Pathological Hoarding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Compulsive Hoarding

UNDERSTANDING COMPULSIVE HOARDING "The general public thinks these people are just slobs or lazy, but actually most of the time it's because of not wanting to waste things, and so wanting to make the right decision about a thing that it becomes overwhelming and they keep it." Jason Elias», OCD Institute at Harvard's McLean Hospital OCD Research Program Categorizing, staying focused and decision-making are extremely difficult for those who hoard. Perfectionism» is a component as well: By saving possessions, the compulsive hoarder postpones making the decision to discard something and, therefore, avoids experiencing anxiety about making a mistake or being less than perfectly prepared. The most commonly saved items include newspapers, magazines, old clothing, bags, books, mail, notes, and lists. (Frost & Gross, 1993; Winsberg et al., 1999). Read Introduction to Hoarding.(pdf) Read Hoarding 101.(pdf) Read Hoarding from the Inside Out.(pdf) Read How & When to Intervene (pdf) What IS Compulsive Hoarding? Hoarding is defined as the acquisition of, and inability to discard worthless items even though they appear (to others) to have no value. Hoarding behaviors can occur in a variety of psychiatric disorders and in the normal population, but are most commonly found in people with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Those people who report compulsive hoarding as their primary type of OCD, experience significant distress or functional impairment from their hoarding. They have symptoms of indecisiveness, procrastination, and avoidance, are classified as having compulsive hoarding syndrome. An estimated 700,000 to 1.4 million people in the United States are believed to have compulsive hoarding syndrome. -

Diogenes Syndrome: Patients Living with Hoarding and Squalor

Case notes z Diogenes syndrome Diogenes syndrome: patients living with hoarding and squalor Debbie Browne MBChB, MRCPsych, Rekha Hegde MBChB, MRCPsych With a growing awareness that hoarding can be found in many psychiatric conditions, clinicians may recognise an increase in referrals for people presenting with hoarding. Here, the authors present three cases of hoarding behaviour stemming from different psychiatric conditions and discuss how hoarding can be managed. oarding down, or senile squalor syndrome disorders ,paraphrenia 8and subtle Hhas cap - 6 and it can be understood as: frontal lobe deficits not fulfilling tured the pub - • Acquisition of, and inability to diagnostic criteria for dementia . lic imagination discard, objects that to others have in recent years, (seemingly) little value – hoarding Background with television (syllogomania) Macmillan & Shaw (1966) studied programmes • Self neglect a population of individuals living such as Channel 4’s ‘The Hoarder • Environmental neglect (squalor) in squalor and described the con - Next Door’ 1 or TLC’s ‘Hoarding: • With refusal of help / isolation dition as a ‘senile breakdown’ of Buried Alive’. 2 The terms hoard - • Seeming lack of concern by the the standards of hygiene accepted ing and Diogenes are sometimes person with regards to their by the local community. More than used interchangeably but it is more situation. half of the sample was found to useful to think of Diogenes as have a psychiatric disorder and an hoarding with self and environ - Epidemiology equal proportion presented hoard - mental neglect, ie squalor. The accepted incidence of ing personality traits. 10 With changes in legislation Diogenes syndrome is 0.5 per 1000 Karl Jaspers called it the social (such as the Mental Capacity Act over the age of 65 years. -

Cross-Disorder Genetic Analysis of Tic Disorders, Obsessive–Compulsive, and Hoarding Symptoms

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Frontiers - Publisher Connector ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 30 June 2016 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00120 Cross-Disorder Genetic Analysis of Tic Disorders, Obsessive–Compulsive, and Hoarding Symptoms Nuno R. Zilhão1,2*, Dirk J. Smit2,3, Dorret I. Boomsma2 and Danielle C. Cath1,4 1 Department of Clinical and Health Psychology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands, 2 Department of Biological Psychology, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 3 Neuroscience Campus Amsterdam, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 4 Altrecht Academic Anxiety Center, Utrecht, Netherlands Hoarding, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), and Tourette’s disorder (TD) are psychiatric disorders that share symptom overlap, which might partly be the result of shared genetic variation. Population-based twin studies have found significant genetic correlations between hoarding and OCD symptoms, with genetic correlations varying between 0.1 and 0.45. For tic disorders, studies examining these correlations are lack- ing. Other lines of research, including clinical samples and GWAS or CNV data to explore genetic relationships between tic disorders and OCD, have only found very modest if Edited by: any shared genetic variation. Our aim was to extend current knowledge on the genetic Peristera Paschou, structure underlying hoarding, OC symptoms (OCS), and lifetime tic symptoms and, in a Democritus University trivariate analysis, assess the degree of common and unique genetic factors contributing of Thrace, Greece to the etiology of these disorders. Data have been gathered from participants in the Reviewed by: Biju Viswanath, Netherlands Twin Register comprising a total of 5293 individuals from a sample of adult National Institute of Mental Health monozygotic (n = 2460) and dizygotic (n = 2833) twin pairs (mean age 33.61 years). -

What Are Effective Interventions for Hoarding?

Rapid Review What are effective interventions for hoarding? What you need to know Little research exists on the efficacy of interventions specifically designed to treat hoarding disorder, but a number of approaches are demonstrating successful outcomes. Many jurisdictions have formed community hoarding taskforces made up of professionals from a broad range of disciplines and are showing particularly promising results. A form of cognitive behavioural therapy designed specifically to treat hoarding has proven effective, and adapted versions are being tested for use with specific populations, in groups, in home settings, and via the web, as well as for use with other forms of treatment. Approaches must take into account that many individuals who hoard are resistant to assessment and treatment. The complex nature of hoarding disorder calls for dynamic treatment approaches, with the precise services required being determined on a case-by-case basis. What’s the problem? Hoarding is not a new phenomenon; however, it has only recently been classified as a distinct mental disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V, 2013). Hoarding disorder (HD) is characterized by the excessive accumulation of items and a refusal to discard these items, resulting in significant impairment.10 Recent estimates suggest that 2% to 5% of the adult population engage in some type of hoarding behaviour,10, 12 which can create hazardous living conditions for individuals and communities.11 1 www.eenet.ca Rapid Review With awareness of hoarding on the rise, the prevalence of self-reporting and referrals from service providers is also increasing.11, 16 As a result, health practitioners and researchers are focusing on how to treat and remedy the often debilitating symptoms. -

Hoarding Disorder Basics & Treatments

Hoarding Disorder Basics, Treatments & Goals & Purposes for the Southwestern Vermont Hoarding Task Force in Rutland County Kate E. Tibbs Program Specialist for the Southwestern Vermont Hoarding Task Force [email protected] (802)665-1705 “Hanging on prevents people from converting their deeper emotional ambivalences into “the ambiguity of love and hate”—the creative holding on to two feelings at once.” -from Mess: One Man’s Struggle to Clean Up His House & His Act by Yourgrau, 2015 2 “…hoarding represents a paradox of opportunity. Hoarders are gifted with the ability to see opportunities in so many things. They are equally cursed with the inability to let go of any of these possibilities...” -from Stuff by Frost and Steketee, 2010 3 Basics about hoarding / hoarding disorder What is hoarding? • Included in DSM-5 as an official disorder • Difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of the value • Causes significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning • Difficulty maintaining an environment for self and/or others (including animals) Photo taken by BROC Weatherization team • Causes people to feel isolated, puts strain on relationships and/or difficulty developing relationships • Excessive clutter in the home to the point where it becomes unsafe & unhealthy for everyone (pets, too!) in the home 4 Basics about hoarding / hoarding disorder continued Affects approximately 2-5% of the population; more recent studies have calculated 5% or 1 in 20 people Compulsive hoarding • Attempting to decrease stress & anxiety Quantity of their collected items sets them apart from people with normal collecting behaviors • Excessive shopping, collecting trash, bargain shopping Rooms in the home are not used for their intentional purposes Most commonly hoarded items: • Papers, books, clothes, food, furniture, etc. -

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder I have no financial relationships to disclose. History • OCD had historically been felt to be the quintessential psychodynamic illness • The PANDAS studies have cast doubt on this • Researchers feel that obsessive compulsive disorder can be ther result of an autoimmune inflammation of the CSTC (cortical-striatal- thalamic-cortical ) circuit in the brain. It is now listed as a poststreptococcal infection sequelae. OCD • This finding strengthens the link between traditional psychiaatry and neurology. • It points to the idea that for anything a human being experiencesm, there must be a neural corelate. • Therefore, the understanding of neuroanatomy and neurophysioogy is very important. Link Between Psychiatry and Neurology • The PANDAS • Pediaatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders • Associated with • Streptococcal infection CSTC Circuit Symptoms of OCD • Recurrent thoughts, urges, and images that are intrusive and unwanted causing anxiety. • Behaavioral or mental acts that are aimed at preventing or reducing anxiety, distress, or some dreadful event or situation Symptomatic Concerns • Aggression • Contamination • Pathologic doubt • Religious scrupulosity • Sexuality • Superstition • Symmetry and exactness Onset • Typical age of onset is between 19 and 25 years • It can certainly begin at a younger age\ • De novo ocd in geriatrics is unusual; an exception to this is the distinct subgroup of patients with compulsive hoarding symptoms, a syndrome often comorbid with OCD. • Many patients with OCD do not seek -

Personality, Mental Health and Demographic Correlates of Hoarding Behaviours in a Midlife Sample

Personality, mental health and demographic correlates of hoarding behaviours in a midlife sample Janet K. Spittlehouse1, Esther Vierck1, John F. Pearson2 and Peter R. Joyce1 1 Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Otago, Christchurch, Christchurch, New Zealand 2 Biostatistics and Computational Biology Unit, University of Otago, Christchurch, Christchurch, New Zealand ABSTRACT We describe the Temperament and Character Inventory personality traits, demographic features, physical and mental health variables associated with hoarding behaviour in a random community sample of midlife participants in New Zealand. A sample of 404 midlife participants was recruited to a study of ageing. To assess hoarding behaviours participants completed the Savings Inventory-Revised (SI-R), personality was assessed by the Temperament and Character Inventory and self-reported health was measured by the Short Form-36v2 (SF-36v2). Other measures were used to assess socio-demographic variables and current mental disorders. Participants were split into four groups by SI-R total score (scores: 0–4, 5–30, 31–41 and >41). Those who scored >41 on the SI-R were classified as having pathological hoarding. Trend tests were calculated across the four hoarding groups for socio-demographic, personality, mental and physical health variables. SI-R scores ranged from 0 to 58. The prevalence of pathological hoarding was 2.5% and a further 4% reported sub-clinical symptoms of hoarding. Higher hoarding behaviour scores were related to higher Temperament and Character Inventory scores for Harm Avoidance and lower scores for Self-directedness. Persistence and Cooperativeness scores were lower too but to a lesser extent. Trend analysis revealed that those with higher hoarding behaviour scores were more likely to be single, female, unemployed, receive income support, have a lower socio-economic status, lower household income and have poorer self-reported mental health scores. -

Hoarding in Children and Adolescents with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: Prevalence, Clinical Correlates, and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Outcome

European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2019) 28:1097–1106 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01276-x ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Hoarding in children and adolescents with obsessive–compulsive disorder: prevalence, clinical correlates, and cognitive behavioral therapy outcome Davíð R. M. A. Højgaard1 · Gudmundur Skarphedinsson2 · Tord Ivarsson3 · Bernhard Weidle4 · Judith Becker Nissen1 · Katja A. Hybel1 · Nor Christian Torp5 · Karin Melin6 · Per Hove Thomsen1,4 Received: 4 May 2018 / Accepted: 7 January 2019 / Published online: 17 January 2019 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Hoarding, common in pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), has specifc clinical correlates and is associated with poor prognosis. However, there are few studies of hoarding in pediatric OCD. This study estimates the occurrence of hoarding symptoms in a sample of children and adolescents with OCD, investigating possible diferences in demographic and clinical variables between pediatric OCD with and without hoarding symptoms. Furthermore, the study investigates whether hoarding symptoms predict poorer treatment outcomes after cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The study sample comprised 269 children and adolescents with OCD, aged 7–17 years, from Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, who were all included in the Nordic long-term obsessive–compulsive disorder Treatment Study. All had an OCD diagnosis according to the DSM-IV and were treated with 14 weekly sessions of manualized, exposure-based CBT. Hoarding symptoms and OCD severity were assessed with the Children’s Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale and group diferences in treatment outcome were analyzed using linear mixed-efect modelling. Seventy-two patients (26.8%) had one or more symptoms of hoarding. Comorbid tic disorders (p = 0.005) and indecision (p = 0.024) were more prevalent among those with hoarding symptoms than those without hoarding symptoms. -

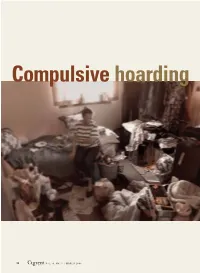

Compulsive Hoarding

Compulsive hoarding 12 Current VOL. 4, NO. 3 / MARCH 2005 p SYCHIATRY Current p SYCHIATRY Unclutter lives and homes by breaking anxiety’s grip Fear about making ‘wrong’ decisions ompulsive hoarding behavior is considered notoriously difficult to may underlie hoarders’ pathologic Ctreat, but targeting its characteristic symptoms saving and collecting behaviors. with medication and psychotherapy can be suc- cessful. This article provides a guide for the psy- Here’s a strategy to help them chiatrist—alone or with a cognitive-behavioral therapist—to diagnose compulsive hoarding syn- drome and help patients overcome the anxieties Jamie Feusner, MD that fuel its symptoms. Psychobiology research fellow and staff psychiatrist OCD Intensive Treatment Program Anxiety Disorders Clinic WHAT IS COMPULSIVE HOARDING? Hoarders acquire and are unable to discard items Sanjaya Saxena, MD that others consider of little use or value.1 They Associate professor in residence and director, most often save newspapers, magazines, old cloth- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Research Program Associate director, Anxiety Disorders Program ing, bags, books, mail, notes, and lists. Hoarding and saving behaviors occur in nonclinical popula- Department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences tions and with other neuropsychiatric disorders— David Geffen School of Medicine schizophrenia, dementia, eating disorders, mental University of California, Los Angeles retardation—but are most often found in persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). OCD is a heterogeneous clinical entity with several major symptom domains:2,3 • aggressive, sexual, and religious obsessions with checking compulsions © Scott Eklund/Seattle Post-Intelligencer VOL. 4, NO. 3 / MARCH 2005 13 Hoarding • symmetry/order obsessions with Box ordering, arranging, and repeating What causes compulsive hoarding? compulsions Genetics. -

Hoarding Disorder: Mental Health and Public Safety

+ Hoarding Disorder: Mental Health and Public Safety Janet Yeats, MA LMFT, Co-founder, The Hoarding Project MN Coalition for the Homeless – 9.15.14 www.thehoardingproject.org + Objectives n Recognize effective diagnosis and treatment strategies of hoarding disorder. n Describe alternative options to treatment other than a forced cleanout. n Apply evidence-based treatment strategies to address issues of safety in hoarding disorder. n Develop collaborative networks in your area to form a community response to hoarding disorder. + Who We Are n 501(c)(3) public charity n Mission: To promote an effective, ethical, and sustainable response to hoarding in communities, through research, education and prevention, and collaborative approaches to treatment. Background on +Hoarding Disorder: Inside the Mind of a Person Who Hoards + What is hoarding disorder? Quick answer: With the DSM5 hoarding disorder is a diagnosis, the common definition has 4 parts: 1. Excessive acquisition of stuff* 2. Difficulty discarding possessions 3. Living spaces that can’t be used for their intended purposes because of clutter 4. Causing significant distress or impairment (Frost & Hartl, 1996 ) *Not universal in all people who hoard + How many people hoard and are some people more likely to hoard than others? Research shows that n About 2-5% of the population hoard, which is about 15 million people in the U.S., on the high end (Iervolino et al., 2009; Samuels et al., 2008) n Likely this number is small – qualitative experience says 20-25%. n Older people hoard more than younger people n People with lower income hoard more than people with higher income (Samuels, et al. -

Diagnostic Criteria Associated with a Cohort of Children Identified with Symptoms of Postinfectious Autoimmune Encephalopathy A

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA ASSOCIATED WITH A COHORT OF CHILDREN IDENTIFIED WITH SYMPTOMS OF POSTINFECTIOUS AUTOIMMUNE ENCEPHALOPATHY A Scholarly Project submitted to the faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Nursing Practice By Tara Fox, M.S.N. Washington, DC March 31, 2020 Copyright by 2020 by Tara R. Fox All Rights Reserved ii DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA ASSOCIATED WITH A COHORT OF CHILDREN IDENTIFIED WITH SYMPTOMS OF POSTINFECTIOUS AUTOIMMUNE ENCEPHALOPATHY (PAE) Tara R. Fox, M.S.N Thesis Advisor: Jean Farley, D.N.P. and Margaret Slota, D.N.P. ABSTRACT Postinfectious Autoimmune Encephalopathy (PAE) is well defined in the literature; however, a provider may be unaware of its existence or have a difficult time distinguishing the disorder from other neuropsychiatric conditions, such as OCD and anxiety (Leon, et. al, 2018). Availability of a valid and reliable screening tool would contribute to improved accuracy in the secondary prevention of PAE. (Helm & Blackwood, 2015). The primary purpose of this project is to determine the frequency that patients clinically identified as having PAE present with diagnostic criteria described in the literature to begin the first step developing such a tool. PAE is a condition in which an infection triggers an autoimmune reaction that targets the nervous system, leading to changes in neurologic function, mood and behavior. PAE includes disorders such as PANDAS, PANS, CANS, PiTANDS, and Sydenham Chorea (Pruss, 2017), and has been recognized as a diagnostic entity since 1995 (Swedo et al., 1998). A strategic search was done at a university library utilizing web-based search engines. -

Compulsive Hoarding Syndrome: Clinical Aspects and Thera- Peutic Implications for Nursing Practice in Community

ΠΕΡΙΕΓΧΕΙΡΗΤΙΚΗ ΝΟΣΗΛΕΥΤΙΚΗ (2019),ΤΟΜΟΣ 8,ΤΕΥΧΟΣ 3 ΑΝΑΣΚΟΠΙΚΗ ΕΡΓΑΣΊΑ COMPULSIVE HOARDING SYNDROME: CLINICAL ASPECTS AND THERA- PEUTIC IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING PRACTICE IN COMMUNITY Afroditi Zartaloudi Lecturer, Department of Nursing, University of West Attica, Athens DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3631122 Cite as: Zartaloudi,Afroditi. (2020). Compulsive hoarding syndrome: clinical aspects and ther-apeutic implications for nursing prac- tice in community. Perioperative Nursing (GORNA), E-ISSN:2241-3634, 8(3), 180–192. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3631122 AbstraCt ThE aim of the present study was to provide an overview of the compulsive hoarding syndrome, including manifesta- tions of the problem, comorbidity and diagnostic issues, treatment approaches, epidemiology, course, and demo- graphic features of compulsive hoarding. Material and MEthod: A literature review was conducted on both Greek and English languages, through Pubmed, Scopus, Science Direct and Google Scholar databases, using the key-words: "com- pulsive hoarding", "treatment" "community". Results: Compulsive hoarding is a disabling psychological disorder char- acterized by acquisition, clutter, excessive collection of items, and inability to discard. Associated with increased risk of injury due to the severe clutter and unsanitary conditions, social isolation and disorganization, compulsive hoarding can be devastating for individuals, family members, and communities. Treatment may be affected by the accuracy of the community nurse’s understanding of this complex disorder and educating individual hoarders, family and commu- nity members and other health care professionals as the effects of hoarding often extend outside the home. ConClu- sions: Compulsive hoarding is a serious public health problem that poses significant health and safety risks for individ- uals, families, and communities and has a profound effect on public health in terms of poor physical health, occupa- tional impairment, and health care service involvement.