Did Hospital Competition in the English NHS Save Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burton Role Name Brief Biography Panel Chair Ruth May Dr

Burton Role Name Brief Biography Panel Chair Ruth May Dr Ruth May is NHS England Regional Director of Nursing for Midlands and East. Her previous roles include Chief Nurse for NHS Midlands and East and Chief Nurse for NHS East of England. Ruth has a theatre nursing background and more than 20 years experience of working in the NHS. Patient/Public Representative Norma Armston Norma Armston has a wide range of experience as a patient/carer representative at both local and national level. She has been involved in reviewing cancer services and was a lay assessor in the Clinical Commissioning Group authorisation process. Patient/Public Representative Alan Keys Alan Keys is Lay Member for PPI on the board of High Weald Lewes Havens CCG. He is also a member of various other groups including the British Heart Foundation Prevention and Care Reference. Patient/Public Representative Leon Pollock Leon Pollock is a management consultant with over 30 years experience during which he has assisted more than 250 organisations, including 20 NHS trusts. He is Lay Adviser for Health Education West Midlands and Lay Assessor for the NHS Commissioning Board. Doctor Balraj Appedou Balraj Appedou is a consultant in anaesthesia and intensive care medicine at the Peterborough and Stamford Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Balraj is currently Lead for Clinical Governance in the Theatres Anaesthesia and Critical Care Medicine Directorate. Balraj has also been the Patient Safety Champion in the Trust. Doctor Mike Lambert Mr. Mike Lambert is a consultant at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital and Honorary Senior Lecturer at Norwich Medical School. -

NHS Reorganisation After the Pandemic

EDITORIALS BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.m4468 on 18 November 2020. Downloaded from Health Foundation, London, UK [email protected] NHS reorganisation after the pandemic Cite this as: BMJ 2020;371:m4468 Major structural change should not be part of the plan for recovery http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4468 Published: 18 November 2020 Hugh Alderwick head of policy Before covid-19 hit, national NHS bodies had asked the day-to-day workings of the NHS—something the 1 the government to make changes to NHS legislation. 2012 act sought to loosen. These changes were designed to make it easier for NHS England has become the de facto headquarters NHS organisations in England to collaborate to plan for NHS strategy under Simon Stevens, its chief and deliver services—including through establishing executive. The previous health secretary, Jeremy joint committees between commissioners and 2 Hunt, has said he never felt he “lacked a power to providers. Since then, government and the NHS have 9 give direction” to the NHS under the 2012 act. But been focused on managing covid-19. Proposals for perhaps the incumbent feels less powerful. Reform new legislation were temporarily shelved. to bring NHS England under closer political control But not for long: legislation for the NHS in England may also help build a narrative, ahead of any covid-19 seems to be back on the agenda. Media stories public inquiry, that arm’s length bodies—not emerged in the summer that the prime minister was government—are to blame for England’s pandemic considering proposals for a major NHS performance. -

Board of Directors - Open

Board of Directors - Open Date: 12 August 2020 Item Ref: 05 TITLE OF PAPER Chief Executive’s Report TO BE PRESENTED BY Jan Ditheridge ACTION REQUIRED The Board are asked to consider the impact and opportunity of the letter from Sir Simon Stevens and Amanda Pritchard regarding the third phase of the NHS response to CoVid on our strategic priorities and risks. The Board are asked to approve the recommendation re Executive lead for Inequalities. The Board are asked if there are any other issues that arise from the letter from Sir Simon Stevens and Amanda Pritchard we should consider. The Board are asked to consider the National Guardian Freedom to Speak Up Index Report 2020 and if they feel confident where and how we are addressing the issues it raises for us. The Board are asked to consider the NHS People Plan 2020/21, and where we may want the People Committee to focus attentions as an organisation, given our risks and challenges and as a contributor to our health and care system. The Board are asked to consider the direction of travel of the Accountable Care Partnership; and to understand the key priorities and how they relate to our own transformation programme. The Board are asked to acknowledge the Board role changes, consider any opportunities or risks within the changes and join me in thanking individuals for their contributions and wish them well where they have changed or moved into different roles. OUTCOME To update the Board on key policies, issues and events and to stimulate debate regarding potential impact on our strategy and levels of assurance. -

UNDERSTANDING the NEW NHS a Guide for Everyone Working and Training Within the NHS 2 Contents 3

England UNDERSTANDING THE NEW NHS A guide for everyone working and training within the NHS 2 Contents 3 NHS ENGLAND INFORMATION READER BOX Introduction 4 Directorate ◆ The NHS belongs to us all Medical Operations Patients and information Nursing Policy Commissioning development Foreword (Sir Bruce Keogh) 5 Finance Human resources NHS values 6 Publications Gateway Reference: 01486 ◆ NHS values and the NHS Constitution Document purpose Resources ◆ An overview of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 Document name Understanding The New NHS Structure of the NHS in England 8 Author NHS England ◆ The structure of the NHS in England Publication date 26 June 2014 ◆ Finance in the NHS: your questions answered Target audience Running the NHS 12 ◆ Commissioning in the NHS Additional circulation Clinicians working and training within the NHS, allied ◆ Delivering NHS services list health professionals, GPs ◆ Health and wellbeing in the NHS Description An updated guide on the structure and function of Monitoring the NHS 17 the NHS, taking into account the changes of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 ◆ Lessons learned and taking responsibility ◆ Regulation and monitoring in the NHS Action required None Contact details for Dr Felicity Taylor Working in the NHS 20 further information National Medical Director's Clinical ◆ Better training, better care Fellow, Medical Directorate Skipton House NHS leadership 21 80 London Road SE1 6LH ◆ Leading healthcare excellence www.england.nhs.uk/nhsguide/ Quality and innovation in the NHS 22 ◆ High-quality care for all Document status This is a controlled document. While this document may be printed, the The NHS in the United Kingdom 24 electronic version posted on the intranet is the controlled copy. -

NHS Long Term Plan (Pdf)

Long-Term Plan Long-Term Plan Long-Term The NHS Long Term Plan Plan Long-Term Plan #NHSLongTermPlan www.longtermplan.nhs.uk [email protected] www.longtermplan.nhs.uk #NHSLongTermPlan January 2019 The NHS Long Term Plan 3 Contents THE NHS LONG TERM PLAN – OVERVIEW AND SUMMARY 6 CHAPTER 1: A NEW SERVICE MODEL FOR THE 21ST CENTURY 11 1. We will boost ‘out-of-hospital’ care, and finally dissolve the historic divide 13 between primary and community health services A new NHS offer of urgent community response and recovery support 14 Primary care networks of local GP practices and community teams 14 Guaranteed NHS support to people living in care homes 15 Supporting people to age well 16 2. The NHS will reduce pressure on emergency hospital services 18 Pre-hospital urgent care 19 Reforms to hospital emergency care – Same Day Emergency Care 21 Cutting delays in patients being able to go home 23 3. People will get more control over their own health and more personalised 24 care when they need it 4. Digitally-enabled primary and outpatient care will go mainstream 25 across the NHS 5. Local NHS organisations will increasingly focus on population health – 29 moving to Integrated Care Systems everywhere CHAPTER 2: MORE NHS ACTION ON PREVENTION AND HEALTH INEQUALITIES 33 Smoking 34 Obesity 36 Alcohol 38 Air pollution 38 Antimicrobial resistance 39 Stronger NHS action on health inequalities 39 CHAPTER 3: FURTHER PROGRESS ON CARE QUALITY AND OUTCOMES 44 A strong start in life for children and young people 45 Maternity and neonatal services 46 Children -

South Central Strategic Health Authority 2012-13 Annual Report and Accounts

South Central Strategic Health Authority 2012-13 Annual Report and Accounts You may re-use the text of this document (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ © Crown copyright Published to gov.uk, in PDF format only. www.gov.uk/dh 2 South Central Strategic Health Authority 2012-13 Annual Report and Accounts 3 South Central Strategic Health Authority Annual Report 2012/13 The three Strategic Health Authorities (SHAs) in the South of England – South Central, South East Coast and South West – merged to form one SHA for the South of England in October 2011. However, three versions of the annual report have been produced because each individual SHA is a statutory body and therefore required to produce an annual report. Each report should be read in conjunction with the SHA handover documents: ● Maintaining and improving quality during transition: handover document ● Operational Handover and Closedown Report Chairman and Chief Executive’s Foreword This year has been a challenging and busy time for the NHS and the South of England has been no exception. As new NHS structures have emerged, staff have worked hard to set up new systems and develop new working relationships while continuing to deliver the demands of their current roles without interruption. All parts of the NHS across the South of England have worked together to sustain and improve the quality of services delivered and to leave a strong legacy so that all the new Chairman Dr Geoff Harris OBE Clinical Commissioning Groups will start without debt. -

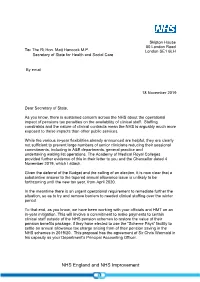

Letter from Simon Stevens to Matt Hancock on 18 November 2019

Skipton House 80 London Road To: The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock M.P. London SE1 6LH Secretary of State for Health and Social Care By email 18 November 2019 Dear Secretary of State, As you know, there is sustained concern across the NHS about the operational impact of pensions tax penalties on the availability of clinical staff. Staffing constraints and the nature of clinical contracts mean the NHS is arguably much more exposed to these impacts than other public services. While the various in-year flexibilities already announced are helpful, they are clearly not sufficient to prevent large numbers of senior clinicians reducing their sessional commitments, including in A&E departments, general practice and undertaking waiting list operations. The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges provided further evidence of this in their letter to you and the Chancellor dated 4 November 2019, which I attach. Given the deferral of the Budget and the calling of an election, it is now clear that a substantive answer to the tapered annual allowance issue is unlikely to be forthcoming until the new tax year, from April 2020. In the meantime there is an urgent operational requirement to remediate further the situation, so as to try and remove barriers to needed clinical staffing over the winter period. To that end, as you know, we have been working with your officials and HMT on an in-year mitigation. This will involve a commitment to make payments to certain clinical staff outside of the NHS pension schemes to restore the value of their pension benefits package, if they have elected to use the “Scheme Pays” facility to settle an annual allowance tax charge arising from of their pension saving in the NHS schemes in 2019/20. -

NHS England Board Members

BOARD OF DIRECTORS - REGISTER OF INTEREST NHS England and NHS Improvement are committed to openness and transparency in its work and decision making. As part of that commitment, we maintain and publish this Register of Interests which draws together Declarations of Interest made by members of the Board of Directors. In addition, at the commencement of each Board meeting, members of the Board are required to declare any interests. NHS England Board Members Lord David Prior Chair Deputy Chairman Lazards Director Genomics England Board Member WWG Advisory Board, University of Warwick Chairman Quality by Randomisation Limited Currently invested in - Mindful Vidya Baccuico Family interest Son is a Junior doctor Niece is a General Practitioner Sir Simon Stevens Chief Executive Non-Executive Director Commonwealth Fund Family interest Spouse is an unpaid member of the Independent Monitoring Board of Feltham Young Offenders Institution David Roberts Vice Chair Chairman Nationwide Building Society Associate Non-Executive NHS Improvement Director Chairman Beazley Furlonge Ltd Chairman Beazley Plc Non-Executive Director Campion Wilcocks Ltd Member, Strategy Board Henley Business School, University of Reading Advisory Board Member The Mentoring Foundation Daughter Junior Doctor Sister-in-law Salaried GP in Liverpool Niece Senior Midwife in Leeds Niece Senior Nurse in Manchester Niece Works in CCG in Leeds Cousin Works in CCG in Cheshire Chairman Beazley Furlonge Ltd Chairman Beazley Plc Non-Executive Director Campion Wilcocks Ltd Member, Strategy -

The Healthy NHS Board Principles for Good Governance

The Healthy NHS Board Principles for Good Governance Foreword The Healthy NHS Board We are delighted to introduce The Healthy NHS Board: principles for good governance, and would like to encourage boards across the system to make use of this guide as they seek to address the challenges of improving quality for patients. The National Leadership Council (NLC) has led this work to bring the latest research, evidence and thinking together. High Quality Care For All made it clear what the NHS is here to do – to improve the health of our population and to make quality the organising principle of the service. Boards must put quality at the heart of all they do. This guide, and the online resources that accompany it, support boards in exercising that responsibility. When we talk about quality, we mean patient safety, effectiveness of care and patient experience. Assuring these three elements of quality for patients should be central to the work of everyone in the NHS. The NHS is putting in place levers and incentives to improve quality, including linking the payment system more closely with patients’ experiences, as well as strengthening the regulatory system to safeguard quality and safety. As these changes take shape, it is timely to refresh guidance to NHS boards to support them as they go forward. In a system as large and complex as the NHS, it is helpful to have a common understanding of what we mean by good governance and what it takes to be a high-performing board. The NHS has had a decade of growth but is facing the challenge of managing with less in the future. -

Title: Assessing Proposals for a New NHS Structure in England After the Pandemic

1 Title: Assessing proposals for a new NHS structure in England after the pandemic 2 Authors: 3 Hugh Alderwick, head of policy1 4 Phoebe Dunn, research fellow1 5 Tim Gardner, senior fellow1 6 Nicholas Mays, professor of health policy2 7 Jennifer Dixon, chief executive1 8 1 Health Foundation, London, UK 9 2 London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK 10 Correspondence to: 11 Hugh Alderwick; Health Foundation, 8 Salisbury Square, London, EC4Y 8AP; 12 [email protected]; 020 7664 2083 13 Word count: 2153 14 References: 52 15 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 16 Key messages: 17 - NHS leaders in England are calling for changes to health care system structures and legislation 18 - The changes are designed to support collaboration between organizations and services—and 19 could mean some NHS agencies being abolished and new area-based authorities created 20 - Encouraging collaboration to improve population health makes sense, but the potential benefits of 21 the new system proposed may be overstated and the risks of reorganization underplayed 22 - NHS leaders and government have a long list of policy priorities as the country recovers from the 23 pandemic. A major structural reorganization of the health care system should not be one of them 24 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 25 Contributors and sources: All authors are researchers in health policy and public health in the UK 26 and have experience analysing health care system reforms in England and elsewhere. All authors 27 contributed to the intellectual content. HA and PD wrote the first draft of the article. PD, JD, TG and 28 NM commented and made revisions. -

Will a New NHS Structure in England Help

ANALYSIS BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.n248 on 3 February 2021. Downloaded from 1 Health Foundation, London, UK Will a new NHS structure in England help recovery from the pandemic? 2 London School of Hygiene and The health policy challenges facing the NHS and government are enormous, but Hugh Alderwick Tropical Medicine, London, UK and colleagues argue that a major reorganisation is not the solution Correspondence to: H Alderwick [email protected] Hugh Alderwick, 1 Phoebe Dunn, 1 Tim Gardner, 1 Nicholas Mays, 2 Jennifer Dixon1 Cite this as: BMJ 2021;372:n248 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n248 The NHS has just faced the most difficult year in its Proposals included removing requirements to Published: 03 February 2021 history. The arrival of covid-19 vaccines provides competitively tender some NHS services, and hope that the UK may bring the pandemic under establishing local partnership committees with control in 2021, but the NHS will feel the effects of powers to make decisions on local priorities and covid-19 for many years. Serious short term spending. The proposals were designed to avoid a challenges also remain: hospitals are under extreme major reorganisation but risked replacing one set of strain,1 the backlog of unmet healthcare needs is workarounds with another.9 The plans were shelved substantial,2 and the NHS faces the mammoth task when covid-19 hit, but now legislation is back on the of vaccinating the population against covid-19.3 agenda10 and NHS England has published expanded proposals for changes to the NHS after the pandemic. -

TRUST BOARD1 Thursday, 30 January 2014 1500 Sir William Well’S Atrium, Royal Free Hospital, Ground Floor Dominic Dodd, Chairman ITEM LEAD PAPER 1

TRUST BOARD1 Thursday, 30 January 2014 1500 Sir William Well’s Atrium, Royal Free Hospital, ground floor Dominic Dodd, Chairman ITEM LEAD PAPER 1. ADMINISTRATIVE ITEMS 1.1 Apologies for absence ‐ D Dodd, S Payne 1.2 Minutes of meeting held 24 October 2013 D Bernstein 1.1 1.3 Matters arising report D Bernstein 1.2 1.4 Record of items discussed at Part II board meetings on 24 October, 28 D Bernstein 1.3 November, 19 December 2013 and 8 January 2014 1.5 Patient voices D Oakley v 2. ORGANISATIONAL AGENDA 2.1 Nurse staffing on wards (Francis report) D Sanders 2.1 2.2 Declaration of compliance – mixed sex wards D Sanders 2.2 2.3 DIPC report D Sanders 2.3 2.4 Annual equality information report D Sanders 2.4 2.5 Quarterly medical revalidation report S Powis 2.5 2.6 Quality accounts 2013/14 – development timetable and sign off process S Powis 2.6 3. OPERATIONAL AGENDA 3.1 Chairman’s report D Bernstein 3.1 3.2 Chief executive’s report D Sloman 3.2 3.3 Trust performance report D Sloman 3.3 3.4 Financial performance report C Clarke 3.4 Governance and Regulation: reports from board committees 3.5 Finance and performance committee report D Bernstein 3.5 3.6 Strategy and investment committee report D Bernstein 3.6 3.7 Risk, governance and regulation committee report S Ainger 3.7 3.8 Audit committee report D Oakley 3.8 3.9 Clinical performance committee report A Schapira 3.9 3.10 User experience committee report J Owen 3.10 4.