Fluid Equations, Magnetohydrodynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Chapter 3 Dynamics of the Electromagnetic Fields

Chapter 3 Dynamics of the Electromagnetic Fields 3.1 Maxwell Displacement Current In the early 1860s (during the American civil war!) electricity including induction was well established experimentally. A big row was going on about theory. The warring camps were divided into the • Action-at-a-distance advocates and the • Field-theory advocates. James Clerk Maxwell was firmly in the field-theory camp. He invented mechanical analogies for the behavior of the fields locally in space and how the electric and magnetic influences were carried through space by invisible circulating cogs. Being a consumate mathematician he also formulated differential equations to describe the fields. In modern notation, they would (in 1860) have read: ρ �.E = Coulomb’s Law �0 ∂B � ∧ E = − Faraday’s Law (3.1) ∂t �.B = 0 � ∧ B = µ0j Ampere’s Law. (Quasi-static) Maxwell’s stroke of genius was to realize that this set of equations is inconsistent with charge conservation. In particular it is the quasi-static form of Ampere’s law that has a problem. Taking its divergence µ0�.j = �. (� ∧ B) = 0 (3.2) (because divergence of a curl is zero). This is fine for a static situation, but can’t work for a time-varying one. Conservation of charge in time-dependent case is ∂ρ �.j = − not zero. (3.3) ∂t 55 The problem can be fixed by adding an extra term to Ampere’s law because � � ∂ρ ∂ ∂E �.j + = �.j + �0�.E = �. j + �0 (3.4) ∂t ∂t ∂t Therefore Ampere’s law is consistent with charge conservation only if it is really to be written with the quantity (j + �0∂E/∂t) replacing j. -

Non-Local Momentum Transport Parameterizations

Non-local Momentum Transport Parameterizations Joe Tribbia NCAR.ESSL.CGD.AMP Outline • Historical view: gravity wave drag (GWD) and convective momentum transport (CMT) • GWD development -semi-linear theory -impact • CMT development -theory -impact Both parameterizations of recent vintage compared to radiation or PBL GWD CMT • 1960’s discussion by Philips, • 1972 cumulus vorticity Blumen and Bretherton damping ‘observed’ Holton • 1970’s quantification Lilly • 1976 Schneider and and momentum budget by Lindzen -Cumulus Friction Swinbank • 1980’s NASA GLAS model- • 1980’s incorporation into Helfand NWP and climate models- • 1990’s pressure term- Miller and Palmer and Gregory McFarlane Atmospheric Gravity Waves Simple gravity wave model Topographic Gravity Waves and Drag • Flow over topography generates gravity (i.e. buoyancy) waves • <u’w’> is positive in example • Power spectrum of Earth’s topography α k-2 so there is a lot of subgrid orography • Subgrid orography generating unresolved gravity waves can transport momentum vertically • Let’s parameterize this mechanism! Begin with linear wave theory Simplest model for gravity waves: with Assume w’ α ei(kx+mz-σt) gives the dispersion relation or Linear theory (cont.) Sinusoidal topography ; set σ=0. Gives linear lower BC Small scale waves k>N/U0 decay Larger scale waves k<N/U0 propagate Semi-linear Parameterization Propagating solution with upward group velocity In the hydrostatic limit The surface drag can be related to the momentum transport δh=isentropic Momentum transport invariant by displacement Eliassen-Palm. Deposited when η=U linear theory is invalid (CL, breaking) z φ=phase Gravity Wave Drag Parameterization Convective or shear instabilty begins to dissipate wave- momentum flux no longer constant Waves propagate vertically, amplitude grows as r-1/2 (energy force cons.). -

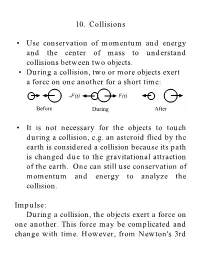

10. Collisions • Use Conservation of Momentum and Energy and The

10. Collisions • Use conservation of momentum and energy and the center of mass to understand collisions between two objects. • During a collision, two or more objects exert a force on one another for a short time: -F(t) F(t) Before During After • It is not necessary for the objects to touch during a collision, e.g. an asteroid flied by the earth is considered a collision because its path is changed due to the gravitational attraction of the earth. One can still use conservation of momentum and energy to analyze the collision. Impulse: During a collision, the objects exert a force on one another. This force may be complicated and change with time. However, from Newton's 3rd Law, the two objects must exert an equal and opposite force on one another. F(t) t ti tf Dt From Newton'sr 2nd Law: dp r = F (t) dt r r dp = F (t)dt r r r r tf p f - pi = Dp = ò F (t)dt ti The change in the momentum is defined as the impulse of the collision. • Impulse is a vector quantity. Impulse-Linear Momentum Theorem: In a collision, the impulse on an object is equal to the change in momentum: r r J = Dp Conservation of Linear Momentum: In a system of two or more particles that are colliding, the forces that these objects exert on one another are internal forces. These internal forces cannot change the momentum of the system. Only an external force can change the momentum. The linear momentum of a closed isolated system is conserved during a collision of objects within the system. -

Lecture 7: Moments of the Boltzmann Equation

!"#$%&'()%"*#%*+,-./-*+01.2(.*3+456789* !"#$%&"'()'*+,"-$.'+/'0+1$2,3--4513.+6'78%39+-' Dr. Peter T. Gallagher Astrophysics Research Group Trinity College Dublin :2;$-$(01*%<*=,-./-*=0;"%/;"-* !"#$%#&!'()*%()#& +,)-"(./#012"(& 4,$50,671*)& 9*"5:%#))& 3*1*)& 87)21*)& ;<7#1*)& 3*%()5$&*=&9*"5:%#))& ;<7#1*)& +,)-"(&>7,?& 37"1/"(&& 3@4& >7,?$& >%/;"#.*%<*?%,#@/-""AB,-.%C*DE'-)%"* o Under certain assumptions not necessary to obtain actual distribution function if only interested in the macroscopic values. o Instead of solving Boltzmann or Vlasov equation for distribution function and integrating, can take integrals over collisional Boltzmann-Vlasov equation and solve for the quantities of interest. "f q "f & "f ) +v #$f + [E +(v % B)]# = ( + "t m "v ' "t *coll (7.1) o Called “taking the moments of the Boltzmann-Vlasov equation” . ! o Resulting equations known as the macroscopic transport equations, and form the foundation of plasma fluid theory. o Results in derivation of the equations of magnetohydrodynamics (MHD). F;$%#0A%$&;$*>%/;"#G*H%")"'2#1*DE'-)%"* o Lowest order moment obtained by integrating Eqn. 7.1: "f q "f ' "f * # dv + # v $%fdv + # [E +(v & B)]$ dv = # ) , dv "t m "v ( "t +coll The first term gives "f " "n o # dv = # fdv = (7.2) "t "t "t ! o Since v and r are independent, v is not effected by gradient operator: ! $ v " #fdv = # " $ vfdv o From before, the first order moment of distribution function is ! 1 u = " vf (r,v,t)dv n therefore, $ v " #fdv = # "(nu) (7.3) ! ! F;$%#0A%$&;$*>%/;"#G*H%")"'2#1*DE'-)%"* o For the third term, consider E and B separately. E term vanishes as #f # $ E " dv = $ "( fE)dv = $ fE "dS = 0 (7.4a) #v #v using Gauss’ Divergence Theorem in velocity space. -

Fluids – Lecture 7 Notes 1

Fluids – Lecture 7 Notes 1. Momentum Flow 2. Momentum Conservation Reading: Anderson 2.5 Momentum Flow Before we can apply the principle of momentum conservation to a fixed permeable control volume, we must first examine the effect of flow through its surface. When material flows through the surface, it carries not only mass, but momentum as well. The momentum flow can be described as −→ −→ momentum flow = (mass flow) × (momentum /mass) where the mass flow was defined earlier, and the momentum/mass is simply the velocity vector V~ . Therefore −→ momentum flow =m ˙ V~ = ρ V~ ·nˆ A V~ = ρVnA V~ where Vn = V~ ·nˆ as before. Note that while mass flow is a scalar, the momentum flow is a vector, and points in the same direction as V~ . The momentum flux vector is defined simply as the momentum flow per area. −→ momentum flux = ρVn V~ V n^ . mV . A m ρ Momentum Conservation Newton’s second law states that during a short time interval dt, the impulse of a force F~ applied to some affected mass, will produce a momentum change dP~a in that affected mass. When applied to a fixed control volume, this principle becomes F dP~ a = F~ (1) dt V . dP~ ˙ ˙ P(t) P + P~ − P~ = F~ (2) . out dt out in Pin 1 In the second equation (2), P~ is defined as the instantaneous momentum inside the control volume. P~ (t) ≡ ρ V~ dV ZZZ ˙ The P~ out is added because mass leaving the control volume carries away momentum provided ˙ by F~ , which P~ alone doesn’t account for. -

The Vlasov-Poisson System and the Boltzmann Equation

DISCRETE AND CONTINUOUS Website: http://AIMsciences.org DYNAMICAL SYSTEMS Volume 8, Number 2, April 2002 pp. 361–380 AN INTRODUCTION TO KINETIC EQUATIONS: THE VLASOV-POISSON SYSTEM AND THE BOLTZMANN EQUATION JEAN DOLBEAULT Abstract. The purpose of kinetic equations is the description of dilute par- ticle gases at an intermediate scale between the microscopic scale and the hydrodynamical scale. By dilute gases, one has to understand a system with a large number of particles, for which a description of the position and of the velocity of each particle is irrelevant, but for which the decription cannot be reduced to the computation of an average velocity at any time t ∈ R and any d position x ∈ R : one wants to take into account more than one possible veloc- ity at each point, and the description has therefore to be done at the level of the phase space – at a statistical level – by a distribution function f(t, x, v) This course is intended to make an introductory review of the literature on kinetic equations. Only the most important ideas of the proofs will be given. The two main examples we shall use are the Vlasov-Poisson system and the Boltzmann equation in the whole space. 1. Introduction. 1.1. The distribution function. The main object of kinetic theory is the distri- bution function f(t, x, v) which is a nonnegative function depending on the time: t ∈ R, the position: x ∈ Rd, the velocity: v ∈ Rd or the impulsion ξ). A basic 1 d d requirement is that f(t, ., .) belongs to Lloc (R × R ) and from a physical point of view f(t, x, v) dxdv represents “the probability of finding particles in an element of volume dxdv, at time t, at the point (x, v) in the (one-particle) phase space”. -

Plasma Physics I APPH E6101x Columbia University Fall, 2016

Lecture 1: Plasma Physics I APPH E6101x Columbia University Fall, 2016 1 Syllabus and Class Website http://sites.apam.columbia.edu/courses/apph6101x/ 2 Textbook “Plasma Physics offers a broad and modern introduction to the many aspects of plasma science … . A curious student or interested researcher could track down laboratory notes, older monographs, and obscure papers … . with an extensive list of more than 300 references and, in particular, its excellent overview of the various techniques to generate plasma in a laboratory, Plasma Physics is an excellent entree for students into this rapidly growing field. It’s also a useful reference for professional low-temperature plasma researchers.” (Michael Brown, Physics Today, June, 2011) 3 Grading • Weekly homework • Two in-class quizzes (25%) • Final exam (50%) 4 https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sdo/overview/ Launched 11 Feb 2010 5 http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sdo/news/sdo-year2.html#.VerqQLRgyxI 6 http://www.ccfe.ac.uk/MAST.aspx http://www.ccfe.ac.uk/mast_upgrade_project.aspx 7 https://youtu.be/svrMsZQuZrs 8 9 10 ITER: The International Burning Plasma Experiment Important fusion science experiment, but without low-activation fusion materials, tritium breeding, … ~ 500 MW 10 minute pulses 23,000 tonne 51 GJ >30B $US (?) DIII-D ⇒ ITER ÷ 3.7 (50 times smaller volume) (400 times smaller energy) 11 Prof. Robert Gross Columbia University Fusion Energy (1984) “Fusion has proved to be a very difficult challenge. The early question was—Can fusion be done, and, if so how? … Now, the challenge lies in whether fusion can be done in a reliable, an economical, and socially acceptable way…” 12 http://lasco-www.nrl.navy.mil 13 14 Plasmasphere (Image EUV) 15 https://youtu.be/TaPgSWdcYtY 16 17 LETTER doi:10.1038/nature14476 Small particles dominate Saturn’s Phoebe ring to surprisingly large distances Douglas P. -

Plasma Physics and Advanced Fluid Dynamics Jean-Marcel Rax (Univ. Paris-Saclay, Ecole Polytechnique), Christophe Gissinger (LPEN

Plasma Physics and advanced fluid dynamics Jean-Marcel Rax (Univ. Paris-Saclay, Ecole Polytechnique), Christophe Gissinger (LPENS)) I- Plasma Physics : principles, structures and dynamics, waves and instabilities Besides ordinary temperature usual (i) solid state, (ii) liquid state and (iii) gaseous state, at very low and very high temperatures new exotic states appear : (iv) quantum fluids and (v) ionized gases. These states display a variety of specific and new physical phenomena : (i) at low temperature quantum coherence, correlation and indiscernibility lead to superfluidity, su- perconductivity and Bose-Einstein condensation ; (ii) at high temperature ionization provides a significant fraction of free charges responsible for in- stabilities, nonlinear, chaotic and turbulent behaviors characteristic of the \plasma state". This set of lectures provides an introduction to the basic tools, main results and advanced methods of Plasma Physics. • Plasma Physics : History, orders of magnitudes, Bogoliubov's hi- erarchy, fluid and kinetic reductions. Electric screening : Langmuir frequency, Maxwell time, Debye length, hybrid frequencies. Magnetic screening : London and Kelvin lengths. Alfven and Bohm velocities. • Charged particles dynamics : adiabaticity and stochasticity. Alfven and Ehrenfest adiabatic invariants. Electric and magnetic drifts. Pon- deromotive force. Wave/particle interactions : Chirikov criterion and chaotic dynamics. Quasilinear kinetic equation for Landau resonance. • Structure and self-organization : Debye and Child-Langmuir sheath, Chapman-Ferraro boundary layer. Brillouin and basic MHD flow. Flux conservation : Alfven's theorem. Magnetic topology : magnetic helicity conservation. Grad-Shafranov and basic MHD equilibrium. • Waves and instabilities : Fluid and kinetic dispersions : resonance and cut-off. Landau and cyclotron absorption. Bernstein's modes. Fluid instabilities : drift, interchange and kink. Alfvenic and geometric coupling. -

This Chapter Deals with Conservation of Energy, Momentum and Angular Momentum in Electromagnetic Systems

This chapter deals with conservation of energy, momentum and angular momentum in electromagnetic systems. The basic idea is to use Maxwell’s Eqn. to write the charge and currents entirely in terms of the E and B-fields. For example, the current density can be written in terms of the curl of B and the Maxwell Displacement current or the rate of change of the E-field. We could then write the power density which is E dot J entirely in terms of fields and their time derivatives. We begin with a discussion of Poynting’s Theorem which describes the flow of power out of an electromagnetic system using this approach. We turn next to a discussion of the Maxwell stress tensor which is an elegant way of computing electromagnetic forces. For example, we write the charge density which is part of the electrostatic force density (rho times E) in terms of the divergence of the E-field. The magnetic forces involve current densities which can be written as the fields as just described to complete the electromagnetic force description. Since the force is the rate of change of momentum, the Maxwell stress tensor naturally leads to a discussion of electromagnetic momentum density which is similar in spirit to our previous discussion of electromagnetic energy density. In particular, we find that electromagnetic fields contain an angular momentum which accounts for the angular momentum achieved by charge distributions due to the EMF from collapsing magnetic fields according to Faraday’s law. This clears up a mystery from Physics 435. We will frequently re-visit this chapter since it develops many of our crucial tools we need in electrodynamics. -

Leonhard Euler: His Life, the Man, and His Works∗

SIAM REVIEW c 2008 Walter Gautschi Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 3–33 Leonhard Euler: His Life, the Man, and His Works∗ Walter Gautschi† Abstract. On the occasion of the 300th anniversary (on April 15, 2007) of Euler’s birth, an attempt is made to bring Euler’s genius to the attention of a broad segment of the educated public. The three stations of his life—Basel, St. Petersburg, andBerlin—are sketchedandthe principal works identified in more or less chronological order. To convey a flavor of his work andits impact on modernscience, a few of Euler’s memorable contributions are selected anddiscussedinmore detail. Remarks on Euler’s personality, intellect, andcraftsmanship roundout the presentation. Key words. LeonhardEuler, sketch of Euler’s life, works, andpersonality AMS subject classification. 01A50 DOI. 10.1137/070702710 Seh ich die Werke der Meister an, So sehe ich, was sie getan; Betracht ich meine Siebensachen, Seh ich, was ich h¨att sollen machen. –Goethe, Weimar 1814/1815 1. Introduction. It is a virtually impossible task to do justice, in a short span of time and space, to the great genius of Leonhard Euler. All we can do, in this lecture, is to bring across some glimpses of Euler’s incredibly voluminous and diverse work, which today fills 74 massive volumes of the Opera omnia (with two more to come). Nine additional volumes of correspondence are planned and have already appeared in part, and about seven volumes of notebooks and diaries still await editing! We begin in section 2 with a brief outline of Euler’s life, going through the three stations of his life: Basel, St. -

Plasma Descriptions I: Kinetic, Two-Fluid 1

CHAPTER 5. PLASMA DESCRIPTIONS I: KINETIC, TWO-FLUID 1 Chapter 5 Plasma Descriptions I: Kinetic, Two-Fluid Descriptions of plasmas are obtained from extensions of the kinetic theory of gases and the hydrodynamics of neutral uids (see Sections A.4 and A.6). They are much more complex than descriptions of charge-neutral uids because of the complicating eects of electric and magnetic elds on the motion of charged particles in the plasma, and because the electric and magnetic elds in the plasma must be calculated self-consistently with the plasma responses to them. Additionally, magnetized plasmas respond very anisotropically to perturbations — because charged particles in them ow almost freely along magnetic eld lines, gyrate about the magnetic eld, and drift slowly perpendicular to the magnetic eld. The electric and magnetic elds in a plasma are governed by the Maxwell equations (see Section A.2). Most calculations in plasma physics assume that the constituent charged particles are moving in a vacuum; thus, the micro- scopic, “free space” Maxwell equations given in (??) are appropriate. For some applications the electric and magnetic susceptibilities (and hence dielectric and magnetization responses) of plasmas are derived (see for example Sections 1.3, 1.4 and 1.6); then, the macroscopic Maxwell equations are used. Plasma eects enter the Maxwell equations through the charge density and current “sources” produced by the response of a plasma to electric and magnetic elds: X X q = nsqs, J = nsqsVs, plasma charge, current densities. (5.1) s s Here, the subscript s indicates the charged particle species (s = e, i for electrons, 3 ions), ns is the density (#/m ) of species s, qs the charge (Coulombs) on the species s particles, and Vs the species ow velocity (m/s).