Model of Creativity in Commercial Pop Music at P&E Studios in the 1990S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF (Author Accepted Manuscript)

5 weaPons of mass seduction Performing Pop Masculinity To all intents and purposes Harry Styles, unofficial frontman of internationally renowned boy band One Direction, could easily be mistaken for a young Mick Jagger (see Figure 5.1). The men’s good looks, broad smiles, matching windswept hair styles and shared fashion sensibilities bridge a 51-year age gap. Both are singers who have enjoyed the adoration of a passionate fan following, yet in terms of the version of masculinity each represents, the two could not be more different. While Jagger is openly admired by both sexes, few men admit to being fans of Harry Styles whose following is commonly depicted as restricted to teen and pre-teen females. Unlike the older man, Styles radiates a wholesome, good humoured exuberance, appears to genuinely like female company and is never happier than when exalting the women in his life. He also differs from the Rolling Stones leader in showing a marked preference for older female partners, whereas Jagger figure 5.1 Harry Styles. 84 Weapons of Mass Seduction is always seen in the company of much younger women.1 Jagger’s androgy- nous charm is tinged with danger and more than a hint of misogyny: he has a reputation for treating his partners callously, and from the outset, chauvinism themes of mistrust permeated the Rolling Stones’ songbook.2 The younger singer is also androgynous but his failure to comply with core characteristics of normative masculinity underscores much of the antipathy directed towards by critics, highlighting deeply entrenched prejudice against those who fail to comply with accepted expressions of gender. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Jall 20 Great Extended Play Titles Available in June

KD 9NoZ ! LO9O6 Ala ObL£ it sdV :rINH3tID AZNOW ZHN994YW LIL9 IOW/ £L6LI9000 Heavy 906 ZIDIOE**xx***>r****:= Metal r Follows page 48 VOLUME 99 NO. 18 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT May 2, 1987/$3.95 (U.S.), $5 (CAN.) Fla. Clerk Faces Obscenity Radio Wary of Indecent' Exposure Charge For Cassette Sale FCC Ruling Stirs Confusion April 20. She was charged with vio- BY CHRIS MORRIS lating a state statute prohibiting ington, D.C., and WYSP Philadel- given further details on what the LOS ANGELES A Florida retail "sale of harmful material to a per- BY KIM FREEMAN phia, where Howard Stern's morn- new guidelines are, so it's literally store clerk faces felony obscenity son under the age of 18," a third -de- NEW YORK Broadcasters are ex- ing show generated the complaints impossible for me to make a judg- charges for selling a cassette tape gree felony that carries a maximum pressing confusion and dismay fol- that appear to have prompted the ment on them as a broadcaster." of 2 Live Crew's "2 Live Crew Is penalty of five years in jail or a lowing the Federal Communications FCC's new guidelines. According to FCC general coun- What We Are" to a 14- year -old. As a $5,000 fine. Commission's decision to apply a "At this point, we haven't been (Continued on page 78) result of the case, the store has The arrest apparently stems from broad brush to existing rules defin- closed its doors. the explicit lyrics to "We Want ing and regulating the use of "inde- Laura Ragsdale, an 18- year -old Some Pussy," a track featured on cent" and /or "obscene" material on part-time clerk at Starship Records the album by Miami-based 2 Live the air. -

East 17 Around the World Mp3, Flac, Wma

East 17 Around The World mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Around The World Country: Italy Released: 1994 Style: House MP3 version RAR size: 1543 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1669 mb WMA version RAR size: 1437 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 469 Other Formats: ADX AUD AU MOD TTA AHX MPC Tracklist Hide Credits Around The World (Overworld Vocal) A1 Mixed By – Lee MonteverdeRemix – Development CorporationRemix [Credited] – Johnny 6:22 Jay, Neil Claxton Around The World (Overworld Dub) A2 Mixed By – Lee MonteverdeRemix – Development CorporationRemix [Credited] – Johnny 6:18 Jay, Neil Claxton Around The World (Global House Mix) B1 6:22 Remix, Producer [Additional Production] – Ben Liebrand Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – London Records 90 Ltd. Mixed At – Moonraker Studios Phonographic Copyright (p) – London Produced For – BiffCo Published By – Porky Publishing Published By – PolyGram Music Credits Producer – Richard Stannard Producer [Assisitant] – Matt Rowe Written-By – Harvey*, Rowe*, Stannard*, Mortimer* Notes 33 Mix Made In Italy Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side A runout machine stamped): 857543 1 1 520 Matrix / Runout (Side B runout machine stamped): 857543 1 2 520 Rights Society: S.I.A.E. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year London Around The LONCD 349, Records, LONCD 349, East 17 World (CD, UK 1994 869 559-2 London 869 559-2 Single) Records London Around The LONCS 349, 869 Records, LONCS 349, 869 UK & East 17 World (Cass, 1994 558.4 London 558.4 Europe Single) -

Our First Covid Confirmation

Price £1 when sold OUR FIRST COVID CONFIRMATION How strange it was to have a much reduced congregation PARTNERSHIP WITH WITHYCOMBE with hymns and parts of the service sung by the choir RALEIGH MISSION COMMUNITY with the participants wearing masks. However it was a great joy to welcome the Diocesan Bishop, Robert Following an invitation from the Bishop of Crediton and Atwell to Holy Trinity recently to celebrate the entry of the Archdeacon of Exeter, leaders in our Mission our candidates into full membership of the Church. Community have been undertaking preliminary discussions with the leaders of Withycombe Raleigh Those confirmed were Lucy Netherton, Caylin-Ora Mission Community with a view to exploring an Williams, James Halse, Chris Hawkins, and Katie amalgamation of our six church congregations into one Baughan-Martin Anglican family. The diocesan view is that doing mission and ministry together, as one team, will allow us to offer more ministry choices to the people of the Exmouth area. THE RECTOR HAS WRITTEN TO US ALL It will also allow us to make the most efficient use of our resources and will likely increase the impact of the Steves letter to our congregations can be found available clergy that we have in the town. On the 24 on page 19. Please do read it as it gives full details August the PCCs of Lympstone, Littleham-cum-Exmouth of the way our Church life will be shaped as we and Withycombe Raleigh will meet at Holy Trinity move out of the Covid restrictions. Especially as Church to further explore what coming together might Covid has not gone away (nor is it likely to do) mean for us all. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Workbridge Activity Pack

Workbridge Activity Pack Issue 8 Inside this pack you will find: 1. 40 years of Workbridge music quiz 2. Easy colouring pages 3. Ice cream flavours word search 4. Very hard summer word search 5. Practice mindfulness 6. Origami lion – see inserted paper Workbridge Activity Pack. Email a photo of your completed activities to [email protected] 40 Years of music through the decades 1980's 1. What year was Live Aid? A. 1989 B. 1985 C. 1983 2. In which iconic music video do Queen parody Coronation Street? A. I want to break free B. We will rock you C. Bohemian Rhapsody 3. Who went straight to number one in 1981 with "Stand and deliver"? A. Adam Bird B. Adam Ant C. Adam Wasp 4. Which famous actor was waiting for Bananarama in 1984? A. Al Pachino B. Jack Nicholson C. Robert De Niro 5. Which U2 album became the fastest selling in British history when released in 1987? A. The Joshua Tree B. The Apple Tree C. The Pear Tree 6. Which band was waiting for a letter from America? A. The Stray Cats B. The Proclaimers C. The Beatles 7. What was the name of Michael Jackson's first solo UK hit? A. ABC B. One day in your life C. Ben 1990’s 8. Which Scottish band had a 1985 hit with "Don't you forget about me"? A. Annie Lenox B. Sheena Easton C. Simple Minds 9. What is the name of Britney Spears first single released in 1998? A. Baby one more time B. -

Donna Summer I Don't Wanna Get Hurt (Extended Version) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Donna Summer I Don't Wanna Get Hurt (Extended Version) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Funk / Soul Album: I Don't Wanna Get Hurt (Extended Version) Country: Europe Released: 1989 Style: Synth-pop, Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1778 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1954 mb WMA version RAR size: 1691 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 407 Other Formats: MP2 AHX FLAC WMA APE DTS ADX Tracklist Hide Credits I Don't Wanna Get Hurt (Extended Version) Backing Vocals – Dee Lewis, Mae McKenna, Mike StockDrums – A Linn*Engineer – Karen A 6:58 Hewitt, YoyoGuitar – Matt AitkenKeyboards – George De Angelis, Matt Aitken, Mike StockMixed By – Mixmaster Phil Harding*Producer, Written-By – Stock/Aitken/Waterman* I Don't Wanna Get Hurt (Instrumental) Backing Vocals – Dee Lewis, Mae McKenna, Mike StockDrums – A Linn*Engineer – Karen B1 4:45 Hewitt, YoyoGuitar – Matt AitkenKeyboards – George De Angelis, Matt Aitken, Mike StockMixed By – Mixmaster Phil Harding*Producer, Written-By – Stock/Aitken/Waterman* Dinner With Gershwin B2 4:38 Co-producer [Associate Producer], Written-By – Brenda Russell Producer – Richard Perry Companies, etc. Made By – WEA Musik GmbH Published By – All Boys Music Ltd. Published By – Warner Chappell Ltd. Credits Design – ADC Production Other [Hair] – Andrene At Vidal Sassoon Other [Styling] – Kelly Cooper Photography By – Lawrence Lawry Notes A & B1: Recorded at PWL Donna's vocals were recorded using the Calrec Soundfield Microphone Published by All Boys Music Ltd. Original version available on the Warner Bros. album "Another Place And Time" 255976-1 ℗ 1989 Warner Bros. Records Inc. for the U.S. & WEA International Inc. -

Issue 195.Pmd

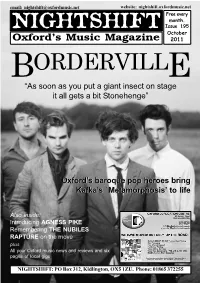

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 195 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2011 BORDERVILLE “As soon as you put a giant insect on stage it all gets a bit Stonehenge” Oxford’sOxford’s baroquebaroque poppop heroesheroes bringbring Kafka’sKafka’s `Metamorphosis’`Metamorphosis’ toto lifelife Also inside: Introducing AGNESS PIKE Remembering THE NUBILES RAPTURE on the move plus All your Oxford music news and reviews and six pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Truck Store is set to bow out with a weekend of live music on the 1st and 2nd October. Check with the shop for details. THE SUMMER FAYRE FREE FESTIVAL due to be held in South Park at the beginning of September was cancelled two days beforehand TRUCK STORE on Cowley Road after the organisers were faced with is set to close this month and will a severe weather warning for the be relocating to Gloucester Green weekend. Although the bad weather as a Rapture store. The shop, didn’t materialise, Gecko Events, which opened back in February as based in Milton Keynes, took the a partnership between Rapture in decision to cancel the festival rather Witney and the Truck organisation, than face potentially crippling will open in the corner unit at losses. With the festival a free Gloucester Green previously event the promoters were relying on bar and food revenue to cover occupied by Massive Records and KARMA TO BURN will headline this year’s Audioscope mini-festival. -

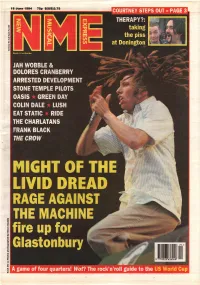

1994.06.18-NME.Pdf

INDIE 45s US 45s PICTURE: PENNIE SMITH PENNIE PICTURE: 1 I SWEAR........................ ................. AII-4-One (Blitzz) 2 I’LL REMEMBER............................. Madonna (Maverick) 3 ANYTIME, ANYPLACE...................... Janet Jackson (Virgin) 4 REGULATE....................... Warren G & Nate Dogg (Outburst) 5 THE SIGN.......... Ace Of Base (Arista) 6 DON’TTURN AROUND......................... Ace Of Base (Arista) 7 BABY I LOVE YOUR WAY....................... Big Mountain (RCA) 8 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD......... Prince(NPG) 9 YOUMEANTHEWORLDTOME.............. Toni Braxton (UFace) NETWORK UK TOP SO 4Ss 10 BACK AND FORTH......................... Aaliyah (Jive) 11 RETURN TO INNOCENCE.......................... Enigma (Virgin) 1 1 LOVE IS ALL AROUND......... ...Wet Wet Wet (Precious) 37 (—) JAILBIRD............................. Primal Scream (Creation) 12 IFYOUGO ............... ....................... JonSecada(SBK) 38 38 PATIENCE OF ANGELS. Eddi Reader (Blanco Y Negro) 13 YOUR BODY’S CALLING. R Kelly (Jive) 2 5 BABYI LOVE YOUR WAY. Big Mountain (RCA) 14 I’M READY. Tevin Campbell (Qwest) 3 11 YOU DON’T LOVE ME (NO, NO, NO).... Dawn Penn (Atlantic) 39 23 JUST A STEP FROM HEAVEN .. Eternal (EMI) 15 BUMP’N’ GRIND......................................R Kelly (Jive) 4 4 GET-A-WAY. Maxx(Pulse8) 40 31 MMMMMMMMMMMM....... Crash Test Dummies (RCA) 5 7 NO GOOD (STARTTHE DANCE)........... The Prodigy (XL) 41 37 DIE LAUGHING........ ................. Therapy? (A&M) 6 6 ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS.. Absolutely Fabulous (Spaghetti) 42 26 TAKE IT BACK ............................ Pink Floyd (EMI) 7 ( - ) ANYTIME YOU NEED A FRIEND... Mariah Carey (Columbia) 43 ( - ) HARMONICAMAN....................... Bravado (Peach) USLPs 8 3 AROUNDTHEWORLD............... East 17 (London) 44 ( - ) EASETHEPRESSURE................... 2woThird3(Epic) 9 2 COME ON YOU REDS 45 30 THEREAL THING.............. Tony Di Bart (Cleveland City) 3 THESIGN.,. Ace Of Base (Arista) 46 33 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD. -

Iiusicweek for Everyone in the Business of Music 16 SEPTEMBER

iiusicweek For Everyone in the Business of Music 16 SEPTEMBER 1995 £3.10 Simply Red the new single 'Fairground' Release date 18th September Formats: 2CDs, Cassette CD1 includes live tracks CD2 includes remixes w thusfcwe For Everyone in the Business of Music 16 SEPTEMBER 1995 THIS WEEK Black retumsto EMI as MD 4 Help wi He says his former colleague was the Warners and am now looking At 33, Black joins a growing list of agamsttjme Clive Black has finally been installed only"When candidate Manchester for his oldjob. United were -------theEMI. challenges Besides, ofJF- my put new r youthfu!industry, managingalongside directors MCA's in Nickthe lOBlur ingas managing weeks of spéculation. director of EMI UK, end- ers,champions, but you they don't tried change to change a winning play- Cecillon adds that I mldn't refuse." Phillips,RCA's Hugh 32, Goldsmith,_35,Epic's Rob Stringer, BMG misic _33, iWadsworth the company he left at the beginning of between' " ' us ays. "The ' ' îtry' Works inhis A&R new will job. be an"I aci division président Jeremy Marsh, 35, 12PRS:agm department,last year following most recently10 years inas itshead A&R of teamBlack again. wf ■ork alongside the tv UKandthekeytothfParlophone to be the signais s been WEA A&R Ton; il b managingand Roger directors Lewis, A&R drivenguy - probablyand becaus tl replacesdirector Jeanfor theFran | areporting daily basis. directly Cecillon to stresses him,"usiness he says.- tlu for Aftera manager two years at Intersong he moved Musicon to h I vacated the positioi will be given a free rein, "My mesf raftBlack of acts was to responsible the label in for his bringing last spell a movingWEA, to EMIwhose in 1984.managing di danceat EMI actUK, Markand at MorrisonWEA, he signedand teennew Moira BeUas says she wishes Black i group Optimystic.