19-Verrier Cartoons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martinrowson.Pdf

Martin Rowson on Free Speech and Cartoons Nigel Warburton: Martin Rowson is a satirical cartoonist. I asked him about free speech, cartoons, and causing offence. Don’t listen to this podcast if you are offended by swearing. Nigel Warburton: Michael Rowson, welcome to Free Speech Bites. Michael Rowson: Hello. Nigel Warburton: The topic we're going to focus on is free speech and cartoons. I wonder if you could begin by saying something about your own work as a cartoonist. Michael Rowson: I suppose I have a bit of a reputation for being one of the more hard- hitting Lefty cartoonists, and I'm very fortunate - this isn't just brown-nosing - to work for the Guardian who tolerate that kind of thing from me and Steve Bell, although sometimes I think they don't notice until it's too late. I see myself, very proudly actually, as part of a uniquely British tradition. We are, as a country, the only country in the world that has had over 300 years of tolerated visual satire, which hasn't been subjected to the kind of constraints it has in other countries around the world, which is why, since the advent of the Internet, when Steve and I have had our work available to a global audience, we have had such visceral responses from people who are just not used to this kind of thing. As soon as they started putting our work on the Guardian website and the Guardian website took off in America, the traffic of hate mail, hate email, from America, was quite extraordinary, quite deliberately targeted. -

The First Amendment, the Public-Private Distinction, and Nongovernmental Suppression of Wartime Political Debate Gregory P

Working Paper Series Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Year 2004 The First Amendment, The Public-Private Distinction, and Nongovernmental Suppression of Wartime Political Debate Gregory P. Magarian Villanova University School of Law, [email protected] This paper is posted at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. http://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/wps/art6 THE FIRST AMENDMENT, THE PUBLIC -PRIVA TE DISTINCTION, AND NONGOVERNMENTAL SUPPRESSION OF WARTIME POLITICAL DEBATE 1 BY GREGORY P. MAGARIAN DRAFT 5-12-04 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 1 I. CONFRONTING NONGOVERNMENTAL CENSORSHIP OF POLITICAL DEBATE IN WARTIME .................. 5 A. The Value and Vulnerability of Wartime Political Debate ........................................................................... 5 1. The Historical Vulnerability of Wartime Political Debate to Nongovernmental Suppression ....................................................................... 5 2. The Public Rights Theory of Expressive Freedom and the Necessity of Robust Political Debate for Democratic Self -Government........................ 11 B. Nongovernmental Censorship of Political Speech During the “War on Terrorism” ............................................... 18 1. Misinformation and Suppression of Information by News Media ............................................ 19 2. Exclusions of Political Speakers from Privately Owned Public Spaces. -

What Inflamed the Iraq War?

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Fellowship Paper, University of Oxford What Inflamed The Iraq War? The Perspectives of American Cartoonists By Rania M.R. Saleh Hilary Term 2008 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my deepest appreciation to the Heikal Foundation for Arab Journalism, particularly to its founder, Mr. Mohamed Hassanein Heikal. His support and encouragement made this study come true. Also, special thanks go to Hani Shukrallah, executive director, and Nora Koloyan, for their time and patience. I would like also to give my sincere thanks to Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, particularly to its director Dr Sarmila Bose. My warm gratitude goes to Trevor Mostyn, senior advisor, for his time and for his generous help and encouragement, and to Reuter's administrators, Kate and Tori. Special acknowledgement goes to my academic supervisor, Dr. Eduardo Posada Carbo for his general guidance and helpful suggestions and to my specialist supervisor, Dr. Walter Armbrust, for his valuable advice and information. I would like also to thank Professor Avi Shlaim, for his articles on the Middle East and for his concern. Special thanks go to the staff members of the Middle East Center for hosting our (Heikal fellows) final presentation and for their fruitful feedback. My sincere appreciation and gratitude go to my mother for her continuous support, understanding and encouragement, and to all my friends, particularly, Amina Zaghloul and Amr Okasha for telling me about this fellowship program and for their support. Many thanks are to John Kelley for sharing with me information and thoughts on American newspapers with more focus on the Washington Post . -

Journal of Visual Culture

Journal of Visual Culture http://vcu.sagepub.com/ Just Joking? Chimps, Obama and Racial Stereotype Dora Apel Journal of Visual Culture 2009 8: 134 DOI: 10.1177/14704129090080020203 The online version of this article can be found at: http://vcu.sagepub.com/content/8/2/134 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Journal of Visual Culture can be found at: Email Alerts: http://vcu.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://vcu.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://vcu.sagepub.com/content/8/2/134.refs.html >> Version of Record - Nov 20, 2009 What is This? Downloaded from vcu.sagepub.com at WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY on October 8, 2014 134 journal of visual culture 8(2) Just Joking? Chimps, Obama and Racial Stereotype We are decidedly not in a ‘post-racial’ America, whatever that may look like; indeed, many have been made more uneasy by the election of a black president and the accompanying euphoria, evoking a concomitant racial backlash in the form of allegedly satirical visual imagery. Such imagery attempts to dispel anxieties about race and ‘blackness’ by reifying the old racial stereotypes that suggest African Americans are really culturally and intellectually inferior and therefore not to be feared, that the threat of blackness can be neutralized or subverted through caricature and mockery. When the perpetrators and promulgators of such imagery are caught in the light of national media and accused of racial bias, whether blatant or implied, they always resort to the same ideological escape hatch: it was only ‘a joke’. -

Summer Catalog 2020

5)&5*/:#00,4503& Summer Catalog 2020 Summer books for readers of all ages Arts and Crafts……………………………………………………………. p.1 Biography and Autobiography………………………………...……. p. 1-2 Business and Economics……………………………………...……….. p. 2-4 Comics and Graphic Novels……………………………..…………… p. 4-6 Computers and Gaming………………………………...…….……….. p. 6 Cooking……………………………………………………………………… p. 6 Education…………………………………………………………………… p. 6 Family and Relationships………………………………...……………. p. 6 Adult Fiction………………………………………………….……………. p. 7-10 Health and Fitness…………………………………………..…………… p. 10 History……………………………………………………………………….. p. 10 Humor…………………………………………………………….………….. p. 11 Kids Fiction for Kids…………………………………………………… p. 11-18 Nonfiction for Kids……………………………………………… p. 18-20 Social Studies Language Arts………………………………………...........…….. p. 21 Law………………………………………………………….….....….. p. 21 Literary Collections……………………………………..…........ p. 21 Math…………………………………………………………..…....... p. 21 Philosophy…………………………………………………..…...... p. 21 Table of Contents of Table Politics…………………………………………………………........ p. 21-22 Psychology…………………………………………………......…. p. 23 Religion……………………………………....…………………..… p. 23 Science………………………………………....…………………... p. 23 Self-Help……………………………………………….………………....... p. 23-25 Social Science…………………………………………………………….. p. 25 Sports………………………………………………………………………… p. 25 True Crime…………………………………………………………………. p. 25 Young Adult Fiction……………………………………………………................ p. 25-27 Nonfiction……………………………………………................… p. 27-28 Buy Online and Pick-up at Store or Shop and Ship to Home tinybookspgh.com/online -

Adam Dant 'The Government Stable'

ADAM DANT ‘THE GOVERNMENT STABLE’ 2015 GENERAL ELECTION ARTWORK – A KEY TO THE DRAWING ADAM DANT ‘THE GOVERNMENT STABLE’ 2015 GENERAL ELECTION ARTWORK Places: 1. Leeds Town Hall: The Victorian Civic architectural splendor of Leeds Town Hall was the venue for the BBC’s final leadership orations. The ceiling and arches are decorated with the logos of the UK political parties. 2. Central Methodist Hall, Westminster: The clock and pipe organ are from the Central Methodist Hall where the BBC’s ‘Challengers’ Debate’ took place. At 10pm the clock marks the time that polling stations across the UK closed and voting ended. 3. Swindon University Technical College Water Tower and Courtyard Pavement: Venue for The Conservative Party Manifesto Launch; the college occupies Swindon’s former Railway Village. 4. Testbed 1 Nightclub Battersea: Hanging from the ceiling are glow-stick lights from the trendy, power-cut-hit, Liberal Democrat Manifesto launch venue. Panels on the ceiling are decorated with the Lib Dem’s backdrop of children’s hand prints. 5. Arcellor Mittal Tower, Queen Elizabeth ll Olympic Park: The Labour Party Election Campaign launch took place in the viewing gallery of the Mittal tower. The party leader was introduced by an NHS nurse entering through a receiving line of cheering Labour Student activists. 6. Escalators from UKIP’s poster on immigration policy. 7. Rahere Climbing Centre, Edinburgh: Vertiginous, hand hold studded climbing walls provided the backdrop to the Scottish National party Manifesto launch. 8. The White Cliffs of Dover: The United Kingdom Independence Party unveiled a campaign poster depicting three escalators traveling up the White Cliffs of Dover at The Coastguard Inn, St Margaret’s with the cliffs the English Channel and France Telecom on everyone’s mobile phones as a backdrop. -

PSA Awards 2005

POLITICAL STUDIES ASSOCIATION AWARDS 2005 29 NOVEMBER 2005 Institute of Directors, 116 Pall Mall, London SW1Y 5ED Political Studies Association Awards 2005 Sponsors The Political Studies Association wishes to thank the sponsors of the 2005 Awards: Awards Judges Event Organisers Published in 2005 by Edited by Professor John Benyon Political Studies Association: Political Studies Association Professor Jonathan Tonge Professor Neil Collins Jack Arthurs Department of Politics Dr Catherine McGlynn Dr Catherine Fieschi Professor John Benyon University of Newcastle Professor John Benyon Professor Charlie Jeffery Dr Justin Fisher Newcastle upon Tyne Jack Arthurs Professor Wyn Grant Professor Ivor Gaber NE1 7RU Professor Joni Lovenduski Professor Jonathan Tonge Designed by Professor Lord Parekh Tel: 0191 222 8021 www.infinitedesign.com Professor William Paterson Neil Stewart Associates: Fax: 0191 222 3499 Peter Riddell Eileen Ashbrook e-mail: [email protected] Printed by Neil Stewart Yvonne Le Roux Potts Printers Liz Parkin www.psa.ac.uk Miriam Sigler Marjorie Thompson Copyright © Political Studies Association. All rights reserved Registered Charity no. 1071825 Company limited by guarantee in England and Wales no. 3628986 A W ARDS • 2004 Welcome I am delighted to welcome you to the Political Studies Association 2005 Awards. This event offers a rare opportunity to celebrate the work of academics, politicians and journalists. The health of our democracy requires that persons of high calibre enter public life. Today we celebrate the contributions made by several elected parliamentarians of distinction. Equally, governments rely upon objective and analytical research offered by academics. Today’s event recognizes the substantial contributions made by several intellectuals who have devoted their careers to the conduct of independent and impartial study. -

THE NEWZOOM Does Journalism Need Offices? Contents

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | OCTOBER-NOVEMBER 2020 THE NEWZOOM Does journalism need offices? Contents Main feature 12 News from the home front Is the end of the office nigh? News he coronavirus pandemic is changing 03 Thousands of job cuts take effect the way we live and work radically. Not least among the changes is our Union negotiates redundancies widespread working from home and 04 Fury over News UK contracts the broader question of how much we Photographers lose rights Tneed an office. Some businesses are questioning whether they need one at all, others are looking 05 Bullivant strike saves jobs towards a future of mixed working patterns with some Management enters into talks homeworking and some office attendance. In our cover feature 06 TUC Congress Neil Merrick looks at what this means for our industry. Reports from first virtual meeting Also in this edition of The Journalist we have a feature on how virtual meetings are generating more activity in branches “because the meetings are now more accessible. Edinburgh Features Freelance branch has seen a big jump in people getting 10 Behind closed doors involved, has increased the frequency of its meetings and has Reporting the family courts linked up with other branches for joint meetings. Recently, the TUC held its first virtual conference. We have full 14 News takes centre stage coverage of the main issues and those raised by the NUJ. Media takes to innovative story telling As we work from home there’s growing evidence of a revival 21 Saving my A&E in the local economy and a strengthening of the high street A sharp PR learning curve which not that long ago was suffering as consumers opted for large out of town centres. -

Complaint by Mr Christopher Williams About Going Underground Lockdown Edition

v Issue 425 26 April 2021 Complaint by Mr Christopher Williams about Going Underground Lockdown Edition Type of case Fairness and Privacy Outcome Not Upheld Service RT Date & time 29 July 2020, 09:30 Category Fairness Summary Ofcom has not upheld this complaint about unjust or unfair treatment in the programme as broadcast. Case summary The programme was a discussion and phone-in programme concerning topical issues. During the programme, the presenter interviewed Mr Steve Bell, a political cartoonist for The Guardian newspaper about reports that he had been fired from the publication. Mr Williams complained of unjust or unfair treatment in the programme because it included “false claims of inaccuracy in my reporting” which he said were “damaging to my reputation”. Ofcom found that the programme did not present, disregard or omit material facts in a way that was unjust or unfair to Mr Williams, that he was provided an appropriate and timely opportunity to respond and his response was fairly reflected in the programme. Programme summary On 29 July 2020, RT broadcast an edition of Going Underground Lockdown Edition, a discussion and phone-in programme concerning topical issues. During the programme, the presenter interviewed Mr Bell, a political cartoonist for The Guardian, concerning speculation on social media that he had been fired from the publication after drawing a cartoon that depicted the Home Secretary, Ms Priti Patel, as a bull. During the interview, the following exchange took place between the presenter and Mr Bell: Issue 425 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 26 April 2021 1 Presenter: “You’ve been sacked from The Guardian, that’s what the big reports have been! 40 years at The Guardian, and now you’re sacked! Fortunately, that’s not true. -

House of Lords Library: Gillray Collection

Library: Special Collections House of Lords Library: Gillray Collection The House of Lords Library Gillray collection was acquired in 1899 as a bequest from Sir William Augustus Fraser (1826–1898). The collection consists of eleven folio volumes, retaining Fraser’s fine bindings: half red morocco with elaborate gold tooling on the spines. Ownership bookplates on the verso of the front boards show Fraser’s coat of arms and some of the prints bear his “cinquefoil in sunburst” collector’s mark. The volumes are made up of leaves of blue paper, on to which the prints are pasted. Perhaps surprisingly, given the age of the paper and adhesive, there is no evident damage to the prints. Due to the prints being stored within volumes, light damage has been minimised and the colour is still very vibrant. The collection includes a few caricatures by other artists (such as Thomas Rowlandson) but the majority are by Gillray. It is possible that the prints by other artists were mistakenly attributed to Gillray by Fraser. Where Fraser lacked a particular print he pasted a marker at the relevant chronological point in the volume, noting the work he still sought. These markers have been retained in the collection and are listed in the Catalogue. The collection includes some early states of prints, such as Britania in French Stays and a few prints that are not held in the British Museum’s extensive collection. For example, Grattan Addresses the Mob is listed in Dorothy George’s Catalogue as part of the House of Lords Library’s collection only.1 Volume I includes a mezzotint portrait of the author by Charles Turner, and two manuscript letters written by Gillray; one undated and addressed to the artist Benjamin West; the other dated 1797 and addressed to the publisher John Wright. -

Trump, Biden Fight It out to The

P2JW308000-6-A00100-17FFFF5178F ****** TUESDAY,NOVEMBER 3, 2020 ~VOL. CCLXXVI NO.106 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 DJIA 26925.05 À 423.45 1.6% NASDAQ 10957.61 À 0.4% STOXX 600 347.86 À 1.6% 10-YR. TREAS. À 3/32 , yield 0.848% OIL $36.81 À $1.02 GOLD $1,890.40 À $13.00 EURO $1.1641 YEN 104.75 What’s AP News PEREZ/ MICHAEL P; Business&Finance /A /PTR arket turbulence has DUNLAP Mdisrupted adriveby nonbank mortgagefirms to SHANE P; raise capital through public /A listings, with two major lend- ersrecently delaying IPOs. A1 HARNIK TwitterCEO Dorsey’s job appearssafeafter aboard ANDREW committeerecommended P; /A that the current management AR structureremain in place. B1 PUSK J. Chinese regulators met GENE with Jack Ma and topAnt : Group executives,days before LEFT the company’sstock is set P to begin trading publicly. B1 TO OM Walmart has ended its FR effort to use roving robots WISE in store aisles to keep OCK track of its inventory. B1 CL In Pennsylvania on Monday, President Trump spoke at a rally at the Wilkes-Barre/Scranton airport; Joe Biden attended a rally in Monaca; Vice President Factories across the Mike Pence, along with his wife, Karen, and daughter Charlotte were in Latrobe; and vice-presidential candidate Sen. Kamala Harris was in Pittston. globe bounced back strongly in October, as manufactur- ers hired more people and ramped up production. A2 Trump,Biden FightItOut to theEnd U.S. stocks rose, with the Dow, S&P 500 and against abackdrop of concerns states were steeling themselves Trump spent the closing days of astate,Ohio,that shifteddeci- Nasdaq gaining 1.6%, 1.2% Election officials steel over the vote-counting process foradrawn-out vote-counting the campaign questioning ex- sively behind Mr.Trump and and 0.4%, respectively. -

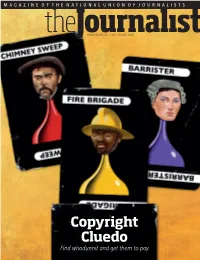

Copyright Cluedo Find Whodunnit and Get Them to Pay Contents

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | JULY-AUGUST 2018 Copyright Cluedo Find whodunnit and get them to pay Contents Main feature 12 Close in and win The quest for copyright justice News opyright has been under sustained 03 STV cuts jobs and closes channel attack in the digital age, whether it is through flagrant breaches by people Pledge for no compulsory redundancies hoping they can use photos and 04 Call for more disabled people on TV content without paying or genuine NUJ backs campaign at TUC conference Cignorance by some who believe that if something is downloadable then it’s free. Photographers 05 Legal action to demand Leveson Two and the NUJ spend a lot of time and energy chasing copyright. Victims get court go-ahead This edition’s cover feature by Mick Sinclair looks at a range of 07 Al Jazeera staff win big pay rise practical, good-spirited ways of making sure you’re paid what Deal reached after Acas talks you’re owed. It can take a bit of detective work. Data in all its forms is another big theme of this edition. “Whether it’s working within the confines of the new general Features data protection regulations or finding the best way to 10 Business as usual? communicate securely with sources, data is an increasingly What new data rules mean for the media important part of our work. Ruth Addicott looks at the implications of the new data laws for journalists and Simon 13 Safe & secure Creasey considers the best forms of keeping communication How to communicate confidentially with sources private.