Competition in Public Transport (Hong Kong).Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of 674Th Meeting of the Rural and New Town Planning Committee Held at 2:30 P.M

TOWN PLANNING BOARD Minutes of 674th Meeting of the Rural and New Town Planning Committee held at 2:30 p.m. on 25.6.2021 Present Director of Planning Chairman Mr Ivan M.K. Chung Mr Stephen L.H. Liu Vice-chairman Mr Peter K.T. Yuen Mr Philip S.L. Kan Mr K.K. Cheung Dr C.H. Hau Dr Lawrence K.C. Li Miss Winnie W.M. Ng Mr L.T. Kwok Mr K.W. Leung Dr Jeanne C.Y. Ng Mr Ricky W.Y. Yu Dr Venus Y.H. Lun - 2 - Dr Conrad T.C. Wong Mr Y.S. Wong Chief Traffic Engineer/New Territories East, Transport Department Mr Ken K.K. Yip Chief Engineer (Works), Home Affairs Department Mr Gavin C.T. Tse Principal Environmental Protection Officer (Strategic Assessment), Environmental Protection Department Mr Stanley C.F. Lau Assistant Director/Regional 3, Lands Department Mr Alan K.L. Lo Deputy Director of Planning/District Secretary Miss Fiona S.Y. Lung In Attendance Assistant Director of Planning/Board Ms Lily Y.M. Yam Chief Town Planner/Town Planning Board Ms Caroline T.Y. Tang Town Planner/Town Planning Board Ms Denise M.S. Ho - 3 - Opening Remarks 1. The Chairman said that the meeting would be conducted with video conferencing arrangement. Agenda Item 1 Confirmation of the Draft Minutes of the 673rd RNTPC Meeting held on 11.6.2021 [Open Meeting] 2. The draft minutes of the 673rd RNTPC meeting held on 11.6.2021 were confirmed without amendments. Agenda Item 2 Matter Arising [Open Meeting] 3. The Secretary reported that there were no matters arising. -

Land Transportation Systems and Their Future,Mitsubishi Heavy

Land Transportation Systems and Their Future TAKASHI UNEDA JUNJI FURUYA NAOSHI NOGUCHI ICHIRO FUJITA YOICHI HIBINO sit systems and urban railroads. MHI is now developing 1. Introduction linear Shinkansen. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. (MHI) is develop- (1) Monorails ing guideway transportation systems, such as railroad Monorails are roughly classified into straddled and systems and new transit systems (transportation sys- suspended. MHI is manufacturing suspended mono- tems), for land transportation. MHI is also rails, which do not generate loud noise and can turn manufacturing products for road transportation such as sharply. Suspended monorails are unaffected by ad- toll collection and intelligent transport systems (ITS). verse weather conditions such as snow. MHI This paper gives an overview of transportation systems, suspended monorails are operating on the Shonan toll collection system and ITS technology, and their pros- Monorail and Chiba Urban Monorail (Fig. 11). pects. (2) New transit systems New transit systems use rubber tires that do not 2. Transportation systems generate loud noise and ensure high performance, 2.1 Overview making them suitable for automatic operation. In MHI has been manufacturing conventional railway Japan, MHI is now constructing new transit systems vehicles such as steam, diesel, and electric locomotives by providing vehicles, electrical power systems, and and rail motors and freight trains since early 1900s. MHI maintenance facility to Tokadai New Transit, has also been developing new transportation systems to Kanazawa Seaside Line, Kobe-Rokko Island Line, Port meet diversified transportation needs. The section that Island Line, Hiroshima Rapid Transit, and Tokyo follows details these transportation systems and their Waterfront New Transit “Yurikamome” (Fig. -

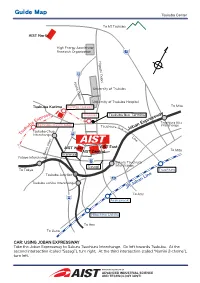

Guide Map Tsukuba AIST

Guide Map Tsukuba Center To Mt.Tsukuba AIST North High Energy Accelerator Research Organization 125 Higashi Odori 408 Nishii Odori University of Tsukuba University of Tsukuba Hospital Tsukuba Karima Kenkyu Gakuen To Mito Tsukuba Bus Terminal ess Tsukuba pr Ex a Tsuchiura Kita b Interchange u Bampaku Kinen Koen Tsuchiura k Ga u ku Joban Expressway s Tsukuba-Chuo en 408 T Interchange L in e AIST West AIST East To Mito AIST Central Sience Odori Inarimae Yatabe Interchange 354 Sakura Tsuchiura Sasagi Interchange To Tokyo Tsuchiura Tsukuba Junction 6 Tsukuba ushiku Interchange JR Joban Line To Ami 408 Arakawaoki Hitachino Ushiku To Ami To Ueno CAR: USING JOBAN EXPRESSWAY Take the Joban Expressway to Sakura Tsuchiura Interchange. Go left towards Tsukuba. At the second intersection (called “Sasagi”), turn right. At the third intersection (called “Namiki 2-chome”), turn left. Guide Map Tsukuba Center TRAIN: USING TSUKUBA EXRESS Take the express train from Akihabara (45 min) and get off at Tsukuba Station. Take exit A3. (1) Take the Kanto Tetsudo bus going to “Arakawaoki (West Entrance) via Namiki”, “South Loop-line via Tsukuba Uchu Center” or “Sakura New Town” from platform #4 at Tsukuba Bus Terminal. Get off at Namiki 2-chome. Walk for approximately 3 minutes to AIST Tsukuba Central. (2) Take a free AIST shuttle bus. Several NIMS shuttle buses go to AIST Tsukuba Central via NIMS and AIST Tsukuba East and you may take the buses at the same bus stop. Please note that the shuttle buses are small vehicles and they may not be able to carry all visitors. -

IIIIIIH 80525 Declaration

DECENTRALISATION IN HONG KONG: HOUSING, EMPLOYMENT AND LAND USE IMPLICATIONS by KULATILAKE, K. K.R.P. A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Urban Design The University of Hong Kong 8052,5 June, 2000 University of Moratuwa 805^5 IIIIIIH 80525 Declaration I declare that this dissertation represents my own work, except where due acknowledgement is made, and that it has not been previously included in a thesis, dissertation or report submitted to this University or to any other institution for a degree, diploma or other qualification. Signed: Kulatilake, K. K. R. P. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With a deep sense of gratitude I wish to acknowledge the following, whose most generous contributions in innumerable ways facilitated the realisation of this Study: • Prof. S. Ganesan, Course Director of the Master of Urban Design Programme and my supervisor of the study for his invaluable advice, intellectually vigorous discussions, guidance and encouragement given to me throughout the course of this study, • Prof. K.C. Lye, Chair Professor of the Department of Architecture, University of Hong Kong for spending his valuable time in giving his advice, invaluable comments and for imparting his wealth of knowledge at the initial stages of the study, • Dr. A. M. Ye and Mr. C.W. Ho, Assist. Professors and full-time lecturers of the Master of Urban Design Course, for their invaluable comments, suggestions and guidance given, • Prof. Willie Mendis, Senior Professor, Department of Town and Country Planning, University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka, for the kind advice and guidance given to me in my academic life, 4 • My dear colleagues of the Master of Urban Design Course for sharing their views and for being amicable with me all the time, • Messrs. -

Chapter 5: Getting Around Hong Kong

Chapter 5: Getting Around Hong Kong The Road Crossing Code It is safer to cross the road using footbridges, subways, “Zebra” crossings or “Green man” crossings. If you cannot find any such crossing facilities nearby, there are some basic steps for crossing roads that you need to observe: 1. Find a safe place where you can see clearly along the roads in all directions for any approaching traffic. 2. When checking traffic, stop a little way back from the kerb where you will be away from traffic. 3. Look all around for traffic and listen. However, electric/hybrid vehicles including motorcycles may operate very quietly. You need to look out for them in addition to listening. If traffic is coming, let it pass. Look all around and listen again. 4. Let the drivers know your intention to cross but do not expect a driver to slow down for you. 5. Do not cross unless you are certain there is plenty of time. Walk straight across the road when there is no traffic near. 6. Keep looking and listening for vehicles that come into sight or come near while you cross. 7. Do not carry out any other activities, such as eating, drinking, playing mobile games,using mobile phones, listening to any audio device or talking while crossing the road. Give all your attention to the traffic. Using crossing facilities Crossing aids are often provided to help you cross busy roads. Footbridges and subways: Footbridges, subways and elevated walkways are the safest places to cross busy roads as they keep pedestrians well away from the dangers of traffic. -

Asia-Express Logistics Holdings Limited 亞 洲 速 運 物 流 控 股 有 限

IMPORTANT If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this prospectus, you should obtain independent professional advice. Asia-express Logistics Holdings Limited 亞 洲 速運物 流 控 股 有 限 公 司 (incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) LISTING ON GEM OF THE STOCK EXCHANGE OF HONG KONG LIMITED BY WAY OF SHARE OFFER Number of Offer Shares : 120,000,000 Shares Number of Placing Shares : 108,000,000 Shares (subject to reallocation) Number of Public Offer Shares : 12,000,000 Shares (subject to reallocation) Offer Price : Not more than HK$0.58 per Offer Share and expected to be not less than HK$0.42 per Offer Share plus brokerage of 1%, Stock Exchange trading fee of 0.005% and SFC transaction levy of 0.0027% (payable in full on application, subject to refund on final pricing) Nominal value : HK$0.01 per Share Stock code : 8620 Sole Sponsor South China Capital Limited Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers China Tonghai Securities Limited Wealth Link Securities Limited South China Securities Limited Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this prospectus, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this prospectus. A copy of this prospectus, together with the documents specified in the section headed ‘‘Documents Delivered to the Registrar of Companies and Available for Inspection — Documents Delivered to the Registrar of Companies’’ in Appendix V to this prospectus, has been registered by the Registrar of Companies in Hong Kong as required by section 342C of the Companies (Winding Up and Miscellaneous Provisions) Ordinance (Chapter 32 of the Laws of Hong Kong). -

NWFB Route 792M Service Enhancement with Route 796 Series Service Adjustment Citybus Route 698R Cancellation

NWFB Route 792M Service Enhancement with Route 796 Series Service Adjustment Citybus Route 698R Cancellation (4 November 2014, Hong Kong) Effective 9 November (Sunday), service adjustment will be implemented on New World First Bus (“NWFB”) Route 796X, 796P and 796C. Effective 16 November (Sunday), NWFB will enhance the service of Route 792M, while service of Citybus Route 698R will be cancelled. Details are so follows: NWFB Route 792M Effective 16 November (Sunday), Tseung Kwan O bound service of NWFB Route 792M during 3:45pm to 5:45pm on Sunday and Public Holiday will be strengthened to 15 minutes headway, while the frequency at other service periods will remain unchanged. NWFB Route 796X Effective 9 November (Sunday), all departures to and from Lohas Park of NWFB Route 796X will operate via Le Prestige. New bus stops will be located at Wan Po Road before Shek Kok Road, outside Le Prestige and outside Tseung Kwan O MTR Depot for both bounds. Meanwhile, the routeing of departures during morning peak hour on Monday to Saturday operating between Tsim Sha Tsui (East) and Tseung Kwan O Station will remain unchanged. NWFB Route 796P Effective 10 November (Monday), departures of NWFB Route 796P at 7:20am and 8:05am will extend service to Silvercord Centre, same routeing as departure at 7:40am. New bus stops will be located at Salisbury Road outside New World Centre, Kowloon Park Drive outside No. 1 Peking Road and Canton Road outside Silvercord Centre, replacing the bus stop at Tsim Sha Tsui (Mody Road) bus terminus. NWFB Route 796C Effective 9 November (Sunday), So Uk bound service of NWFB Route 796C will divert after Nathan Road, via Cheung Sha Wan Road, Tonkin Street, and then resume its original routeing. -

Kowloon ¡V Canton Railway Corporation

STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT KEY ISSUES REPORT Hyder - Mott Connell Joint Venture This report is prepared by Hyder-Mott Connell Joint Venture for information and discussion purposes. The findings and recommendations do not necessarily represent the views of the HKSARG. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. INFLUENCING FACTORS AND KEY ISSUES 3. ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECTS AND KEY ISSUES 4. POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS REFERENCES ABBREVIATIONS 1 1. Introduction 1.1 Background 1.1.1 The HK2030: Planning Vision and Strategy (Main Study) is a strategic planning study tasked with preparing a strategic land use planning framework for Hong Kong for a period of 30 years. It will address ‘how much, what type and where land for development should be provided’. 1.1.2 The Government is committed to supporting and promoting sustainable development and to this end major policy and strategy initiatives must undergo a sustainability assessment. Under the overall goal of adhering to the principle of sustainable development, a planning objective of the HK2030 Study is to provide a good quality living environment. To achieve this, we need to strike a balance in the demand for, and supply of, environmental resources and a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is being undertaken as an integral part of the HK2030 Study. 1.1.3 To put the SEA into context, it is important to note that the Main Study involves four key stages of work viz: Stage 1: Agenda Setting, Baseline Review and Identification of Key Issues Stage 2: Examination of Key Issues Stage 3: Formulation and Evaluation of Scenarios and Options Stage 4: Formulation of Development Strategies and Response Plans 1.1.4 The SEA is being integrated with the Main Study by providing environmental input at all stages. -

District Profiles 地區概覽

Table 1: Selected Characteristics of District Council Districts, 2016 Highest Second Highest Third Highest Lowest 1. Population Sha Tin District Kwun Tong District Yuen Long District Islands District 659 794 648 541 614 178 156 801 2. Proportion of population of Chinese ethnicity (%) Wong Tai Sin District North District Kwun Tong District Wan Chai District 96.6 96.2 96.1 77.9 3. Proportion of never married population aged 15 and over (%) Central and Western Wan Chai District Wong Tai Sin District North District District 33.7 32.4 32.2 28.1 4. Median age Wan Chai District Wong Tai Sin District Sha Tin District Yuen Long District 44.9 44.6 44.2 42.1 5. Proportion of population aged 15 and over having attained post-secondary Central and Western Wan Chai District Eastern District Kwai Tsing District education (%) District 49.5 49.4 38.4 25.3 6. Proportion of persons attending full-time courses in educational Tuen Mun District Sham Shui Po District Tai Po District Yuen Long District institutions in Hong Kong with place of study in same district of residence 74.5 59.2 58.0 45.3 (1) (%) 7. Labour force participation rate (%) Wan Chai District Central and Western Sai Kung District North District District 67.4 65.5 62.8 58.1 8. Median monthly income from main employment of working population Central and Western Wan Chai District Sai Kung District Kwai Tsing District excluding unpaid family workers and foreign domestic helpers (HK$) District 20,800 20,000 18,000 14,000 9. -

Annual Report 2003 3

.33802 /15467 ,++- .33802 /15467 ,++- @^bYcedceWg[Z ^b g][ MWkaWb Pf`WbZf i^g] `^a^g[Z `^WX^`^gkA Kg] N`cceB R[i Vce`Z Uci[e EB EJ Sh[[b?f TcWZ M[bgeW`B Ocb\ Qcb\ U[`L @JHFA FEGE DFDE NWj L @JHFA FEGE DFEI iiiCbiY`CYcaC]_ a new way of living and working The New World Group has been active in the Mainland China property market since the early 1980s. New World China Land is helping to transform the nation and its people by offering a wide variety of property projects, encompassing residential communities, hotels, offices, shopping malls and resorts. We have always dedicated ourselves to delivering the highest quality developments. The Company is bringing new definitions of style and comfort, unprecedented levels of service and convenience. Together, these are creating distinctive environments for families or business. We stand for a whole new way of living and working. A truly national developer Global expertise Serving the community Our property portfolio spans Our professional management As we invest in a region, we the nation. By maintaining this team from Mainland China and recognise we have a broad geographic presence in from overseas brings together responsibility as a good Mainland China, we seek to diverse skills and expertise. We corporate citizen. We are play a key role in fulfilling the blend best international practice dedicated to improving the nation’s property needs. with home-grown vision and lives of the local communities talent to deliver unrivalled results. in which we operate. 30-year blue-chip heritage Best in class Turning dreams into reality Through our parent New World Quality is at the heart of We do more than build Development, a reputable and everything we do. -

English(PDF:4MB)

Living Guidebook for Foreign Citizens in Mito 2020 Mito City Table of Contents 1 Emergencies ………………………………………………………………………… 6 1-1 The words used when you are in danger………………………………………… 6 1-2 Sudden illness or injury and fire ……………………………………………… 6 1-3 Traffic accident or crime ………………………………………………………… 7 1-4 Disasters……………………………………………………………………………… 7 1-5 Information/Communication during disaster…………………………………… 9 2 Medical and Health Care ………………………………………………………… 11 2-1 Hospital/Clinic…………………………………………………………………… 11 2-2 Illness or injury on holidays or at night………………………………… 12 2-3 Medical Insurance………………………………………………………………… 13 2-4 Health check-up, cancer screening, etc.…………………………………… 14 3 Resident Registration, etc. …………………………………………………… 15 3-1 Residence Card …………………………………………………………………… 15 3-2 Resident record…………………………………………………………………… 16 3-3 Registered seal and Certificate of Seal Registration…………………… 19 4 Taxes ………………………………………………………………………………… 21 4-1 Income tax ………………………………………………………………………… 21 4-2 Resident tax ……………………………………………………………………… 21 4-3 Consumption tax…………………………………………………………………… 22 4-4 Vehicle Tax / Light Vehicle Tax……………………………………………… 23 4-5 Property tax / Urban planning tax…………………………………………… 24 5 Pregnancy/Childbirth and Child-rearing …………………………………… 25 5-1 When you have become pregnant………………………………………………… 25 5-2 During pregnancy ………………………………………………………………… 25 5-3 When you have given birth……………………………………………………… 27 5-4 Child-rearing……………………………………………………………………… 29 6 Education …………………………………………………………………………… 35 6-1 Elementary School and Junior High School ………………………………… -

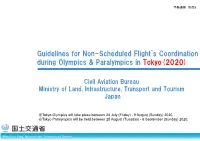

Guidelines for Non-Scheduled Flight`S Coordination During Olympics & Paralympics in Tokyo(2020)

事務連絡 別添3 Guidelines for Non-Scheduled Flight`s Coordination during Olympics & Paralympics in Tokyo(2020) Civil Aviation Bureau Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Japan ※Tokyo Olympics will take place between 24 July (Friday) - 9 August (Sunday) 2020, ※Tokyo Paralympics will be held between 25 August (Tuesday) - 6 September (Sunday) 2020. Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism 1. Summary for Non-Scheduled Flight`s Coordination in 2020S ・Six airports below are temporarily treated as “Level 3 Airport” during Jul-Sep 2020. ・“Special Coordination Period” is set during Dec2019 -Feb2020 in order to coordinate non-scheduled flights flying in “Demand Concentrated Period (17Jul–13 Sep)”. ・For earlier treatment, “Pre-Special Coordination Period” opens for SDJ and NGO during Aug-Sep 2019. 2020 Airport Name Special Note 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 S19 W19 S20 W20 Historic (9/9) Agreed Historic (9/26) Initial Submission SAL (10/3) Slot Conference (10/31) Slot Return Deadline (11/12-15) (12/15) (3/29) Start of Season Narita (NRT) Early Early Demand Official Point of Coordin S20 Coordin Concentrated S20 Entry and Departure ation ation Period Haneda (HND) (7/17 - 9/13) Ibaraki (IBR) Civil/Self Defence Force Special Coordination Period (Dec to Chitose (CTS) End-Jan) Official Point of Ad-Hoc Entry and Departure Coordination Sendai (SDJ) Pre-Special Coordination Period (early Aug to Chubu (NGO) late Sep) 1 2-1. Temporary Change of Level (Outline) Airport Name IATA Code Airport Level Airport Name IATA Code Airport Level New Chitose CTS 2→3 New Chitose CTS 2 Sendai SDJ 1→3 Narita NRT 3 According to WSG 6.6 (Temporary Narita NRT 3 Haneda HND 3 Change of Level), three new airports Haneda HND 3 Chubu NGO 2 will be temporarily designated as → Kansai KIX 2 Level 3 in 2020S.