Identifying British Elms Ulmus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

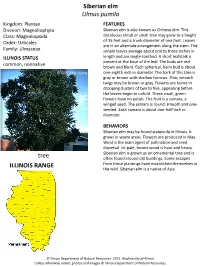

Siberian Elm Ulmus Pumila ILLINOIS RANGE Tree

Siberian elm Ulmus pumila Kingdom: Plantae FEATURES Division: Magnoliophyta Siberian elm is also known as Chinese elm. This Class: Magnoliopsida deciduous shrub or small tree may grow to a height Order: Urticales of 35 feet and a trunk diameter of one foot. Leaves are in an alternate arrangement along the stem. The Family: Ulmaceae simple leaves average about one to three inches in ILLINOIS STATUS length and are single-toothed. A short leafstalk is present at the base of the leaf. The buds are red- common, nonnative brown and blunt. Each spherical, hairy bud is about © Guy Sternberg one-eighth inch in diameter. The bark of this tree is gray or brown with shallow furrows. Thin, smooth twigs may be brown or gray. Flowers are borne in drooping clusters of two to five, appearing before the leaves begin to unfold. These small, green flowers have no petals. The fruit is a samara, a winged seed. The samara is round, smooth and one- seeded. Each samara is about one-half inch in diameter. BEHAVIORS Siberian elm may be found statewide in Illinois. It grows in waste areas. Flowers are produced in May. Wind is the main agent of pollination and seed dispersal. Its pale, brown wood is hard and heavy. Siberian elm is grown as an ornamental tree and is tree often found around old buildings. Some escapes from these plantings have established themselves in ILLINOIS RANGE the wild. Siberian elm is a native of Asia. © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

Stegophora Ulmea

EuropeanBlackwell Publishing, Ltd. and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization Organisation Européenne et Méditerranéenne pour la Protection des Plantes Data sheets on quarantine pests Fiches informatives sur les organismes de quarantaine Stegophora ulmea widespread from the Great Plains to the Atlantic Ocean. Sydow Identity (1936) reported a foliar disease of Ulmus davidiana caused by Name: Stegophora ulmea (Fries) Sydow & Sydow Stegophora aemula in China stating that the pathogen differs Synonyms: Gnomonia ulmea (Fries) Thümen, Sphaeria ulmea from ‘the closely related Gnomonia ulmea’ by the ‘mode of Fries, Dothidella ulmea (Fries) Ellis & Everhart, Lambro ulmea growth’ on elm. Since, 1999, S. ulmea has repeatedly been (Fries) E. Müller detected in consignments of bonsais from China, in UK and the Taxonomic position: Fungi: Ascomycetes: Diaporthales Netherlands, suggesting that the pathogen probably occurs in Notes on taxonomy and nomenclature: the anamorph is of China. In Europe, there is a doubtful record of ‘G. ulmicolum’ acervular type, containing both macroconidia, of ‘Gloeosporium’ on leaves and fruits of elm in Romania (Georgescu & Petrescu, type, and microconidia, of ‘Cylindrosporella’ type. Various cited by Peace (1962)), which has not been confirmed since. In anamorph names in different form-genera have been the Netherlands, S. ulmea was introduced into a glasshouse in used (‘Gloeosporium’ ulmeum ‘Gloeosporium’ ulmicolum, 2000, on ornamental bonsais, but was successfully eradicated Cylindrosporella ulmea, Asteroma ulmeum), -

Lacebark Elm Cultivars Ulmus Parvifolia

Lacebark Elm Cultivars Ulmus parvifolia P O Box 189 | Boring OR 97009 | 800-825-8202 | www.jfschmidt.com Ulmus parvifolia ‘Emer II’ PP 7552 Tall, upright and arching, this cultivar’s growth habit is unique Allee® Elm among U. parvifolia cultivars, Zone: 5 | Height: 50' | Spread: 35' being reminiscent of the grand Shape: Upright vase, arching American Elm. Its exfoliating Foliage: Medium green, glossy bark creates a mosaic of orange, Fall Color: Yellow-orange to rust red tan and gray, a beautiful sight on a mature tree. Discovered by DISEASE TOLERANCE: Dr. Michael Dirr of University of Dutch Elm Disease and phloem Georgia, Athens. necrosis Ulmus parvifolia ‘Emer I’ Bark of a mature tree is a mosaic of orange, tan, and gray patches, Athena® Classic Elm giving it as much interest in winter Zone: 5 | Height: 30' | Spread: 35' as in summer. The canopy is tightly Shape: Broadly rounded formed. Discovered by Dr. Michael Foliage: Medium green, glossy Dirr of University of Georgia, Fall Color: Yellowish Athens. DISEASE TOLERANCE: Dutch Elm Disease and phloem necrosis Ulmus parvifolia ‘UPMTF’ PP 11295 Bosque® is well shaped for plant- ing on city streets and in restricted Bosque® Elm spaces, thanks to its upright Zone: 6 | Height: 45' | Spread: 30' growth habit and narrow crown. Shape: Upright pyramidal to Fine textured and glossy, its dark broadly oval green foliage is complemented by Foliage: Dark green, glossy multi-colored exfoliating bark. Fall Color: Yellow-orange DISEASE TOLERANCE: Dutch Elm Disease and phloem necrosis Ulmus parvifolia ‘Dynasty’ A broadly rounded tree with fine textured foliage and good Dynasty Elm environ mental tolerance. -

The Elms of Co Cork- a Survey of Species, Varieties and Forms

IRISH FORESTRY The elms of Co Cork- a survey of species, varieties and forms Gordon L. Mackenthun' Abstract In a survey of the elms in County Cork, Ireland, some 50 single trees, groups of trees and populations were examined. Four main taxa were recognised, these being 'W)'ch elm, Cornish elm, Coritanian elm and Dutch elm plus a number of ambiguous hybrids. While a large overall number of elms were found, the number of mature or even ancient elms is relatively small. Still, there are sufficient numbers of elms in the county to base a future elm protection programme 011. Keywords Ulmus, 'N)'ch elm, field elm, hybrid elm, Dutch elm disease. Introduction Elm taxonomy is known to be notoriously difficult. For the British Isles there are many different concepts, varying between just two elm species and more than one hundred so-called microspecies (Richens 1983, Armstrong 1992, Armstrong and Sell 1996). The main reason for the difficulty with elm taxonomy lies in the fact that the variability within the genus is extreme. This is especially tme for the group of elms we know under the name field elm. As a result, there is no generally accepted system for classification of the elms of the world. Some British researchers claim to host up to eight elm species in their country (Melville 1975, Clapham et a1. 1987, Stace 1997). The approach taken here follows the lines being drawn by Richard H. Richens (1983) who followed a fairly simple strategy. He assumcd that there are just two species of elms prescnt in the British Isles, the native wych elm, Ulmus glabra and the introduced field ehil, U minor. -

Morphological Characteristics and Water-Use Efficiency of Siberian Elm Trees (Ulmus Pumila L.) Within Arid Regions of Northeast

Article Morphological Characteristics and Water-Use Efficiency of Siberian Elm Trees (Ulmus pumila L.) within Arid Regions of Northeast Asia Go Eun Park 1, Don Koo Lee 2,†, Ki Woo Kim 3,†, Nyam-Osor Batkhuu 4,†, Jamsran Tsogtbaatar 5,†, Jiao-Jun Zhu 6,†, Yonghuan Jin 6,†, Pil Sun Park 2,†, Jung Oh Hyun 2,† and Hyun Seok Kim 2,7,8,9,* 1 Center for Forest and Climate Change, National Institute of Forest Science, Seoul 02455, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Forest Sciences, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Korea; [email protected] (D.K.L.); [email protected] (P.S.P.); [email protected] (J.O.H.) 3 School of Ecology and Environmental System, Kyungpook National University, Sangju 37224, Korea; [email protected] 4 Department of Forestry, National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar 210646, Mongolia; [email protected] 5 Institute of Geoecology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Ulaanbaatar 211238, Mongolia; [email protected] 6 Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenyang 110016, China; [email protected] (J.-J.Z.); [email protected] (Y.J.) 7 Institute of Future Environmental and Forest Resources, Research Institute for Agriculture and Life Sciences, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Korea 8 National Center for Agro Meteorology, Seoul 08826, Korea 9 Interdisciplinary Program in Agriculture and Forest Meteorology, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-880-4752; Fax: +82-2-873-3560 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Academic Editors: Jarmo K. Holopainen and Timothy A. Martin Received: 31 August 2016; Accepted: 8 November 2016; Published: 17 November 2016 Abstract: The Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila L.) is one of the most commonly found tree species in arid areas of northeast Asia. -

Lacebark Elm Scientific Name: Ulmus Parvifolia Order

Common Name: Lacebark Elm Scientific Name: Ulmus parvifolia Order: Urticales Family: Ulmaceae Description The leaf arrangement of the lacebark elm (also known as Chinese elm) is alternate. Each leaf is oval with a serrate margin. Typical leaf coloration is leathery green, with purple, red, and yellow in the fall. The tree grows to a height of 40 to 50 feet with a spread of 35 to 50 feet. The bark is thin, thus giving rise to its common name as the lacebark elm. The tree produces a hard and dry fruit that brown and typically less than .5 inches in length. The root system contains a number of large-diameter members located close to the surface, and can grow for a long distance from the trunk. Growth Habit Lacebark elm is deciduous, but has been known to be evergreen in the southern extent of its range. The trees typically have a single trunk, although some have split trunks. They typically grow to a mature height of over 10 – 12 feet. It produces a bloom from late summer to fall which is yellow to green in color. A fruit is set in the fall. Hardiness Zone(s) The USDA hardiness zones for this plant are 5B through 10A. Culture Lacebark elm has no demanding culture for its habitat, and is considered to be quite hardy. It grows well in part shade as well as full sun, and has a high drought tolerance. For habitats near ocean, it has a moderate air-borne salt tolerance. For soils, it tolerates nearly all types, from clay, to sand, to loam. -

'Camperdownii' Samt Ulmus Minor 'Hoersholmiensis'

Efter almsjukan Förslag till ersättare för Ulmus glabra, Ulmus glabra ©Camperdownii© samt Ulmus minor ©Hoersholmiensis© Självständigt arbete vid LTJ-fakulteten, SLU Landskapsingenjörsprogrammet 2009 Marcus Persson SLU, Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet Fakulteten för landskapsplanering, trädgårds- och jordbruksvetenskap, LTJ Författare: Marcus Persson Titel: Ersättare för alm Nyckelord: Ulmus, glabra, Camperdownii, minor, Hoersholmiensis, alm, almsjuka, ersättare. Handledare: Mark Huisman Examinator: Eva-Lou Gustafsson Kurstitel: Examensarbete för Landskapsingenjörer Kurskod: EX0359 Omfattning, högskolepoäng: 15hp Nivå och fördjupning: C-nivå Utgivningsort: Alnarp Utgivningsår: 2009 Fotot på försättsbladet är en frisk Ulmus glabra vilken är i full gång att slå ut sina blad på försommaren. Trädet är planterat år 1859 utanför gamla fängelset i Visby hamn. Foto av Arne Persson. II Förord Detta examensarbete är skrivet vid Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet, SLU, fakulteten för landskapsplanering, trädgårds- och jordbruksvetenskap inom Landskapsingenjörsprogrammet. Ämnet är landskapsplanering. Jag skulle vilja tacka min handledare Mark Huisman för att ha gett sig tid och stöttat mig igenom hela arbetet. Jag skulle även vilja tacka de som har bidragit med fotografier. III Sammanfattning Jag valde att skriva om ersättare för alm då jag sett almar av olika slag dö bort och försvinna i städer, parker och andra platser med ett snabbt förlopp på grund av almsjukan. Under sommaren 2008 när jag arbetade med att inventera alm och almsjuka på Gotland väcktes frågan om vilket träd som skulle kunna ersätta almen. Sedan den aggressiva formen av almsjuka kom till Sverige under 1980 ± talet har många almar fått ge vika. Almsjukan är en vissningssjukdom vilken uppstår då en svamp täpper till trädets kärlsträngar. Detta bidrar till att trädet inte får någon tillgång till vatten och näring. -

New York Non-Native Plant Invasiveness Ranking Form

NEW YORK NON-NATIVE PLANT INVASIVENESS RANKING FORM Scientific name: Ulmus pumila L. USDA Plants Code: ULPU Common names: Siberian elm Native distribution: Asia Date assessed: October 18, 2009 Assessors: Gerry Moore Reviewers: LIISMA SRC Date Approved: Form version date: 10 July 2009 New York Invasiveness Rank: Moderate (Relative Maximum Score 50.00-69.99) Distribution and Invasiveness Rank (Obtain from PRISM invasiveness ranking form) PRISM Status of this species in each PRISM: Current Distribution Invasiveness Rank 1 Adirondack Park Invasive Program Not Assessed Not Assessed 2 Capital/Mohawk Not Assessed Not Assessed 3 Catskill Regional Invasive Species Partnership Not Assessed Not Assessed 4 Finger Lakes Not Assessed Not Assessed 5 Long Island Invasive Species Management Area Widespread Moderate 6 Lower Hudson Not Assessed Not Assessed 7 Saint Lawrence/Eastern Lake Ontario Not Assessed Not Assessed 8 Western New York Not Assessed Not Assessed Invasiveness Ranking Summary Total (Total Answered*) Total (see details under appropriate sub-section) Possible 1 Ecological impact 40 (20) 3 2 Biological characteristic and dispersal ability 25 (25) 19 3 Ecological amplitude and distribution 25 (25) 17 4 Difficulty of control 10 (10) 3 Outcome score 100 (80)b 42.00a † Relative maximum score 52.50 § New York Invasiveness Rank Moderate (Relative Maximum Score 50.00-69.99) * For questions answered “unknown” do not include point value in “Total Answered Points Possible.” If “Total Answered Points Possible” is less than 70.00 points, then the overall invasive rank should be listed as “Unknown.” †Calculated as 100(a/b) to two decimal places. §Very High >80.00; High 70.00−80.00; Moderate 50.00−69.99; Low 40.00−49.99; Insignificant <40.00 Not Assessable: not persistent in NY, or not found outside of cultivation. -

Ulmus 'Patriot'

Ulmus ‘Patriot’ The U.S. National Arboretum presents Ulmus ‘Patriot’, a hybrid elm for planting sites demanding a big, tough tree. ‘Patriot’ was bred and selected for pest and disease tolerance and a wide, vase-shaped crown. Fast-growing and highly tolerant to Dutch elm disease, it is easily established in the nursery or landscape. Select ‘Patriot’ for those park, lawn or highway sites requiring a tree of exceptional vigor. U.S. National Arboretum Plant Introduction Floral and Nursery Plants Research Unit U.S. National Arboretum, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 3501 New York Ave. NE., Washington, DC 20002 ‘Patriot’ hybrid elm Botanical name: Ulmus ‘Patriot’ (U. ‘Urban’ × U. davidiana var. japonica ‘Prospector’) (NA 60071; PI 566597) Family: Ulmaceae Hardiness: USDA Zones 4–9 Development: ‘Patriot’ resulted from a controlled pollination made in 1980 by A. M. Townsend between Ulmus 'Urban' (a complex hybrid involving U. pumila, U. ×hollandica, and U. minor) and a selection of the Asian elm U. davidiana var. japonica that was later released as ‘Prospector’. ‘Patriot’ was selected initially for its tolerance to Dutch elm disease in field inoculation studies in Delaware, Ohio, and Glenn Dale, Maryland. In further field and laboratory evaluations, ‘Patriot’ showed the highest level of elm leaf beetle tolerance of more than 600 hybrids resulting from the 1980 cross. Released 1993. Significance: ‘Patriot’ is a hybrid elm with a moderately vase-shaped crown, showing high levels of tolerance to two of the major disease and insect pests of landscape elms. It has also shown field tolerance to natural infections of elm yellows. -

Elm Bark Beetles Native and Introduced Bark Beetles of Elm

Elm Bark Beetles Native and introduced bark beetles of elm Name and Description—Native elm bark beetle—Hylurgopinus rufipes Eichhoff Smaller European elm bark beetle—Scolytus multistriatus (Marsham) Banded elm bark beetle—S. schevyrewi Semenov [Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae] Three species of bark beetles are associated with elms in the United States: (1) the native elm bark beetle (fig. 1) occurs in Canada and south through the Lake States to Alabama and Mississippi, including Kansas and Nebraska; (2) the introduced smaller European elm bark beetle (fig.2) occurs through- out the United States; and (3) the introduced banded elm bark beetle (fig. 3) is common in western states and is spreading into states east of the Missis- sippi River. Both the smaller European elm bark beetle and the banded elm bark beetle were introduced into the United States from Europe and Asia, respectively. Hylurgopinus rufipes adults are approximately 1/12-1/10 inch (2.2-2.5 mm) long; Scolytus multistriatus adults are approximately 1/13-1/8 inch (1.9-3.1 mm) long; and S. schevyrewi adults are approximately 1/8-1/6 inch (3-4 mm) long. The larvae are white, legless grubs. Hosts—Hosts for the native elm bark beetle include the various native elm Figure 1. Native elm bark beetle. Photo: J.R. species in the United States and Canada, while the introduced elm bark Baker and S.B. Bambara, North Carolina State University, Bugwood.org. beetles also infest introduced species of elms, such as English, Japanese, and Siberian elms. American elm is the primary host tree for the native elm bark beetle. -

American Elm Ulmus Americana L

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 9-1-1994 American Elm Ulmus americana L. Gene Silberhorn Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Plant Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Silberhorn, G. (1994) American Elm Ulmus americana L.. Wetland Flora Technical Reports, Wetlands Program, Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/m2-5318-he68 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wetlands Technical Report Program Wetland Flora No. 94-8 / September 1994 Gene Silberhorn American Elm Ulmus americana L. Growth Habit and Diagnostic Characteristics Habitat American elm is a large tree (up to 100 feet tall), with Once common and abundant in wooded wetlands furrowed, flaky, grayish brown bark when mature. along the Eastern Seaboard and the Midwest, Ameri- Older trees are somewhat vase-like with the branches can elm status as a important canopy component has spreading outward and upward, a feature most been greatly diminished because of the Dutch elm obvious in the winter after leaf-fall. Leaves are simple, disease, a fungus (Ophiostoma ulmii) that clogs the alternately arranged with serrated and occasionally vascular system. Ulmus americana, currently is only doubly serrated margins (toothed, interspersed with an occasional component of palustrine forested smaller teeth). Even on the same branch, leaves are wetlands in the Mid-Atlantic Region. -

Natural Hybridisation Within Elms (Ulmus L.) in Lithuania R

BALTIC FORESTRY NATURAL HYBRIDISATION WITHIN ELMS (ULMUS L.) IN LITHUANIA R. PETROKAS, V. BALIUCKAS Natural Hybridisation within Elms (Ulmus L.) in Lithuania RAIMUNDAS PETROKAS1 * AND VIRGILIJUS BALIUCKAS12 1 Institute of Forestry, Lithuanian Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry, Liepu 1, LT-53101 Girionys, Kaunas distr., Lithuania 2 Aleksandras Stulginskis University, Faculty of Forestry and Ecology, Department of Forestry, Studentu 11, LT 53361 Akademija, Kaunas distr. Lithuania *Phone: 00370 37 547289, E-mail: [email protected] Petrokas, R. and Baliuckas, V. 2012. Natural Hybridisation within Elms (Ulmus L.) in Lithuania. Baltic Forestry 18(2): 237246. Abstract Putative natural hybrids (Ulmus × hollandica) between the Smooth-leaved (Ulmus minor ssp. minor) and the Wych elm (Ulmus glabra) were observed in mixed forests along the rivers and rivulets around the central part of Lithuania. Eleven populations of elms (Ulmus L.) were studied to determine 1) the critical groups of phenotypes indicative for their taxonomic identity, 2) the variability of taxa from contact zones. Three characteristics for the trees and twenty one for their leaf, including nineteen applied by WinFOLIA 2004a programme, were used to describe each sample of the fifty eight and to ascertain the degree of affinity between samples. As a result of this approach, four taxa could be distinguished at the contact zones within elms. Three elm species and hybrids, Ulmus glabra, Ulmus minor, Ulmus laevis, and Ulmus × hollandica, were fairly satisfactorily distinguishable, but there is much overlap between the Wych elm and the Field elm in their characters that can be explained only by the equivalence of their statistically discriminant phenotypic distinctness.