Apr 5 | 9p Dishing with Julia Child The Gene: Nature: An Intimate History Remarkable Rabbits 1 Dishing with Julia Child series premiere FRI Apr 3 | 10p Julia Child was quirky – unpolished for television and irresistibly whimsical. More than 50 years after its debut, The French Chef remains important television. In this new series, some of today’s most popular celebrity chefs and food experts share personal insights and engage in lighthearted conversations as they screen – and delight in – some of Julia Child’s most beloved episodes. Featured celebrities include Martha Stewart, Jacques Pépin, Vivian Howard, Marcus Samuelsson, José Andrés, Eric Ripert and Rick Bayless. Masterpiece: World on Fire series premiere SUN Apr 5 | 9p This new series from Masterpiece is an emotionally gripping World War II drama that follows the intertwining fates of ordinary people in fi ve countries as they grapple with the eff ects of the war on their everyday lives. Staring Helen Hunt, Sean Bean and Jonah Hauer-King, the fi rst season of this series is set during the fi rst year of the war. The Gene: An Intimate History series premiere TUE Apr 7 | 8p This two-part series vividly brings to life the story of today’s revolution in medical science through tales of patients and doctors at the forefront of the search for genetic treatments. Presented by Ken Burns, the series also explores the compelling history of the discoveries that made modern treatments possible – and considers the ethical challenges raised by the ability to edit DNA with precision. -

Matthew Bardsley Writer

Matthew Bardsley Writer Matthew sold his first screenplay shortly before leaving Bristol University and has since worked extensively on assignments and original work. He was born in Toronto, Canada and retains dual British/Canadian citizenship. Agents St John Donald Associate Agent Jonny Jones [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0928 Credits In Development Production Company Notes ALL'S FAIR Monkey Kingdom 90' FILM MEMBER STATES Greenlit 3 x 60' Television Production Company Notes STRAWBERRY JOE BBC 60' Film LANDER'S WORLD BBC Original 60' Pilot FAMILY MAN BBC Original 60' Pilot THE GATECRASHER Carlton Adaptation: 1 x 60' DALZIEL & PASCOE BBC 1x 90' Treatment THE TROUBLE WITH MEN Sally Head Productions Original 6 x 60' Treatment LLANALLAN FM Sally Head Productions Original 60' Pilot United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes CAPITAL OFFENCE Touchpaper 90' Treatement SEASON TICKET Sally Head Productions Original 60' Pilot THE MOTTLEY CREW World Original 60' Pilot Producer: Ted Childs DEADLY ALLIANCE Tailormade Films/BBC Original 2 x 120' HOLBY CITY BBC PUSHING VINYL Zenith Original 60' Pilot THE BILL Talkback Thames 8 x 60' MAKING WAVES Carlton 4 x 60' FISH BBC/ Principle Pictures 4 x 60' MIT Thames 1 x 60' SWEET MEDICINE Carlton 2 x 60' PEAK PRACTICE Central 1 x 60' DANGERFIELD BBC 2 x 60' SPACE ISLAND ONE Bard/ SKY 5 x 60' EYE CONTACT North South/C4 30' Film CAPITAL CITY Euston Films 5 x 60' STYLE MONSTERS Island Visual -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number 150 25/01/10

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 150 25 January 2010 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 150 25 January 2010 Contents Introduction 3 Standards cases In Breach Steve Power at Breakfast Wave 105 (Solent and surrounding area), 3 December 2009, 05:30 4 Ruhaniat and Tib-e-Nabvi [this decision has now been removed from this Bulletin – see note at page 6] Venus TV, 9 September 2009, 12:05 6 The X Factor Results Show ITV 1, 25 October 2009, 20:00 7 Really Caught in the Act ITV4, 1 December 2009, 13:25 9 Yvette and Karl: Down on One Knee Living, 7 November 2009, 20:00 10 Retention of recordings ABS-CBN News Channel, 6 November 2009 11 Resolved The Early Morning Breakfast Show Pirate FM, 14 November 2009, 09:00 12 Fairness & Privacy cases There are no Fairness and Privacy Adjudications in this Bulletin. Other programmes not in breach 14 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 150 25 January 2010 Introduction The Broadcast Bulletin reports on the outcome of investigations into alleged breaches of those Ofcom codes which broadcasting licensees are required to comply. These include: a) Ofcom‟s Broadcasting Code (“the Code”) which took effect on 16 December 2009 and covers all programmes broadcast on or after 16 December 2009. The Broadcasting Code can be found at http://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv/ifi/codes/bcode/. Note: Programmes broadcast prior to 16 December 2009 are covered by the 2005 Code which came into effect on 25 July 2005 (with the exception of Rule 10.17 which came into effect on 1 July 2005). -

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 MAY/JUNE 2020 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 MAY/JUNE 2020 Virgin 445 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, Hoping as usual that you are all safe and well in these troubled times. Our cinema doors are still well and truly open, I’m pleased to say, the channel has been transmitting 24 hours a day 7 days a week on air with a number of premières for you all and orders have been posted out to you all every day as normal. It’s looking like a difficult few months ahead with lack of advertising on the channel, as you all know it’s the adverts that help us pay for the channel to be transmitted to you all for free and without them it’s very difficult. But we are confident we can get over the next few months. All we ask is that you keep on spreading the word about the channel in any way you can. Our audiences are strong with 4 million viewers per week , but it’s spreading the word that’s going to help us get over this. Can you believe it Talking Pictures TV is FIVE Years Old later this month?! There’s some very interesting selections in this months newsletter. Firstly, a terrific deal on The Humphrey Jennings Collections – one of Britain’s greatest filmmakers. I know lots of you have enjoyed the shorts from the Imperial War Museum archive that we have brought to Talking Pictures and a selection of these can be found on these DVD collections. -

Wolf Hall Free

FREE WOLF HALL PDF Hilary Mantel | 672 pages | 07 Jan 2010 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007351459 | English | London, United Kingdom Wolf Hall on MASTERPIECE on PBS Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Wolf Hall to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview Wolf Hall a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel. England in the s is a heartbeat from disaster. If the king dies without a male heir, the country could be Wolf Hall by civil war. The pope and most of Europe opposes him. Into this impasse steps Thomas Cromwell: a wholly original man, a charmer and a bully, both idealist and opportunist, astu England in the s is a heartbeat from disaster. Into this impasse steps Thomas Cromwell: a wholly original man, a charmer and a bully, both idealist and opportunist, astute in reading people, and implacable in his ambition. But Henry is volatile: one day tender, one day murderous. Cromwell helps him break the opposition, but what will be Wolf Hall price of his triumph? Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Thomas Cromwell 1Le Conseiller 1. Other Editions Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of Wolf Hall book, please sign up. Wolf Hall ask other readers questions about Wolf Hallplease sign up. Been on my shelf for four years - should I Wolf Hall it?? Vidhi Depends on what kind of reader you are. -

On Topophobia and the Horror of Rural Landscapes James Thurgill

33 A Fear of the Folk: On topophobia and the Horror of Rural Landscapes James Thurgill (The University of Tokyo) The so-called ‘unholy trinity’ (Scovell 2017: 8) designates a collection of horror films produced between 1968 and 1973--Witchfinder General (1968), The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), and The Wicker Man (1973). These films are described by Mark Gatiss in his A History of Horror series for the BBC (2010) as sharing ‘a common obsession with the British landscape, its folklore and superstitions’, and are generally regarded as the starting point for the folk horror subgenre. As central examples of folk horror cinema, these films approach the rural (British) landscape as a commonly understood and singular entity, a process mirrored in their portrayal of the folk who inhabit it; these ‘folk’ are unmodern, superstitious and, above all, capable of enacting extreme violence in order to conserve the rural idyll. Naturally, such framings are erroneous; pastoral landscapes exist as multiplicities, with widely varying assemblages of human and non-human actants performing diverse functions within their respective (regional) environments: ‘rurality is not homogeneous – different “countrysides” are different’ (Cloke 2003: 2). In fact, the landscapes that emerge from the ‘unholy trinity’ demonstrate an explicit diversity in the settings used for the films as well as in characters’ understandings of the rural spaces in which they dwell: village, field, and island. Whilst it has been noted that pastoral landscapes are integral to producing the unsettling aesthetic of folk horror (Barnett 2018; MacFarlane 2015; Packham 2018; Paciorek 2015; Scovell 2017), there remains no comprehensive treatment of the subject within commentary on the subgenre. -

Dennis Potter: an Unconventional Dramatist

Dennis Potter: An Unconventional Dramatist Dennis Potter (1935–1994), graduate of New College, was one of the most innovative and influential television dramatists of the twentieth century, known for works such as single plays Son of Man (1969), Brimstone and Treacle (1976) and Blue Remembered Hills (1979), and serials Pennies from Heaven (1978), The Singing Detective (1986) and Blackeyes (1989). Often controversial, he pioneered non-naturalistic techniques of drama presentation and explored themes which were to recur throughout his work. I. Early Life and Background He was born Dennis Christopher George Potter in Berry Hill in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire on 17 May 1935, the son of a coal miner. He would later describe the area as quite isolated from everywhere else (‘even Wales’).1 As a child he was an unusually bright pupil at the village primary school (which actually features as a location in ‘Pennies From Heaven’) as well as a strict attender of the local chapel (‘Up the hill . usually on a Sunday, sometimes three times to Salem Chapel . .’).2 Even at a young age he was writing: I knew that the words were chariots in some way. I didn’t know where it was going … but it was so inevitable … I cannot think of the time really when I wasn’t [a writer].3 The language of the Bible, the images it created, resonated with him; he described how the local area ‘became’ places from the Bible: Cannop Ponds by the pit where Dad worked, I knew that was where Jesus walked on the water … the Valley of the Shadow of Death was that lane where the overhanging trees were.4 I always fall back into biblical language, but that’s … part of my heritage, which I in a sense am grateful for.5 He was also a ‘physically cowardly’6 and ‘cripplingly shy’7 child who felt different from the other children at school, a feeling heightened by his being academically more advanced.