2017 Justice System Special Oversight Committee Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senators & Committees

Select Committees Hearing Rooms Committee on Committees Note: The ongoing replacement of Capitol heating, ventilation and Chair: Sen. Robert Hilkemann; V. Chair: Sen. Adam Morfeld air conditioning equipment requires temporary relocation of certain Senators & 1st District: Sens. Bostelman, Kolterman, Moser legislative offices and hearing rooms. Please contact the Clerk of the 2nd District: Sens. Hunt, Lathrop, Lindstrom, Vargas Legislature’sN Office (402-471-2271) if you have difficulty locating a 3rd District: Sens. Albrecht, Erdman, Groene, Murman particular office or hearing1st room. Floor Enrollment and Review First Floor Committees Chair: Sen. Terrell McKinney Account- ing 1008 1004 1000 1010 Reference 1010-1000 1326-1315 Chair: Sen. Dan Hughes; V. Chair: Sen. Tony Vargas M Fiscal Analyst H M 1012 W 1007 1003 W Members: Sens. Geist, Hilgers, Lathrop, Lowe, McCollister, 1015 Pansing Brooks, Slama, Stinner (nonvoting ex officio) 1402 1401 1016 Rules 1017 1308 1404 1403 1401-1406 1019 1301-1314 1023-1012 Chair: Sen. Robert Clements; V. Chair: Sen. Wendy DeBoer 1305 1018 Security Research 1306 Members: Sens. J. Cavanaugh, Erdman, M. Hansen, Hilgers (ex officio) 1405 1021 1406 Pictures of Governors 1022 Research H H Gift 1302 1023 15281524 1522 E E 1510 Shop Pictures of Legislators Info. 1529-1522 Desk 1512-1502 H E E H Special Committees* 1529 1525 1523 1507 1101 Redistricting 1104 Members: Sens. Blood, Briese, Brewer, Geist, Lathrop, Linehan, Lowe, W Bill Room Morfeld, Wayne 1103 Cafeteria Mail-Copy 1114-1101 1207-1224 Building Maintenance Center 1417-1424 1110 Self- 1107 Service Chair: Sen. Steve Erdman Copies Members: Sens. Brandt, Dorn, Lowe, McDonnell, Stinner W H W M 1113 1115 1117 1423 M 1114 Education Commission of the States 1113-1126 1200-1210 1212 N Members: Sens. -

September 2015 Nebraska Right to Life State Affiliate to the National Right to Life Committee

September 2015 Nebraska Right to Life State Affiliate to the National Right to Life Committee 404 S. 11th Street • P.O. Box 80410 • Lincoln, NE 68501 (402) 438-4802 • [email protected] • www.nebraskarighttolife.org UNDERCOVER VIDEOS SHOW SHOCKING REVELATIONS ABOUT HARVESTING ABORTED BABIES FOR POSSIBLE SALE In mid-July the first undercover personnel. Some show the “labs” inside video by The Center for Medical PP abortion facilities where PP techni- Progress came across social media cians and journalists posing as reps and exposed the shocking callous- from a tissue procurement company ness and candidness of Planned pick through bloody aborted baby parts, Parenthood Federation of America looking for organs and tissue. (PPFA) Affiliates personnel with The fifth video was filmed inside regard PP Affiliates’ harvesting of PP of the Gulf Coast’s mega clinic in aborted babies’ tissues and organs Houston. On camera their Director of for possible sale to a fetal tissue Research Melissa Farrell is caught procurement company. They have discussing their ability to deliver whole, been releasing one video a week intact babies for research. Inside the (one week there were two) and, at the PP “POC — Products of Conception” Coast is doing later-term abortions time of this writing, we have now seen lab we see more gruesome footage and the baby shown in this video was seven videos. Some are interviews of bloody baby parts being picked Continued on Page 3 with PP Affiliates and PPFA top level through by the lab tech. PP of the Gulf DOES NEBRASKA RIGHT TO LIFE HAVE A DEATH PENALTY POSITION? NO Q With the Legislature repealing the Death Penalty and the and non-sectarian. -

Filed a Lawsuit

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF LANCASTER COUNTY, NEBRASKA STATE OF NEBRASKA ex rel. DOUGLAS J. PETERSON, Attorney General, and SCOTT FRAKES, Case No. CI ________ Director of the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, COMPLAINT Plaintiffs, (Related Case No. CI 18-1026) v. SENATOR LAURA EBKE, Chairperson of the Judiciary Committee of the Nebraska Legislature, SENATOR DAN WATERMEIER, SENATOR ERNIE CHAMBERS, SENATOR ROY BAKER, SENATOR MATT HANSEN, SENATOR BOB KRIST, SENATOR ADAM MORFELD, SENATOR PATTY PANSING BROOKS, SENATOR STEVE HALLORAN, SENATOR KATE BOLZ, SENATOR SUE CRAWFORD, SENATOR DAN HUGHES, SENATOR JOHN KUEHN, SENATOR TYSON LARSON, SENATOR JOHN MCCOLLISTER, SENATOR JIM SCHEER, and PATRICK J. O’DONNELL, Clerk of the Nebraska Legislature, Defendants. Plaintiffs State of Nebraska ex rel. Douglas J. Peterson, Attorney General, and Scott Frakes, Director of the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, for their claims against Defendants, in their official capacities, allege the following: 1 PARTIES PLAINTIFFS 1. Plaintiff Douglas J. Peterson is the Attorney General of the State of Ne- braska. 2. Plaintiff Scott Frakes is the Director of the Nebraska Department of Correc- tional Services. DEFENDANTS 3. All of the Defendants are sued in their official capacities. 4. Senator Laura Ebke is, and was at all times relevant herein, a Nebraska State Senator and Chairperson of the Judiciary Committee of the Nebraska Legisla- ture. 5. Senator Ernie Chambers is, and was at all times relevant herein, a Nebraska State Senator. Senator Chambers is the only one of the defendants who is both a member of the Judiciary Committee and the Executive Board of the Legislative Coun- cil. -

United for Health PAC 2015 U.S. Political Contributions & Related

2015 US Political Contributions & Related Activity Report LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN Our workforce of more than 225,000 people is dedicated to helping people live healthier lives and helping to make the health system work better for everyone. Technological change, new collaborations, market dynamics and a shift toward building a more modern infrastructure for health care are driving rapid evolution of the health care market. Federal and state policy-makers, on behalf of their constituents and communities, continue to be deeply involved in this changing marketplace. UnitedHealth Group remains an active participant in the political process to provide proven solutions that enhance the health system. The United for Health PAC is an important component of our overall strategy to engage with elected officials and policy-makers, to communicate our perspectives on priority issues, and to share with them our capabilities and innovations. The United for Health PAC is a nonpartisan political action committee supported by voluntary contributions from eligible employees. The PAC supports federal and state candidates who align with our business objectives to increase quality, access, and affordability in health care, in accordance with applicable election laws and as overseen by the UnitedHealth Group Board of Directors’ Public Policy Strategies and Responsibility Committee. UnitedHealth Group remains committed to sharing with federal and state governments the advances and expertise we have developed to improve the nation’s overall health and well-being. -

Annual Report

2015 ANNUAL REPORT Care PAC is a political fund of the Nebraska Health Care Association Dear friends and colleagues, We are happy to present the 2015 Care PAC Annual Report! Upon reviewing the next few pages, you will see that 2015 was another record-breaking year in terms of the amount raised. Care PAC raised $50,449, an increase of 18 percent from the previous year. Together we are truly making a difference. 2015 was an important year in Nebraska politics. Your Care PAC contributions helped new and current state legislators understand the complexities that long-term care providers face on a daily basis. Building a strong political action fund is the key to being a political powerhouse, so we can now turn our attention toward helping to elect the next wave of state legislators in 2016. When it comes to the political process, we can choose to stay disconnected and allow others to make decisions for us; or we can choose to become engaged and be the masters of our own destiny. Part of engaging in the political process is the ability to financially contribute to candidates who share our vision. Not only does this help like-minded candidates get elected, but also signals to the legislature that we’re serious. It helps us get a seat at the table when long-term care and other issues important to you are discussed. Please assist us as we work on your behalf by contributing to NHCA’s Care PAC. Our entire field will be better thanks to your generosity. Sincerely, Shari Terry, Co-Chair Care PAC Jayne Prince, Co-Chair Care PAC 2016 Care PAC Committee Jayne Prince, Co-Chair ............The Willows ................................................. -

2020 Nebraska Primary Election Guide Children’S Hospital & Medical Center

2020 Nebraska Primary Election Guide Children’s Hospital & Medical Center 1 President of the United States Donald Trump Age: 73 Occupation: POTUS Political Party: Republican Website: www.donaldjtrump.com Legislative Priorities: “America First” – renegotiate trade, support for veterans, keep jobs in America, protect borders. Bill Weld Age: 75 Occupation: Former Governor of Massachusetts, attorney Political Party: Republican Website: www.weld2020.com Legislative Priorities: End trade wars, technical education and retraining for a healthier economy and job growth, simpler tax code, support middle class. Joe Biden Age: 77 Occupation: Former Vice President of the U.S. Political Party: Democrat Website: www.joebiden.com Legislative Priorities: Address racial, gender and other inequalities, invest in housing, expand the Affordable Care Act, invest in education . 2 U.S. Senate Ben Sasse Age: 48 Occupation: U.S. Senator (one-term) Political Party: Republican Address: PO Box 83978, Lincoln Website: www.teamsasse.com Legislative Priorities: Pro Life, expanding trade, increasing border security, national security, combating the COVID-19 virus. Matt Innis Age: 49 Occupation: Owner, electrical wiring and cabling business. Honorably discharged from the Marine Corps in 1999. Political Party: Republican Address: 6277 West Leealan Lane, Crete Website: www.mattinnis4senate.com Legislative Priorities: Agriculture, Country of Origin Labeling for Meat (COOL), Immigration. Chris Janicek Age: 56 Occupation: Small business owner, property investor Political Party: Democrat Address: 405 N. 40th Street, Omaha Website: http://www.janicekforsenate2020.com/ Legislative Priorities: Health care for all Americans, single payer health care, investing more into education. Dennis Frank Macek Age: 79 Occupation: Literary writer Political Party: Democrat Address: 3330 M. Street, Lincoln Website: www.macekforsenate.com Legislative Priorities: Renewable energy, affordable healthcare and food security amidst global climate changes. -

Nebraska Legislature: How They Voted for the Early Advantage of Children in the 104Th Legislative Session 2015 – 2016

Nebraska Legislature: How they Voted for the Early Advantage of Children in the 104th Legislative Session 2015 – 2016 Dear Nebraska Friends and Colleagues, July 2016 We have pulled together the following information to indicate how Nebraska’s State Senators voted for children on select occasions during the 104th Legislative Session. These selected votes were based on legislative proposals critical to impacting working families and their children. These proposals were priorities of the Holland Children’s Movement related to issues of health, education and economic stability. We have included a percentage of each senator’s support of these priorities based on their votes on specific legislative measures throughout 2015-16. These voting records do not indicate other legislative activities of interest to Nebraska’s children, such as committee votes or bills introduced. We are pleased to report that more than half of all senators voted in support of the position of the Holland Children’s Movement 80% or more of the time. We would like to extend our sincere appreciation to all of our senators for their dedication to public service and our gratitude for the actions taken to make Nebraska a national leader in opportunities for all children. We hope you will continue to support efforts to tackle the root causes of family poverty and assure that every child in Nebraska will have the support and opportunities they need to reach their full potential. Sincerely, John J. Cavanaugh Chief Operating Officer 1700 Farnam St, Ste 1090 Omaha, NE 68102 2016 -

Jan. 7-9, 2015

UNICAMERAL UPDATE Stories published daily at Update.Legislature.ne.gov Vol. 38, Issue 1 / Jan. 7 - 9, 2015 Legislature convenes, elects leaders Senators who were elected or re-elected in November were sworn into office Jan. 7, the opening day of the 2015 legislative session. he 104th Nebraska Legislature Term limits also opened up leader- Omaha to chair the Business and convened at 10:00 a.m. on Jan. ship positions on 10 of the Legisla- Labor Committee; Sen. Tyson Larson T 7 for the 90-day first session. ture’s 14 standing committees. of O’Neill to chair the General Affairs Seventeen new members were sworn Sen. Jerry Johnson of Wahoo de- (continued page 3) into office and senators were elected feated Bancroft Sen. Lydia to serve as chairpersons of the Legis- Brasch as chairperson lature’s standing committees. of the Agriculture Com- Kearney Sen. Galen Hadley de- mittee. Johnson said his feated Sen. Colby Coash of Lincoln 42 years of experience in in the race to replace outgoing speaker agribusiness would help of the Legislature, York Sen. Greg him meet the challenge Adams, who left the Legislature due of expanding the state’s to term limits. livestock industry. Hadley said one of his priorities “My focus will be to would be to assist new committee build agriculture and to leaders in their work. As the former build Nebraska,” Johnson chairperson of the Revenue Com- said. mittee and the Tax Modernization Elected in uncontest- Committee, Hadley said he would ed races were: Sen. Jim bring vital experience to the position Scheer of Norfolk to chair of speaker. -

Session Review 2017 Volume XL, No

THE 105TH NEBRASKA LEGISLATURE FIRST SESSION Unicameral Update Session Review 2017 Volume XL, No. 21 2017 Session Review Contents Agriculture .......................................................................................... 1 Appropriations .................................................................................... 2 Banking, Commerce and Insurance .................................................. 4 Business and Labor ........................................................................... 6 Education ............................................................................................ 8 Executive Board ............................................................................... 11 General Affairs .................................................................................. 12 Government, Military and Veterans Affairs ...................................... 13 Health and Human Services ............................................................ 16 Judiciary ........................................................................................... 20 Natural Resources ............................................................................ 24 Retirement Systems ......................................................................... 26 Revenue ............................................................................................ 27 Transportation and Telecommunications ........................................ 30 Urban Affairs .................................................................................... -

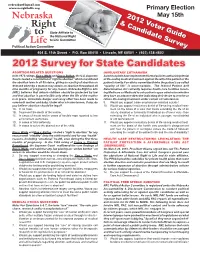

2012 Primary Election

[email protected] www.nerighttolife.org Primary Election Nebraska 2012 V May 15th Right & Candidateoter S Gurveyuide to State Affiliate to the National Right Life to Life Committee Political Action Committee 404 S. 11th Street • P.O. Box 80410 • Lincoln, NE 68501 • (402) 438-4802 2012 Survey for State Candidates ABORTION-RELATED QUESTIONS INVOLUNTARY EUTHANASIA In its 1973 rulings, Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton, the U.S. Supreme Some hospitals have implemented formal policies authorizing denial Court created a constitutional “right to abortion” which invalidated of life-saving medical treatment against the will of the patient or the the abortion laws in all 50 states, giving us a policy of abortion on patient’s family if an ethics committee thinks the patient’s so-called demand whereby a woman may obtain an abortion throughout all “quality of life” is unacceptable. The federal Patient Self nine months of pregnancy for any reason. Nebraska Right to Life Determination Act currently requires health care facilities receiv- (NRL) believes that unborn children should be protected by law ing Medicare or Medicaid to ask patients upon admission whether and that abortion is permissible only when the life of the mother they have an advance directive indicating their desire to receive or is in grave, immediate danger and every effort has been made to refuse life-saving treatment under certain circumstances. save both mother and baby. Under what circumstances, if any, do 9. Would you support a ban on physician-assisted suicide? you believe abortion should be legal? 10. Would you oppose involuntary denial of life-saving medical treat- 1A. -

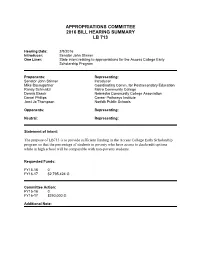

2016 Appropriations Committee Bill Summaries

APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEE 2016 BILL HEARING SUMMARY LB 713 Hearing Date: 2/9/2016 Introducer: Senator John Stinner One Liner: State intent relating to appropriations for the Access College Early Scholarship Program Proponents: Representing: Senator John Stinner Introducer Mike Baumgartner Coordinating Comm. for Postsecondary Education Randy Schmailzl Metro Community College Dennis Baack Nebraska Community College Association Daniel Phillips Career Pathways Institute Jami Jo Thompson Norfolk Public Schools Opponents: Representing: Neutral: Representing: Statement of Intent: The purpose of LB713 is to provide sufficient funding in the Access College Early Scholarship program so that the percentage of students in poverty who have access to dualcredit options while in high school will be comparable with non-poverty students. Requested Funds: FY15-16 0 FY16-17 $2,795,424 G Committee Action: FY15-16 0 FY16-17 $250,000 G Additional Note: APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEE 2016 BILL HEARING SUMMARY LB 715 Hearing Date: 2/11/2016 Introducer: Senator John Stinner One Liner: Provide for transfers from the General Fund to the Nebraska Cultural Preservation Endowment Fund Proponents: Representing: Senator John Stinner Introducer Robert Nefsky Nebr Arts Council & Nebr Cultural Endowment Chris Sommerich Humanities Nebraska Suzanne Wise Nebraska Arts Council Opponents: Representing: Neutral: Representing: Statement of Intent: The purpose of this bill is to continue funding the Nebraska Cultural Preservation Endowment Fund not to exceed $500,000.00 beginning on December 31, 2017, and continuing through December 31, 2026. Annual contributions to the Endowment Fund must be matched by private funds raised by the Nebraska Arts Council and the Nebraska Humanities Council. Current funding is $750,000.00 so this bill lowers the annual endowment request by $250,000.00. -

Legislative Wrap-Up

Legislative Wrap-Up 2016 by the numbers 2016 Legislative Session by the numbers The Nebraska Hospital Association’s (NHA) public policy and Composition of 104th Legislature advocacy priorities are driven by a vision that every Nebraskan has access to affordable, safe, high-quality health care. Through effective leadership and member participation, the NHA continues to develop a unified voice to establish effective health care policy in Nebraska. The NHA is committed to creating and maintaining a financial and regulatory environment in which hospitals and health care systems can provide the right care, at the right time. This involves collaborating with members, policymakers and other health care partners in advocating for our top priorities. The health care industry touches many aspects of public policy, and the NHA monitors a broad spectrum of issues on behalf of its members. In 2016, the NHA Advocacy Team was deeply involved with legislation affecting workforce development, insurance, taxation, employment, academic research and health care. Nebraska Unicameral Legislature 104th Legislature, Second Session • 60-day session convened January 6, 2016 38 Men 11 Women • 445 bills introduced • 86 Bills of Interest to the NHA’s members were identified, covering a wide range of issues The NHA initially: 36 Republicans 12 Democrats 1 Independent - Supported 15 - Opposed 4 - Monitored 65 - Neutral positions 0 Sen. Laura Ebke (District 32) • The NHA submitted written testimony on 10 bills changed per political party and testified in-person on 8