Volume 63 2012 CONTENTS Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission Studies As Evangelization and Theology for World Christianity

Mission Studies as Evangelization and Teology for World Christianity Refections on Mission Studies in Britian and Ireland, 2000 - 2015 Kirsteen Kim DOI: 10.7252/Paper. 000051 About the Author Kirsteen Kim, Ph.D., is Professor of Teology and World Christianity at Leeds Trinity University. Kirsteen researches and teaches theology from the perspective of mission and world Christianity, drawing on her experience of Christianity while living and working in South Korea, India and the USA, with a special interest in theology of the Holy Spirit. She publishes widely and is the editor of Mission Studies, the journal of the International Association for Mission Studies. 72 | Mission Studies as Evangelization and Theology for World Christianity Foreword In 2000 and in 2012 I published papers for the British and Irish Association for Mission Studies (BIAMS) on mission studies in Britain and Ireland, which were published in journals of theological education.1 Tese two papers surveyed the state of mission studies and how in this region it is related to various other disciplines. Each paper suggested a next stage in the development of mission studies: the frst saw mission studies as facilitating a worldwide web of missiological discussion; the second suggested that mission studies should be appreciated as internationalizing theology more generally. Tis article reviews the developments in Britain and Ireland over the years which are detailed in these articles and bring them up to date. It further argues that, while continuing to develop as “mission studies” or “missiology”, the discipline should today claim the names “theology for world Christianity” and “studies in evangelization. -

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY SOCIETY (incorporating the Congregational Historical Society, founded in 1899, and the Presbyterian Historical Society of England founded in 1913.) . EDITOR; Dr. CLYDE BINFIELD, M.A., F.S.A. Volume 5 No.8 May 1996 CONTENTS Editorial and Notes .......................................... 438 Gordon Esslemont by Stephen Orchard, M.A., Ph.D. 439 The Origins of the Missionary Society by Stephen Orchard, M.A., Ph.D . ........................... 440 Manliness and Mission: Frank Lenwood and the London Missionary Society by Brian Stanley, M.A., Ph.D . .............................. 458 Training for Hoxton and Highbury: Walter Scott of Rothwell and his Pupils by Geoffrey F. Nuttall, F.B.A., M.A., D.D. ................... 477 Mr. Seymour and Dr. Reynolds by Edwin Welch, M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A. ....................... 483 The Presbyterians in Liverpool. Part 3: A Survey 1900-1918 by Alberta Jean Doodson, M.A., Ph.D . ....................... 489 Review Article: Only Connect by Stephen Orchard, M.A., Ph.D. 495 Review Article: Mission and Ecclesiology? Some Gales of Change by Brian Stanley, M.A., Ph.D . .............................. 499 Short Reviews by Daniel Jenkins and David M. Thompson 503 Some Contemporaries by Alan P.F. Sell, M.A., B.D., Ph.D . ......................... 505 437 438 EDITORIAL There is a story that when Mrs. Walter Peppercorn gave birth to her eldest child her brother expressed the hope that the little peppercorn would never get into a piclde. This so infuriated Mr. Peppercorn that he changed their name to Lenwood: or so his wife's family liked to believe. They were prosperous Sheffielders whom he greatly surprised by leaving a considerable fortune; he had proved to be their equal in business. -

The National Library of Australia Magazine

THE NATIONAL LIBRARY DECEMBEROF AUSTRALIA 2014 MAGAZINE KEEPSAKES PETROV POEMS GOULD’S LOST ANIMALS WILD MAN OF BOTANY BAY DEMISE OF THE EMDEN AND MUCH MORE … keepsakes australians and the great war 26 November 2014–19 July 2015 National Library of Australia Free Exhibition Gallery Open Daily 9 am–5 pm nla.gov.au #NLAkeepsakes James C. Cruden, Wedding portrait of Kate McLeod and George Searle of Coogee, Sydney, 1915, nla.pic-vn6540284 VOLUME 6 NUMBER 4 DECEMBER 2014 TheNationalLibraryofAustraliamagazine The aim of the quarterly The National Library of Australia Magazine is to inform the Australian community about the National Library of Australia’s collections and services, and its role as the information resource for the nation. Copies are distributed through the Australian library network to state, public and community libraries and most libraries within tertiary-education institutions. Copies are also made available to the Library’s international associates, and state and federal government departments and parliamentarians. Additional CONTENTS copies of the magazine may be obtained by libraries, public institutions and educational authorities. Individuals may receive copies by mail by becoming a member of the Friends of the National Library of Australia. National Library of Australia Parkes Place Keepsakes: Australians Canberra ACT 2600 02 6262 1111 and the Great War nla.gov.au Guy Hansen introduces some of the mementos NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA COUNCIL of war—personal, political and poignant—featured Chair: Mr Ryan Stokes Deputy -

FULL ISSUE (48 Pp., 2.1 MB PDF)

e Vol. 23, No.4 te atlona October 1999 etme Mission Agencies in Century 1\venty-One: How Different Will They Be? ed Ward once stated in these pages that "it will take Donald McGavran in the church growth stream of mission T brave and visionary change" for modern Christian mis theory and practice, we learn that in more recent years Wagner sions to survive (January 1982). He targeted issues such as has twice moved to quite different ministry emphases. overreliance on institutions, which too often are embarrassingly Together, all these essays illustrate how the global environ dependent on outside money, require expatriate leadership, ment changes over time, requiring substantial change in the create dependence, and overturn indigenous folkways and val forms and structure of Christian witness. Sooner or later we are ues. And he noted the refusal of many missionaries to see and brought to one of Ward's basic conclusions: As the generations acknowledge their political meaning in a world that is national pass, "new models of 'missionary' are demanded." istic, defensive, and religiously polarized, a world "where every human act has a political meaning." He charged that Western missions evidenced "inadequate willingness or capacity to ad just to the conditions requisite for ... survival." On Page Now, nearly twenty years later, Ward once again identifies 146 Repositioning Mission Agencies for the key issues, such as those just mentioned, in the theme article of Twenty-first Century this issue: "Repositioning Mission Agencies for the Twenty-first Ted Ward Century." Problems identifiable two decades ago are still with Case Studies: us, and Ward calls for rigorous evaluation and repositioning by 153 Positioning LAM for the Twenty-first Century mission executives and their boards. -

TRANSFORMING CITIES: Contested Governance and New Spatial Divisions

TRANSFORMING CITIES Transforming Cities examines the profound changes that have characterised cities of the advanced capitalist societies in the final decades of the twentieth century. It analyses ways in which relationships of contest, conflict and co-operation are realised in and through the social and spatial forms of contemporary urban life. In particular, this book focuses on the impact of economic restructuring and changing forms of urban governance on patterns of urban deprivation and social exclusion. It contends that these processes are creating new patterns of social division and new forms of regulation and control. Contributors analyse innovative strategies of urban regeneration, the shift from Fordist to post-Fordist cities, new patterns of possession and disposses sion in urban spaces, the production of cultural representations and city images, the evolution of novel forms of political power, emerging patterns of policing and surveillance, the development of partnerships between public and private agencies, the mobilisation of resistance by urban residents and implications for the empowerment of communities and individuals. Nick Jewson is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Sociology at the University of Leicester and Susanne MacGregor is Head of the School of Sociology and Social Policy at Middlesex University. TRANSFORMING CITIES contested governance and new spatial divisions Edited by NICK JEWSON and SUSANNE MACGREGOR !l Routledge ~ ~ Taylor & Francis Group LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 1997 by Routledge Published 2017 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © 1997 British Sociological Association Typeset in Baskerville by Solidus (Bristol) Limited The Open Access version of this book, available at www.tandfebooks.com, has been made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 license. -

BULLETIN Ufihe Associatfon Of131itlsh 7Htolojfcal and 'Ph Ilosophzcflll,) Jjbranes "

ISSN 0305-781X BULLETIN ufihe Associatfon of131itlsh 7htolOJfcal and 'Ph ilosophzcflll,) Jjbranes " ./ Volume 5, Number 3 November 1998 BULLETIN 1998 TIle Bulletin is published by the Association of British Theological and Philosophical Libraries as a forum for professional exchange and development in the fields of theological and philosophical librarianship. ABTAPL was founded in 1956 to bring together librarians working with or interested in theological and philosophical literature in Great Britain. The Bulletin is published three times a year (March, June and November) and now _has a circulation of approxinlately 300 copies, with about one third of that number going to libraries in Europe, North America, Japan and the Commonwealth. Subscriptions: Libraries and personal members £15.00IUS$25.00 per arulUm Retired personal members £6.00 (not posted to library addresses) Payments to the Honorary Treasurer (address below) Back Numbers: £2.00IUS$4 each (November 1989 special issue: £3.00IUS$5.50). A microfilm is available ofthe issues from 1956 to 1987. Please contact the Honorary Editor Indexes: 1974-1981 £IIUS$2; 1981-1996 £6IUS$11 Please contact the Honorary Editor Articles & Reviews: The Honorary Editor welcomes articles or reviews for consideration. Suggestions or eomments may also be sent to the address below. Advertising: Enquiries about advertising options and rates should be addressed to the Honorary Secretary (address below) COMMITTEE 1998 Chainnan Mrs Judith Powles, Librarian, Spurgeon's College, 189 South Norwood Hill, London SE25 6DJ Hon.Secretary Mr Andrew Lacey, Trinity Hall, Trinity Lane, Cambridge CB2 1TJ Hon. Treasurer: Mr Colin Rowe, Partnership House Mission Studies Library, 157 Waterloo Rd, London SEl 8XA Hon. -

PASA Journals Index 2017 07 Brian.Xlsx

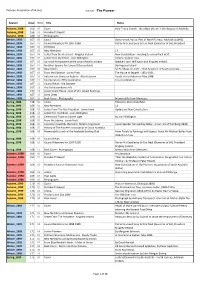

Pioneers Association of SA (Inc) Journal - "The Pioneer" Season Issue Item Title Notes Autumn_1998 166 00 Cover Holy Trinity Church - the oldest church in the diocese of Adelaide. Autumn_1998 166 01 President's Report Autumn_1998 166 02 Photographs Winter_1998 167 00 Cover Government House, Part of North Terrace, Adelaide (c1845). Winter_1998 167 01 Council Members for 1997-1998 Patron His Excellency Sir Eric Neal (Governor of SA), President Winter_1998 167 02 Portfolios Winter_1998 167 03 New Members 17 Winter_1998 167 04 Letter from the President - Kingsley Ireland New Constitution - meeting to review final draft. Winter_1998 167 05 Letter from the Editor - Joan Willington Communication lines. Winter_1998 167 06 Convivial Atmosphere at the Union Hotel Luncheon Speakers Joan Willington and Kingsley Ireland. Winter_1998 167 07 No Silver Spoons for Cavenett Descendants By Kingsley Ireland. Winter_1998 167 08 New Patron Sir Eric Neal, AC, CVO - 32nd Governor of South Australia. Winter_1998 167 09 From the Librarian - Lorna Pratt The House of Seppelt - 1851-1951. Winter_1998 167 10 Autumn sun shines on Auburn - Alan Paterson Coach trip to Auburn in May 1998. Winter_1998 167 11 Incorporation of The Association For consideration. Winter_1998 167 12 Council News - Dia Dowsett Winter_1998 167 13 The Correspondence File Winter_1998 167 14 Government House - One of SA's Oldest Buildings Winter_1998 167 15 Diary Dates Winter_1998 167 16 Back Cover - Photographs Memorabilia from Members. Spring_1998 168 00 Cover Edward Gibbon Wakefield. Spring_1998 168 01 New Members 14 Spring_1998 168 02 Letter From The Vice President - Jamie Irwin Update on New Constitution. Spring_1998 168 03 Letter fron the Editor - Joan Willington Spring_1998 168 04 Ceremonial Toast to Colonel Light By Joan Willington. -

Victoria Day Council Speech

Foreword – including the period from 1835 to Separation from NSW July 1, 1851 Gary Morgan - La Trobe Lecture, presented July 5, 2008 (Prepared over the period late July 2008 to Dec 23, 2008 and then May 2009) Since presenting my Victoria Day Council 2008 La Trobe Lecture in Queen’s Hall, Parliament House of Victoria, many people have sent me corrections, suggestions and additions; in particular Stewart McArthur, Barry Jones, and Ian Morrison. In addition Pauline Underwood and I have sourced numerous additional books, papers and other documents. They are listed as Governor Charles La Trobe. c 1851 further references at the end of this (The Roy Morgan Research Centre Pty Ltd Collection) Foreword. I expect those who study my La Trobe Lecture to advise me of which aspects they disagree with and how they could better explain the points I have covered. I do not claim to be an expert in Victorian history, or English history or any history. However, my main conclusion is Victoria and Australia ‘came of age’ during the gold miners’ ‘diggers’ confrontation with the new Victorian Government and Governor Charles La Trobe and then Governor Sir Charles Hotham. The dispute began in earnest in mid-1853 with the formation of the ‘Anti-Gold Licence Association’ established by G. E. Thomson, Dr Jones and ‘Captain’ Edward Brown – the precursor to the Eureka Stockade, December 3, 1854. The Eureka trials ‘bonded’ Victorians with a common cause and opened the way for a vibrant Victorian Colony. My LaTrobe Lecture focused on three areas: ‘Women, the Media and People from Other Countries who have helped make Melbourne and Victoria from 1851 to Today’. -

Place Name SUMMARY (PNS) 4.04.01/01 NGALTINGGA

The Southern Kaurna Place Names Project The author gratefully acknowledges the Yitpi Foundation for the grant which funded the writing of this essay. This and other essays may be downloaded free of charge from https://www.adelaide.edu.au/kwp/placenames/research-publ/ Place Name SUMMARY (PNS) 4.04.01/01 NGALTINGGA (last edited: 7.11.2017) See also PNS 4.04.01/06 Kauwi Ngaltingga anD PNS 4.04.01/03 Wakondilla NOTE AND DISCLAIMER: This essay has not been peer-reviewed or culturally endorsed in detail. The spellings and interpretations contained in it (linguistic, historical and geographical) are my own, and do not necessarily represent the views of KWP/KWK or its members or any other group. I have studied history at tertiary level. Though not a linguist, for 30 years I have learned much about the Kaurna, Ramindjeri-Ngarrindjeri and Narungga languages while working with KWP, Rob Amery, and other local culture- reclamation groups; and from primary documents I have learned much about the Aboriginal history of the Adelaide-Fleurieu region. My explorations of 'language on the land' through the Southern Kaurna Place Names Project are part of an ongoing effort to correct the record about Aboriginal place-names in this region (which has abounded in confusions and errors), and to add reliable new material into the public domain. I hope upcoming generations will continue this work and improve it. My interpretations should be amplified, re- considered and if necessary modified by KWP or other linguists, and by others engaged in cultural mapping: Aboriginal people, archaeologists, geographers, ecologists and historians. -

The Difference Donor Newsletter Spring 2010 Issue 6 Donors Make Music a Reality

How your gifts have helped... The Difference Donor Newsletter Spring 2010 Issue 6 Donors make music a reality Lead donors to the project include: o Sir Dominic Cadbury – Chancellor o Professor David Eastwood – Vice-Chancellor o Philip Eden (BA Geography, 1972) o Dr Doug Ellis (DUniv, 2008) o Simon Freakley (BCom Industrial Economics and Business Studies, 1983) o Sir David Garrard o John (BSocSc Economics, 1980) and Moyra Horseman o Phyllida Lloyd (BA English and Drama, 1979; DUniv, 2009) Lead foundation donors: o The Allan and Nesta Ferguson Instrumental role: (l-r) Major donors to the project Sir Dominic Cadbury with Liz and Terry Bramall Charitable Trust o The Charles Henry Foyle Trust Music will fill the gap in the red-brick heart of the University o The Edward Cadbury Charitable Trust campus thanks to the extraordinary generosity of donors. o The Garfield Weston Foundation o The Liz and Terry (BSc Civil Engineering, The new music building to complete the Aston showpiece facilities for the Department of 1964) Bramall Charitable Trust Webb semi-circle has received £5 million in Music. It is a wonderful opportunity for our o The Wolfson Foundation gifts and pledges and it is hoped, with further trust, which has young people, music and funding, a custom-built organ will be included education at the heart of its work.’ as an integral part of the project. The Aston Webb building was originally built Thank you for all your support! A transformational donation from the Liz and in 1909, but plans for a final dome were never Terry Bramall Charitable Trust plus extremely realised due to a shortage of funding. -

RACE RELATIONS RESEARCH in the 1990S Mapping out An

RACE RELATIONS RESEARCH IN THE 1990s Mapping out an Agenda by John Wrench and Evelyn Reid Occasional Paper in Ethnic Relations No.5 Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations February 1990 University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7AL John Wrench is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, University of Warwick. From 1976 to 1983 he was a lecturer at Aston University, first in the Sociology Group and then in the Management Centre. He has researched and published in the areas of industrial health and safety, ethnic minorities and the labour market, trade unions, and equal opportunities and the Careers Service. Evelyn Reid has worked as a lecturer for Wolverhampton Polytechnic, the University of London and the Open University. She is particularly interested in media and race and has researched and published on the subject. She is also a journalist. This report is based on the proceedings of a national conference 'The Future of Race Relations Research' held in November 1988 at the University of Warwick, organised jointly by the Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations (CRER) and the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE). The conference was funded by the Commission for Racial Equality, with the additional help of a small grant from the Home Office. The conference was organised by John Wrench and Charlotte Wellington of CRER and Muhammad Anwar and Cathie Lloyd of the CRE. The report was written by John Wrench with the assistance of Evelyn Reid, who took notes throughout the proceedings and provided a transcript of the conference. Additional material was provided by Cathie Lloyd of the CRE and staff from the Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, in particular Harbhajan Brar, Harry Goulbourne, Mark Johnson, Daniele Joly, Sasha Josephides, Michael Keith and Mel Thompson. -

Guild of Students:Our History

University of Birmingham Guild of Students: Our History Contents Introduction 02 Introduction “This publication provides a captivating originally intended, to be the voice that “Think back to when you first experienced demonstrating against a rise in tuition fees 03 A Brief History account of the Guild’s history since its represents Birmingham students to the the Guild. We all have our own unique – we have all contributed to make the establishment in 1880. Over 130 years University and beyond.” story to tell - our own tale of what we did, Guild what it is today. old, the Guild of Students is steeped in how, when and where. That is the beauty 07 University of Birmingham Special Collections Guild of Students history and has changed significantly Andrew Vallance-Owen of the Guild - everyone has their own The ‘Guild of Students: Our History’ is a over the years. President of the University of Birmingham piece of its history. snapshot of what has been uncovered in 08 Democracy Guild of Students (1974/5) our archive, I hope you enjoy it.” Our History From my time as President in 1974/5, The Guild’s purpose is the same now as it has been fascinating to watch the Chair of the University of Birmingham it has always been – to make University Mark Harrop 11 Campaigns Guild flourish and grow, and witness the Guild of Students Trustee Board life for students at Birmingham that much President of the University of Birmingham development of the Students’ Union (2011 - present) better. Although the people may be Guild of Students (2011/12) 14 Student Groups The University of Birmingham Guild of Students (the Guild) into the Guild which exists today.